The tumbling stretch of pocket water that I found myself on late in the afternoon begged to be fished with any one of several different methods. Should I tie on a dry fly and fish on top? That splashy rise to the dry is so cool. Should I try a Czech nymphing rig and roll the bottom in hopes of hooking a bigger fish? How about an indicator rig, or maybe even a streamer?

Wait a second, what about those little wet flies I tied last year? A quick inventory of the rear pocket of my vest soon turned up a small aluminum box with its wet flies neatly lined up in the clips. I quickly changed my leader and chose two old favorites, tying a size 16 Greenwell’s Glory at the bottom position of a two-fly wet-fly rig, with a lightly weighted Western Coachman in size 12 as the dropper.

I extended a few feet of line off the tip of my rod and allowed the leader and flies to straighten in the current below me. A seven-inch rainbow immediately snatched the Greenwell’s Glory and thrashed about on the surface for a few moments until I could carefully slip the barbless hook from its jaw. Then I picked my way downstream through the pocket water, swimming and dancing my flies with gentle mends and rod-tip manipulations. The fish weren’t big, but their willingness to attack my wet-fly rig made the afternoon an enjoyable one, filled with tugs, slashes, and out-and-out misses.

As the pocket water gave way to the top end of a deeper pool, I decided to try something a little different and added a couple of feet of tippet to the end of my leader, stretching its length from 10 feet to 12 feet.

I left the Western Coachman in the bottom position and tied on a heavily weighted and heavily dressed black Woolly Worm with a red marabou tail and a grizzly hackle as the dropper. I cast up and across the stream using a reach cast that, combined with an immediate mend, allowed my two-fly rig to sink for the first 10 feet of its drift. As I tightened the line, there was a sharp, heavy pull, and soon, almost two feet of crimson-striped rainbow trout was in the air, the Woolly Worm securely pinned in the corner of its jaw. As I released the fish, I pledged to myself to spend more time fishing wet flies.

A Simple Two-Fly Wet-Fly Cast

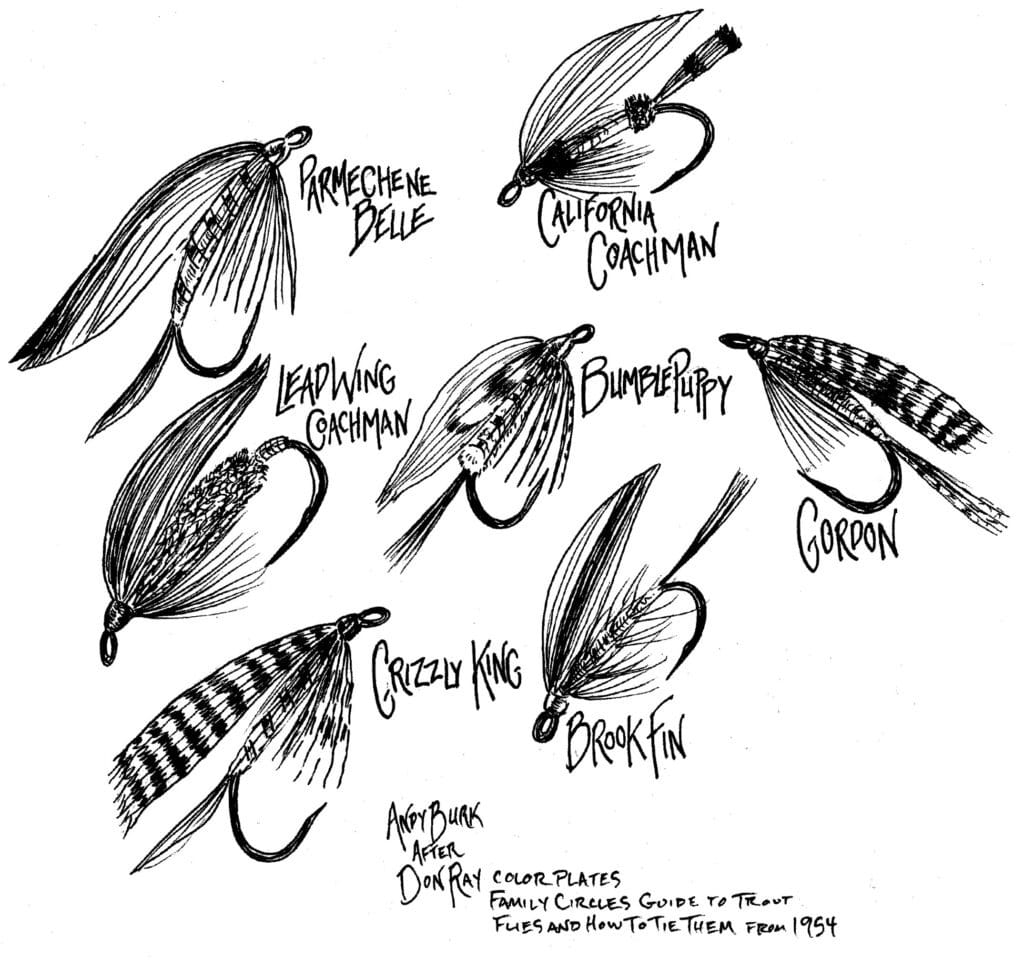

Swinging wet flies on multiple-fly rigs used to be the default angling method for American fly fishers from the nineteenth century well into the twentieth. The ratio of wet flies to dry flies in the fly plates illustrating Ray Bergman’s Trout, first published in 1938, for example, was close to three to one. The traditional wet-fly rig, or “cast,” consisted of a fly at the end of the leader with droppers at different intervals above it, with a three-fly cast being the norm. This allows different flies to be presented at different depths.

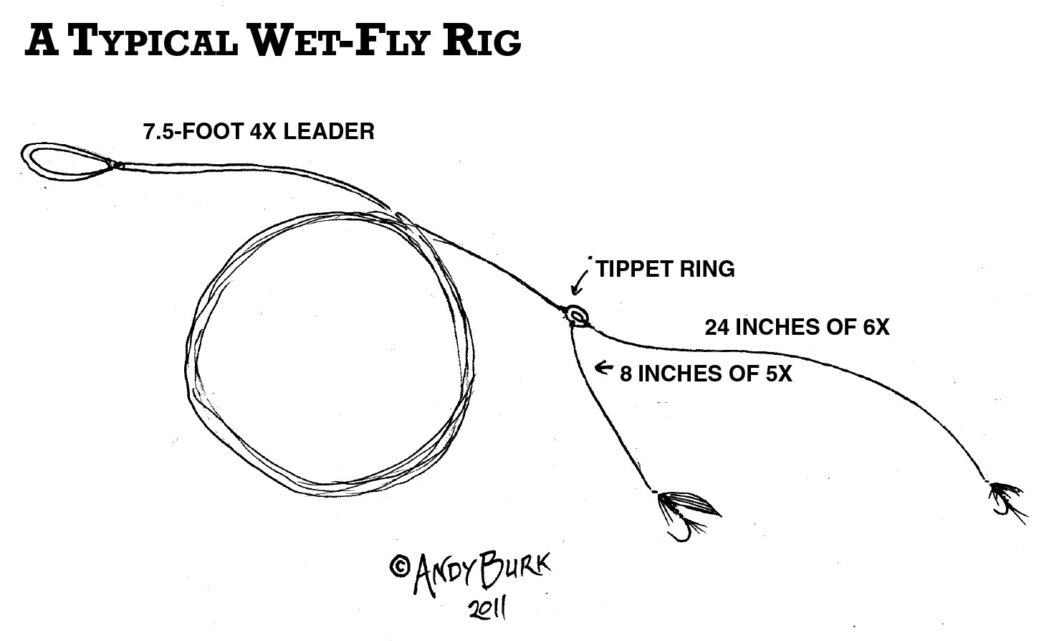

I like to keep my wet-fly rigging simple, using two flies instead of the traditional, old-school rig of three. I find that the best way to start is with a standard 71/2-foot leader tapered to 3X or 4X. To the tip of this leader I affix a small tippet ring. The tippet ring allows me to tie on a dropper tippet quickly and easily. To this ring, I add 8 to 12 inches of 4X or 5X dropper tippet, then 24 to 36 inches of 5X or 6X main tippet. If you’re more of a traditionalist, forego the ring and create the droppers using knots along the leader.

Some of the wet-fly fans who I know build their own leaders from butt to tip, complete with dropper or droppers, and carefully coil them on plastic or cardboard cards. I usually wrap my wet-fly leaders around a Tackle Buddy, which I think was originally designed for bait rigs and the like. At any rate, it’s a handy way to store pretied wet-fly leaders and rigs.

As with all multiple-fly riggings, adding more flies and knots to any rig usually invites more potential tangles. The best tip I can give you to reduce tangles is to make sure that anytime you are not fishing, the bottom fly is in the hook keeper and the top fly is either hooked in the frame of a guide or stuck in the cork of your rod grip. When moving through brushy streamside areas, I find it best to go more slowly than normal and to go in rodtip first, carefully steering around obstructions. That said, I am probably the guy you hear cussing upstream as I’m hung up in the willows from carelessly charging along the shoreline.

The Flies to Use

There are literally thousands of wet-fly designs, but there are not exactly thousands of wet flies available in your normal fly shop. Still, you’ll usually be able to buy a variety of soft hackles. They’ll work great, and you need plenty of them in your fly box. But in today’s angling world, a Greenwell’s Glory, Cowdung, Leadwing Coachman, Peter Ross, or Silver Invicta will be a bit harder to come across. I’m sure there are plenty of resources for wet flies available via the Web, and of course, you could always tie your own.

If you tie flies, you’ll find that tying wet flies is enjoyable, and for the most part they’re not too hard to tie. I usually prowl around UK-based websites to find different and unusual wets to try. I also create a lot of different wet flies based on the insect life in my home waters. Every bug that hatches from the stream comes back to the stream to lay eggs and die. The ones that don’t get eaten on the surface drown and may be found in all levels of the water column, and many caddises and Baetis mayflies crawl back underwater to lay their eggs. Using appropriate hatch-matching wet flies can be one of the most rewarding facets of wet-fly fishing. It’s easy to tie wet versions of all your dry favorites just by changing to softer, more absorbent materials that are suited for subsurface designs.

My Favorite Wet-Fly Tactics

The traditional wet-fly angling method is to swing the flies with a more or less down-and-across cast, mending line upstream to sink them deeper and slow them down or downstream to speed up their swing. Most of the time when I am fishing wet flies, I fish them downstream. It allows me to cover all of the fishy water easily. I love fishing wets in pocket water with short casts — somewhere between 10 and 20 feet. By fishing a short line, I can easily control exactly where my flies are swimming, making sure that they dangle, drift, and swim through likely trout-holding zones.

The wet-fly method will work in all areas of the stream, though, from pocket water to riffles and pools. This method maximizes the time your flies are in the water, which is after all where the fish are. You’re always swimming, dangling, and leading your flies, and your fishing begins the second your flies hit the water.

Wet Flies in Pocket Water

We’ll start fishing a two-fly rig in your favorite piece of pocket water with a Western Coachman on top and a small caddis wet on the bottom. Start by making short, slightly downstream casts to the water right in front of you, letting the pair of flies come under tension and then steering them with an elevated rod tip into likely holding zones. Smaller pockets may require only one or two casts. The smaller the pocket, the fewer casts will be required to fish it. Don’t skip any spots in the pocket-water environment, though. Every rock, depression, and tailout can have willing trout. You can fish wet flies in pocket water at any time of the day, but I’ve found late afternoon to early evening to be the prime time for wets in pocket water.

Wet Flies in Riffles

Riffles and runs are two places where the wet-fly really comes into its own. Before, during, and after major hatches, the well-prepared wet-fly angler can have a field day. The biggest benefit of fishing wet flies in riffles is the amount of water that can be covered. By casting slightly across and downstream, starting with short casts and ending with long, riffle-sweeping casts that cover huge amounts of holding water, I move quickly through riffles, looking for “players,” fish that are motivated enough to chase a swimming fly.

When fishing riffles, I usually try to do a minimum of mending. Usually, a reach cast, followed with a gentle upstream mend, is all that is required. I like to let the river fish the fly for me. It always seems to take the fly where the fish are. Use a slightly elevated rod tip to help pull and lead your flies through likely spots.

The Wet Fly in Pools

Wet flies can be extremely effective when fished in pools and even in the slow-er-moving “frog water” in a stream. If you want to increase the effectiveness of your wet-fly game in the pool environment, you’ll need to invest in a couple of sinking leaders. I use these in 7-1/2-foot and 12-foot lengths, depending on pool depth. I like fast-sink-rate leaders, and I rig them with a tippet ring and a 2- to 3-foot tippet of 4X or 5X mono. I usually tie a 8-to-10-inch dropper of 3X or 4X to the tippet ring. When fishing pools, I like to use a larger wet-fly — usually a Woolly Bugger, Aggravator, or some other meaty bug as the dropper fly and a smaller imitative wet on the bottom. Pick something that matches the prevalent hatches on the water you’re fishing and you’ll have a deadly combination for dredging for trout in deep water.

The pool environment will require you to swing the flies very slowly and to retrieve them, as well. With each cast, you will be animating your flies. I like to use slow, twitching retrieves that make my flies look like struggling, drowning insects.

This tactic is also great to use in those swirly, toilet-bowl eddies that often can be so frustrating. I like to slop a cast into these areas and let the river swirl it around, holding my rod tip low and imparting subtle twitches and pauses during my retrieve. Strikes usually come as sharp pulls, and a quick tug with your line hand will put the hook home.

We’ve just scratched the surface of a few of the cooler aspects of wet-fly fishing. Don’t be afraid to experiment! I fish wet flies in all kinds of different water types with success. If you get into the world of the wets, there are centuries of history and thousands of productive patterns. Do a little research, and you’ll soon find yourself hooked by wet flies. Tie on a pair of wets and go fishing!