Shane Chung imagines it’s all been caught on film. Somewhere in footage shot by security cameras peering into parking lots around LAX, he’s sure he’s shown handing over an unmarked packet to a “mule,” a perfect stranger willing to carry a quick shipment of goods aimed to satisfy a sudden demand in Baja. With the immunity of innocence, Chung delights in these deals: out of the chaos that surrounds the busy airport, suddenly there’s a car model or color or some physical aspect of the stranger himself — a recognition that creates a connection between two anglers who, like so many of us, might otherwise pass like ships in the night.

Shane Chung ties flies. He contacted me this summer, hoping I could deliver a fresh batch of an as-yet-unnamed pattern, a fly that had caused a stir among the panga fleet working out of Punta Arenas. I was happy to play along. When it comes to outlaw fantasies, I can do as well as the next guy. What is the sport of fly fishing, if not an invitation or license to walk on the wild side?

The appeal of crossing borders armed with potions and secret talismans — a secret stash devised for the express purpose of an engagement with ritualized sport — is no different today from when my father first hauled me and my mother and sisters down to the beaches of northern Baja to pluck lobsters from the rocks and kelp more than fifty years ago. More than fifty years ago — long enough, anyway, to gain some perspective on such adventure, as well as the notion that you had better show up in Baja with the Right Fly, one delivered by a dark stranger outside the departure terminals for international flights.

A fly pattern that really matters?

In blue waters off the Baja peninsula? What a joke.

Of course, I’ve been wrong before.

Picture, if you will, a time when you were humbled on some blessed trout water. You know the score: fish up and feeding, good fish, not just feeding, but gorging on whatever insect it is that’s hatching — whatever it is that you don’t have matched with what’s tied to your tippet. Or it’s there, indeed, but you fail again and again to present it in such a way to fool even one of these miserable, dim-witted trout, beautiful as angels lighting up the stream.

Now imagine, if you can bear it, that the feeding fish are all as big as diving pelicans. Or springer spaniels. Better yet, if you’re really imaginative, picture yourself beneath the water and these same dog sized fish are falling from the sky, having shot into the air like missiles fired from a submarine. Imagine, anyway, a lot of commotion — yet none of it adds up to the one thing you want right now more than anything you’ve ever wanted in your life, a grab from one of these fish and that sudden, heart-wrenching pull on the end of your line.

Imagine all of that — and maybe, then, you, as I did, can suddenly get interested in a new fly after all.

New flies are born out of necessity. Tyers tinker and tweak, and if it doesn’t really matter, you end up with patterns as twisted and nonsensical as those from the nineteenth-century Atlantic salmon craze — or as simple as West Coast steelhead patterns from back when you could count on dozens of fish spotting your swinging fly on any given run. That was sort of the thinking during the early decades of offshore saltwater fly fishing. You find a school of pelagic fish hammering bait — who needs more than a tuft of feathers tied to a hook?

Only when fish are present, and you don’t catch them, does serious thinking begin.

Nobody I know gets more chances to watch feeding fish in blue water off Baja — and feeding fish that refuse to eat flies — than my old pal Gary Bulla. Both a guide and an outfitter, as well as a pioneer saltwater angler, Bulla is the first fly fisher I knew who began to field a lineup of patterns specific to the bait — or, if you’d like, hatches — found in Baja waters. Bulla gets busy — he’s one of those guys who seem to operate just beyond the edge of chaos — and he turns to Shane Chung to keep himself stocked with flies he offers for sale to his clients. Sometimes he needs more flies than he planned for. Sometimes he needs them in a hurry.

Especially when a new pattern works better than he or anyone else expected.

One thing you can be sure of: few, if any, anglers agree on when and where and how a pattern begins. The way Bulla tells it, he was south of Isla Cerralvo at the end of his spring season, fishing with Ricky Hall and their panga captain, Valente Lucero. Things were pretty much wide open: yellowtail, big pargo mulattos, some of those teenage-size roosterfish that are really as much as any angler should ever ask for. . . .

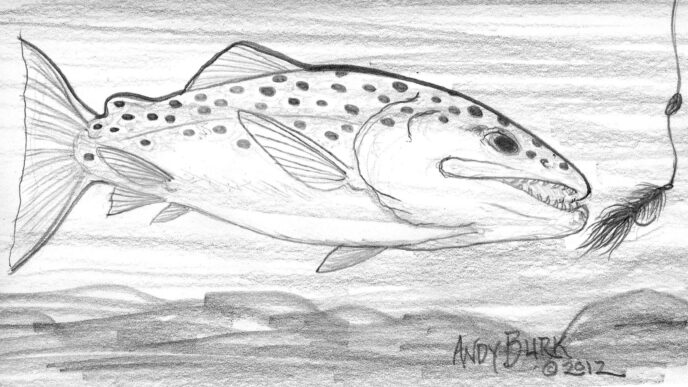

Then some big roosters showed up. When Gary Bulla says “big” roosterfish, he is talking about fish in the 40-to50-pound range. I don’t want to make too big a deal of it, but roosterfish this size have changed the face of West Coast fly fishing. Suddenly, we’re on the map again — the way we were when our steelhead were the envy and aim of fly fishers from all around the world.

But these roosters wouldn’t eat — at least not the standard roosterfish flies, the Papagallos and Tan Sardinas that Bulla and experienced Baja aficionados such as Hall have come to rely on for these elusive giants. Valente suspected the roosters were into something other than the usual flathead herring. He mentioned the color blue, which surprised Bulla, because Valente, over the years, has usually removed any hint of blue or blue flash from flies. Bulla dug through his fly boxes and found a large Tuna Tux with a blue Mylar lateral line. He threw it. A big rooster ate it.

So it begins. The most prominent blue-colored bait in Baja is the flying fish — the volador. Bulla asked Chung to devise his own impression of a flying fish, something five to six inches long with blue saddle hackle and deer hair and flash and a light-colored belly. Call it the Bullador. By the time I saw the fly in the fall, when Chung was shipping them south by way of traveling anglers in order to replenish Bulla’s rapidly diminishing supply, the dressing included Lady Amherst feathers dyed kingfisher blue for the gill plates, as well as badger saddle hackle dyed dark blue for the pectoral “wings.”

Big and blue, the fly seemed at first glance little more to me than yet another variation on a two-tone minnow. I was sure, anyway, I’d be fine without it, that my own evolving Baja lineup would cover what came my way. After all, I’d caught my share of roosterfish.

Even a couple big ones.

But come fall in Baja, roosterfish are no longer the game.

I knew that, too. So when I heard from Chung about picking up flies on my way through LAX, and he told me that the new blue pattern was fooling the yellowfin tuna, I figured the important piece of the equation was that the tuna were there and I was headed that way — and beyond that, I just needed to make sure my knots were sound, my reels oiled, and my back and arms strong enough to go to war with these terrible beasts.

When you first see yellowfin tuna, they are often completely out of the water, having rocketed a hundred feet or more straight up to the surface to claim a single herring tossed into the sea by your obliging pangero. Unable to stop its terrifying momentum, the yellowfin pierces the surface of the sea and tumbles headlong through the air until it finally crashes again through the water and disappears beneath, exactly the kind of disturbance you would expect to see if somebody dropped a 15or 20or 30-pound anvil into the sea. This is the only kind of “rise” from fish I know of that doesn’t just make me drool. I see a yellowfin tuna come out of the water like that and I think Uh-oh. Sometimes, when a big one shows, not just one of 30 pounds, but the kind of yellowfin that more or less makes a joke out of the whole notion of bluewater fly fishing, I think thoughts that I assume are on the order of those shared by the crew of the Pequod when they finally realized that they, not the whale, were the prey.

Of course such thoughts have never stopped any angler or fisher or whaler of any sort from making a cast. Which is probably what that whale of a novel is really about — regardless what you heard in the last course you took in American lit.

The yellowfin tuna, anyway, had arrived, yet another pelagic species that I consider a sucker for virtually anything you toss their way, once you find them and stir their interest to the surface with some well-placed chum. When I arrived in Baja and received the initial fish report, Bulla tried immediately to disabuse me of my cavalier attitude toward flies.

“At least half the tuna hooked last

week were on the new fly,” he said. “I think it’s a real breakthrough.”

“Make sure you get a couple,” added Hall, joining us on a patio with a view of Isla Cerralvo. “I don’t want to be out there spanking fish and have you crying because you don’t have the right fly.”

“Have I ever complained about not having the right fly?” I countered.

“Have you ever been surrounded by yellowfin popping up on the surface and refusing every fly you try?”

Despite appearances to the contrary, I sometimes listen to my experienced elders. Much as I hate buying anyone else’s flies, I purchased a couple of Bulladors — and over the course of the week, I bought a couple more each day, because my daily ration kept disappearing from the end of the 25-pound tippet. Without the Bullador on my line, I caught plenty of other fish — skipjack tuna, big dorados, little roosters. But yellowfin tuna? Sadly, all I can report is that there’s a new fly they seem ready to eat. Your problem, then, is stopping them while, like a contraband-running mule, they set off to deliver the goods somewhere far, far away.

Bullador

Hook: Owner Aki 3/0

Thread: White 3/0 Uni-Thread

Belly: “Polar Bear” color Super Hair

Body: “Smoke” color Super Hair

Back: Blue Super Hair

Wing: Badger saddle hackle, dyed blue

Gill Plate: Amherst pheasant, dyed kingfisher blue

Eyes: 3/16-inch holographic eyes

Head: Clear Cure Goo (or epoxy)