Every year or so, this fine magazine prints an article on how to fly fish the surf. These informative pieces are written by folks who clearly know what they are talking about, and the articles represent a great starting point for anyone interested in dipping their toes and flies in salt water. Intrigued, many people try the surf a couple of times and find it’s simply not their cup of tea. Some get lightly hooked and time their fishing trips so they can wet a line when the Web sites or local rags say the fish are running. A few wayward souls discover they actually belong in the surf and devote as much time as they can to splashing through the suds. The following is for anyone who suspects they may be in the last category.

If It’s Wet, Fish It

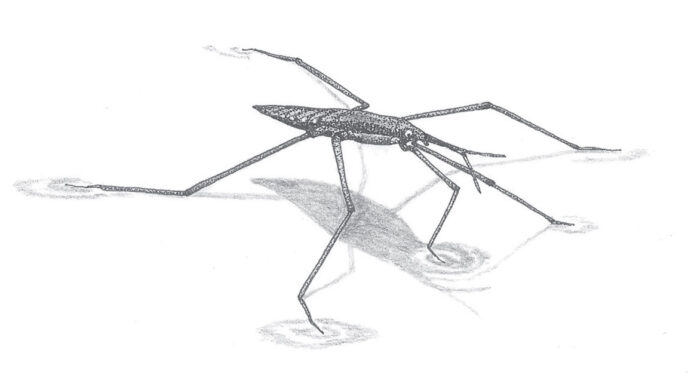

During a fly-fishing club presentation, someone asked me if there was any part of the beach I wouldn’t fish. Glibly, I replied, “Dry sand, and I’m not even sure about that.” Perhaps the most important thing any fly fisher needs to know and remember is that fish (just like any other hungry animal) will generally go where the food is. In the surf, the constantly changing tide and waves create a moving feast. At one stage of a tide, the fish may be found at the head of a trough, pigging out on soft-shell sand crabs. Ten minutes later, they may have finned over to the edge of an adjacent flat where nickel-sized Dungeness crabs are being rolled off the sand by fast-moving tables of water. Wait another 10 minutes, and the fish have slipped into the nearby rip, where they ride strong currents and pick off protein-rich worms or sand crabs heavy with high-calorie roe. The action may last for another 15 minutes before the fish decide to exit the rip and move 100 yards down the beach in search of fresh fare. Clearly, staking out a spot and fishing it like a metronome is not going to be too successful under these circumstances.

Rips, Flats, and Troughs

New and infrequent surf fly fishers often fish the same water as the bait-fishing folks. Bait guys usually camp out at the top of so-called “holes” and let the steady stream of body fluids oozing out of their bait bring the fish to their hooks. Being a clean-cut fly fisher, you have eschewed the use of bait and have dedicated yourself to the art of fishing with fluff, feathers, and sparkly synthetic stuff. Since none of this smells like food, fish won’t beat a path to your hook. Like a traveling salesman, you will have to go to where they are.

By all means, start with holes, which are actually rips and are easy to spot. If you don’t know what they look like, simply find some bait fishers. You will notice that the water in front of them looks slightly darker and less foamy. That’s the rip.

There are two other places you need to be able to locate amid the heaving waves and sluicing currents. Flats are relatively shallow areas and are usually betrayed by the large areas of foam they generate. In low-light conditions, fish will move up onto flats to feed. Jacksmelt seem especially fond of flats, and I have caught quite a few striped bass on them, too. Fish hooked on flats tend to make long runs toward deeper water, which certainly increases the fun factor. Jacksmelt fight like a bonefish-trout hybrid, with an initial fast run, followed by a series of rapid zigzag moves. Stripers tend to make the water explode prior to hitting the afterburners for Hawaii.

Troughs are deeper waters that run parallel to the shore. They look and behave like rivers and should be fished accordingly. Start by working the headwaters and then attack the near and far banks. Cuts in offshore bars will often dump water into troughs, so make sure you pay attention to line tension (more on this later) as you work the far bank. These cuts may be only a few inches deep, but they provide fish with safe entry and exit points for the trough, as well as an additional side stream of food-bearing currents.

Location, Location, Location

On countless occasions, I have seen anglers fishing within a rod’s length of each other, yet experiencing dramatically different catch rates. Both appear to be working the same water, but clearly, something different is going on beneath the waves. It may be hard to believe that a few feet can make any difference in a body of water with a surface area of 64 million square miles, but it often does. The one theory I have heard that best seems to explain this phenomenon is that the fish form a narrow school (like a queue) along some sort of structure, such as a sandbar or current seam. This school may be only a fish or two wide, and they won’t move far to intercept prey or your flies. When this is happens, the angler in the hot spot will get grab after grab, while someone just six feet away will get nothing. To complicate things further, currents in the surf can be fickle, constantly reacting to changes in pressure from waves, the tide, and even movements of sand. This means that a hot spot may be hot for only a few minutes. If you think a piece of water should hold fish, but all it offers is untouched retrieves, try moving a few feet and directing your casts in a fan pattern. This will alter the path your fly takes as it is retrieved and may be all you need to get in the groove. Or you can up your game a notch or two by concentrating on what your fingers are telling you about the underwater realm.

Tactile Enhancements

For most folks, a fly line is something that conveys a fly toward fish and then brings them to hand once they are hooked. In the surf, a fly line provides an additional benefit — it can tell you a lot about currents. Understanding currents is what separates the beginner/intermediate surf-zone fly fisher from the expert. Not surprisingly for a place with such heavy hydraulics, the surf is full of currents. But just because the water on top is moving one way doesn’t mean that the same thing is happening a few feet down. In order to understand what is going on below the surface, you need to concentrate on the tension in the line as it crosses your fingers.

This is where magic happens. Instead of simply dragging your fly through an invisible world, you can adjust your casts and retrieves to place your fly in prime water and move it in a way that will get the attention of the fish.

Faster currents increase line tension, while slow currents, you guessed it, reduce line tension. The degree to which currents affect tension depends on their strength, the angle of the line relative to the current, and how much of the line is subject to the current. You use this knowledge to create a mental 3-D map of the underwater currents in front of you.

If this sounds intimidating, don’t worry. It’s less complicated than it sounds. Like any form of fly fishing, this skill can take a few trips to develop fully. Be patient. Start by making short, 30-foot casts to obvious spots and feeling how the line responds. Once you have an idea of what is happening close in, send the next set of casts out about 40 to 50 feet and repeat the line-tension analysis. This may be all the distance you need to reach fish. If not, your final set of casts should be sent out as far as you can manage. Beyond 50 feet, it can be difficult telling exactly what is going on, since the fly line may be cutting through several different currents.

When you have completed your survey, you need to stitch the information together. Most of the time, things are pretty straightforward. In troughs, currents typically run parallel to the shoreline as they head toward the nearest rip. Once they hit the rip, they change direction and head offshore. Water flushing off a flat or offshore sandbar can be more complicated. Subtle changes in the topography of the sand will create areas with strong and weaker currents. Occasionally, your line will uncover weird little countercurrents or side currents. I find this happens more often when a beach is subject to swells from the south, which tend to reverse the hydraulics of most beaches.

Armed with a mental current map, fly fishing the surf goes from being chuck and chance to an almost surgical dissection of the water. Now, instead of simply casting the fly out and dragging it back, you cast to specific spots and strip or slip line as the tension on the line dictates. You can make the fly do all sorts of cool things, such as tumbling over a flat, dropping through the water behind a breaking wave, or twitching along the edge of a rip. Not only does this usually result in more fish, it also makes the fishing far more interesting.

Flies

Unlike fussy spring-creek trout, surf zone fish are seldom discriminating when it comes to flies. With the constant pounding of waves and strong currents, the energy needs of surf fish are very high. This means they don’t have a lot of time to check if your fly has the right number of appendages or eyes. If a fish can see it and it will fit in its mouth, it will usually chase it down and eat it. This makes fly selection a fairly simple two-part process.

First you need to consider visibility. Areas where currents are causing erosion of the sand are a magnet for fish. Unfortunately, the cloudy, sand-filled water limits visibility. Under these circumstances, a red fly often seems to be more effective. It is possible this is because red materials reflect more near-infrared light, which many species of fish can see, but humans can’t. Near-infrared light is transmitted through cloudy, sand-filled water much better than any other color. For most other situations, an orange fly seems to be the way to go. I suspect this is because sand crab roe is orange, and surf-zone fish key in on cholesterol-rich crab roe the same way we can’t resist fast food. Sometimes, sand crabs or other invertebrates aren’t the main course on the surf menu. Baitfish such as anchovies, sardines, surf smelt, grunions, and baby perch can be an important food source for surf-zone species. There are plenty of cool baitfish patterns out there, but in all honesty, a small selection of Deceivers and Clousers in white or chartreuse will usually cover the bases.

The second consideration is weight. Try to use the lightest fly you can. This will make casting easier and allow the fly to swim more naturally with the currents. I typically carry a selection of flies, including patterns with no weight, with beadchain eyes, and with lead eyes. I have even tied up some flies with foam, which enables me to work skinny water without having the hook point constantly plowing through the sand.

Lines

Because of their ease of use, most surf fly fishers use high-density integrated heads in the surf. These lines get the fly down quickly and work in both deep and shallow waters. They catch plenty of fish. However, unless the surf is particularly boisterous, I find this to be a rather clunky way to angle. Like fishing worms under a bobber or chunks of squid behind a pyramid sinker, the technique eventually becomes rather dull and repetitive. Most integrated heads aren’t particularly sensitive, and it can be tough feeling what is going on with the line and fly as they work through the water. This reduces your ability to feel currents. Use a less dense line, and your fly will be far more responsive to the currents.

I tend to use HiD-type shooting heads (for example, Scientific Anglers Type V or Cortland Type 6) for most of my surf fly fishing. They sink around five inches per second in salt water, which is just about perfect when teamed with unleaded flies. If the current is faster in the area I want to fish, I compensate by casting a bit farther upcurrent, which gives the fly time to get a bit deeper. If that doesn’t work, I simply switch to a bead-chain or lead-eyed fly. When the waves get below three feet, I switch to an intermediate head. With this setup and a selection of lightly weighted flies, I can work shallow flats and deep troughs. Using shooting heads allows me to change lines quickly without having to carry a spare spool or reel. But an extra spool is not a huge burden, so by all means, use full lines, if you find shooting heads a challenge.

Different Gear

One of the really cool things about fishing the surf is that you can use a variety of tackle to catch fish. Over the years, I have experimented with everything from dinky little 7-foot sticks and double-taper 3-weight lines to 12-foot double-handers with spinning reels and ballistic T14 shooting heads. Others have played around with unique setups, too. Mark Won, who fishes the surf more than anyone I know, has become intimidatingly good with a double-handed rod. Many folks who fish the surf with double-handers use fast-sinking shooting heads. Not Mark. He has matched his double-hander with a floating Skagit head and a length of T14 tungsten line. This is basically a surf version of the MOW rig many anglers use for steelhead. The businesses end of Mark’s rig involves three flies and a leader made from tangle-free 50-pound-test mono. It may not be the most delicate of setups, but there is no denying its ruthless efficiency.

While fly fishing the West Coast surf isn’t exactly new, it is still far from well understood. This means we still have new frontiers to explore. For example, there are a number of fish in the California surf that have not been consistently taken on flies. Leopard sharks and bat rays are fairly common surf-zone predators with a penchant for crabs, yet no one I know has figured out how to take them reliably on flies. An adult bat ray can weigh up to 200 pounds. That is big-game fishing, and it’s available right on our doorstep. Someone is going to figure this out, and when they do, I bet it will involve a 12-weight and a lot of heavy backing. Maybe it will be you.