When easterners speak of “frost on the pumpkin” to describe their fall season, Northern California anglers may find it hard to relate. Our fall season usually finds us sizzling on the Sacramento, marinating on the McCloud or parboiling on the Pit. Fall usually swelters in Northern California until, usually some time in October, the mercury dips back into a comfortable range. These seasonal changes trigger age-old natural cycles in the rivers, one last smorgasbord for the fish before the long, wet winter sets in.

Northern California has a number of rivers boasting great fall hatches, notably the upper Sacramento, McCloud, Pit, and Trinity. The lower Sac and the Trinity also swell with the return of salmon and steelhead filling the water with their eggs, a treat few fish can pass up. Amazingly, the angling on every one of these rivers is as good or better than it was 25 years ago. With California’s current population nipping at 40 million, that’s remarkable. This is no happy accident, either. While looking at our terrific fall fishing opportunities, it’s also good to reflect on how they came to be.

Something Different and Fun

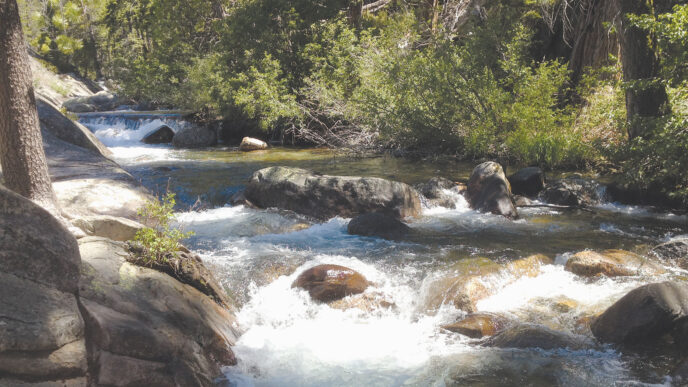

It doesn’t get much better than October Caddis season. It’s still warm, the sky is typically blue, and the leaves have begun blushing yellow and orange. Where there is an abundance of food, especially large food, even usually reserved trout come undone. Great destinations for this hatch include the upper Sac, the McCloud, and sections of the Pit River.

You could choose to fish the October Caddis hatch in the same nymph-under-an-indicator way that most trout are caught in this part of the world. But why not step out of the norm and do something different, like brandishing a big, ungainly dry fly when you can? Opportunities for splashy dry-fly fishing aren’t nearly plentiful enough, so I seek a particular water type for the most excitement possible.

The best places have a moderate current and are at least two to three feet deep, filtering through a garden of exposed rocks. I usually save this fishing for evenings, the height of the October Caddis egg-laying soiree, fishing nymphs instead during the hours of high sunlight. It pays to scout these boulder-strewn sections in advance, rather than waste good fishing time in the fading light searching for the right water.

Someone dubbed this kind of fishing “picking pockets” with big, bushy dry flies, and that’s how I’ve always thought of it. The idea is to slap your dry fly on the water around boulders, in pockets, and near undercut banks and seams. This is not blindly fishing the water. It’s strategically identifying places where there ought to be a trout and concentrating on just those spots. Forget about finesse and focus on dropping your fly on target. If you can get close enough to keep all your line off the water, so much the better. All you need is a few feet or a few seconds of reasonably good drift before the fly is either eaten or whisked away.

Move frequently. When casting to a likely spot, don’t insult the fish by making a hundred casts to the same place. If you’re getting a good drift with a decent imitation, the fish will likely strike on the first few casts or not at all. Only brain-damaged fish would hit a fly after refusing it 25 times. I will admit there are a few such fish in every stream, but don’t rely on that.

There are lots of big, bushy October Caddis imitations perfect for this work. General attractor patterns do the job well enough, such as a Stimulator or Madam X, size 8. There are also hatch-specific patterns such as Ken Morrish’s Adult October Caddis and Mercer’s Skating October Caddis. If you’re fishing the kind of place where a fish is forced to be quick or be hungry, almost any large, buoyant dry fly will do.

Though droppers are usually associated with nymph fishing, you can fish two big dry flies quite easily with this technique. The trick is to use monofilament (or fluorocarbon) stiff enough to resist twisting and tangling while fishing a short line. You can get away with a slightly shorter, heavier leader, too. Keep your leader to about 7-1/2 feet, tapering to 4X. Fluorocarbon is not as buoyant as mono, but in this case, it works just fine. Your flies won’t be on the water long enough for lack of buoyancy to be a hindrance.

I usually tie a foot or two of 4X fluorocarbon to the bend of the top hook and attach the dropper fly with a Clinch Knot. Every couple of casts, lift your flies off the water and let them hang for a second to give twists a chance to work themselves out. It also helps to dress your flies frequently with a powdered desiccant to keep them floating high and dry.

The Upper Sacramento

The upper Sac has the most prolific October Caddis hatch I’ve ever seen. Of course, things change from year to year and even from day to day. Some evenings, the hatch is fantastic; other nights, it’s abysmal. When it’s on, there are big, fluttery wings thrumming the air, bugs riding the current to the delight of the fish, and legs crawling on your neck and face in the fading light. It can be spectacular.

The higher you go on the river, the better the October Caddis hatch is likely to be. Think Dunsmuir and above, where you can focus on the abundant pocket water with dry flies. Some of my best evenings have been around the Cantara Bridge, which is an irony, because it was from this spot that death once crept downstream all the way to Shasta Lake.

Where were you when the railroad car went off the Cantara Bridge on July 14, 1991? I was sleeping soundly in my Redding home, oblivious to what was happening until the next morning. That night, when the tanker car derailed, it spilled roughly 19,000 gallons of a herbicide called metam sodium into the river. Sternly warned to stay away from the area, I spent the rest of that day on the phone, getting and giving information about the disaster. The river was closed, and so was Interstate 5 for a while, as the poison worked its way downstream, killing every plant, bug, and fish in its path. The river reopened to angling in 1994, and the fishing was epic.

The saga of the river’s recovery is too long to cover here, but there is a happy ending. Though scant records of the trout population were kept prior to the spill, the staggering number of fish carcasses suggested the river was much more capable of sustaining wild fish than anyone had thought. As a result, the emphasis in managing the river shifted from a put-and-take, hatchery-fish mentality to creating a wild trout, self-sustaining fishery.

Mac Attack

While its hatch is not quite as dense as the upper Sacramento’s, the McCloud has a great October Caddis hatch, as well. The Mac also has something that the upper Sac wishes it did — a healthy population of big, nasty, hook-jawed, carnivorous, streamer-menacing brown trout. You can fish the McCloud anywhere from the dam down through the Nature Conservancy water, but getting a reservation on the Conservancy in October for one of the five reserved spots can be tricky. If you want to try, phone (415) 777-0487. Luckily, there are five first-come walk-on spots, as well, and the public water between the dam and Conservancy is also excellent. If you want to fish the October Caddis hatch here, look for the same pocket water as on the upper Sac. There’s a lot of it.

If you choose to target the big browns, focus on the deep pools and plan on fishing when the sun is off the water. This is a great opportunity to do something a little different and fish a streamer with that sink-tip line that collects dust most of the year. Quarter your casts up-stream, giving the tip a chance to sink, and mend as necessary. When you think your fly is deep enough, start stripping line. I usually fish it strip-strip-strip-pause, strip-strip-strip-pause. Make sure you bring your fly all the way back to the rod tip. For reasons known only to brown trout, they often grab the streamer just as you’re about to recast. When I fish this way, I’m actually less concerned about landing fish than I am about getting that big grab. The strike of a big brown on a streamer is not unlike an electric shock, but without the pain. The fish was attempting to kill its prey, not eat it, yet.

When fishing for fall browns, almost any reasonable streamer will do. Brown trout are killers by nature, which is why we love them. I prefer smaller streamers, size 6 to 8, and often fish Woolly Buggers, leech patterns, and Muddler Minnows. McCloud River browns spend part of the year in Shasta Lake eating threadfin shad, so shad imitations are also worth throwing. Part of the fun is experimenting with flies and retrieves until you find what works. Don’t expect to catch as many trout this way, but what you do land likely won’t be small. Fish a short leader, such as a 5-to-6-foot section of 1X. If you haven’t spent much time streamer fishing, you need to understand that it is perfectly normal to miss strikes. You won’t miss them all.

As I write this, the dam on the McCloud is in the midst of the relicensing process. Indications are that there will probably be more water in the river in the future, at least for some of the year, just as has happened on the Pit. Of the rivers discussed here, the Mac has probably changed the least in 25 years. Special angling regulations, private ownership limiting the number of rods, and

the river’s general remoteness have done a credible job of protecting the fishery. More water is always good for fish, and what’s good for the fish is good for anglers, as well.

Not the Pits

Speaking of more water, as a requirement of its renewed license for the Pit 3, 4 and 5 Hydroelectric Project, PG&E increased its minimum flows in the Pit River, and as a result the river is producing larger fish than ever before. The downside is that it is more difficult to wade than it once was, and it never was easy. The higher, faster water in recent years means anglers have to be that much more careful when wading. Places in the stream that were possible to fish years ago are simply beyond the ability of many waders today. It’s a two-sided coin, really.

The additional water creates more and better habitat for the fish while also making it more difficult to get at those fish. Nevertheless, the fishing continues to get better for those willing to try.

In saying there is great October Caddis fishing on “sections” of the Pit River, I’ve said enough. They are in certain parts of Pit 3, but you need to hunt for them.

The Pit has Isonychias in the fall, as well. The Isonychia mayfly nymph is a strong swimmer, but you rarely ever see them. Most anglers seem oblivious to this fall hatch because most of the activity happens in the dark. Like stoneflies, the Isonychia nymphs swim to rocks to emerge, but the fish often focus on swimming nymphs during daylight hours.

The Pit is short-line nymphing headquarters, and you fish Isonychias the same way you would normally fish the Pit, but with one caveat. During Isonychia season, pay particular attention to letting your nymph(s) swing to the surface at the end of each drift. That motion is often the trigger that induces a trout to grab your fly.

When I hear people moaning about how hard the Pit is to wade with the additional water, I politely remind them they should be thankful for what they have. Prior to 1980, there was no water — zero, zip, nada — in Pit 3. It’s thanks to CalTrout that we have a fishery there at all, and now the fish are getting bigger.

The Lower Sacramento

Because of its size, the lower Sac is most efficiently fished from a drift boat. But that doesn’t mean you can’t do very well indeed on foot. During the fall, the water level is at about a third of summer’s flows, and wading opportunities abound. That said, please wade with great caution. Do not wade on or around salmon redds. The redds are usually pretty obvious as cleared depressions in the streambed, and there are often salmon churning up the water in the vicinity. Toss an egg pattern in behind the redds, and you may be rewarded by the squadron of rainbows waiting there for an omelet. Leaders tapered to 3X or 4X fluorocarbon work well, and I think a Loop Knot beats a Clinch Knot for this fishing any day.

Few people would acknowledge 1997 as a banner year for the lower Sac fishery, but that was the year the temperature control device (TCD) added to Shasta Dam began operation. The Bureau of Reclamation had found itself in conflict with the Endangered Species Act as salmon populations in the Sacramento River continued a downward spiral, so it was forced to act. Prior to when the TCD came online, providing water in the temperature range best for salmon (and trout) meant bypassing the dam’s power plant and missing out on producing much needed electricity. This placed fish and hydroelectric power in an adversarial, eitheror relationship. The TCD ended this, and the flows through and below Redding have been much cooler ever since, with no loss of power. Before the TCD was installed, good trout habitat extended down to about Anderson. Since 1997, the cooler water has created more trout habitat by extending it downstream all the way to Red Bluff.

The Trinity

The Trinity River is among California’s richest steelhead fisheries, and it has only gotten better over the years. Like a lot of people, I caught my first steelhead on the Trinity. In those days, most of the fish were hatchery steelhead. Today, wild fish continue to gain ground, and anglers report that about half the fish they catch are wild.

I’m aware of how dumb this sounds, but Trinity River steelhead can act just like big rainbow trout. What I mean is, sometimes it seems as if they’ve forgotten they’ve ever been to the ocean at all. They will take dead-drifted egg patterns under a strike indicator or steelhead flies on the swing, but they will also take almost any well-drifted trout nymph. You don’t normally think of steelhead as being suckers for a size 14 Pheasant Tail Nymph, but it happens on the Trinity. They will even take dry flies.

There is one notable difference between Trinity steelhead and big rainbow trout. Steelhead don’t stay in one spot or area, the way resident trout often do. In other words, you can have a great day fishing in a particular spot, return a few days later, and the fish will be gone. Steelhead are fish on a mission, and unless you find them sitting on a redd (where you shouldn’t bother them anyway), they have other priorities.

Trinity River fish are accommodating, but not stupid. You can use almost any approach you want, from egg patterns, to nymphs, to steelhead flies, to even, yep, October Caddis dry flies. Like most trout, they won’t settle for a subpar presentation. The river is easily waded, and there is an awful lot of Trinity River to fish, despite its popularity.

Of all the rivers mentioned here, the Trinity has required the most restoration work. The fishery continues a solid recovery from past abuses, mainly dredging, dam building, and diverting most of its water south into the Sacramento River. Some of the flows have been restored to the river. Channels have been rebuilt, spawning gravel added, and sediment better controlled. More work is needed, but the strength of the wild steelhead recovery so far suggests we are on the right track.

Get out there and enjoy some great fall fishing. “Frost on the pumpkin” may describe autumn in the East, but in Northern California, “Bend in the fly rod” is more like it. These great fisheries host terrific fall fishing opportunities, and in one way or another, all have benefitted recently or will benefit from improvements that help restore these fisheries. Tip your hat to all the terrific people and groups who made this happen and who continue to make it all possible.