“There it is! Right there on the edge of the seam, behind the pyramid-shaped rock.” Just like that, the fish appeared, hovering almost casually — a huge brown trout, for sure. The big spots and butter-yellow color were becoming more and more vivid as I stared at the fish.

I had ducked behind a big boulder as soon as Miles had pointed out the trout to me. After a few more minutes of observation, I decided the time was right to try a cast or two at the big brown. I quickly ran my fingers over the tippet, checking for abrasion and making sure both my tippet and fly knots were sound.

The big Marabou Muddler was sopping wet from being fished for half an hour or so, the deer hair head sufficiently soaked to keep the fly riding deep. The point of the hook dug easily into my fingernail. It was time.

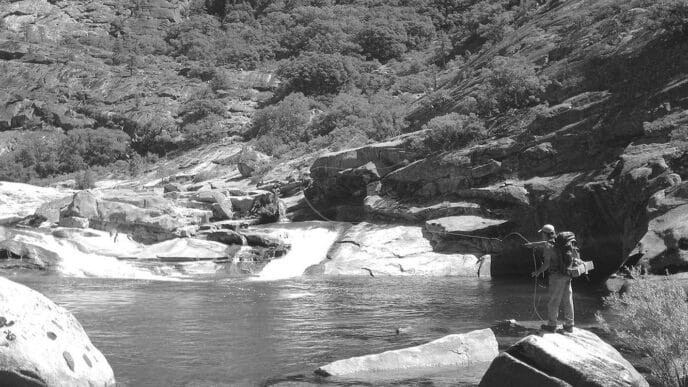

The first cast sent the Muddler to a spot six or seven feet above the fish, and with a quick pull on the line, I brought the marabou-winged fly to life. I looked to the left to locate the big brown, but all I saw was the rapid flash of a moving fish. Then the line yanked hard in my hand as the brown inhaled the fly.

The fish rapidly turned and shot downstream into a large pool — perfect! In the big pool, the fight was almost anticlimactic, because the heavy tippet took a quick toll on the big trout’s energy reserves. Soon, 25 inches of gold and olive were resting calmly in my net. The barbless Muddler slipped easily from the corner of the fish’s jaw, and Miles and I watched in quiet admiration as the fish slipped away into the depths.

“It’s all about the final approach!” Miles proclaimed. I looked over with my favorite “What the . . . ?” expression, and Miles continued, ”You know, spot the fish, figure out what it’s doing, and then make the final approach and catch it!” I thought about it more and decided that Miles was right: It is all about the final approach. Just as when a plane is landing, that’s when everything can go incredibly right or incredibly wrong in seconds. If your final approach is good, you’ll land OK — and land more and bigger fish.

When it comes to catching large trout and other large game fish, the anglers who succeed time and again are often the most careful, methodical, and consistent with regard to their final approach. I’ve been fortunate enough to have fished with some of the best final-approach anglers around, and I’m going to share some of their hard-earned knowledge with you.

Finding the Target

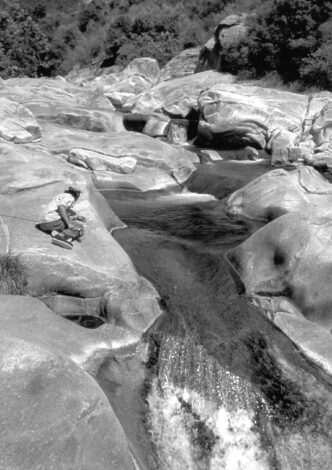

To catch a big fish, you first must first find one. The final approach most often begins with a slow, deliberate stalk along the bank.

Successful final-approach anglers use available streamside cover to shield themselves from the view of the fish, often crawling along the bank to minimize their profile and always taking care to not skyline themselves above places where big fish may be holding. Many of the big fish that I see are visible only after long, patient observation of likely spots. I’ve often spent an hour or two looking over a pool or run carefully, watching for the tell-tale movement of large fish. Many times, as the light changes in a pool or run, fish that were previously hidden from view appear magically in front of your eyes.

I cannot stress enough the importance of patient observation. The more time that you spend studying the water and looking for big fish, the more big fish you will see and eventually catch. I often come across gung-ho anglers who practically run from spot to spot, slapping casts here and there, placing their fly everywhere. Many times, the law of averages works out for them, and they catch fish just due to the sheer amount of water they cover. These guys also catch a big fish every now and then. Most of the time, however, they have probably spooked every big fish they might have had a shot at, 10 to 20 yards ahead of their path. Big fish don’t respond well to loud noises caused by clunking rocks, splashing water, and the banging of a careless wader. Slow down, observe, and be stealthy if you have to wade into position to get a shot at a big fish.

Skills Honed to Perfection

All of the best anglers I know have worked hard at perfecting their casting, water-reading, presentation, rigging, and fish-fighting skills. This isn’t to say that all these folks are great casters. In fact, many of the best anglers I know do not cast artfully — but they’re proficient. These anglers can cast both as far as they need to and as close as they need to with deadly accuracy, even though casting beauty or style points may be lacking. It may not be the prettiest cast you’ve ever seen, but if it consistently puts the fly where it needs to be, then it’s good enough. The best casting practice is on the stream in front of live targets that let you know whether you did it right or wrong immediately.

If you are going to spend time off the water practicing your casting skills, devote plenty of time casting to targets set at all different distances, because the biggest key, of course is being able to put your fly right where you want it every time. If you can put your fly on target every time, you’ll catch a lot more fish. Work on placing the fly on the target, rather than firing the fly at the target. A great, superaccurate cast that slams the fly into the water, alerting the fish, is no better than a cast that lands 10 feet off target. In the ideal presentation, the fly should just appear in the fish’s world without any announcement.

Rigging Skills

Every time that you are on the final approach, you need to make sure that your rigging is right — “right” meaning that all your knots are sound, your hook is sharp, and most importantly, you’ve got the correct rig to present your fly properly to the fish.

Once you’ve spotted a target, you need to decide what fly and rig you are going to use. A common mistake that I’ve certainly made more times than I care to admit is just using whatever existing rig I had on at the time. Without making the proper adjustment to your rigging and just going with what you’ve got, you stand a good chance of ruining your shot.

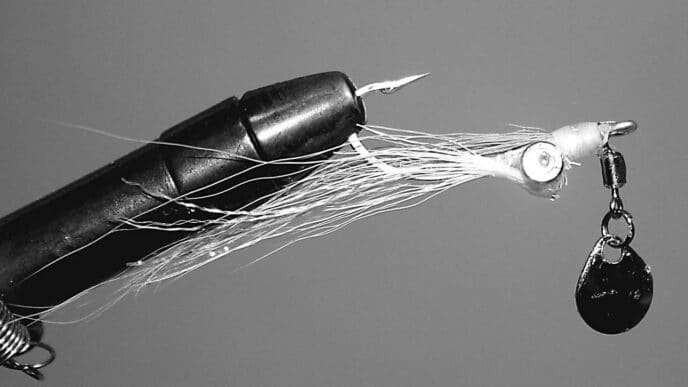

First you have to choose a fly. Most of the time, the offering will be subsurface with a nymph or streamer. On rare occasions, it will be a dry, but that is usually reserved for times when a big fish is observed actively feeding on the surface. I count on subsurface flies to catch big fish. Although it seems like many people’s standard rigging almost always involves a two-fly rig, more and more I find myself choosing a single-fly rig, especially if I’m casting to a giant fish. A couple of years ago, I lost a very large brown that had taken the upper fly of a two fly-rig and then proceeded to swim by a sunken root wad, securely hooking the trailing fly in the mass. The fish was tethered for a moment, but then it swirled back downstream and sheared the tippet. Since that loss, I’ve gravitated to a single-fly approach when it comes to the ones that I really want to catch.

Judging the depth at which a fish is holding and studying the flow of water through that area will give you a fair idea of how much weight you’ll need to add to get your fly to the fish’s level. I use moldable tungsten putty for this task, rather than split shot, because I have better control over weight adjustment and there is no distracting shine from the weight. I think the biggest mistake we make with weighting is adding too much, causing our fly either to sink below the fish’s level or worse, to snag on the bottom. A little bit of experience will make you an expert at weight adjustment. Ideally, your fly will reach the perfect depth on the first cast.

As far as the size and length of tippet goes, let the conditions choose. As a general rule, I like to have a 3-to-5-foot tippet when nymphing, because it sinks to depth quickly and provides a little extra shock absorption.

Depending on how well I can see the fish that I’m targeting, how likely the fish is to be spooked, and on how confident I am in my ability to detect strikes, I may choose to make a final approach cast either with or without an indicator as part of my nymphing rig. On a good day, when I can see the fish well and I’m fishing well, I will choose to go without an indicator. This requires watching the fish very carefully and having commanding control over your drift. I watch the fish for sideways or upward movement as the fly approaches its position. If I see the white flash of the fish’s mouth or a sudden movement that leads me to believe the fish has intercepted the fly, I raise the rod immediately. If I do not come up against the resistance of a hooked fish, I make a back cast out of my striking motion and remove the fly from the drift. I do not immediately cast the fly back to the fishing zone. I wait, reevaluate my rig, and add or subtract weight if necessary before making the next presentation. If I am using an indicator rig on a final approach, I choose the smallest and least obtrusive indicator possible. Most often, I use small yarn indicators that I make myself. I stay away from anything that is normal as far as indicator colors go — no orange, green, pink, or red. I like sky blue, lavender, and other muted colors, I carry quite a few different colors, in order to be able to choose a color that I can see.

When using an indicator rig on a final approach, make sure to cast it well upstream of the fish’s position and make all necessary mends before the indicator comes into the fish’s view. I watch the fish’s behavior until the indicator is within a foot or two of the strike zone. At this point, all attention goes to the indicator. If it does anything contrary to its downstream progress, set the hook immediately. If it’s a miss, back cast the rig out of the zone and reevaluate before making your next presentation.

Using a streamer in a final approach presentation is fairly straightforward. Since almost all of the streamers that I tie are weighted, I choose one with enough weight that I can get the fly at or just above the fish’s level without adding any additional weight to the leader. The ultimate goal is to present the fish with a broadside look at a fleeing or wounded baitfish or crayfish. Again, careful study of the fish’s position and depth will tell you where you need to cast the fly and what mends, if any, will be required to get the fly to the correct depth. Large fish will often come four or five feet for a large meal, so be prepared if you see the fish start to move. That usually means you’re about to get bit!

The Importance of Stealth

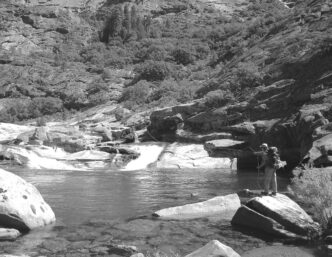

The best anglers I know are a sneaky bunch. They spend their time creeping around, hiding behind any available cover, and peering through streamside branches. Most of them would probably make pretty good ninjas. Pay particularly close attention to your footfalls, both in and out of the water. The vibrations that clunky footsteps send through the bank and into the water or directly through the water are the kiss of death, causing big fish to flee to a safer place. Wading staffs and cleats are necessary evils for many of us, so we must strive for extra stealth if we are wearing one or using the other. If possible, I like to make my final approach from a position on the bank, which is often possible on the waters that I fish most frequently. The less we are seen as an invader in the fish’s world, the more fish we will catch.

Changing Angles

Many times, I have found that changing the angle of my presentation is all that it takes to get the grab. I’ll try a few final approach casts from a given position, but if the fish doesn’t take a fly that I think has been presented well several times, I change my position and angle to give the fly a different look or drift. Moving slightly upstream or downstream from an intended target should be done carefully, and consideration should be given to any rigging changes that might be required.

Sometimes the best angle may be from across the stream. If this is the case, go far upriver or downriver before you cross. Be extra stealthy as you approach from your new position, because it is usually harder to see the fish from the side opposite from where you originally spotted it. Seeing the fish usually has everything to do with ideal light angles and the fish’s position in the water.

The more careful and patient your approach, the less likely you’ll spook your target fish as you move to a different location to cast from. Of course, when choosing a new position or side of the river from which to cast, there’s always the added benefit that you might spot another monster fish on the way to catch the monster fish you’ve already spotted!

Staying Calm

There’s something about spotting a big fish that tends to send some anglers into a mild form of panic. I’ve seen many big-fish shots missed because the angler spotted a big fish and then went all goofy. Panic leads to sloppy casting and erratic presentations that rarely get the job done. When you spot the monster, you need to relax and wait a few moments before making your final approach. A little streamside meditation and visualization will lead to more hooked and landed fish. After you’ve calmed down and your hands have quit shaking, you can go about making preparations for your final approach.

Putting It All Together

Once you get into the routine of the final approach, you’ll find yourself much more relaxed and, most importantly, more proficient when the chance at a big fish comes along. The final approach angler ultimately has little interest in racking up large numbers of average-sized fish. The final approach angler uses a patient, stalking approach: rigs are perfect and casts are accurate. The ultimate reward, though, is when your preparation all comes together with the hooking and landing of a large fish.