Mention the word “sharks,” and regardless of the medium or the format, you have a captive audience. The intensity of interest is due primarily to their role as predator and their penchant for attacking and consuming other creatures, in some cases, humans. In more than half a century of saltwater fishing in many parts of the globe, I’ve had many encounters with sharks, and fortunately, in most cases, I never felt that I was next in the food chain. This is mainly due to the fact that I was fishing from seaworthy boats that afforded a fairly substantial margin of safety.

An exception to this was when I used to fish the Caribbean side of Costa Rica at the late Bill Barnes’s Casa Mar Lodge. Back in the 1980s, this area was rife with bull sharks, and it was not uncommon to see 100-pound-plus tarpon bolting up into the air with large sections of their torso ripped away. The boats we fished from were 16-foot aluminum johnboats with only inches of freeboard, large bull sharks would even attack tarpon that were in the process of being released, pinning them to the gunwale. Dramatic stuff indeed, but to my knowledge, no one was ever injured.

The danger level of course escalates when you enter the shark’s environment and venture into the water. On the face of it, the prospect of deliberately wading into an area frequented by sharks with the intent of trying to fish for them with rod and reel seems like pure madness. However, I must confess I was persuaded to do this on my first trip to Key West back in the early 1970s. We waded into knee-deep water and cast streamers to cruising lemon sharks. When you managed to get one to take the fly, the experience was exhilarating, and any concern for the danger quickly evaporated. At the conclusion of the struggle, you simply held the reel spool stationary, pointed the rod straight ahead, and popped the tippet. The shark simply swam away.

Of course, wading for sharks is not for everyone, and if you’re fishing along the California coast, the opportunity to do so is extremely limited. One of the few times I did so was years ago, when I tried wading for leopard sharks along San Diego’s beaches — something I plan to do more of in the future. But the fact remains that for the majority of locales, the most productive angling approach is offshore from a boat, something I began doing on a regular basis back in the early 1970s when I lived in Redondo Beach. With a steady teaching income, I was able to purchase the boat of my dreams, a 20-foot SeaCraft.

Chumming

I fly-fished for sharks when I lived in the Northeast, too, but my interest really peaked when I first met Dan Blanton in the early 1970s on a group outing he made with members of the San Jose Fly Casters to Redondo’s King Harbor. At the time, the harbor was home to what only can be described as an incredible bonito fishery. Dan told me about the trips he was making to Monterey Bay to fish for blue sharks along with early pioneers such as the late Myron Gregory (a fly-casting champion), Larry Summers, and Bob Edgely. These Northern California fly fishers perfected a chumming technique similar to what I learned back east, and it worked so well in the waters around Catalina Island that I could practically guarantee I would encounter sharks on any given trip. The technique basically consisted of using frozen blocks of ground-up fish with high oil content, such as anchovies, mackerel, and sardines, suspending it just under the water’s surface, creating an enticing slick as the boat drifted along in the current. Today, you can save all the trouble of preparing this yourself and purchase bags of frozen chum.

The effect was like kids and ice cream on a hot summer day. The sharks swam right to the source in droves. The sharks were mostly blues, and it was not uncommon to have as many as 10 to 12 sleek critters swimming around the boat, ready to clamp their jaws on just about anything you put in front of them. One day when I was out alone, I dozed off in the warm afternoon sun as the boat bobbed on the gentle swells about 15 miles southwest of the Point Vincente lighthouse. I was jolted awake by a sound and shaking motion that at first caused me think I may have drifted over a rock or some other type of structure. Realizing there was nothing of the sort in these waters, I peered over both sides of the boat near the bow and didn’t see anything, but when I went to the stern and looked down, I saw a very large blue shark mouthing the stainless steel prop on one my outboards. Most blues averaged somewhere in the range of 30 to 50 pounds, but this brute was considerably larger, and instead of the chum bag, it was attracted to the shiny, bright props.

In those early days, I always fished according to IGFA standards, which meant you were permitted to use only a 12-inch bite tippet — in this case, 60-pound-test single-strand wire. I hooked this shark on six different attempts, and each time, I was broken off when the mono portion of the tippet rubbed against its hide. I know of no other species that is so persistent in its feeding habits that you can repeatedly plant a hook in its jaw and it comes back for more. Many in the bait-fishing fraternity tend to denigrate blue sharks, but when you target them on fly gear, their sporting qualities are maximized. Tackle one in the 30-pound plus class on a 10-weight, and you will have your hands full.

Mako Sharks

It seems to be the norm that as one progresses in any sport, the quest is to seek greater challenges. In the case of fly fishing for sharks, a natural progression is to jump from blues to makos. The excitement quotient is raised significantly, a fact that Zane Grey no doubt had in mind when he referred to them as the “aristocrat of sharks.” In contrast to the blue, which spends a good deal of time scavenging, makos are high-speed predators. Marine scientists have clocked them at speeds approaching the 50-mile-per-hour mark, a velocity that enables them to pursue healthy tuna. The size of their gill slits is an indication that they are designed for high-speed predation, and their habit of suddenly showing up in a chum slick gives you a clue that they are fast-moving ocean roamers. Blue sharks tend to slowly work their way into the slick, and typically the first sign of their presence is their dorsal fins, which are visible as they weave their way toward the boat. In contrast, makos often appear suddenly, and even to those with little shark experience, they are readily distinguishable from blue sharks. The latter have a much sleeker body profile. Makos are more fully rounded, similar to their close cousin the great white shark. In some areas, makos are referred to as “mackerel” or “bonito sharks,” which is attributed to the fact that their diet often includes members of the tuna family.

An area referred to as the California Bight consists of deep offshore canyons approximately 20 to 100 miles long, originating from the Mexican border north to Point Dume, and this region apparently serves as a nursery for makos. Female makos typically give birth to two to six pups that weigh about five pounds, and they are fully equipped to fend for themselves right out of the box. Makos off the Northeast coast commonly top the 100-pound mark, but most of the ones we encounter in Southern California tend to run from 20 to 80 pounds, which is ideal for fly gear. The fact that with the exception of striped marlin and dorados, they are about the only game fish in Southland waters that will go airborne when hooked puts them on the wish list of most bluewater fly anglers.

When and How to Fish for Sharks

In Southern California waters, the optimum time to target makos generally is from May through October. The best two months are normally July and August. The number of blue sharks in Southern California waters seems to have diminished somewhat, but the mako population looks to be in relatively good shape. Thus, not only are chances high that you will encounter mako sharks on a given outing, but the nature of the fishery is such that even novice fly fishers can easily get in on the action.

The simple reason for this is that when sharks are being drawn right to the boat, you really do not have to know how to cast. Like it or not, at least where saltwater fly fishing is concerned, the major challenge for novices is casting proficiency. But the blue or the mako is being drawn to the source of the chum, which is right at the boat, so often all that is required is simply to flop the fly into the water. It is in the hook-setting and fish-fighting phases when the inexperienced fly fisher will require coaching.

Since the shark’s jaw is studded with teeth, the best hook placement is in the fleshy part of its mouth. As with the technique used for saltwater species such as billfish and tarpon, the angler should resist the temptation to try and set the hook as soon as the shark takes the fly. Instead, it’s best to hesitate until it makes a turn with the fly in its jaw, then make a strip strike by simultaneously pulling back on the fly line and sweeping the rod low and sideways. With makos, the fun really begins when it scorches out away from the boat and lights up your emotional circuits with some aerial acrobatics.

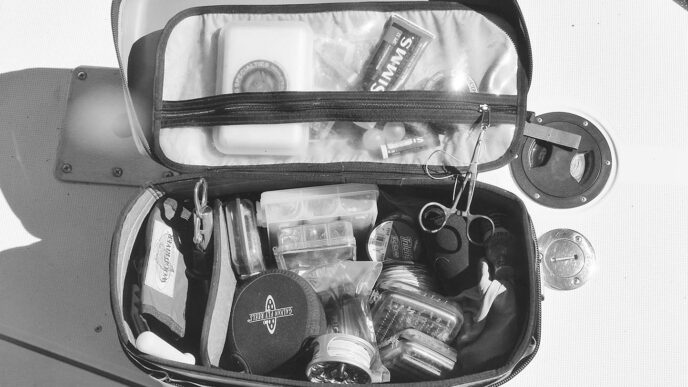

The tackle setup for this fishing is relatively simple. Obviously, you’ll want a rod-and-reel combination capable of withstanding the shark’s fighting prowess. Fly rods in the 10-weight to 12-weight class, coupled with reels sporting smooth drags and at least 250-yards-plus of backing capacity, will cover most conditions.The newer gel-spun and braided lines for backing have garnered a lot of praise. I use them, but I also fill some of my reels with Dacron backing (I prefer at least 50-pound test for this fishing) and never have a problem.

Since the sharks are drawn to the chum on the surface, I recommend floating fly lines, either in full or shooting-head configuration. Slow-sinking intermediate lines will also work. If you are new to this game and want to stand a good chance of bringing the shark to the boat for photos, I suggest you forego the IFGA’s leader standards. The shark’s skin is a continuation of its dentition and very abrasive. Blues are especially notorious for a violent twisting action, and if a fish starts rubbing against the mono section of the leader, it will quickly part. To help offset this, use something like a 3-foot length of 60-pound-test butt section and about 2-1/2 feet of single strand wire attached directly to the fly. The longer wire leader also makes hook removal easier. Where feasible, this is accomplished by using a three-foot metal rod to dislodge the fly.

Flies for sharks can be very simple concoctions. The chum is what draws them in, and as evidenced by many examinations of their stomach contents, typically, sharks are not highly selective about what they chose to chomp down on. Basic hackle streamers (I don’t use premium hackles for this) in bright colors such as orange, yellow, and red will draw strikes. I feel I get the most solid hookups with size 3/0 hooks. Poppers will also work, but it can be more challenging to get a good hook set.

If you don’t have access to a seaworthy boat, there are some San Diego–based charter operations that I can recommend. One I can personally vouch for is Captain Scott Leon’s Paradigm Shift Charters, (619) 400-9521. Scott is a former Navy Seal who trained in these waters and has an intimate knowledge of practically everything that swims there. Conway Bowman has done more than anyone to popularize fly fishing makos in San Diego, and his Bluewater Guides and Outfitters service can be reached at (619) 822MAKO. Conway also mentored Captain Dave Trimble, who has logged considerable experience with this fishery and is one of the skippers in On the Fly Fishing Charters, (928) 380-4504.

Regardless of your fly-fishing experience, this is an exciting game, because everything is in plain view from the moment the shark is first sighted to when it opens its jaws to devour your fly. There’s also that eerie realization you sense with no other species of fish that given the right circumstances, what just ate your fly would also eat you.