Of the countless iterations of fly fishing, none seems older and less refined than the swing of a streamer at the end of a taut line. And despite all of the fanfare and high-minded chants, the swinging lure defines the essence of steelheading. We’ve all seen enough good work done with a Super Duper or Blue Fox Spinner to question deeply what it is we’re trying to prove with even our simplest trout flies, and as soon as we fashion our first Mickey Finn or Silver Darter, we’re pretty sure the destination traces a route through territory that claims allegiance to its own brand of democracy. A swimming bait, the traditional streamer recalls a time when fish and forage were both infinitely more abundant and, by way of most modern anglers’ logic, dumb as dodos. You could catch a limit back then on doorknobs, we believe. No wonder a Hornberg worked. There’s also the suspicion that the Victorian era, during which the early ethics of the sport evolved, embraced a template of low hems and high necklines, purple prose, and a fanciful denial of subsurface life by a class of anglers who favored the celestial order of the sonnet over the grubby, dog-eat-dog realism of a serialized Dickens novel.

Many of us, anyway, come to streamers with a good deal of skepticism. Or no confidence at all. I’m especially aware of how infrequently a streamer will enliven a challenging day of trout fishing way out here in the Far West. Kelly Galloup notwithstanding, very often knotting a streamer to your tippet feels like a desperate move, one step shy of pulling off your waders and heading for the nearest bar.

It’s different elsewhere. We all hear from friends or relatives who swing or strip streamers through shadows and hidden lies, usually in places without the pitch and vigor of the typical Far West stream. Brown trout are often involved, a part of the equation that further distances the sport from many of our home waters, even though brown trout, like Iowa farm girls, are found in every corner of the world. And I suspect most of us know at least one particular streamer aficionado, often a big fish angler, someone capable of keeping a long, lascivious fly in the water on the off chance of sticking a genuine pig while the rest of us go about meeting our hatches as if gentlemen hoping to network our way into the good graces of firm and fortune alike.

Which is sort of the point: unlike so much else that glitters and glows in the sport, there’s something sly, even sinister, about streamer fishing. We read little about streamer fishing, because really, nobody cares to digest a piece that begins, “I knock them dead with my five-inch rabbit leech and seven-six Pucker Pole.” The whole impetus of streamers and streamer fishing precludes the learned nitpicking and postulates so popular among writers and experts who view fish, especially trout, as proof of their angling prowess.

Or maybe it’s the kind of fish we hope to catch that degrades the status of streamers. Try as we might to claim the high ground, most trout fishers can’t excuse any fish that feeds on trout — and should the predator in question turn out itself to be a trout, indignant anglers can consider the culprit a blight, one that deserves reprimand, if not outright eradication, by any means at hand.

An overstatement? Perhaps. Yet we need only recall the sad fate of, say, the bull trout in California and much of the Pacific Northwest to understand that when we talk about trout and trout fishing, we immediately join a much larger discussion, one that offers its own damning evidence for why so many of our favorite watersheds are in the mess they’re in today.

I mention bull trout with some reluctance. Isn’t fishing for them a little far-fetched? Yet if you wander from California and poke around in waters to the north, you might find yourself in bull trout country, a designation that means you may encounter and can even target these native fish — remembering, of course, that you’re required to do everything in your power to return them safely to river or stream.

And bull trout, don’t you know, were put on earth to eat swinging streamers.

They make brown trout look like ducks. Someone will argue that northern pike are way gnarlier, but my point here is to talk about traditional fly fishing for trout. I’m not going to include mako sharks and bluefin tuna in the discussion, either. I may have to fend off critics who contend that bull trout are actually a char, not a true trout, but unless someone dares to convince members of the Theodore Gordon Flyfishers in New York that Eastern Seaboard brookies don’t qualify as native trout, I think I’m safe including bull trout on our own list of natives.

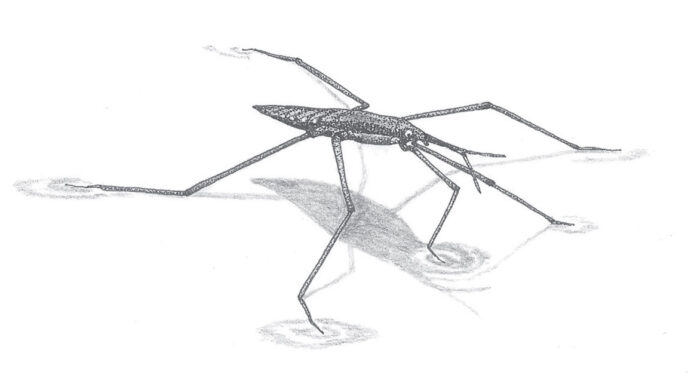

Bull trout, for those who don’t know, belong to the list of elite predators that can and will eat anything that shares the habitat in which they live. Think cougars, peregrine falcons, wolves. When I first heard about bull trout and realized that they feed on the very fish I was trying to catch, I immediately had to recalibrate my image of a healthy trout stream, especially one that justified any sorts of claims that labeled it wild. I also decided I should make it a point to meet some of these badasses on their native turf.

Of course, I can’t tell you where that might be. This is a fly-tying column, remember. I’m also quite aware that there are no secrets anymore, that these days, everyone is capable of tracking down fish anywhere in the West.

But I’m not the guy who’s going to make that search any easier than it already is. What I can tell you about is my favorite bull trout fly, the Vanilla Bugger, the first streamer I also fish when prospecting for any of the other trout typically found in Western streams. Tied with the appropriate golden badger or cream-colored saddle hackle, feathers with those dark, webby fibers that grow longer and longer toward the base of the quill, the Vanilla Bugger offers an impression of fry and fingerlings that seems as perfect in its lack of specificity as a Hare’s Ear’s suggestion of virtually any nymph. I fish a range of sizes, from 2s down to 12s, although the one time I really got into bull trout, not just the odd fish here and there, I would have liked to try a six-inch or even eight-inch Vanilla Bugger, something on the order of what you might throw at a roosterfish in Baja.

Not that it seemed to matter. I knew I was in a bull trout drainage, but it seemed just as interesting to stir up some action on spunky rainbows with a little red Humpy. I didn’t raise anything in the first lie, which seemed odd, considering the stream’s usual generosity with small trout. I finally fooled a fish alongside a half-submerged tree that had taken a section of bank with it when it collapsed in high water, and as soon as the hooked trout squirted into the middle of the stream, a massive gray shape flared from the shadows of rocks and just a quickly disappeared.

Hm.

Minutes later, the same thing happened while I played another small trout. This time, I got a better look at what, apparently, was after my hooked fish. I backed out of the stream and switched flies. At the top end of the fallen tree, I made the same cast I would make if I were steelheading. The Vanilla Bugger tightened the line and began to swing over the shadowy midstream rocks. When the bull trout rose, it never had a chance: I pulled the fly right out of its mouth.

After I settled down and began letting fish eat the Vanilla Bugger, I discovered why I didn’t raise anything where I started with the red Humpy. Bull trout and little rainbows don’t mix. Show a bull trout a Vanilla Bugger, and you’ll know why.

Tying the Vanilla Bugger

The Vanilla Bugger is a signature pattern created by Mark Boname of the North Platte River Fly Shop, in Casper, Wyoming. I heard about the pattern from my old pal Jeff Cottrell while he was giving me some inside dope on Wyoming, specifically, the Gray Reef section of the North Platte. Jeff didn’t have an actual pattern; I began tying Vanilla Buggers on my own, somewhat differently, it turns out, than Boname ties his. Now, years later, you can watch Mark Boname tie a Vanilla Bugger at flytying/vanilla_bugger.aspx. The recipe and directions below are how I tie mine.

Materials

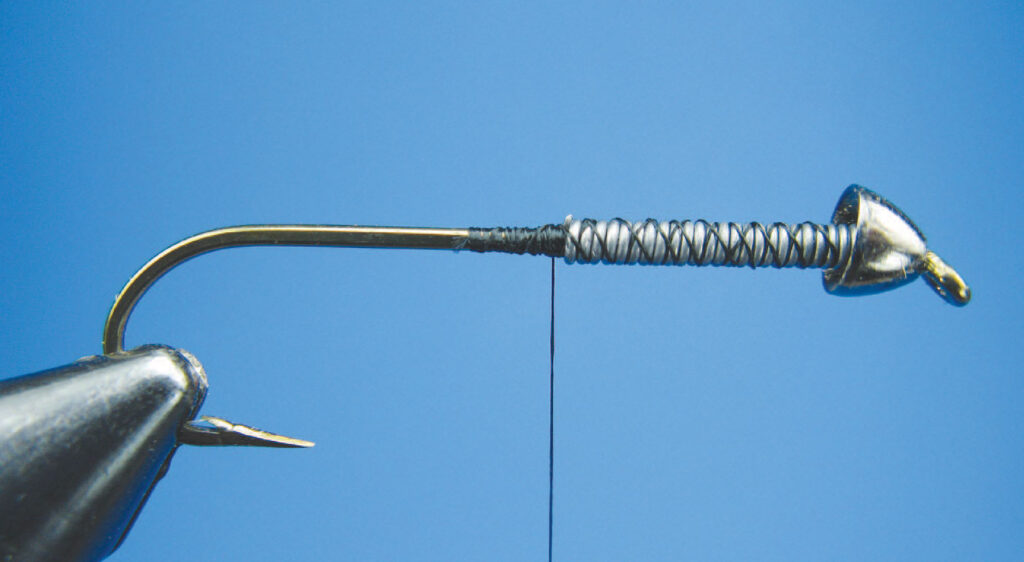

Hook: Mustad 79580, size 2 to 12, weighted (optional) with 20 to 25 turns of .010inch or .020-inch lead wire

Head: Medium conehead, black or nickel

Thread: Black 6/0

Tail: Tan marabou blood plumes, with pearl Krystal Flash

Rib: Small copper wire

Body: Strands of cream and tan yarn, twisted with cream Antron yarn

Hackle: Golden badger or cream saddle hackle

Tying Instructions

Step 1: Since this could be your bull trout fly, pinch down the barb. Slide the conehead around the bend of the hook and up to the eye. Wrap lead around the front half of the hook and jam the coils tight against the conehead. Start your thread, build a dam at the back of the lead wraps, and spiral the thread back and forth over the lead to keep it from spinning.

Step 2: Clip the straight, aligned blood plumes from the center front part of a marabou feather, including the center stem. This is quicker and easier than stripping off the bottom barbs of the feather. Tie in the tail directly above the barb of the hook. You want the tail to be about the same length as the hook shank. Cut the forward excess tail material so that it creates a fair taper from the root of the tail up to the lead wraps.

Step 3: Alongside the root of the tail, tie in a pair of Krystal Flash fibers. Fold the fibers and secure along the far side of tail root, as well. Trim the two pairs of fibers about even with the tips of the tail.

Step 4: Tie in a short length of copper wire at the root of the tail. This will be used later to rib the fly and secure the palmered hackle.

Step 5: For the body of the fly, Mark Boname uses Furry Foam. I’ve never tried it. Instead, I unravel single strands from both cream-colored and tan-colored yarns, and I add these to a length of cream-colored Antron yarn. Secure all three of these pieces at the root of the tail, then twist them to form a single variegated cord. Wrap the cord forward to form the body. Tie off directly behind the cone head and clip the excess.

Step 6: For your hackle, you want a feather with a dark center. Strip the base of the stem, leaving some of the dark, webby material that you would normally discard. Tie in the feather with the stripped base of the stem directly behind the conehead. Hold the tip of the feather with your hackle pliers. Make two wraps tight to the back of the cone head, then continue wrapping toward the tail, making five or six wraps with a clear space between each turn.

Step 7: Catch the tip of the palmered hackle with a turn of the copper wire in the opposite direction. Continue to wind the copper wire forward, working it between the hackle fibers so that it crosses the hackle stem without smashing the fibers. Your bodkin or dubbing needle works well to aid in this.

Step 8: Bring the copper wire up to the conehead. Tie it off with wraps of thread. Cut the copper wire. Trim the tip of the hackle, once the rib has been secured, then whip finish directly behind the conehead.