Every year for the past 36 years, I’ve been snorkeling and scuba diving the Truckee River. One day during the first week of June, Lisa and I once again hauled the dive gear over the railroad tracks, through the sage and bitterbrush, and down to the river. As I get older, the load gets heavier, but when I slide through the quicksilver film and become weightless, the years slip away as if I were entering the realm for the very first time. The entire world transcends into something so vastly different from our everyday existence that it never ceases to blow my mind. There are very, very few things I’d rather do than swim inside a river.

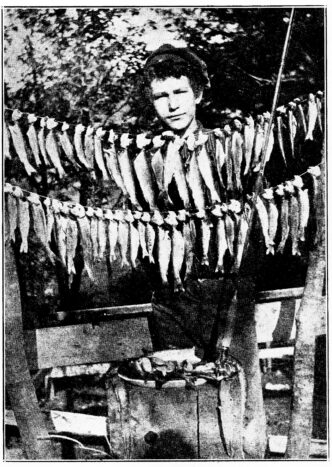

Even in drought years, when the river looks clear from above, the water is still loaded with debris from runoff in early June, and visibility is reduced to just a few feet. So it was this year. We should have waited for better conditions for this dive, but I’ve always been one to open my presents early and sneak a bite of dessert before dinner, even if the dessert isn’t very good. The winter of 2011–2012 was exceedingly dry; the Truckee River Basin received less than half its average snowfall. Over the past three and a half decades, I’ve experienced drought winters, but this one was unique in that it was not only dry, but never sustained any long, hard freezes. This dive therefore presented a unique and interesting picture. The river is crawling with crayfish unlike anything I’ve ever seen this early in the season. Trout numbers are seemingly depressed, and whitefish have largely gone missing. (This scenario may be different below Boca Reservoir, where flows have been higher.)

Signal crayfish were planted in Lake Tahoe in the early 1930s. Their numbers remained low, apparently because the trout dined on them. In the mid-1960s, Mysis shrimp were introduced to Tahoe to feed its lake trout and kokanee salmon. The Mysis wiped out the native Daphnia (water flea) population that was the foundation of the lake’s food web. The trout switched from eating crayfish to eating Mysis shrimp, and the crayfish population started to climb. In the mid-1970s, there were around 60 million crayfish in the lake, and today, only 30 years later, there are over 220 million. There is no indication that this population explosion is going to slow down anytime soon. Crayfish have become so abundant in Tahoe that a commercial fishing operation has been permitted to start harvesting them this year for the food trade. Comparing Lake Tahoe’s crayfish numbers with those in the Truckee River, which flows out of Tahoe, is like comparing apples and oranges, however. Unlike the lake, which is a very static environment, the Truckee River is extremely dynamic, with naturally high and low flows, as well as artificially manipulated flows via reservoir releases. Yet despite the obvious difference between the lake and river dynamics, my personal observations suggest that the crayfish populations in the river also have steadily increased over time.

The biggest threats to crayfish are flooding events that rock and roll the streambed and crush the hapless crustaceans with rolling stones and bouncing boulders. In low-water years, when runoff and rolling streambeds aren’t an issue, the big killer is extended hard-freezing temperatures. Anchor ice, especially in shallow water, freezes to the streambed. When the ice gets buoyant enough, it floats to the surface and carries with it a load of rock and gravel. This stone-studded iceberg drifts downstream and masticates every living thing in its path. Crayfish that haven’t burrowed deep into cover get ground into paste.

The dry, warm winter of 2011–2012 resulted in low flows and no anchor ice — perfect conditions for crayfish. At first blush, this might seem like a good thing for Truckee anglers. What could be wrong with a bumper crop of crayfish?

For one thing, crayfish have to eat, and high on their list of preferred foods are immature caddisflies, mayflies, and stoneflies. Another problem with crayfish is that a trout that keys in on them has to feed only a few times a week to satiate its hunger. The fewer times a trout opens its mouth to eat, the fewer chances you have of putting something sharp in there.

Over the past decade, the whitefish population in the Truckee has been declining for no apparent reason. In response to the decline, the bag limit was reduced from 10 to 5 fish. Unlike trout, which bury their eggs under gravel, whitefish broadcast their eggs over the rocky substrate, where they settle into interstitial spaces in which they mature and hatch. In the Great Lakes and in Europe, broadcast spawning lake trout and whitefish populations have been locally impacted by invasive crayfish feeding on their eggs. Could the dramatic increase of the signal crayfish population in the Truckee be at least partially responsible for the concomitant decrease in its whitefish population? It would seem to be a logical conclusion, but as Department of Fish and Game scientist Jeff Weaver notes, “as in any species decline, a smoking gun is often elusive, at best.” There is probably more going on than meets the eye.

Other than by producing an abundance of crayfish, how else might the dry winter affect us? Grasshoppers should be in rare form. Already grasshopper nymphs are abundant in the drainages of the Truckee, Yuba, and American Rivers. The short, mild winter was great for hopper survival, and the unseasonal March rainfall on the west slope of the Sierra gave the grasses a nice bump, which can only help the grasshoppers push into summer.

Yellowjackets in California are highly susceptible to fungal attacks during prolonged wet autumns. Last fall was about as nice as it gets if you are a yellowjacket hunkering down for the winter. Expect to see an abundance of these guys by midsummer, and come September, trout should have eaten enough to be suckers for their imitations.

Finally, one of the best things about a dry winter is that the high Sierra opens early and mosquito season is brief. Now is not too soon to plan a few forays into the backcountry.