Fly fishing in lakes and reservoirs requires techniques that are different from angling in moving water. Just like learning how to manage a dead drift or shortlining a nymph through pocket water, they take some practice.

For novices, trolling around dragging a Woolly Bugger seems to be the only answer. It does catch fish — you’re covering water and offering a moving target to any passing trout. But how many other trout took a look at it and then decided, “This ain’t natural. I’ll dine elsewhere”?

The basic difference between moving water and stillwater fishing is obvious — in streams and rivers, the water provides the action, while in lakes and reservoirs, it’s up to the angler to make the fly imitate the natural. That covers a great range of action, all the way from letting a midge pattern sit quietly with just an occasional twitch to fast-stripping a streamer that imitates a minnow.

The more you know about whatever bug you are imitating, whether it be a caddisfly, mayfly, or damselfly, the better your technique. How do they behave?

Take damselflies, for instance. They’re one of the favorite fish foods on many lakes, including the ever-popular Lake Davis. Unlike mayflies and caddisflies, they must leave the water to hatch, so they have to make their way to shore (or something that is on the water, like a float tube) and crawl out before they can pop their shuck, spread their wings, and fly away. As a result, fishing from shore can be more productive than fishing from a watercraft during a damselfly hatch.

When damselflies are hatching, they tend to swim just under the surface, propelling themselves by wiggling their body back and forth, stopping occasionally to rest. They work hard at it, but actually don’t move that fast. So cast into deeper water and make a slow strip toward shore. And that is one of the keys to fishing damselfly nymphs: strip slowly. In fact, that’s an important key to stillwater fishing and the one most anglers tend to ignore. Really, you are almost always stripping too fast, unless you are pulling a streamer.

Taking all this into consideration, what’s the best technique for being successful during a damselfly hatch? First, you need a fly that has an extended body that moves as it is retrieved through the water. There are plenty of them on the market, but my personal preference is Jay Fair’s Wiggle-tail Damsel. Color is not as easy. Most damsels are greenish, but the green can cover the entire spectrum. They also can be light brown. On Davis, damsels will start out green in the early part of the day and then get darker and turn brownish as the day wears on. Imitations don’t need to be weighted, because there usually is no need to fish them deep. A floating line works just fine.

As already noted, damselfly nymphs will be trying to get to shore, so wading, rather than float tubing, when possible, is the way to go. The nymphs also tend to move with the wind, so if you have a choice — such as fishing on a spit of land — cast into the wind. Strip slowly, with regular pauses. One technique is to twist the line back and forth over your thumb and little finger. It makes for a slow, very steady retrieve and keeps slack line off the water. Don’t forget to pause, because that’s an invitation for the trout to slurp up dinner.

Other Hatches

What you learned about stripping damsels also holds true for other trout foods, such as mayflies and caddisflies. The major difference is that mayfly nymphs and caddis pupa move to the top of the water to hatch, rather than make their way to shore. For the most part, they wiggle upward through the water column, then sink back down a ways when they rest. Logically, a sink-tip line or a long leader to imitate this upward motion would work best, and either can be effective if you know where the trout are feeding.

But the reality is that much of your time on still waters is spent searching for trout, which often hold at a certain depth that depends on temperature and food, so a full sinking line that keeps a fly at one level is more effective in finding them. With a full sinking line, you can count down each cast so that any action can be duplicated if you get a strike.

Although most of your stillwater fishing will be under the water’s surface, when there is a hatch, trout will key on the emerging fly. If you do find a hatch, the trick is, whenever possible, to target a specific fish. Remember, the bugs are for the most part moving toward the surface, so the fish need to move around to pick them off. Most of the time, trout cruise in a specific pattern, often a circle or an oval, and if you can determine that pattern, or in what direction they are heading, you can put your fly in front of them, instead of where they were a few seconds before. And, yes, spotting this pattern takes some practice, but is well worth the time — it is a great way to catch big fish.

Also, big fish don’t usually make big splashes or commotions as they take these flies — they just suck them in, so don’t pass up a dimple in the water because you think it is a small trout.

An exception to this slurping rule is the annual Hex hatch, when the largest of mayflies, Hexagenia limbata, do their thing. Lake Almanor is famous for its Hex hatch, which begins in mid-June and lasts for about a month. It occurs in the evening, during about a 45-minute period from the time the sun sets until darkness is complete. Big trout just smash these two-inch yellow mayflies as they reach the surface, break out of their shucks, and prepare to fly away. Seeing five-pound trout come all the way out of the water after a fly is an adrenalin-pumping experience.

And, yes, I’ve actually seen big trout come out of the water to pick off a Hex that already is in the air.

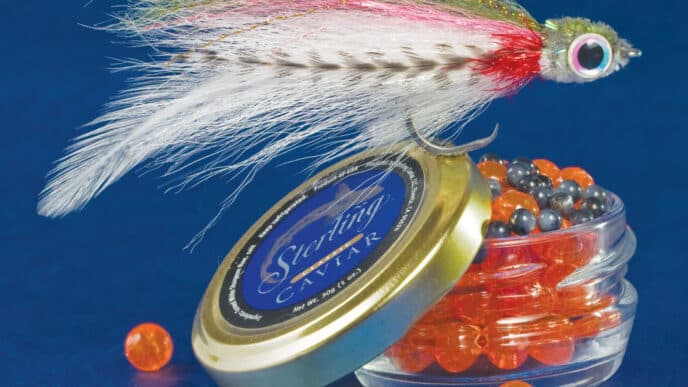

At the other end of the spectrum is fishing midges. It can be like watching grass grow, but is an extremely effective technique. Midges hatch year-round, so during the winter, they are about the only choice for dry-fly angling.

Most midges are small, down to size 20 and 22, although some range as big as a 14. When they hatch, they very slowly make their way to the surface, where, because of their small size, they can have trouble breaking through the surface film. Fishing imitations in the film, or just under, is the best way to go. Except for perhaps a gentle twitch every now and again, just let your fly sit and wait. And wait and wait and wait. Fish need a lot of them to make a meal, and at some point, they’ll get around to yours. Trout sip midges gently, so set the hook at any movement. My eyesight isn’t good, and to offset this, I usually put the midge as a dropper from a larger dry fly that I can see clearly.

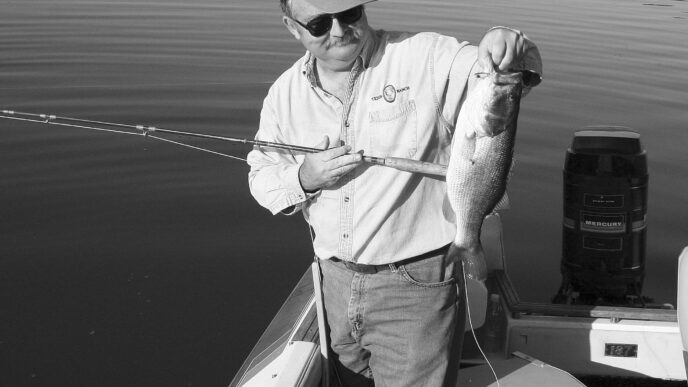

Fishing Streamers

When you get tired of fishing midges or stripping slowly, there’s always the possibility of hooking a big fish with a streamer. These minnow imitations can trigger a vicious strike from larger fish, but it usually is a case of a lot of work and few fish. Strip as quickly as you can — those little fish stay alive by moving fast. One way to achieve speed is by holding the rod under your armpit and stripping with both hands. Be sure to use a heavy leader, because there aren’t going to be any gentle takes.

A good place for streamer fishing can be Lake Crowley. Sacramento perch are a favorite food for Crowley’s big trout and streamer imitations can be deadly when the small perch are seeking cover in or near weed beds along the shoreline. The Hornberg Special has long done well as an imitation, but local tyers have developed many other patterns that imitate perch minnows. In putting all these techniques together, the effective angler should make every cast count. If you are using a sinking line, don’t just toss it out and wait for a bite before you start stripping. Know how quickly that particular line sinks and count it down. That’s the only way you’ll be able to duplicate your success if you get a strike or a fish. If you’re not getting hits, change your technique before you change your fly. Try it deeper or slower, before you switch to something else, particularly if you are using such all-purpose nymphs as a Hare’s Ear, Pheasant Tail, Prince, or Bird’s Nest. And above all, except when you’re fishing streamers, on lakes and reservoirs, remember to strip sloooooowly.

When Fighting a Fish…

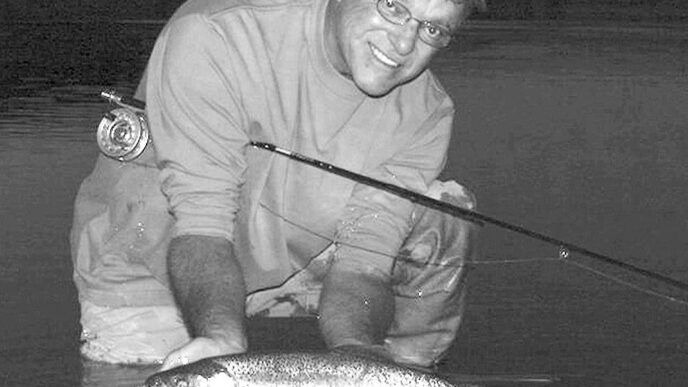

A word about playing and releasing big trout caught in still waters. You need to get them in fairly fast, so keep the pressure on them. First, don’t go light with a rod — a 5-weight or 6-weight is fine. Lighter means you’ll have a longer battle getting a big one to the net. I like a rod with a fairly soft tip, but with a solid butt section so I can really put pressure on the fish.

Second, whenever possible, use a heavy tippet, 4X or heavier. In some cases, this won’t be possible, but usually, fishing under the surface, as you’ll mostly be doing, allows you to use a heavier tippet without spooking the fish.

Once you have a big trout hooked, play it hard. If it’s not taking line, you should be trying to get it in. Once it’s to the net, make as quick a release as possible, preferably without taking the fish out of the water.

There’s a reason for this. Trout build up lactose during the fight, and if there is too much of a build-up, it kills them. They may seem revived and swim away, but actually can die minutes or even hours later. So get them in fast and make sure they are completely functional before letting them go.

Bill Sunderland