The last time I was trout fishing up in the Sierra Nevada, I found myself thinking about Kenneth Rexroth, our great poet of eros and nature. Rexroth was most at home in these mountains, and he wrote nearly all his poetry in the high country. He broke ground for what famously became known as “the bear-shit-on-the-trail school of poetry.” An academic dullard back East had meant that as a putdown, but Rexroth took it as a compliment. After all, he was quite the outdoorsman, surely the only major poet ever to have sex in a canoe. (See his poem “Floating.”) So it came as no surprise to me to learn that he was also handy with a fly rod. Rexroth was a Zen adept who preferred dry-fly fishing above all other angling methods. He regarded fishing with a dry fly as “a higher form of mathematics, practically embodied, of the free flow of moving water. It combines all of the virtues and none of the strains and responsibilities of both art and mysticism. Besides, you catch fish.” (“The Tao of Fishing,” San Francisco Examiner, 1960)

Back at his mountain camp, presumably after cleaning the fish, the poet would contemplate the infinite. For nigh on thirty years, he did most of what he called his “creative work” — as distinguished from his journalism — while camped in these mountains. Seamus Heaney has said that “poetry is most itself when most at home,” and the Sierra Nevada was Rexroth’s spiritual dwelling place.

Kenneth Rexroth was the Father of the Beats, a title he never cared for. “An entomologist is not a bug,” he explained. Rexroth was the most prominent figure in what came to be known as the San Francisco Renaissance. For many years, on Friday nights, his home out in the fog belt flourished as a literary salon for painters, political radicals, freethinkers, and poets. Rexroth introduced Jack Kerouac to a young Gary Snyder and was among the first to promote the writings of the Beats (although he thought Kerouac an idiot). He emceed the legendary poetry reading at the Six Gallery on Fillmore Street when Allen Ginsberg read from his poem “Howl,” changing the course of modern American poetry, seemingly overnight.

Rexroth came to San Francisco in 1927, after a disastrous childhood in which he lost both parents, after hitchhiking across the Western United States as a teenager, and fresh from working on Forest Service trail crews and in cowboy camps as a packer, wrangler, and cook. He was a full blown hipster by the time he arrived, but mad for the outdoors.

The Federal Writers Project, a New Deal program set up to help out-of-work authors, got him up into the Sierra. He wrote a guidebook on camping in the mountains for the Works Progress Administration. (It was never published, but is available online.) His knowledge of the subject was encyclopedic: everything from how to pack horses to how to fashion emergency lean-tos and bedding from pine boughs. There is even a brief entry on the flies he used to fool Sierra trout. He preferred Professors and Parmachene Belles.

Rexroth made his home in San Francisco, where he hustled a living as a poet and a literary journalist. But each August, for many years, he would escape the city to go to the Sierra and tent out, often for months at a time. Sometimes he would spend up to a third of a year, in late summer and early autumn, camped in the mountains. His need to experience nature up close was organic and fueled his creativity. He needed the outdoors, the hiking and fishing, as much as he needed poetry. Wordsworth said famously that poetry is emotion recollected in tranquility, and Rexroth said that he was at his most tranquil camped beside a Sierra lake at timberline. “I know plenty of places where there are beautiful lonely lakes, lots of fish, enough feed for the donkeys, and few or no people passing by all summer,” he wrote in one of his columns for the San Francisco Examiner. “For going on 30 years I have spent most of my summers this way.

. . . At least it is in the mountains that I write most of my poetry.”

Closer to home, Rexroth roamed the laurel and oak-shaded hills of Marin County directly across the bay from San Francisco. Marin was quite wild and lush back in those days, and his primitive writing cabin at Devil’s Gulch stands today as a landmark to the author. He combined a breadth of learning with a hungry attachment to the natural world. He was a true Renaissance man, as capable of writing an entry on literature for the Encyclopedia Britannica as he was authoring a camping guidebook or making love in a drifting canoe. He devoured the Eastern and Western literary canons and translated poems from six languages. A high-school dropout, largely self-taught, he made his living practicing literary jujitsu as a cultural or — as he called it — “intellectual journalist.” Only much later in his life, seeking some kind of financial security, did he finally accept a teaching post at a college. Rexroth published his criticism, essays, and reviews in whatever home he could find for his freelanced articles, and he wrote columns for various San Francisco newspapers. His work fills 54 books, and many of his columns and radio broadcasts still remain uncollected to this day. Described as a cosmopolitan looking at the wilderness, a man with a foot in both the Asian and Western traditions, and one of the first to write about deep ecology, Rexroth — as the poet Robert Hass has noted — “seems to have invented the culture of the West Coast.”

Rexroth was among the first Americans to translate the works of classical Asian poets. He showed a particular affinity for women poets, as well as for the writings of Tu Fu, the poet he most resembles. It is often noted that the landscape of the Pacific Northwest is similar in feeling to what is seen in Chinese inkbrush paintings and in those “pictures of the floating world” depicted in Japanese woodblock prints. So perhaps it was only natural for Rexroth to develop an attraction to haiku and Chinese classical verse.

His poetry looks out on nature, but is inward-bound. There are no snappy solutions, no slick solaces — rather, a calm, unblinking reckoning with the elemental difficulties of human life. One experiences many of the effects that are in haiku and Chinese nature poetry: a sense of an encircling stillness and a deep sense of the transience of things. Nature exists for itself, not merely as a symbol for some grand idea. And then there is that plain syntax: here is a poet speaking directly to the reader, not at or around him. Many of Rexroth’s poems describe the kind of sadness and melancholy that arises from a deep empathy with the fleeting beauty inherent in nature, human life, and art. The Japanese have a term for this sensibility in haiku . . . mono no aware, “the pathos of things.”

Eros and nature were the central and centering truths of his life. In his beautiful poem “ The Signature of All Things,” Rexroth, like the Christian mystic Jakob Boehme in the poem, “saw the world as streaming in the electrolysis of love.” For Rexroth, physical love was sacramental. He believed that physical love connects us to an awareness of the transcendent and is the key to realizing one’s true existence. If compassion was his moral philosophy, eros was his lodestone. Rexroth wrote some of the greatest love poems in our language, and his California mountain poems are among the best nature writing we have. The images in these poems shine like alpenglow on the mountains or the nimbus around a saint.

In his day, Rexroth was dismissed as a “regional poet” by many in the Eastern establishment. But like other “regionalists” closely associated with a particular place — Robert Frost in the New England woods, Wordsworth in the Lake District, or the Japanese haiku masters, who found the world in a single dewdrop — so deeply and passionately did Rexroth merge into the landscape of Northern California that he created a poetry that feels cosmic. One finds in these poems — in the words of his biographer Linda Hamalian — “a sense of a sacramental presence in all things.”

Like his poetry, Rexroth’s fly fishing also took on a deeply Oriental outlook. “Fly fishing is Taoism in simple and fascinating action,” he wrote in the San Francisco Examiner. “If you let it, it produces, and by natural methods, the same results, the crystal-clear calm of heart, that so many people seek by so much more difficult ways.”

Rexroth said in all seriousness that Izaak Walton was “the most Chinese of Western writers.” In The Compleat Angler, Walton’s characters pass their days on riverbanks reciting poems to one another — how Zen-like! In his essay on Walton’s masterpiece, in Classics Revisited, Rexroth noted: “Whoever wrote the little psalms of the Tao Te Ching believed that the long calm regard of moving water was one of the highest forms of prayer.” He assured his Examiner readers that fly fishing is Zen Buddhism without all the effort. He even considered using it “to pick up gullible chicks in espresso bars.”

“Many forms of sport are actually contemplative activity,” he wrote in his essay on Walton. “Countless men who would burst out laughing if presented with a popular vulgarization of Zen Buddhism, and would certainly find it utterly incomprehensible, practice the contemplative life by flowing water, rod in hand, at least for a few days each year. As the great mystics have said, they too know it is the illumination of these few days that gives meaning to the rest of their lives.” Like the grace notes in fly fishing, Rexroth’s best poems achieve a calmness of heart and mind that wasn’t always present in his troubled life and in his turbulent relationships with women. But in these poems, everything is illuminated and love and nature transcendent. The Complete Poems of Kenneth Rexroth won’t fit comfortably in your backpack — it’s 768 pages long — but take it to the Sierra anyway on your next fishing trip. This is a poetry that exalts what Rexroth, in one of his greatest poems, “Time Is the Mercy of Eternity,” called “the holiness of the real.” As his editor, Sam Hamill, said, “It remains to be explored, like a great snowcapped peak rising at the edge of the Pacific.”

CREDITS:

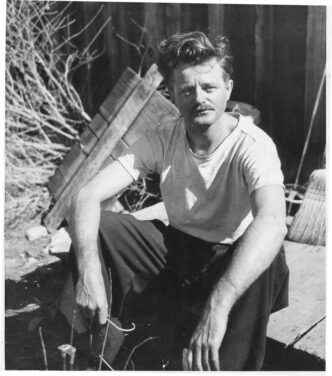

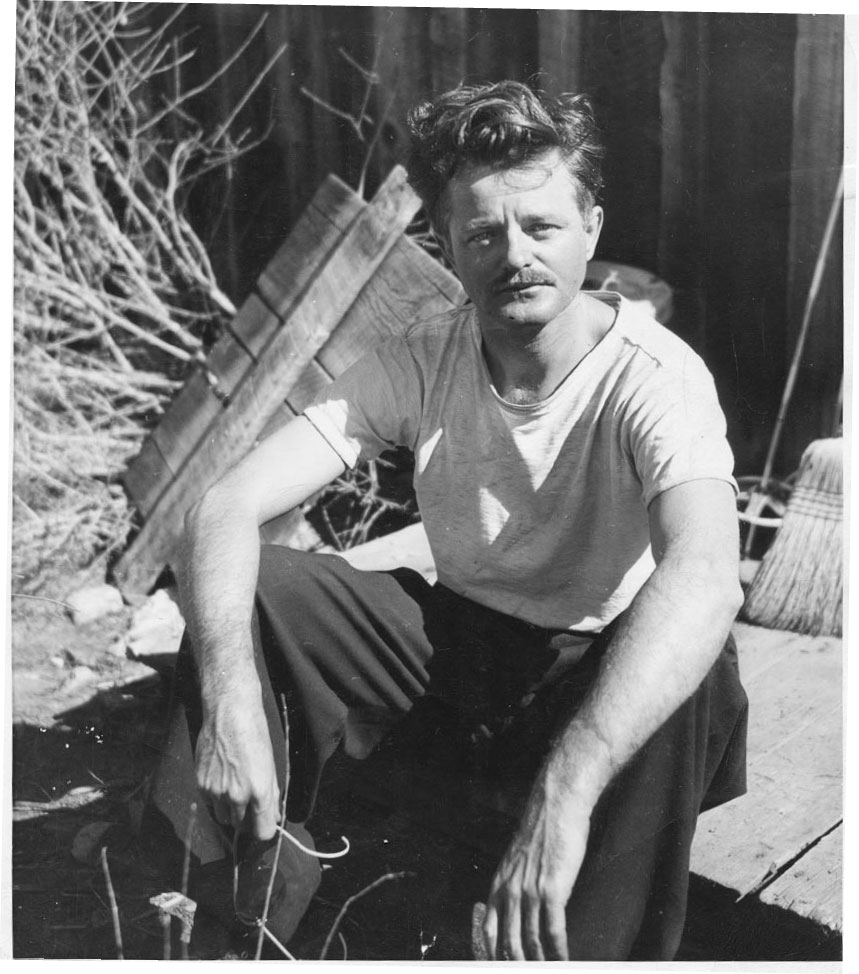

Photograph by Valerie Dauly-Smith, from World Outside the Window, copyright 1955 by Kenneth Rexroth. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

“Andree Rexroth (Died October, 1940),” by Kenneth Rexroth, from The Collected Shorter Poems, copyright 1944 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

“Time Spirals,” by Kenneth Rexroth, from The Collected Shorter Poems, copyright 1952 by Kenneth Rexroth. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Books by Kenneth Rexroth

The Complete Poems of Kenneth Rexroth, edited by Sam Hamill and Bradford Morrow (Copper Canyon Press, 2003)

The Collected Shorter Poems of Kenneth Rexroth (New Directions, 1966)

Classics Revisited (New Directions 1964, 1986)

More Classics Revisted (New Directions, 1989)

One Hundred Poems from the Chinese (New Directions, 1971)

One Hundred Poems from the Japanese (New Directions, 1955)

Camping in the Western Mountains (Unpublished, 1939; available online at hwww.bopsecrets.org/rexroth)

Andree Rexroth

Died October 1940

Now once more gray mottled buckeye branches

Explode their emerald stars,

And alders smolder in a rosy smoke

Of innumerable buds.

I know that spring again is splendid

As ever, the hidden thrush

As sweetly tongued, the sun as vital —

But these are the forest trails we walked together,

These paths, ten years together.

We thought the years would last forever.

They are gone now, the days

We thought would not come for us are here.

Bright trout poised in the current —

The raccoon’s track at the water’s edge —

A bittern booming in the distance —

Your ashes scattered on this mountain —

Moving seaward on this stream.

Time Spirals

Under the second moon the

Salmon come, up Tomales

Bay, up Papermill Creek, up

The narrow gorge to their spawning

Beds in Devil’s Gulch. Although

I expect them, I walk by the

Stream and hear them splashing and

Discover them each year with

A start.When they are frightened

They charge the shallows, their immense

Red and blue bodies thrashing

Out of the water over

The cobbles; undisturbed, they

Lie in pools. The struggling

Males poise and dart and recoil.

The females like quiet, pulsing

With birth. Soon all of them will

Be dead, their handsome bodies

Ragged and putrid, half the flesh

Battered away by their great

Lust. I sit for a long time

In the chilly sunlight by

The pool below my cabin

And think of my own life — so much

Wasted, so much lost, all the

Pain, all the deaths and dead ends,

So very little gained after

It all. Late in the night I

Come down for a drink. I hear

Them rushing at one another

In the dark. The surface of

The pool rocks. The half moon throbs

On the broken water. I

Touch the water. It is black,

Frosty. Frail blades of ice form

On the edges. In the cold

Night the stream flows away, out

Of the mountain, towards the bay,

Bound on its long recurrent

Cycle from the sky to the sea.