Asother boats were drifting downstream toward a hot dinner, a nightcap, and a soft bed, we were running upstream in the waning light, trying to dodge the majority of boulders hidden under the glare of a quicksilver surface. The daytime fishing had been relegated to drifting shiny little nymphs under bobicators. Bugs were barely hatching during the day, and those that did failed to bring trout to the surface. The few fish we did catch were obese, their bellies filled with mushy bug parts, including wings. Lots of wings. My guess was that something was hatching just at nightfall or at daybreak, and since the boat ramp was operating on banker’s hours, our only recourse was to tie up to a tree and sleep in the boat if we were to intercept the hatch. As darkness enveloped the canyon, not a single insect came off the water, nor did a single fish rise. Except for the distant hum of hydroelectric turbines from the dam upstream, the night air was uncharacteristically silent. We admitted defeat, wrapped ourselves in sleeping bags, and nodded off.

At around midnight, I awoke with a start. Apparently, the dam operators were releasing a large pulse of water, for the river had gone from calm to roaring. On top of that, spiders were crawling all over my face. Blindly groping around the bottom of the boat, I finally fingered the mega flashlight that turned blackness into day.

The spiders on my face turned out to be not spiders at all, but hundreds of moths. The roaring of the river wasn’t caused by rising waters, but by rising trout. The fish were not sipping or gulping, but detonating through the river’s surface. As far as the flashlight’s beam could carry through the snowstorm of pale moths, the river was frothing with trout. I have never, ever witnessed such a spectacle.

Aquatic moths share a very similar lifecycle with caddisflies. The larvae live and feed underwater, then they pupate. The adult moths hatch and rise quickly to the surface, then immediately fly off the water. Trout feeding on moths need to react rapidly to chase down the ascending bug, and the resulting rises are explosive.

This spectacle occurred because we were fishing a tailwater. To support such a density of insects (and trout), a river has to be exceedingly rich, cool, and protected from the extremes of both scouring flows and drought. In the vast majority of cases in the West, this Goldilocks water is created in reservoirs and discharged as tailwaters. Reservoirs not only collect water, they collect dead things, such as leaves, trees, raccoons, fish, and birds. The nutrient from these decaying dead things feeds algae, microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, and benthic macroinvertebrates such as mayflies, midges, and shrimp. As water stalls behind the dam, it entrains minerals from the bottom of the lake, and evaporation causes the broth to concentrate and grow richer and more productive. The temperature of the tailwater is extremely important to downstream fish. Water that comes off the top of a reservoir can be so warm it will kill trout and salmon downstream. In some reservoirs, water is pulled from various strata in mixing towers and released at precise temperatures. A case in point is Shasta Dam on the Sacramento River. Chinook salmon running up the Sacramento to spawn used to swim into a wall of warm water released off the top of Shasta and stop their upstream migration. They would wait for cooler waters, and in the interim, many died. Of those that survived, many of their eggs were infertile from cooking in the warm water. Through the power of the Endangered Species Act, Shasta was retrofitted with a system that could draw water from any level in the lake, and the effort paid off, with the Sacramento River being kept at an optimal salmonid temperature range in the low-to-mid-50s. Not only did salmon respond positively, but a good trout fishery was transformed into a fantastic trout fishery that draws visitors from around the country.

Tailwaters tend to be clean, because suspended material precipitates out of the water while it sits behind a dam. This can be good for aquatic plant growth, but the same process that cleanses the water of suspended sediment also prevents gravel and woody debris (logs and branches) from migrating downstream. Gravel is necessary for spawning and as habitat for smaller organisms. Woody debris is a critical component for structure, habitat, and the liberation of nutrients bound in the wood. Gravel and woody debris are so valuable to a river system that in many places, they are artificially introduced below dams.

A special bonus for anglers plying tailwaters that sit downstream of hydroelectric projects is the opportunity to fish with flesh flies. In many waters, small fish such as smelt are sucked into the headrace, chopped up or stunned by turbines in the electric generators, and then flushed out in the tailrace. Some of the largest trout on record have been caught on flies and lures imitating injured or maimed baitfish in the tailwaters immediately below hydroelectric stations. California has many such facilities, and they are largely overlooked by most anglers.

Dams have universally been given a bad rap by conservationists. Some dams have had their day as a functional tool, but are resting on their laurels and should be removed. Other dams are much worse than useless and shouldn’t have ever been built. And there are dams that clearly ben-efit society beyond their environmental cost, and that benefit should be recognized.

Three dams in my backyard on the Yuba River are perfect representations of the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The Daguerre Point Dam upstream from Marysville is the ugly one. It was built to capture debris released by hydraulic mining during the Gold Rush. It performed its intended purpose so well that today, it is filled to the brim and overflowing with gravel. It has no capacity as a reservoir and has been repurposed to shunt water to farms, but using a 26-foot-tall dam to divert water into a couple of irrigation ditches is like killing a fly with a rocket-propelled grenade. The same ditch-water diversion can be done with minimal impact on the river. Daguerre Point Dam is completely blocking upstream passage for endangered sturgeon, and its flawed fish ladders are a major impediment to migrating steelhead and salmon.

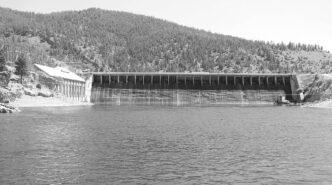

The next dam upriver is Englebright. Englebright Dam was funded in the 1880s to stop mining debris from inundating Sacramento. After it was funded, hydraulic mining was outlawed, and the debris flow dramatically slowed. During the Great Depression, some fifty years later, government types discovered that a forgotten cache of money had been set aside to build a dam. With no other purpose than to create jobs, a 260-foot-tall dam was built across the Yuba River that totally blocked salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon from forty miles of spawning habitat. It traps 100 percent of the gravel and woody debris that are necessary for downstream spawning and habitat. Today, Englebright Reservoir has zero flood-control capacity, zero irrigation capacity, and only belatedly has been retrofitted with a minor hydroelectric facility. This is a bad dam that should have never been built, and no one with a straight face can argue its merits. Yet it stands.

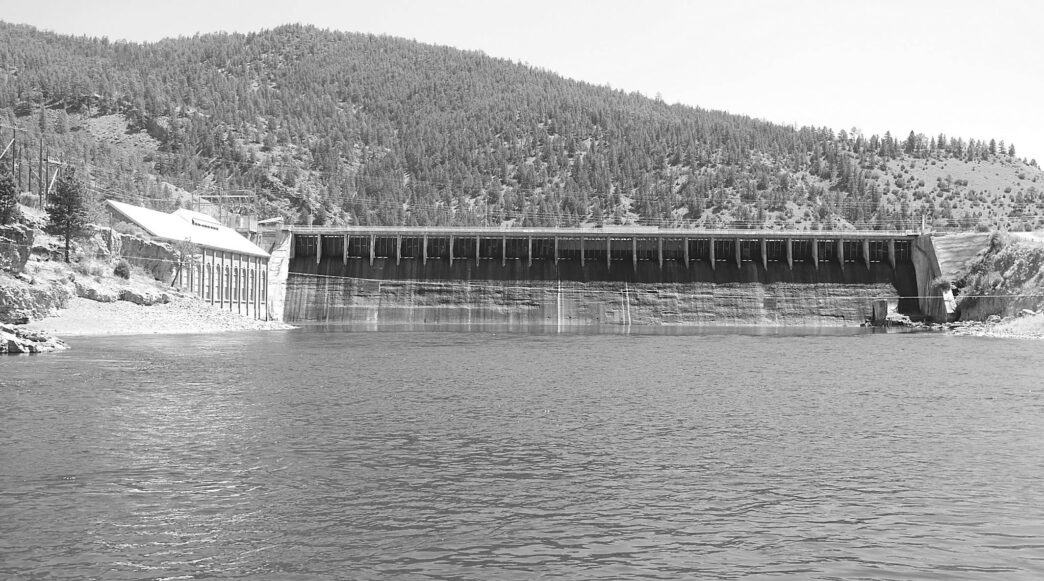

The New Bullards Bar Dam is a massive structure on the North Fork of the Yuba. It provides major flood control for the entire Sacramento Valley region, provides much-needed irrigation for California’s crops, and produces copious amounts of “green” electricity. That’s good. New Bullards Bar has the largest Pelton wheels in the world and produces a staggering 315 megawatt of electricity on demand. This dam, at 635 feet, has wrought undisputed environmental havoc, yet its costs are worth the benefits. Dams come with a price tag. I’d rather see a wild-flowing river than a dam with an artificially created great fishery, but like any good hypocrite, I’ll never pass up a chance to cast a fly into a tailwater.