For those of us who prefer to fish small streams in the high country, this past winter was a time of great uncertainty. For the second year in a row, the snow arrived late — in February, as I recall — and there wasn’t much accumulation. For years now, I’ve preferred to fish only headwaters, over wild fish and in solitude. So I viewed the drought with alarm.

Last winter, I had planned a midsummer trip to the Tioga Pass area in Yosemite National Park with Laurent, a friend with whom I have been fishing the past several years, both for company and for safety. We had been there before, and I had the pleasure of reintroducing him to fishing small waters, something he had drifted away from. However, as the summer approached, such a trip seemed highly unlikely this year. Of course, there still would be some water and fish, but it seemed almost disrespectful to target fish likely suffering environmental stress. But fly fishers are hopeful, and the anticipation of going fishing is one of our pleasures. I think that all trips, not just angling, have three phases that spread the experience over a longer time: the imagined trip, the actual trip, and the remembered trip. As we began planning for our mid-July outing, however, it looked like we might never leave the Bay Area. In early May of each year, our local paper runs a story about the final assessment of the California Cooperative Snow Survey, which documents the statewide snowpack for water-management purposes. For the second year running, the accompanying photo showed the chief surveyor standing in a meadow near Echo Summit with no snow whatsoever. In science, zero is a data point, but from a trout-fishing perspective, no snow at over 7,000 feet in the Sierra in late April is stunningly bad news.

Then the bad news got worse. I always time a first fishing trip to the Truckee area by a real-time stream gauge on Sagehen Creek. When the gauge reads 10 to 12 cubic feet per second, which it often reaches in mid-June, I consider conditions to be optimal. This year, on May 1, the flow was 4 cfs, too low to consider fishing then or later. On the same date, the snow depth at 9,800 feet in Dana Meadows above where we intended to fish in mid-July was little more than 2 feet. To complete the dismal picture, the Tioga Road opened, free of snow, on May 2, a rare occurrence.

So the objective data suggested that we should forget about a trip to the high country. Headwaters streams typically have a narrow fishable window between declining runoff and low water. A low-snow year narrows that window even more. We expected to have missed it. But Laurent and I had both fished for trout enough since childhood (worms and salmon eggs back then, if the truth be told) to have confidence that we might catch fish in doubtful conditions. So we resolved to roll the dice, and we made our plans.

We aimed for three full days of fishing. Well, actually, as an experienced sexagenarian and a rookie septuagenarian, the term “full” for us really means fishing during banker’s hours — midday. The objects of our desire were the Dana Fork of the Tuolumne River and Parker Pass Creek, both familiar to readers of California Fly Fisher, and the area surrounding the nearby Gaylor Lakes. The Dana Fork and Parker Creek arise just below Sierra Crest peaks at 13,000 feet. The streams join at about 9,500 feet (Parker Creek loses its name), and the emboldened Dana Fork descends to Tuolumne Meadows, joins the much larger Lyell Fork, and both become the Tuolumne River, debouching into Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and then into other downstream indignities.

I discovered these waters perhaps 30 years ago on a lark and became smitten. The reaches up from the confluence of the Dana Fork and Parker Creek are pristine, and a moraine divides the two almost identical beauties. The Dana Fork takes its name from Mount Dana, which looms over it, named for a geologist on the 1863 Whitney Survey of the Sierra Nevada. Who the Parker was for whom the creek was named is lost to history. Long before Europeans “discovered” the area, both streams served as trade corridors between Yosemite Valley, with its acorns and pine nuts, and Mono Lake and its obsidian deposits.

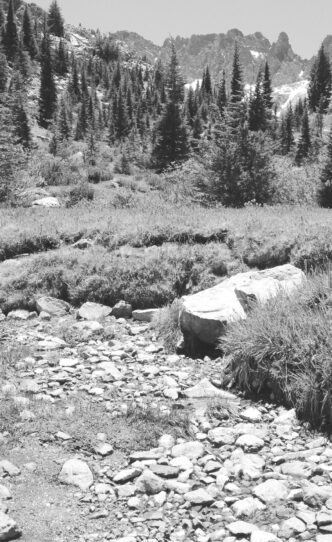

The setting above the Dana-Parker confluence is simply stunning. Both streams alternate between open meadow stretches with gradient-driven flows (no lazy meanders here) and tightened, canyonlike reaches with riffles and pools. Moving upstream, as one comes in and out of tree cover, either 13,000-foot Mount Dana or 12,000-foot Mammoth Peak dominate the scene.

Rolling from the cup, the dice hit the table, and phase two began. We expected low water: a quick check of Yosemite road conditions for construction delays uncovered a dismaying item about Yosemite Falls being all but dry. Yosemite Creek, as the Tioga Road crossed it at about 7,500 feet, seemed quite diminished. Above Tuolumne Meadows is a pullout with a view of the Dana Fork below the confluence. We stopped, and a sense of relief set in. The flow had held up! The question remained whether Dana upstream or Parker looked fishable.

The next day, when, observing banker’s hours as usual, we opened the bank at about 10:30 in the morning, we stood at the confluence of the two streams and relaxed. Either would be fishable. Because Laurent had never fished Parker Creek, and I had not fished it for over 10 years, that’s where we started.

We immediately caught trout, and this continued for about four hours as we alternated positions up the stream. The numbers and species were as I had experienced in the past — countless brookies, a smattering of rainbows, and one lone brown, most taken on Humpies. The size of the fish was variably modest. We missed many and brought many others to hand. A multitude of lupines enhanced the aesthetic experience. And for a frisson of excitement, we had a thunderstorm close by. The entire Sierra range had been experiencing stormy weather for several days. The flashes and crashes came near, but we were in a defile and hunkered down in relative safety with fiberglass, not graphite rods. The upside was that the cloud cover mitigated the downside of fishing banker’s hours, often in full sunlight. Also, we wisely reconsidered our plan to fish the totally open Gaylor Lakes Basin the next day and decided to return to the confluence and fish up the Dana Fork.

We did so, and with slight differences of terrain and fish avidity, the day played out as the day on Parker Creek had. Again we caught countless brookies, a scatter of rainbows, and one lone brown. Laurent took the brown and the hat trick. With about 50 yards to go, we traded rods and both caught fish. With two unexpected and immensely satisfying days, we called it a trip and went home a day early. Perfect.

You just read phase three: the remembered trip. Trout fishing in time of drought? It can be done — if you roll the dice and are lucky.