A largemouth bass in a local pond or lake may be the smartest fish you’ll ever face.

No doubt, some will scoff at such a statement. Anyone who has fished a woolly bugger in a pond knows small bass can be easy to catch. Of course, the same gear also catches plenty of small trout. Larger fish are more difficult to fool and become even more challenging when the water body gets a lot of fishing pressure. Some of this is because the fish learn to avoid certain flies and presentations, but that’s only part of the story.

Biologists have shown that the feeding behavior of individual fish ranges from bold to timid. The bold risk-takers are generally easier to catch, while the timid ones can test your patience. In waters where angling is very popular, the bolder fish are more likely to end up on the table or to die from poor catch-and-release practices. As a result, the remaining population will have a higher proportion of timid, harder-to-catch fish. It has also been shown that timid fish produce timid offspring. This means the proportion of bold fish will continue to decrease, generation after generation, until a new bold/timid equilibrium is reached. Simply put, the more heavily a body of water is fished, the harder the fishing gets.

So what’s so special about bass? The popularity of largemouth bass fishing means the waters they inhabit are often subject to more fishing pressure than most trout streams. Regardless of whether it’s a one-pound bass in a local pond or a three-pounder in a nearby lake, fooling these fish can stretch your fishing skills to the limit. If you are looking for a new challenge and this sounds like your kind of thing, here are a few tips to get you started.

LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

Watching where conventional anglers fish is an obvious way to find bass. Most of the time, they’ll be casting towards large pieces of structure, such as downed trees, docks, or rock outcrops. Not surprisingly, these spots get pounded, so you may need to be the first angler on the water to have a decent chance. The fish probably don’t see many flies, which can help, but once the water’s been disturbed, they’ll probably be extra spooky.

REMOVE THE WATER

Fortunately, there are often good spots that regular anglers don’t notice. To find them, you need to “see” things you can’t see. Stand by a stream, and the currents give you a good idea of where to cast. The lack of moving water can make ponds and lakes harder to read, but evolution has preloaded a neat solution in your brain. Instead of looking over the water, mentally remove it and “see” the land beneath. This mind’s eye map helped our hunter-gatherer ancestors find food, and it can help you find fish.

Start by looking at the surrounding lands and visualize how the ground slopes as it extends beneath the water. Steep slopes provide deeper water closer to shore, while gentle gradients create shallows. Points or promontories produce a finger of shallower water, with steep side slopes. Pretty soon, you’ll see the underwater scene as easily as if you were looking over dry land.

PATTERNS AND LIGHT

Once you have the map’s contours sorted out, look for pattern changes in lakeside vegetation. Willows or bright green vegetation will often reveal small creeks and ephemeral streams. In winter, these creeks bring earthworms and grubs into the lake, while in summer, their underground flows can feed underwater springs with cool water.

Adjacent wetlands often connect to the main water body through shallow channels. These can provide bass food, such as dragonflies, crayfish, rodents, small fish, and amphibians. Reeds and aquatic plants often create bands of vegetation along the bankside and can hold a lot of food. Bass will often patrol the edge of this vegetation or select specific areas to ambush prey.

The shadows from trees provide a transition between sunlit and shaded water, which bass will often use to ambush prey. As you get more familiar with the water, you’ll start to notice less obvious elements, such as sunken tree limbs, solitary rocks, or old root wads. These can hold big bass. This point was driven home when I spent a day on an electrofishing boat. We stunned a lot of large bass in places that, at first glance, didn’t look at all “bassy.”

Structure fishing is interesting, but it’s not the only game in town. Bass can also be found in open waters with no discernible structure. To fish these areas effectively, you need to work the water methodically. Move a yard or so every few casts to ensure you cover as much water as possible. Fan casting can help, especially if bankside access is limited.

RODS AND LINES

Most modern 6 or 7-weight rods are capable of handling large bass and large flies. As for reels, anything with the capacity for a 7wt line is fine. Don’t worry too much about the drag, a bass fight is more about Mike Tyson power than Usain Bolt speed. When it comes to lines, it’s nice to have a floater and a medium-fast sinker, but if you are limited to just one line, make it the sinker. Floating lines are great for fishing topwater, but, like trout, the majority of fish will be caught on subsurface flies.

FLY SELECTION

Largemouth bass will eat pretty much anything that moves, such as dragonflies, crayfish, bluegills, frogs, salamanders, earthworms, birds, snakes, young bass, and, in some lakes, planted trout. That list should give most fly tyers plenty to work on. While it generally doesn’t hurt to tie realistic patterns, don’t add claws to your crayfish flies. It’s been shown that bass prefer prey that doesn’t bite back.

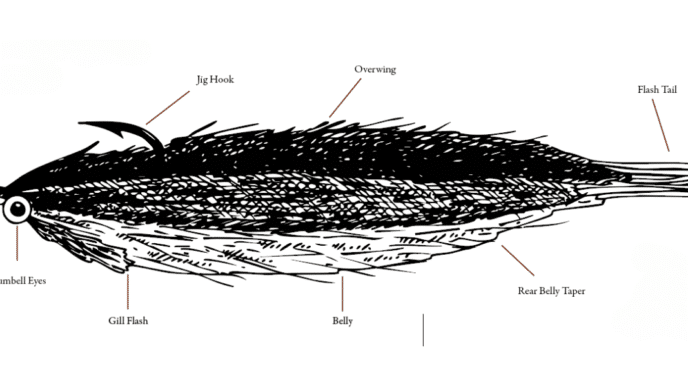

For folks who don’t tie flies, there’s a decent selection of bass and pike flies that do a good job. Make sure your fly box has some two-inch long streamers and critter flies, a few poppers or gurglers, and a handful of four-inch plus streamers.

Your fly needs to move enticingly to seal the deal. For creature flies fished along the bottom, a lot can be accomplished through the retrieve. While dragonfly nymphs and crayfish move rapidly in response to threats, their normal pace is more leisurely. A hand-twist retrieve that moves the fly about two inches per second is a good starting point. If that doesn’t work, slow down or speed up. Every 20-30 seconds, make a quick strip to move the fly a foot or so. This can trigger a bass to strike. Bites can be subtle ticks, a momentary loss of connection, or, more rarely, a solid thump.

The fly will often be moving over twigs, weeds, and rocks, so a weedless pattern, or one tied with a weedless knot, is the way to go. For more info on weedless knots, check out the Winter 2025 issue of California Fly Fisher.

Things get a bit more complicated with baitfish patterns. The natural inclination of many tyers is to tie established streamer patterns. This is a good starting point, but how a fly looks is often secondary to the way it moves. Many streamers that work in rivers aren’t quite as lively in still water. Smart bass will follow these flies but may not attack them. A fly with some side-to-side action, like a Wobble Fly, Tullis Wiggle Bug, or Gamechanger, is often a better choice.

Don’t get stuck in a metronome retrieve; it seldom increases your chances. Vary the retrieve so the fly stops, slows, or darts every few seconds. Bites are generally solid thumps, but it’s best to strike whenever something feels different.

Another important factor is buoyancy. Sometimes bass want a fly that hovers in place or barely rises or falls when you stop your retrieve, which is how real baitfish behave. Bass will often strike when you start to move the fly after a short pause. In a pinch, you can use adhesive-backed foam sheeting to offset the weight of the hook.

When it comes to leaders, you want a setup that allows you to cast relatively accurately with a heavy fly. Six to eight feet of straight 10-pound monofilament is usually fine for topwater and midwater fishing. If you need a heavier butt section, four feet of 30-pound monofilament should do the trick. When working flies along the bottom, it’s hard to beat three or four feet of 10-pound mono.

DEPTH

How deep the fish will be varies throughout the day and season. Topwater action is usually best in the early morning or evening, especially in the summer months. Early mornings are also when bass can be found very close to shore, but they will spook easily. A floating line is the obvious choice for this situation.

If the bass aren’t feeding on top, you’ll generally do better with a sinking line. Don’t immediately assume you need to fish on the bottom, the fish can be anywhere in the water column. This is when you use the countdown method to present a baitfish pattern. Start with a count that allows the fly to get down a couple of feet, and add a foot or so on each cast until your fly touches bottom. When you hook a fish or get a grab, make a few more casts to the same spot, using the same count. You may have located a school.

BITE DETECTION

Detecting soft bites can be a problem when fishing on the bottom. The main reason is slack, which is caused by line sag. Density-compensated lines are less prone to sag and are worth adding to your arsenal. Keep the rod tip in the water, so the line forms an almost straight path between the fly and your hands.

Another solution for line sag is to use an 18-inch-long shooting head attached to clear monofilament shooting line. Mount the fly above the head, and you have a fly-fishing version of the conventional angler’s drop shot rig. The direct connection to the fly helps you detect bites that would be almost impossible to feel with a regular fly line. Another advantage of this setup is that it doesn’t require a backcast, which makes it especially useful for bank fishing where access to the water is through small openings in trees and bushes. A full description of this setup can be found in the October 2020 issue’s Gearhead: Shrunken Heads article.

If this all sounds too simple, perhaps you should concentrate on smart carp. Apparently, it can take decades of fishing to catch the smartest ones.