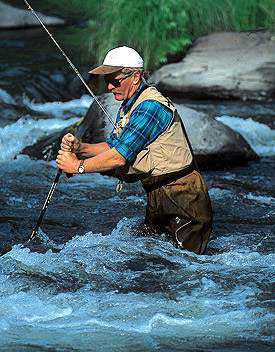

Good wading skills are an essential part of becoming an accomplished fly fisher, as important as good presentation skills and learning to read the water. In California, it is the skillful, aggressive wader who catches the best fish in the Pit, the McCloud, the Truckee, the upper Sacramento, and the many other freestoners across the state.

In reality, few anglers are prepared for the challenges and consequences of wading. It can be fatal to underestimate the dangers of swift rivers. Few of us have had any formal instruction; fewer still know what to do if upset in swift water.

Wading well involves two decisions. First, determine if wading is necessary and appropriate to the water you are about to fish and then decide how to do it in a way that minimizes your impact on the ecosystem, on other anglers in your area, and is safe for you.

WADING GEAR—WADERS, BOOTS, AND STAFF

Breathable waders are easy to walk in and suited to all conditions with appropriate layering. Their only downside is the real risk of filling them with water. It’s very difficult to move once you are immersed unless you are wearing a properly-adjusted wader belt. A wader belt is the essential element of your wading kit. Putting it on should be a part of your routine, like lacing up your boots. I prefer a broad, elastic wader belt that expands as I breathe. Wear it around your waist in moderate water. Cinch it up high on your chest when you wade into deeper water to trap as much air as possible and prevent your waders from filling if you go over the top.

Wading boots come in many styles and sole materials. I favor felt soles because the felt scrubs the rock surface clean under your foot and improves traction. It is true that felt soles can transport harmful microorganisms from river to river unless carefully disinfected, so I have rubber soled boots as well. The Vibram-style sticky rubber soles are free of contamination concerns and are better on dry rocks. I add studs or cleats to all my wading boots, which greatly improves traction, but take the time to learn how to use them and to appreciate their limitations: Metal can be slippery on dry river rocks and can cut a fly line in an instant if you catch it under foot.

A NorCal guide friend liked to brandish his wading staff early in the guide day and exclaim, “This is what catches fish on this river!” The wading staff is the most useful tool an angler can have in bigger freestone rivers. The person with a staff will outfish the wader without a staff every time—and take fewer swims. In small streams, spring creeks, shallow waters, a staff isn’t necessary; but in a rocky freestone river, where the depth and current velocity are factors in wading, it can mean the difference between success and none.

Evaluate a wading staff as if your safety depends on it. If you wade aggressively, sooner or later, it will. The folding staff with a cable connecting the sections and a positive locking mechanism to prevent it from being pulled apart if jammed between rocks is an excellent piece of equipment and currently the most popular staff. I use one when traveling.

In my home waters around Shasta county, a solid staff that will not come apart under any circumstances and will bear your full weight leaning or even falling on it is my choice. Metal ski poles with the baskets removed are ideal. They are typically tempered aluminum, tapered, and very strong and light. Find a used pair or invest in a pair of new poles and keep one as a spare or give it to your fishing buddy. Choose a pole that reaches from the ground to your armpit when you are standing up. This will help you stay upright in the river, reach up for flies in overhead branches, and probe the water ahead for hazards.

Rig your staff as described in the steps below. Clip the cord to the ring in the back of your vest or your wader suspenders or your sling pack strap. It is both out of the way and easily accessible. It floats below you as you fish. When you need it, simply reach behind you, engage the cord and straighten your arm. Your staff will be in your hand, ready for use! For those anglers who disdain staffs, my advice is keep your wader belt high and tight!

READING THE WATER FOR WADING

We first learn to read the water to recognize the places in a river where trout are most likely to hold and feed. Use those same skills to identify hazards and choose a safe passage as you wade:

- Riffles tend to have uniform gravel or cobble bottoms, consistent depth and steady flows. They are generally fairly shallow and can offer good places to cross.

- Runs are often deep and fast. Where the depth allows crossing, they can be good because the bottom is usually consistent and the riverbed fairly level.

- Pools are the deepest part of rivers and the slowest. The tailouts are often broad and shallow, offering good crossing possibilities.

- Flats can also be broad and shallow, with little current. They are perhaps the easiest places to cross. The smooth surface makes it easy to spot underwater obstacles and the steady current and depth are reassuringly predictable.

- Pocket water can be good for wading and crossing because of the many slackwater eddies behind the boulders, but these same boulders can trap a boot and the widely varying currents between pockets can make it difficult to find a reasonable path through.

- Rapids are generally to be avoided because of high current velocity.

Bottom types also have a profound effect on wading. Mud and silt present the risk of sinking in and becoming stuck. Sand will wash out beneath your feet if you stand long in fast current. Gravel is a good even surface, but it too can wash out. Cobbles are solid and reliable, usually too big to wash out while still affording a reasonably level surface. Boulders can offer a little or a lot of current relief but also pose the danger of having your boot caught in between or under boulders. More than one angler has had to unlace their boot to get their foot out from between two rocks. A boot will slide in easily and then become unremovable—here is another use of the wading staff, as a lever to move rocks when your foot is wedged.

WADING STRATEGIES

Routefinding is the key to successful wading. Have a plan before you enter the water. Anticipate problems. Look downstream for the obstacles and hazards you will have to deal with if you lose your footing. If there is particularly hazardous water below, consider crossing or deep wading elsewhere. A simple acronym is WADE:

- Wear your wader belt

- Assess the difficulty and anticipate the problems

- Develop a plan

- Execute that plan

Always keep your staff on your upstream side as you wade. This is critical because it forces you to lean into the current. If you begin to lose your balance, the current will tend to push you upright rather than pushing you over if you’re leaning downstream.

Always have at least two points of contact: both feet or a foot and the staff. Plant your staff. Move your feet. Stop. Plant the staff again and move your feet again.

Keep your body sideways to the current. Facing directly upstream or down exposes you to the full force of the water and makes it difficult to maintain your balance. Standing sideways reduces your profile, giving the current less purchase on you.

Walk with the midstream shuffle: Move your feet along the bottom as though you are blind. Use the staff to probe ahead to check for depth and obstacles. Feel along with each foot and find a secure spot before you commit your weight to it.

Keep a wide stance, staying flexible in your knees. If you need to turn around in really fast water, tuck your rod into your waders or vest, plant your staff directly upstream and place both hands on it. Lean on the staff and rotate with small steps to reverse your direction. Don’t cross your legs as you turn; being cross-legged is unstable and a very difficult position to move from.

If your purpose is to cross the river, do so at a slight downstream angle wherever possible. When fishing upstream, walk the bank or wade in the slow currents along the side. Use the eddies to ease your passage. In a bouldery river, keep your feet on the level as you wade. Go around boulders rather than over them. Move from eddy to eddy. Those little pockets of still water below rocks give you a moment’s rest. The less climbing, the better.

In big water, two anglers wading together can move in water a single angler would find impossible. With two people, the strongest and largest person takes the upstream side. Tuck your rod into the front of your waders. Grab the back of each other’s vest or collar and keep your staff in your outside hand. The collar grab provides a high point of contact that won’t move under pressure and will keep you erect. Shuffle along. Talk to each other. This is a remarkably stable arrangement. With three anglers, the same approach works well, putting the smallest, lightest, or least confident person in the middle.

The deeper the water, the more buoyant you will become and the less traction you will have. There will be a moment when you are at the mercy of the current, even if your feet are still touching the bottom. Stop before you reach it.

Don’t be willing to die for your tackle. There is a story about a fly fisherman who lost his footing and drowned in what appeared to be an effort to hold onto his rod as the water swept him downstream. If you suddenly find yourself floating, you might be able to tuck your rod butt down into the front of your waders or throw it to shore, but don’t risk your life for the sake of a rod. A speedy recovery depends on having both hands free.

The key wading skill is judgment. Be cautious and pay attention to your comfort zone. Try this simple exercise: Put on your waders and boots and immerse yourself in a swimming pool or lake. Try to move. Try to swim. Do this with and without a wader belt on. It is sobering to realize how really difficult it is to move deliberately, even in still water. You need to be completely self-reliant. Have an escape route as you wade. Look for the places where you might get into an eddy. Look for those obstacles that might trap you or injure you. The chances of another person being able to help you are slim. Things happen too fast in moving water. You must be prepared mentally to rescue yourself.

THE DRIFTBOAT APPROACH TO SELF-RESCUE

Eventually, every wader ends up in the water. Most often, it’s a stumble in the shallows where it is a simple matter to stand up. A little water over the top of the waders – wet feet and legs, but no problem. But one day you may find yourself floating downstream without the chance for a quick recovery. When this happens, take a deep breath and think “Driftboat!”

If you’ve ever been in a driftboat with a competent rower at the oars, you have observed that whenever the boat approaches an obstacle that the rower wants to avoid, they point the bow at the obstacle and row away from it, with the stern at a 45-degree angle upstream. If you find yourself upset in fast-moving water, immediately adopt the driftboat position. Get onto your back. Your feet become the bow, your head the stern, and your arms the oars. Scan the water downstream, pointing your feet at the obstacles you want to avoid and backstroking into the current toward the shore. Keeping your body at 45 degrees into the current is critical as you move away from obstacles and towards the shore. Swimming directly across the current will take you further downstream. Swimming upstream will quickly tire you out. Once out of the current, work your way to shore. Don’t be in too much of a hurry to stand up. Get into the slow water first.

BIG WATER

Rivers that are both wadable and boat fishable require a different approach. Avoid crossing above an area of big waves. Without a life jacket, big waves can overwhelm you. The danger lies in being unable to stay afloat. With cold water and no life jacket, you want to get out as fast as possible. If you routinely wade big water—Lower Sacramento, Trinity, Klamath, coastal steelhead rivers—you would do well to consider a CO2 inflatable life vest that fits flat around your neck and chest.

WADING ETIQUETTE

Owning a pair of waders is not a license to step into any water. It is certainly not appropriate in all waters. The fish are much less likely to be alerted to your presence if you stay on shore. Remember that you are in the trout’s environment. Every step disturbs that ecosystem. Be particularly careful not to step on weed beds. They are the condominiums for the bugs. Don’t do anything as you wade that destroys habitat. Wade responsibly. When fishing in a popular area, pay attention to other anglers. Consider how your actions will impact their fishing. Anticipate their moves and adjust your own so you all can enjoy success.

Wading is a foundational skill of fly fishing. It is perhaps the only real hazard the sport presents. Like all the skills, the more accomplished you become, the more success you will have. I don’t mean just in your catch rate. I mean in developing the ability to respond creatively to the fishing conditions you find at that moment. This might mean wading into exactly the right spot to get the precise drift that will put the fly in front of the fish in an appropriate fashion. Or it might also mean having the wisdom to stay out of the water entirely.

Build Your Own Staff

- A ski pole, basket and strap removed. It should touch your armpit when standing up.

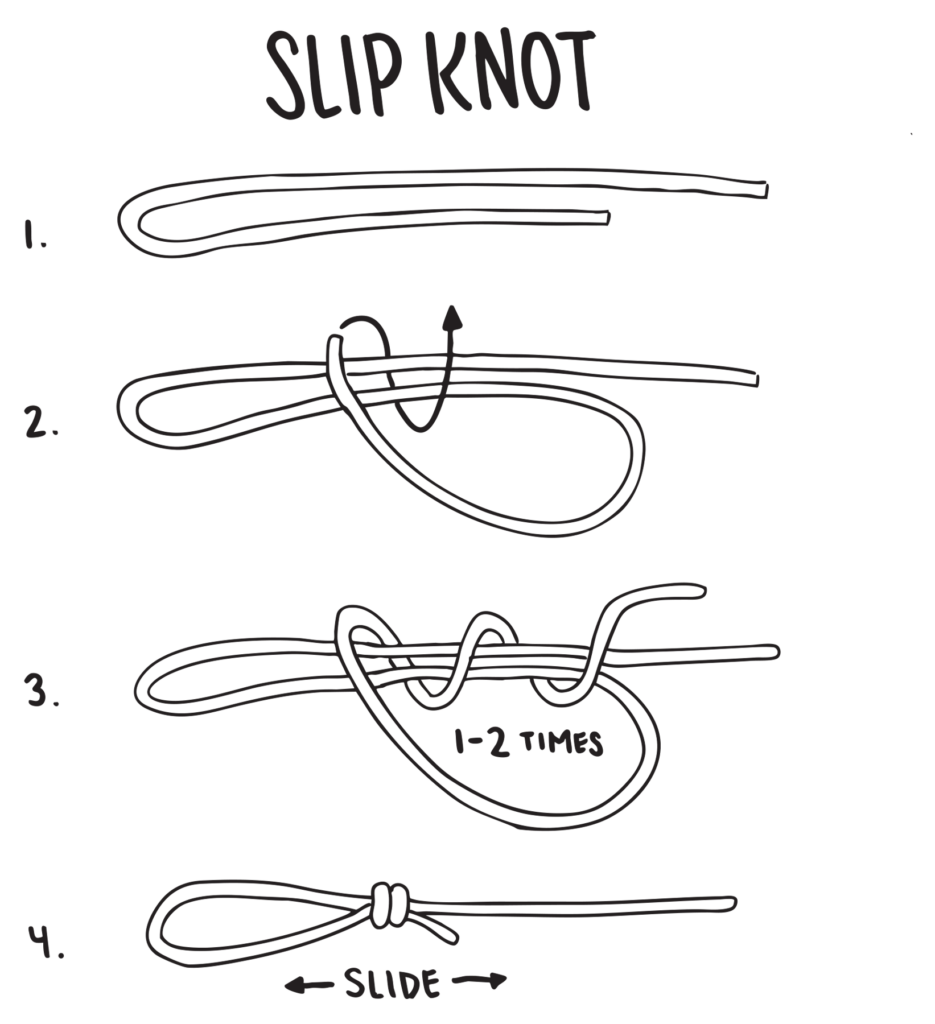

- Just below the handle, attach a length of 1/8th or up to 1/4” nylon cord. Tie the cord around the shaft, immediately below the handle with a locking slip knot and pull tight.

- Determine the proper length of the cord by grasping the handle and extending the arm straight out. The proper distance is from the middle of your back to the staff when the cord is tight.

- Using a slip knot, tie a snap clip or mini carabiner into the end of the cord. Clip that to the back of your vest, wader suspenders, or sling pack strap.

- Check that you have the proper length in the finished set up. Reach behind you, engage the cord and straighten your arm. The staff should come directly into your hand. It’s a completely one-arm operation. You should not have to pull the cord to you with your other hand. Adjust the cord length as necessary.