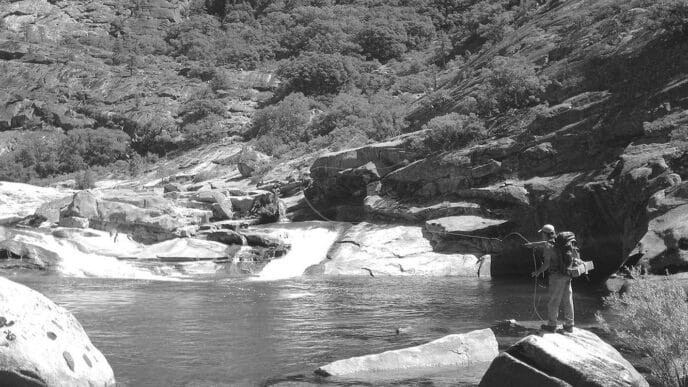

Ask a trout angler what line he or she is fishing these days, and it’s likely to be a 5-weight or lighter and probably a weight-forward taper. T’weren’t always the case. As recently as the mid-1960s, when fiberglass was busy supplanting bamboo as the dominant rod-building material, fly rods that handled 6-weight and 7-weight double-taper floating lines were the standard for trout fishing. Many rod companies — Winston, Orvis, Leonard, Powell, and Payne, among them — built bamboo rods for lighter lines, but they weren’t the norm. And if you wanted to fish a light-line fiberglass rod fifty years ago, your choices would have been severely limited.

Lines weren’t described by numbers back then, but by letters representing the diameters of their various sections. Those DT6s and DT7s would have been HDHs and HCHs. An HDH, according to the standard, had a belly of diameter “D” (.045 inches), tapered at either end to a tip of a thinner diameter “H” (.025 inches). An HCH would have a taper of from .050 inches to .025 inches. Of course, not everyone fished double-tapers. If you were a penny pincher or used a fly rod and fly line to fish worms or salmon eggs, you might have purchased a level “C” line. Or if you were one of the growing number of fly fishers who was looking for distance, you might have bought one of the new “torpedo” or weight-forward tapers, although doing so would have been more likely were you a salmon or saltwater angler, rather than a trout person.

The letter/diameter classification for fly lines was based on the notion that silk lines of similar diameters would perform similarly. But not all silk was identical, and some lines were tapered or treated in slightly different ways. And when manufacturers began to construct fly lines of braided nylon or braided Dacron or to give one braid or another a plastic coating, the performance variation between lines of similar diameters became more pronounced. The result was that you might need to try a couple of similarly lettered lines before you found one that you and your rod liked.

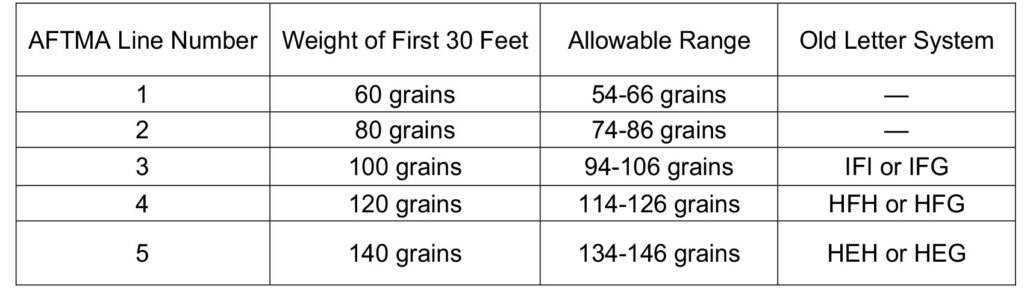

Enter the American Fishing Tackle Manufacturers’ Association (then AFTMA, now ASA — the American Sportfishing Association), which established the system, currently in place, that classifies fly lines by the weight in grains of the first 30 feet. In theory, the first 30 feet of, for example, every 6-weight line, no matter the taper, is going to weigh somewhere between 152 and 168 grains, with 160 grains being the standard.

But 6-weight lines are no longer the norm for trout fishing, except perhaps for the streamer and indicator folks, many of whom have gone to 7-weights. Five weights have largely replaced them, 3weights and 4-weights have become increasingly popular, and some anglers are routinely choosing 2-weights and even lighter lines. Weight-forwards have also largely replaced double-tapers as trout lines of choice. Those are significant changes. Let’s take a look at what we’re doing with lines and tapers and consider the weight-forward versus double-taper issue first.

WF Versus DT

Weight-forward fly lines — now available in multiple incarnations that address specific species or fishing situations — were originally developed to aid in distance casting: You aerialize the head and let it pull an unspooled length of small-diameter running line behind it. But think about this: If the first 30 feet of a double taper and a weight-forward weigh the same and have the same diameters and tapers, and if you cast no more than 30 feet of line past the tip top, there’s little benefit to a weight-forward taper. Thirty feet of line, 9 feet of leader, and the length of your fly rod will generally get you out 40 feet or so, and that covers most stream trout-fishing situations. Double-taper lines also tend to be a bit more economical than weight-forwards, since when one end of a double-taper line wears out or gets trashed, you can simply switch it around, instead of buying a new fly line.

OK, there are a few advantages to a weight-forward line in trout fishing. It takes up less space on your reel, which lets you either use a smaller, lighter reel or hold more backing (for that trout that might just maybe run all of 75 feet). And you might need to make longer casts in a big river or in lakes where reaching spooky fish or retrieving a fly over a longer distance gets it looked at by more fish. Weight-forward lines can provide that distance, though mending line is tougher, unless you go to a long-belly version. (And you’d probably be better off with a dedicated shooting-head outfit, if distance alone is your game.) I suspect the shift from double-tapers to weight-forwards for trout fishing was as much a fashion choice as anything else, based on the psychological advantage weight-forwards provide anglers who like to know they can cast farther, if they need to do so, even when they probably won’t. I doubt that manufacturers objected, since it pretty much ended the two-lines-for-the-price-of-one feature of double-tapers.

Long Rods, Short Rods

Rod-length preferences have also seesawed from long to short and back again. Rods of 9 feet and longer were the norm in the first third of the twentieth century, but from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, the basic American trout rod was 8 feet or shorter (although larger Western waters naturally led some anglers to longer lengths). Short rods were seen as both lighter and more sporting — more challenging — though this preference wasn’t necessarily linked to lightweight lines. Notable anglers such as Lee Wulff promoted very short rods for everything from trout to salmon, but the short bamboo and glass rods that Wulff fished still took 6-weight and 7-weight lines. Wyoming guide and tackle shop operator Jack Dennis praised the new fiberglass Scientific Anglers “System” rods in his 1971 catalog by telling readers that the 7-foot 7-inch 5-weight had the power of an 8-foot rod, although he also mentioned that he still preferred a little 6-1/2-foot Orvis for small streams.

Perceptions of appropriate line weight, rod weight, and rod length changed again when graphite came on the scene in the mid-1970s. Where it was difficult to build an 8-1/2-foot or 9-foot rod in glass or bamboo for anything much lighter than a 5-weight line, doing so was relatively easy with graphite. Manufacturers could now promote the delicate presentation and sportiness of a light-line rod that at the same time offered the superior line handling and tippet protection afforded by greater length. Fenwick’s 9-foot 5-weight HMG was the first of the good long, light-line trout rods, followed closely by Scott’s 9-foot 4-weight. A slew of others followed shortly thereafter.

As sensible as such tackle is seen to be today, it wasn’t an easy task to sell the angling public on it, particularly in the tradition-bound East. Nine-foot rods were still considered salmon and saltwater tackle, and 4-weight lines were mostly thought useful for delicate, small-stream work by experts. By the end of the 1970s, however, although there were pockets of anglers who continued to favor short rods, the pendulum had swung pretty clearly to long and light. I recall an Outdoor Life cover photo from about 1977 of Lefty Kreh, always ahead of the curve, breaking a fly rod across his knees, under the headline “Why Is This Famous Angler Breaking His Short Fly Rods?”

Going Lighter

Where are we today? On the one hand, many fly fishers are still clearly fans of long, light-line trout rods. The 9-foot rod is once again pretty much the standard fly-fishing tool, particularly in the West. We’re also still interested in going “light,” though that term has now begun to mean something very different from what it did in the 1970s. Sage, Scott, G. Loomis, Winston, and rod manufacturers broke new ground when they came up with 81/2-foot and 9-foot rods for 3-weight lines. Orvis shook things up even more in the late 1980s with the introduction of the first 2-weights. And a couple of years ago, Sage’s TCL series of rods for lines even lighter than 2-weights stirred the pot once again.

So what do you get when you go to a 3-weight or lighter? To the right is a table that compares standards from both the old letter and current AFTMA classifications for flylines. Clearly, the first 30 feet of a 1-weight or 2-weight line is considerably lighter than that of a 3-weight or 4-weight weight. And since a fly line’s weight should have a direct relationship to how delicately it lands on the water, a lighter line should be more stealthy. That’s the theory, anyway.

Diameter and Taper

This brings us to diameter and taper, the other significant variables in fly lines. Taper in a modern fly line — the change in its outer diameter along its length — is created by bonding a polyvinyl chloride or urethane coating of variable thickness onto a level-diameter core line. Lines from 2weight to 6-weight are built on cores of about .022 inches, which lets manufacturers create tips down to diameters just under .030 inches. Lines lighter than 2weight are built on cores as small as .018 inches, but material properties and the coating process allow for tips only down to .025 inches or so.

The result is that very light lines tend not to have much diameter change between belly and tip: something like .002 to .003 inches for a 1-weight or 2-weight, as opposed to .010 inches or more for a 5-weight. You’re not casting a level line when you’re using a 2-weight or lighter, but it’s darn close, and you have to wonder just how delicate it’s really going to be. Moreover, making that line work for you not only requires a delicate and very well-balanced rod (and the TCL 1-weight I cast recently was just that), but also a considerable amount of attention to casting technique. These are not beginners’ outfits.

Interestingly enough, the old braided silk fly lines were generally smaller in diameter than contemporary coated lines, sometimes by as much as 25 percent. The nominal belly diameter of an HFH (4weight), for example, was .035 inches, and tips were .025 inches. That’s smaller than any of the 4-weight lines that I fish, and in diameter, at least, it’s about the equivalent of a modern 2-weight, though with more difference between belly and tip. And that standard HDH at .045 to .025 inches was quite a bit thinner than a contemporary 6weight. So if the diameter-equals-delicacy argument holds, a silk line that has to be treated to float and then stripped off the reel to dry out so it doesn’t rot still has something going for it. Many traditionalists, mostly among the bam-boo covens, still fish silk for just that reason.

Anglers who are critical of very light fly rods and lines acknowledge the value of delicate presentation, but point out that there’s generally between 7 to 15 feet of tapered monofilament or fluorocarbon between the line and the fly. That minimizes the value of any weight or diameter difference between, for example, a 4-weight and a 1-weight. Moreover, on many trout streams, you’re rarely casting farther than 35 feet. Use an 8-foot rod with a 10-foot leader to make a 30-foot cast, and you’ve likely got less than 12 feet of line extended past the tip top. And what’s extended is basically just the tapered section, which is the skinniest, lightest, and most delicate part of the line.

Critics also argue that fly lines lighter than 3-weights require dead-calm conditions to cast accurately, even at short distances, so they’re more difficult to use. The light-line folks respond by noting that thinner fly lines offer less resistance in the water when a fish runs and that this helps protect very light tippets. The anti-lightline group counters by arguing that most trout don’t run much and that ultralight fly rods take too long to bring fish to hand and therefore kill trout. And so forth, and so on. . . .

The Role of Personal Preferences

These are all amusing debates, and I suspect we’ll go on splitting hairs over them for as long as there are trout. Ultimately, the choices we make about tackle are about our desire to gain whatever advantage is possible, about taking on new challenges, about increasing the enjoyment we receive from fly fishing, and partly about following the fashion of the day. We choose weight-forward lines because they seem more modern than double-tapers, because we like the idea that we can, if needed, lay out a long line, and because manufacturers have come up with multiple taper options in the weight-forward configuration. (Spring-creek taper? Pocket water taper? Distance taper? Take your pick.) We fish very light rods and lines because we like the sense of being as stealthy as we can, though it may be only an illusion, and because we like to push the envelope, to challenge ourselves. That’s just what the midge-rod folks were seeking in the 1960s and what anglers in the mid1970s were after when they jumped all over 9-foot 4-weights. (It’s also probably what the Spey crowd is after when they fish for trout with 12-foot 5-weight double-handed rods and fly lines whose diameters and weights exceed that of the lines single-handed anglers use for striped bass or tarpon.)

So if a 3-weight or a 4-weight fly rod seems stealthy, fun, and challenging, then a 2-weight, or a 1-weight, or a 0-weight might just be better. If it makes an 8-inch trout feel like it’s a foot long and a 15-incher feel like a steelhead, so much the better. And if there are a few extra bucks in the wallet, who’s to tell us it’s foolish to give one of these rods a try? That our fathers took as many fish and got as much pleasure fishing a 6-weight or an even heavier rod is beside the point. New tackle makes us better anglers. At least it’s pretty to think so.