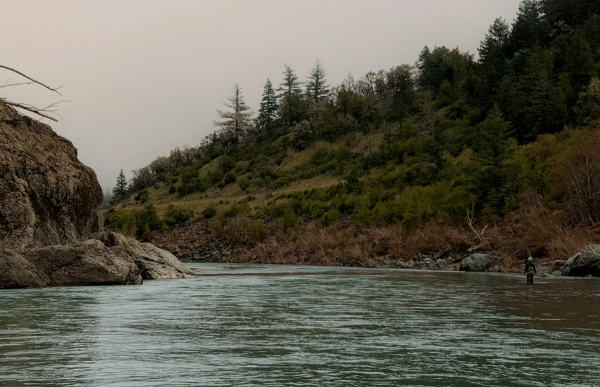

The sun was gone, but it was summer, and there would be ample light to fish for another hour. My two friends and I had fished all day in the little freestone river, catching great numbers of spunky rainbows in the 10 to 13-inch range…almost all on 3-weights and dry flies, fishing likely pockets and riffles. Pleasantly worn out, we sat together on the graveled bank, talking softly and watching the pool before us. Tired as we were, we all saw the rise on the far bank at the same moment, and our fatigue instantly vanished in a chorus of exclamations. The subtle bulge that gently pushed water against the grassy bank clearly did not belong to a foot-long fish. We watched in rapt attention as the fish rose again, and then again. There was no perceptible rhythm in its feeding, as is often the case early in a hatch when the bugs are still spotty—the fish was simply rising to what the river gave.

One of my friends, fairly new to the sport, was literally shaking with excitement at the prospect of casting to what was obviously a very significant fish for such small water. My other friend and I agreed he should get the shot, and we prepared him for the presentation—lengthening his tippet to help achieve a drag-free float and choosing a tiny emerger to match the little Pale Morning Duns we guessed were hatching. Properly prepared, he crouched and carefully approached the stream, positioning himself slightly upstream of the riser as we instructed. Kneeling in just inches of water, he stripped out some line, then went completely still, waiting, staring heron-like at the spot where the trout had risen. Nearly five minutes passed, and just as we were thinking we had somehow spooked the fish, it showed again, this time flaunting more of its impressive jaws. Our friend immediately began false casting, then laid out a beautiful, tight-looped cast. My other friend and I glanced at each other and winced, but didn’t say anything. Another rise, and another cast, and a perfect dead-drift presentation. And again, and yet again. The big beast was not spooked and continued to feed, now even more regularly as the hatch intensified. Frustrated, our friend whispered, “Should I change flies?”

“Nope,” we answered, “That isn’t going to help.”

“Then what?!” he pleaded. “What am I doing wrong?”

“You tell him,” my friend said.

“Well, the problem is not your casting—I couldn’t do better myself. And your dead-drift presentation is flawless, just perfect.”

“So why isn’t this fish eating?!” he asked, his attention distracted as the fish made a particularly showy rise.

“That fish has not yet seen your fly. Every cast has landed a good foot below where the fish is suspended. You are seeing the rise, then casting to the rings from the rise form. But by the time your brain registers the rise, the current has carried the rings 6-12 inches downstream. The secret with a consistent riser like this is to not cast until you have marked the rises.”

“Marked them?” he asked. “What does that mean?”

“Whenever you see a fish rise, the very first thing you want to do is mark its location against something behind it—usually a stick or unique clump of grass on the far back, that sort of thing. Or if the fish is in the middle of a large river, it could be a tree on the opposite bank…not perfect, but far better than just casting to the area and hoping for the best.”

He looked across the stream again, and when the fish rose, I saw his eyes squint in concentration. “Okay, got it,” he said, more to himself than to me. He let the fish show itself once more, nodded almost imperceptibly, and made a cast.

The big brown rose confidently and inhaled the little dry fly. To his credit, our friend waited for the big head to slip back beneath the water before coming tight. For a moment, nothing, just tightness…then chaos as the fish realized something terribly wrong had just happened. Minutes later, the magnificent trout slipped into the shallows, where it lay patiently as we snapped a few pictures. Our friend dislodged the hook and held the fish upright for only a few moments before it pushed from his grasp, swimming leisurely back toward the far bank. Looking up, shaking even more violently than before and with a smile of pure joy on his face, he murmured, “Marking,” shaking his head in wonder. Then, looking across the stream, he pointed out a single strand of long grass that hung out over the water, the tip of it mere inches above the water. “That is the biggest fish I’ve ever caught, and that piece of grass is what made it happen. Unbelievable.”

This is a scenario I have seen play out countless times in a variety of circumstances. The truth is that most consistently rising trout are highly catchable, even in tough spring-creek situations. Yes, you need to select the correct fly and make an accurate, drag-free presentation. Yet if you are casting to the rings of the rise, you will often be casting right on the fish’s head or just behind it, both of which are equally ineffective. As my friend discovered, the key is to take the time to allow the fish to rise several times and “mark” the rise form against something solid in the landscape behind it. You can then cast a few feet above where the fish actually is, allowing the fly to land well upstream of the riser and drift naturally into its line of sight, giving yourself a great chance for success.