It was pretty much a perfect afternoon in mid-May. The air was bright and clear, and although the sun was warm there was still a bit of a chill in the shade. The willows were just coming into bud, and the first wildflowers splashed color here and there. My wife and I were fishing a fairly popular stream in the eastern Sierra. A few cars were parked along the road, but it wasn’t what I would call crowded. I was taking a break, sitting on a rock on a ridge, listening to the competing songs of arriving birds and watching my wife as she worked the water below.

She was fishing a downstream drift out of a riffle into the head of a large, long pool. It was a pleasure to watch her meticulous and deliberate approach to each cast as she mended and manipulated the line to get the maximum useful drift. Maybe she was getting hits — I couldn’t tell exactly, but sure wanted to think so. Because she was concentrating on her task, I was the first to see the guy who was approaching from downstream. The pool is large enough to accommodate two, maybe three people working together, but this unknown angler kept moving upstream, making quick casts until he was casting into the end of my wife’s drift.

He was a fairly big guy with a fairly big knife strapped to his hip. She was a woman, seemingly alone on the stream. Probably he is a really great guy who I would want to have as a friend, but that was not the impression he was giving off. I saw my wife shifting down from the riffle to the pool and decided I would walk down the hill and show myself.

The man turned and glared daggers at us, making a big show of sitting down in order to occupy the entire pool for his own use. My wife and I looked at each other, nodded, and moved along to look for another location. The day was no longer quite so perfect.

Sadly, this type of behavior is not especially uncommon. There are iconic destination streams on the east side of the Sierra where exposure to questionable behavior is simply a part of the price of admission. Increasingly, I do not want to pay that price. Land a trout or two, and people begin to creep toward you from up and down the stream. People wade Hot Creek, even crossing in front of signs discouraging the practice. The East Walker is fished on days when the water temperature has put the trout at the edge of their tolerance. Groups of anglers muscle individuals off stretches of the lower Owens.

Certainly, over the decades, fly fishing has evolved from something considered “high-brow,” an activity for the elite, to a more egalitarian and commercialized sport. Perhaps a decline in civility is an inherent part of this change, but it’s also possible that shared assumptions about how to treat others on the water have simply not been passed along to new participants in the sport.

In one of my favorite fly-fishing books, a memoir written in the 1950s by a famous British angler, one gets the sense that everyone who fished then was a member of the peerage, a “smashing” war hero, or a captain of industry or state. The rituals associated with a day on the stream — most likely a private and expensive stream with access limited to those thus privileged — were elaborate and most certainly not to be violated. Even assuming that these ethics were representative of a widespread reality, the world to which they belonged is most certainly a part of the past. I wouldn’t advocate a return to those times, but it is worth remembering that each angler is a part of a matrix that includes not just the natural environment and the fish, but other people.

Later on that May afternoon, my wife and I shared a beverage and talked about what had happened. Actually, the “what” was pretty clear, but we struggled to understand the why. Was this person unaware of his conduct and the etiquette associated with fishing? Was he not paying attention? Did he simply not care and believe he was entitled to the spot of his choice? Did his behavior have nothing to do with fishing and just represented something else about him? Were we overreacting?

The issues in this case, of course, are ones of space, and common sense, and courtesy. The essence of fly fishing for me is the opportunity to try to solve the problems presented by a selected bit of moving water. To do this, I would like enough room to exploit my casting and line-handling abilities, such as they are. We have all experienced an invasion of our space. It may be the anglers who move, yard by yard, in your direction, especially if you were the first to locate a prime spot or if you are enjoying some success. Perhaps it is a “Use it or lose it” mentality: someone who is merely looking at the water and thinking about how to fish it is perceived by other anglers as not actually fishing that spot.

Then there is the guy who wades through your water, maybe thinking he is far enough away, but still creating a disturbance that puts down your fish, or the person who walks into your back cast while moving upstream or downstream behind you. Any of these things is irritating, and we all hope we don’t do them ourselves.

The more difficult question is how to respond to breaches of etiquette. The strategy I employ most is to avoid the issue altogether by fishing in places that others ignore. Mostly this works fine, but I am not willing to deny myself visits to popular waters like Hot Creek, or the Owens, Walker, or Carson Rivers, so I have to deal with it. A day’s fishing should be soothing, rather than a source of frayed nerves. Plus, tensions and anger can sometimes escalate pretty quickly.

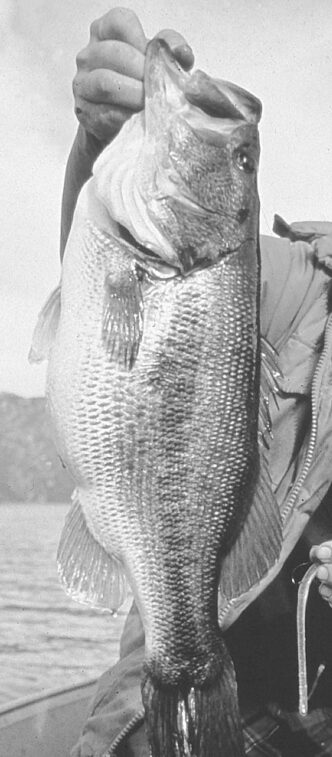

Occasionally, it is apparent that someone probably does not know what is up. If so, I try to respond politely and with respect and point out what seems problematic. This is not a debate, and the point is not to start an argument. Otherwise, the choice is to move along or to stand my ground. It is a question of how I want to use my time. To say that a stream such as Hot Creek, near Mammoth, is heavily fished, would be a massive understatement. There are good reasons for its popularity. The stream is easily accessed, contains a lot of fish, many of them sizeable, and maintains a constant water temperature throughout the year, giving rise to massive insect populations, which almost guarantees that there will be something coming off the water on any given day. It is popular with guides due to a combination of the demand from clients and the availability of fish. I fish the creek several times every year, so I am part of the picture there. The creek attracts anglers of every level of skill and experience, and you can see a huge spectrum of behavior there.

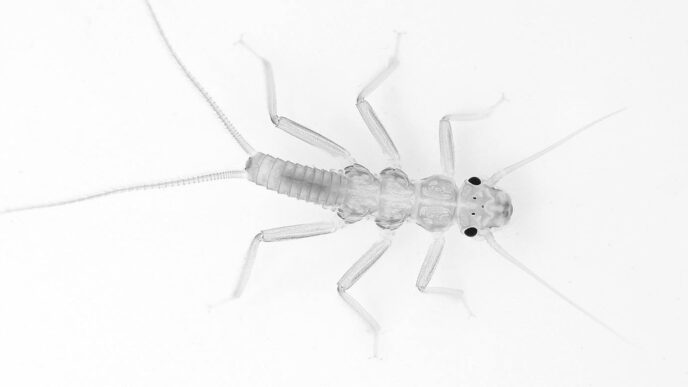

There are signs posted at the creek at parking areas urging that people not wade the creek. The message is repeated on bumper stickers distributed by fly shops in Mammoth. Wading is discouraged because the creek’s insect factory is maintained by the rafts of vegetation that grow up from the stream bottom. Wading tears this away from the streambed, diminishing food production. It is true that some of the dislodged plant material comes from the hatchery upstream, but certainly not all. The fact is, though, that many anglers come equipped with their waders and are determined to use them. Masses of dislodged vegetation floating downstream is just a fact of life. At times, these green masses are accompanied by clouds of silt, which can impair the angling.

Wading any stream presents several issues. If, like me, you spend time fishing out-of-the-way places, you are dependent upon natural reproduction to maintain trout populations. Gravel runs and substrate are vital to this process. These can be harmed by wading. This is particularly true in the spawning seasons, when it is possible to rip apart spawning redds by carelessly walking through them. Even after the fish have left the redds, the eggs and the fry that remain need intact gravel beds to hatch and grow.

Just to be clear, I wade when I fish, even in small streams. Sometimes I wade to cross, and other times to improve a casting location. So I am certainly not saying never wade at all, just be mindful as you do it and keep the stream healthy for when you decide to come back again.

Often, people tell me that they need to wade Hot Creek to land and release fish. This is just not so. Fish can be released if they are carefully played to the bank. It requires some bending, but even at my age, I can kneel down and usually remove the hook without bringing the fish out of the stream. If you do not feel comfortable with your ability to release fish that way, carry a soft fabric net of sufficient size and handle length to let you reach into the water from the bank.

Care for the fish is obviously important, too. Refraining from fishing sometimes can be the only ethical choice. It was really hot this past season in the eastern Sierra — in the 90s in the town of Bridgeport, for example. Stream flows into the East Walker from Bridgeport Reservoir were quite low. One hot, sunny morning I had to travel north for a meeting and took the route that runs along the river. I saw many places where the river channel could be easily crossed by wading. These are conditions in which the trout are vulnerable to oxygen depletion and stress from high water temperatures. At midday, though, there were vehicles parked at every turnout. Even though I was mostly watching the road, I counted more than twenty anglers between the dam and the bridge. I wondered if those people understood how fish can be damaged under these circumstances. During the hot days of summer, various websites and the staff of local fly shops advise keeping off of the river after ten in the morning, yet here was all this activity.

Putting aside the “Do fish feel pain?” questions, they certainly can be harmed by being caught and released. One threat is a potentially fatal build-up of lactic acid during the process of playing and landing. Preventing injury starts with tackle appropriate to the fish likely to be taken. The thrill of a long fight with a large fish on tackle that is deliberately light for the situation comes at the expense of the fish. Barbless hooks cause less injury in both the hooking itself and the removal of the fly. The size of the hook should be appropriate to the potential fish. Fishing for small wild brook trout in the wilderness using hooks as large as size 12 or even 14 runs the risk that a fish can injure itself on the take by being hooked in the gill or eye or by the hook penetrating the brain.

There are a growing number of stream restoration projects underway in the Sierra. This represents an increased awareness of the role that upstream river health plays with regard to California’s overall water supply, and also reflects the fact that there are just no new streams being created out there. It is a trend that is important for those of us who fish, but it comes with some costs. Projects often create restrictions in terms of access, season, technique, or take. People react negatively to what they perceive as an infringement upon their freedom of action, even if the ultimate result could be an enhanced fishing experience.

For example, the Lake Crowley tributary project involved rehabilitation efforts at Mammoth Creek, McGee Creek, Convict Creek, and the upper Owens River. The project treated miles of stream and included the installation of miles of fencing and gates designed to redirect the effects of grazing and human activity. It has been in place since the early 1990s and represents a partnership between lessee ranchers and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

By and large, it has been a success. Anyone who fished those streams before the start date can see significant improvement in stream cover, depth, and stability. There are also a lot more trout, there are larger fish, and there is more successful spawning. It would seem as if common sense and courtesy would motivate anglers to cooperate in an effort that will provide them with more and better fish, but many did not see things that way, breaking down gates and cutting fences so that they can drive right up to the stream banks, as they had in the past, parking in pasturelands, and of course, leaving their trash behind.

Ultimately, though, common sense and common courtesy is the theme that runs through all of our days on the water. People speak of angling etiquette, but how we act when on the stream is not a matter of a bunch of rules. Rather, it involves a commitment to our sport, its many settings, and the future. I know I have done some stupid and neglectful things while fishing. My reaction has been to hope that nobody saw me do them and to hope no one would think I believed my conduct was acceptable. Mostly, anglers — and, at the risk of being smug and elitist, particularly fly fishers — want to do the right thing. Each of us can help make that happen, not by being preachy or prescriptive, but by showing the way. It is important to help people learn and pass along a friendly hint now and then. Sometimes this is going to be met with a negative response, and then it is time to walk away and remember that a single incident does not define an entire group or experience.