I have a fly pattern that is probably as good as any in your box, if not better. It is better than most patterns you will find in a fly shop, fishing catalog, or on a Web site. It works just about anywhere, anytime. It might as well be called a magic fly, because some of its key properties are invisible.

Am I trying to sell you the “latest and greatest” pattern so that I might part you and your wallet from a wad of hard-earned cash? The answer is decidedly no. I couldn’t sell this pattern if I tried. I haven’t even bothered submitting it to Umpqua Feather Merchants, with whom I’ve been a contract fly designer for decades. From long experience, I know that fly shops, catalogs, fishing magazines, Web sites, and fly wholesalers couldn’t give a rip if a fly is simply effective. They want a fly with “bin appeal.” They want a fly that jumps out of the display case into the customer’s hand and gets processed through the cash register. A fly that doesn’t sell itself might as well be a lump of coal.

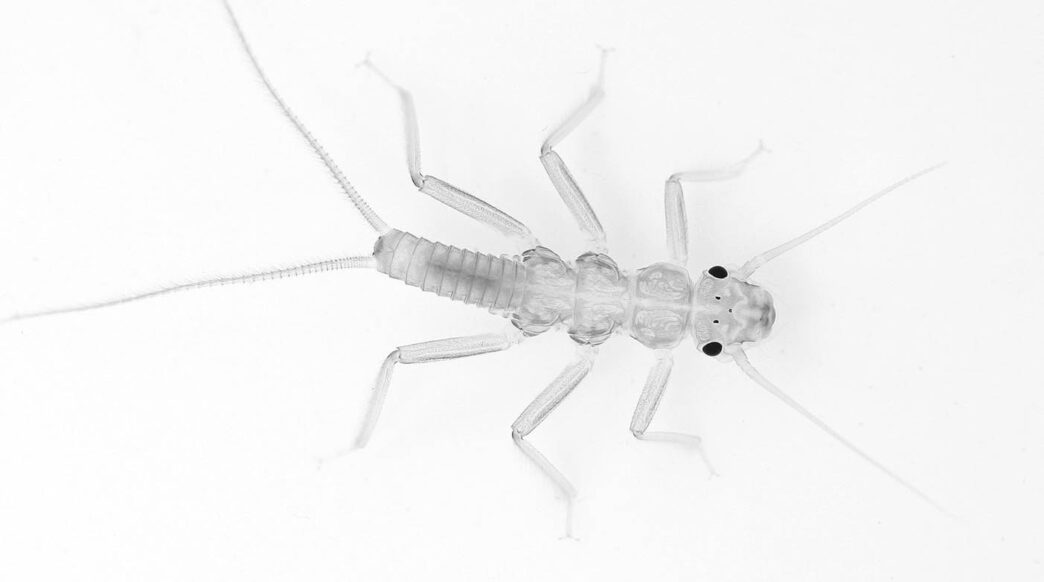

The magic fly is nothing more than a drab white nymph. I can sense the droop in your shoulders and the slack in your jaw. Just when you were anticipating something new and improved, you’ve been offered a thing that is bland, uninspired, and really boring. That’s why it won’t sell.

All nymphs molt repeatedly throughout their lives. No matter what color the nymph, when it hauls out of its exoskeleton, it is a soft, pale, white ghost of itself. For about half an hour, this white nymph has little structural integrity, and while it waits for its shell to harden, it is subject to the whims of the river. An errant waft of current or perhaps a slight shift of the rock it is hiding under will send it helpless into the drift.

Every single nymph in the river is repeatedly subjected to this hazardous experience. Fish know it. A white nymph tumbling down a relatively dark streambed might as well put a flashing fluorescent sticker on its forehead that says “Eat me!”

Consequently, there is never, ever, a wrong place and time to fish a white nymph. They are in the drift every day of the year. It’s only up to you to decide the hook size by tipping over a few rocks to assay the current bug population.

White is one of the easiest of all colors to see underwater. Strictly speaking, according to the additive color theory of white light, white is not a color at all, but the blending of all of the colors emanating from the sun. A simple prism or water droplet will fracture this white light into bands of ultraviolet (UV), violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, red, and infrared. A white nymph looks white because it is reflecting all of these colors together.

Unlike humans, trout can see ultraviolet and to some extent infrared. Historically, it was felt that only juvenile salmonids could perceive UV, but in the past decade, scientists have found that the UV receptors don’t disappear with age, but are simply lost to certain spots on the retina, only to emerge in other areas. The current consensus is that salmonids of all ages can see UV very well and that its perception plays an important role in the life of trout, salmon, and many other fishes.

This poses a dilemma when choosing or tying a trout fly. How do we know what the fly looks like to the fish if we can’t see the same colors as the fish does? The simple answer is that we don’t know. However, since white is the reflection of all the color wavelengths in sunlight, it is a pretty darn good guess that those reflected waves don’t stop at violet, and that ultraviolet is also being reflected. So the white nymph that we see is likely to be pretty similar to the white nymph a trout sees.

Over the past two seasons, the market has been flooded with flies and tying materials purported to reflect UV and hence be attractive to trout. Some of these manufacturers “prove” this UV light reflectance by submitting their product to UV black lights, which ignite the product into bright and wild hues not seen under normal light conditions. What does this dog-and-pony show tell us about the UV-reflecting qualities of the product? Not a damn thing.

UV fluorescence is a world apart from UV reflectance. Fluorescence is the process whereby an electron is excited by a wavelength of light (in this case, invisible UV) that causes it to release the energy in a different wavelength that is visible. Some creatures, such as scorpions and coral, fluoresce under a black light, but I’m pretty certain this a rare phenomena in your favorite trout stream. And when was the last time you saw a trout wearing a UV headlamp? The Spirit River website does an excellent job of detailing the differences between the UV reflecting and UV fluorescing properties of their materials.

Fluorescence does have its place in the fly box, but only because it makes the pattern stand out in true colors in deeper or dirtier waters than it would otherwise. I always tie my Goblin streamers with fluorescent orange or chartreuse rabbit strips to give them more pop. This is simply an eye grabber. I am not attempting to imitate something in nature.

UV reflectance is what trout see. Many insects and baitfish that trout feed on reflect UV to one degree or another. I have a specially modified Nikon camera that captures UV light and displays it as any color I choose. The color is not accurate, of course, but at least I get a general idea of what is reflecting UV and what is not. It varies considerably, but most bugs have some sort of UV reflectance.

Reed Curry has spent untold thousands of dollars on the coolest UV photo gear available. His stuff makes my camera look like used socks from the Salvation Army. He has photographed the UV reflectance of many, many dozens of bugs, baitfish, commercial flies, and fly-tying materials. These photos are displayed in his book The New Scientific Angling: Trout and Ultraviolet Vision, which I have reviewed elsewhere in this magazine.

UV reflectance is an important component of fly selection and design. It wouldn’t hurt to add a smidgeon to your wings or dubbing, but don’t overdo it. As a brief and very incomplete guide, adult dragonflies and damselflies generally reflect a lot of UV from their bodies. Caddisflies reflect little or no UV from their wings, and only a trace from their bodies. Mayflies vary greatly, even within the same species. As an example, in the Gray Drakes (Siphlonurus), two very similar looking subspecies display wildly different UV signatures from their wings. Outside of the white molting state, however, nymphs generally show little UV reflectance.

Algae and plankton can be very effective reflectors of UV. Reef fishes have been documented targeting baitfish that don’t reflect UV, but whose opaque forms create nice silhouettes when their background is a bright haze of UV-reflecting plankton. Perhaps your black bug with no UV reflecting qualities at all will be the winner as we play and experiment in the world of UV materials. My bet, however, is on the white nymph.