California is experiencing one of the most prolonged and severe droughts in living memory. It is a drought for the record books, and relief is a desert mirage away. There are few ways to put a positive spin on the situation. As Jerry Garcia sang, “a box of rain will ease the pain.” We need a big box.

My good friend Brant Oswald has the best way for anglers to deal with drought conditions. He calls it “the twofoot presentation.”

Brant is known as the Lord of the Spring Creeks. At least, that’s what I call him, though I’d never be so crass as to embarrass him by writing it out loud in public. Though he is rightfully famous for his ability to guide neophytes successfully over some of the most technically challenging waters in the world, he is also adept at drycleaning freestone rivers and vacuuming finicky trout from lakes.

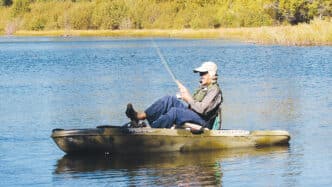

Brant is the Swiss Army knife of freshwater fly fishers, and over the decades, he has refined one of the most effective fly-fishing presentations in all of angling history. Instead of doing rodeo tricks with a fly rod to circumvent an errant eddy, snagging branch, or inconvenient rock, he employs a presentation that goes like this: one-foot moves, and then the other. Thus, the two-foot presentation. Brant is adamant about getting into position. “Find the best spot from which to present your fly, and everything else pretty much falls into place.” The two-foot presentation is key to dealing effectively with drought. Don’t succumb to routine habits and cast to the tepid pools of your go-to trout stream, and don’t quit fishing because the water is so warm that any trout you catch will go belly up and turn into crawdad food. Make a two-foot presentation and go somewhere else. Right now, for Lisa and me, somewhere else is in the mountains of Montana, which experienced a snowfall last winter that was 20 percent above normal. The fishing is predictably fantastic and will continue to remain so right up to the time we leave here in the fall. Northeastern Utah, Wyoming, and Montana are all within a long day’s drive from California. If you can pull off a four-or-five-day vacation, the fishing is within reach and well worth the effort.

Or go to the ocean. The ocean hasn’t experienced a drought; indeed, due to climate change, it is rising and growing measurably closer to your doorstep. Unlike Montana, the Pacific is at most a few hours drive for the average California fly fisher. From a beach, a rock, off a marina, or even from a small boat, you can get your fly-fishing fix. Most experts would argue that saltwater angling requires a specialized and heavier setup than a normal trout fly-fishing rig, but your routine 6-weight will be just fine for infrequent, casual angling. Though you might, at times, be undergunned (what’s the worst that can happen?), mackerel, flounders, surfperch, and rockfish can be successfully pursued with your 6-weight trout rod and small streamers. Don’t be intimidated by the ocean. Approach it like a really big and foul-tasting lake. Rent a boat from one of the many coastal operators for a quick and cheap way to get out over the kelp and make light-rod fishing even easier.

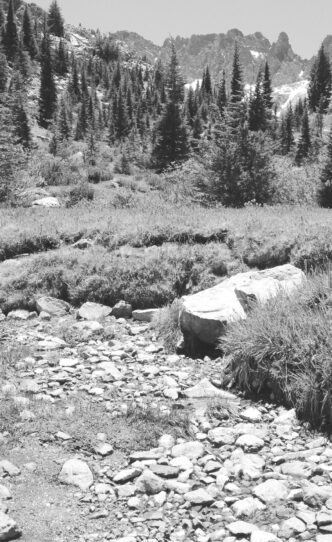

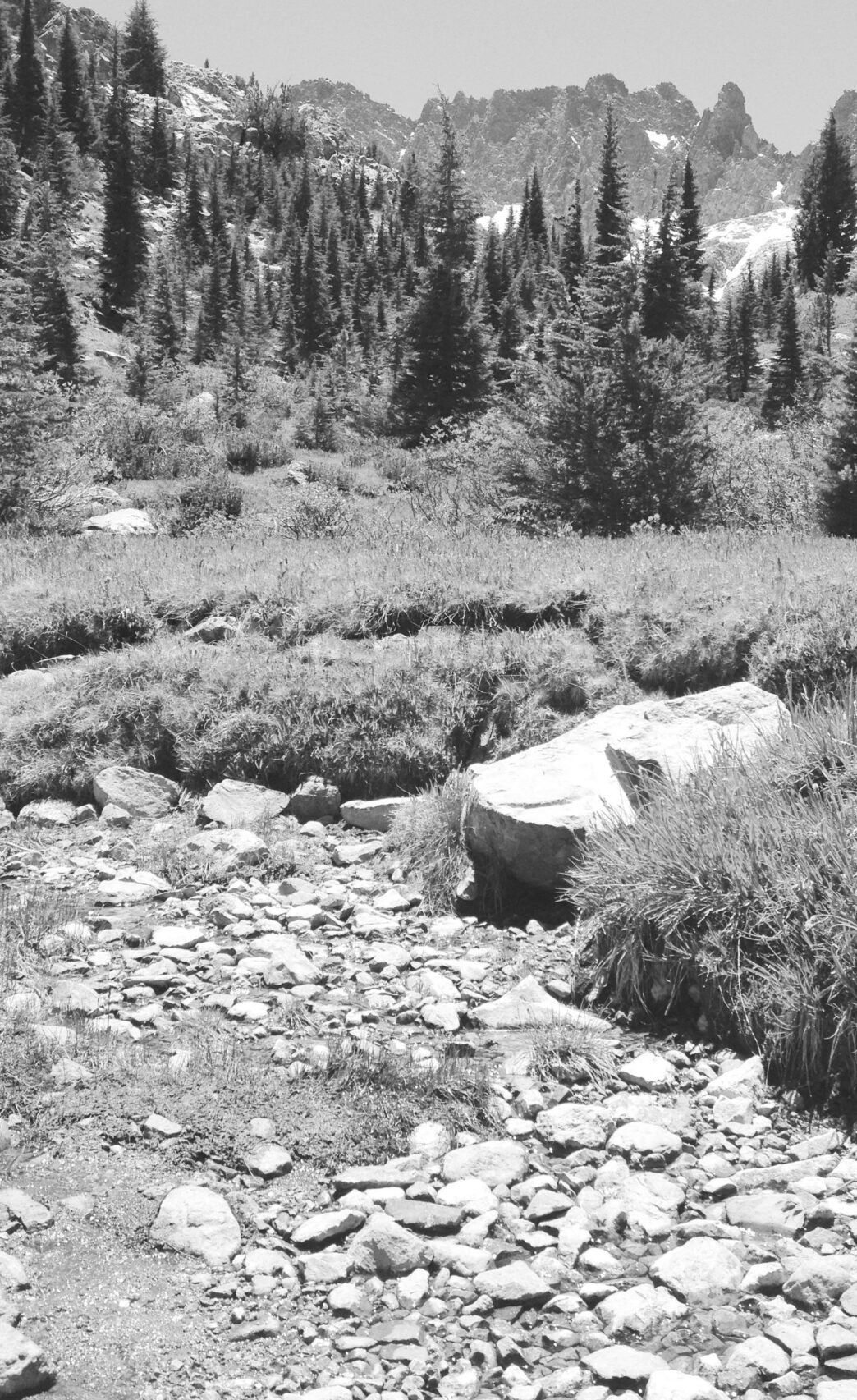

Most higher-elevation rivers and lakes will remain quite fishable through this drought, too. A few weeks ago, Lisa and I made another two-foot presentation and backpacked into the headwaters of the San Joaquin River in the high Sierra. Even at 11,000 feet, we were reminded of the drought. Seasonal creeks that normally run dry in September were gravel beds in mid-June. Just the fact that we were hiking through the high country in mid-June was a testament to the lack of snow. Rivers were low, but compared with the Truckee area, still icy cold, and the fishing was great.

But the drought should prompt other and more far-sighted responses from anglers than just seeking out new waters to fish. It’s an opportunity to reflect on our fisheries policies and how to improve them. Resistance to change is built into the way things are done around here, but past successes suggest that the stresses imposed on our fish and our fisheries by the drought can be the opportunity for making changes that will benefit both in the years to come.

In the late 1960s, Dick Vincent, a fisheries biologist for Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, fought inertia within the agency, angry business owners, and headstrong anglers to experiment with the concept of allowing naturally reproducing “wild” trout to populate a river entirely, rather than augment them with hatchery fish. Even fisheries biologists stuck in the rut of “This is the way we’ve always done it” and “Good enough is good enough” chided Vincent for his risky proposal. It was a fistfest, and for once, inspired biology won over politics. In less than three years, Vincent’s experiment on the Madison River was such an overwhelming success that not only did Montana respond by implementing “wild-trout” management on all of its rivers, but other states, including California, woke up and slowly, even if only partially, embraced the practice.

Fisheries biologist John Dienstadt was given responsibility for the incipient Wild Trout Program of California’s Department of Fish and Game. Dienstadt did an incredible job of introducing the state (which was largely at odds with the concept) to wild-trout policy and the catch-and-release mindset. Not only did he manage to convert thousands of anglers to a new way of fisheries management, he did it despite some resistance within his own belief system. John is an elder in the Mormon Church, where the faith holds that fish are put here by God for us to eat and that we shouldn’t play with our food. John and I spent a long rainy afternoon holed up in his pickup truck at Milton Reservoir, debating the conflict between his religion and his job. I went home with a very deep respect for John and his devotion both to his personal values and to developing the best catch-and-release practices for the state.

The anglers, guides, fly shops, and businesses that fought the likes of Jim Vincent and John Dienstadt are now reaping the rewards of their forward-looking policies. Under direction of Dave Lentz, the Wild Trout Program continues to deliver world-class fishing, and its offshoot, the California Heritage Trout Program, envisioned by Chuck Van Geldern and Eric Gerstung some three decades ago, has taken root and been developed and directed under the enlightened guidance of Roger Bloom. To suggest that wild-trout and heritage-trout management has been well received by the public would be a vast understatement. But we can do more.

Once again, Montana is leading fisheries management innovation with “hoot owl” regulations. When Montana rivers reach 73 degrees three days in a row, those waters are closed to fishing between 2:00 P.M. and midnight. It is well understood that warm water and the stressors encountered by hooked fish are a lethal combination. At first, businesses, politicians, guides, and anglers railed against the shortened hours and the “taking” of their fishing opportunities. Montana reaps some $2.75 billion a year in revenue from visiting anglers, and self-serving experts feared this income would be threatened by decreased angling opportunities. As it did with wild-trout management, the health of Montana’s fisheries flourished under the “hoot owl” concept, as its popularity. Today, “hoot owl” regulations are not only accepted, but praised and embraced by the same people who originally fought them.

California has no such thing as “hoot owl” closures to protect its fisheries. When I asked a spokesperson from California Department of Fish and Wildlife why we didn’t initiate “hoot owl” regulations to protect our trout during this drought, I was told quite bluntly that their directive was to open up fishing opportunities, rather than to shut them down.

It was this same quest to “open up opportunities” that resulted in the removal of seasonal fishing closures that were originally designed to protect spawning fish. The change to a year-round open season has been received with mixed reviews. It was certainly a worthwhile experiment and has been a success in some places, but it was promised to be an “adaptive management” policy. As with most bureaucratic rules, year-round fishing seems now to be cast in concrete and not at all adaptive to fluid situations such as this severe and prolonged drought, which is producing excruciatingly low flows in the late fall and spring, when trout are moving into vulnerable shallow waters to spawn.

We fishers are smarter than accepting politically motivated, short-term “fishing opportunities” in exchange for long-term costs to the health of our fisheries. In the Truckee area, for example, Trout Unlimited’s Truckee Chapter #103, the Tahoe Truckee Fly Fishers, Truckee area guides, and local businesses are stepping up where the Department of Fish and Wildlife has failed to act. Via club meetings, social media, signage, and self-regulation among guides, the word is being spread to stop fishing when waters get above 70 degrees (California Trout has voiced its support, as well). Voluntary “hoot owl” regulations are being encouraged and adopted elsewhere, and the CDFW is belatedly following Truckee’s lead (see the sidebar below), but only on a voluntary basis. At the state level, we can and should do much better.

Fishing During Drought

Suggestions from the State of California

Editor’s note: The California Department of Fish and Wildlife released the following drought-related advice in mid-August.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) is asking trout anglers to be mindful about fishing in the state’s waters and the effects their catch can have on fish populations. As the summer progresses, the effects of the current drought on California’s wildlife continue to mount. Aquatic wildlife are especially vulnerable as streamflows decrease and instream water temperatures increase, exposing cold water species such as trout to exceptionally hostile habitat conditions. Because of the lower water levels and accompanying higher water temperatures in many California streams, many trout populations are experiencing added stress, which can affect their growth and survival. Many of California’s wild trout anglers have adopted catch-and-release fishing as their preferred fishing practice. Careful handling of a trout after being caught with artificial lures or flies allows for the possibility of trout being caught additional times.

However, catch-and-release fishing during afternoon and early evening in streams and lakes that have elevated water temperatures may increase stress, hinder survival and increase hooking mortality for released trout.

“Please be mindful of the conditions when you are fishing,” said California’s Wild Trout Program Leader, Roger Bloom.“Afternoon and evening water temperatures may be too warm to ensure the trout being released will survive the added stress of hooking, fighting, and sustained exposure to the warmer water that builds up during hot days in summer and fall.”

Some of the state’s finest trout streams have special angling regulations that encourage or require catch-and-release fishing. In waters that may experience elevated daytime water temperatures (greater than 70 degrees Fahrenheit) the best opportunity for anglers to fish would be during the early morning hours after the warm water has cooled overnight and before the heat of the day increases water temperatures.

These low water conditions and warmer water temperatures are happening across the state — from Central Valley rivers flowing below the large foothill reservoirs to mountain streams in Southern California and in both east and west slope Sierra Nevada streams.

“Enjoy California’s outstanding trout fishing and help us to keep wild trout thriving by using good judgment,” said CDFW Fisheries Branch Chief, Stafford Lehr. “Fish earlier and stop earlier in the day during these hot summer days ahead.”

Protective measures for catch-and-release fishing during the drought include:

- Avoiding fishing during periods when water temperatures exceed 70 degrees Fahrenheit (likely afternoon to late evening)

- Playing hooked trout quickly and avoiding extensive handling of fish

- Keeping fish fully submerged in water during the release

- Utilizing a thermometer and checking water temperatures every 15 minutes when temperatures exceed 65 degrees Fahrenheit

- Stopping angling when captured fish show signs of labored recovery or mortality

- Utilizing barbless hooks to help facilitate a quick-release

Although other states have used temperature triggers to close recreational fisheries, California does not currently have a legal mechanism in place to accomplish that. Historically, the CDFW has requested voluntary actions by anglers to avoid catch-and-release fishing in waters like Eagle Lake and the East Walker River during periods of elevated water temperatures. At present there are local angling groups in Truckee encouraging anglers to participate in a volunteer effort to avoid fishing in the afternoon and evening.

As we move through these extreme conditions, the CDFW is asking anglers to help protect our state’s native and wild trout resources. Anglers interested in researching local conditions prior to a trip should contact local tackle shops, check online fishing reports or contact a local CDFW regional office. Anglers should also consider using a hand-held or boat-mounted thermometer to assess water temperatures while fishing.