A Tale of Two Spiders

I walk up the dirt road gingerly picking my path around ruts and deadfall. I’m thinking about the flows, the light, the fish. Suddenly an explosion of black feathers just feet away—turkey vultures blast upward. I look down and see fresh kill, my eyes drawn into the dark socket that once enclosed the deer’s eye. What killed it? And when might it return for its cache? I consider returning to my truck, but nervous energy propels me forward. What are the chances that a mountain lion is going to mess with me when its cupboards are full?

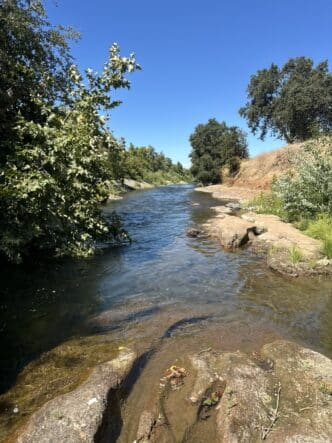

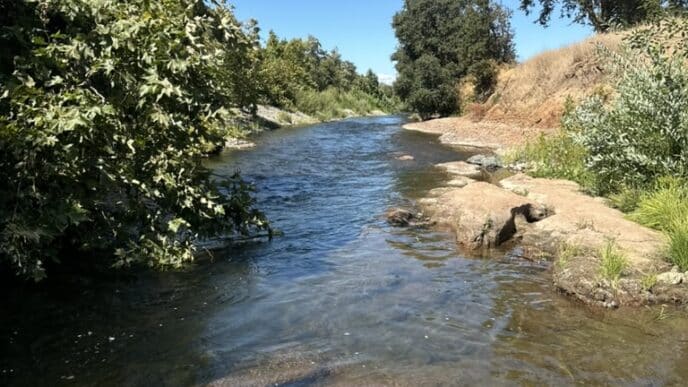

I refocus on my path, trying to ignore my twitching eyelid; when was the last time that twitch betrayed me—biology class finals, decades ago? I concentrate on my mission to test two flies at dusk on a remote stretch of river. This part of the river isn’t known for good fishing, but my son and I have found large rainbow and brown trout here. This is our “secret spot,” and we have never seen anglers here or anyone else.

Recently, two spiders captured my imagination and my time at the vise. I now carry them to their christening. One, the Mallard Spider, preceded my generation, and the other, the Platte River Spider, followed it.

Looking back through some older fly-tying books, I had stumbled upon and been intrigued by the scene described by Jack Dennis, in which his grandfather would troll the Mallard Spider on Lewis Lake in Yellowstone National Park. The fly was born when pioneering Jackson Hole fly shop owner and guide, Bob Carmichael, collaborated with the California longshoreman and steelhead fly tyer, Roy Donnelly, after World War II to create the fly. I could never forget this statement by Jack Dennis regarding the Mallard Spider, “Hidden back in the antique fly boxes of some of the great old-time fly fishermen, you will occasionally find a long-forgotten pattern whose day may have come again.” I wanted to find out if the Mallard Spider’s time may have come again, at least here and now in the secret spot.

THE PLATTE RIVER SPIDER

The modern fly I carry, the Platte River Spider, leapt from a page of Charlie Craven’s book Tying Streamers. Like the Mallard Spider, the Platte River Spider is wrapped with marabou and mallard, but with a feathered wing tied atop. I was drawn to the elegance of the Platte River Spider, which Craven asserts “may just be the prettiest modern trout fly out there.” The pattern was designed by the steelhead fisher and former guide and drift boat builder, Chris Schrantz.

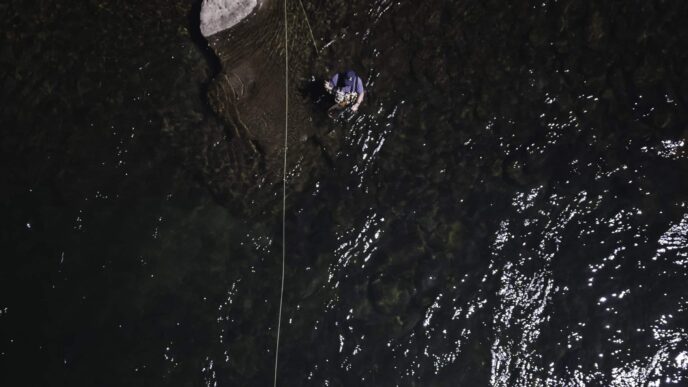

I tie on the Platte River Spider first. There are brown trout in this reach, and I want to test if the orange and yellow hues of this spider will trigger one of the big fish we have found here. I pitch the line into the current and let it swing into the seam 50 feet down; I pull in and cast again. On the third swing, I feel an abrupt jerk, then slack. It’s a break-off. A break-off of the only Platte River Spider that I have.

THE MALLARD SPIDER

Looking up and around, I now see and feel the deepening dusk. As I’ve aged, I have increasingly told myself that venturesome risk to a life well lived is acceptable. I relate to Norman of A River Runs Through It when he says, “I usually fish the big waters alone, although some friends think I shouldn’t.”

Yet in the half light of the canyon, my courage begins to fade in equal measure with the diminishing daylight. It’s a long walk past the deer carcass back to the truck, and there is no cell signal for a call out. For a moment, thinking of the darkening trail, I consider leaving.

But I have come here specifically to fish streamers at dusk. I tie on the Mallard Spider, a pattern over half a century older than the Platte River Spider.

Six or seven casts into the same seam, I feel a strong tug and solid connection.

It’s a powerful fish that takes several minutes to land. As I bring it in, my attention is diverted by a flash of more color at the mouth than I expected to see—the Mallard Spider I am fishing is mostly muted tan and yellow. Then I see bright yellow on the other side of the fish’s mouth from the Mallard Spider—the Platte River Spider! This is the fish that broke off the Platte River Spider earlier. It now has the two spiders, one on each side of its mouth.

The novelty of the sight makes me smile. But then there is something else, something more than the serendipity of two flies in one fish. I feel the tug of history, alongside the lure of the contemporary, in seeing the post-war spider joined with the post-millennium spider. It’s this wild fish’s response to these patterns, one by the longshoreman and the other by the drift boat builder. It’s a taste of heritage in the sport, something that’s always been ineffable for me.

I recover the Platte River Spider, remove the Mallard Spider, and unconsciously start crossing the cobbles toward the trail. I’ve always thought of fishing with the flies I’ve tied as tinkering. Something in a magazine or on YouTube might catch my eye and move me to the tying vise. The pattern could be created by anyone from anywhere. But today became more than just tinkering. My mind drifts back to the longshoreman and the boat builder, two people who didn’t know each other, who couldn’t have known each other across the gulf of time. Still, their ingenuity has come together here, in one place, one moment, with one fish. I feel privileged to be part of it.

Now I hear a soft, slow, serene call. A mourning dove? An owl? I look up. It must be an evening owl, not a daytime dove, that accompanies me on this gravel bar. I realize that I’m no longer nervous in the fading light. Or perhaps the apprehension has changed to a charged awareness, just part of the fullness of being in nature. I turn back to the river, and, in the quarter-light of the canyon, reinitiate the cast, the ageless twilight rite.

Tying Notes

The spiders in this story, though separated by decades, share this foundation: both were designed by West Coast steelhead fishers and fly designers, bringing their skills and insights to the Intermountain West. Both flies use mallard and marabou, and both use red or orange fibers for the tail.

The Mallard Spider

Hook: Mustad 9671, sizes 2-10

Thread: Black, tyer’s choice

Tail: Red hackle fibers

Body: Yellow floss

Ribbing: Gold embossed tinsel

Underwing: White or light-yellow marabou

Hackle: Mallard breast feather

Tying tips: The tail is tied such that it extends one-half to one-third of the shank length past the bend. The body is simply yellow floss with tinsel ribbing. The marabou is tied in on top, just in front of the body, and the mallard is wound around the shank in front of and over the marabou.

Step-by-step tying instructions for the Mallard Spider are in Jack Dennis’s book, Western Trout Fly Tying Manual, Volume II (1980).

The Platte River Spider

Hook: Tiemco 200R size 4

Thread: Black 70-denier UTC

Tail/Underwing: Red or orange Amherst pheasant tail fibers (or similar)

Body: Yellow and brown marabou

Hackle: Mallard flank feather dyed wood duck gold

Flash: Root beer Krystal Flash

Wing: Yellow and furnace Chinese rooster neck hackle

Hackle: Mallard breast feather

Tying tips: Amherst pheasant tail fibers are specified, but I have found that strung guinea feathers are a feasible substitute. The yellow and brown marabou should be selected to have similar fiber length, about two shank lengths long, as these feathers are paired and wrapped. The mallard feather should have fibers at least as long as the hook shank; the feather is wrapped over the marabou. The yellow and furnace hackles should be the same length as they are arranged to form the wing—two furnace feathers bracket two yellow hackles.

Detailed tying instructions for the Platte River Spider are within Charlie Craven’s book, Tying Streamers (2020).

To imitate rainbow, versus brown, trout minnows, the tyer can substitute olive marabou and neck hackle for the yellow marabou and hackle specified above.