Steelhead season arrives slowly at The Roost. Nobody really needs any more steelhead flies — our boxes show that most of us tie half a dozen flies for every one we lose — and usually everybody’s been out a few times, occasionally with fish to report, before anyone gets serious about a pattern he needs to tie.

But there might be more to it than that.

Favorite steelhead flies are based on — what? It’s widely observed that the fly an angler uses to catch his first steelhead will return to his tippet again and again throughout his steelheading career. Just as troubling is the “brilliant steelheader” mentioned in a Tom McGuane essay — an angler who fishes only “with flies he finds or is given.”

Try as we might, nobody gets far with claims for a must-have or can’t-miss steelhead fly. Experience has proven that there is no such thing. At best, we settle for the belief that a fly that has worked in the past will eventually work again. Far less magnanimous is one of steelheading’s sourest truisms: you catch fish on the flies you fish with.

Bruce Milhiser, the trout fisherman, seems only to dabble in steelheading. In season, he adopts an off-the-cuff manner that shares none of the drama and highminded cant favored by so many of us who set off in pursuit of anadromous fish. Bruce, I should add, catches more steelhead in less time on the water than any other angler I know.

I’m pretty sure Bruce’s success has little to do with his favorite fly, a small nymph he ties in a variety of colors from a lifetime stash of seal dubbing he bought off a guy who recycled the lining from a bunch of surplus overcoats discarded by the Russian Army. Bruce, a quiet lefthander with the fishing instincts of an osprey, catches steelhead because he’s learned their lies and the casts that present his flies just so, an aggregate of experience and skills that has more to do with his catch rate than any favorite fly.

And “favorite” may even be misleading; his most effective fly is probably a better way to describe the simple size 6 nymph that I see Bruce use most often in red, although he claims he does just as well with versions in purple, brown, and a rusty orange. Still, as a cane rod collector and enthusiast, Bruce tends more and more to fish traditional steelhead flies on the swing, if only because the method seems so well suited to the rods he loves to cast.

“I use the nymph as a last resort,” says Bruce. “And — well, you can guess what usually happens then.”

Without the talents or streamcraft of a Bruce Milhiser, many of us still fall prey to the belief that we just need the Right Fly. How else deal with the heavy toll on our spirits? The sport measures our faith. Not a small number of steelheaders become cynics or fatalists, resigned to the hopeless dread, between strikes, of yet another ten thousand empty casts. Just as many, I suspect, simply quit, convinced by loved ones — or the shadow of mortality — that there are better ways to spend one’s time.

Still, a great many steelheaders embrace the sport because of the very aspects that make it so difficult. Like romantics

who seem to crave the trials of love, serious steelheaders reveal a willingness to experience the profound doubts and uncertainty of most moments spent on the water. Who really knows where the fish are — or if they are — or what makes them grab the fly? At the same time, survivors in the sport — those who return to it each year, no matter how many steelhead they’ve caught, no matter how many times they’ve been reduced to despair — approach the tying vise with their own hard-bitten strategies, most of which say more about the angler than they do about the next fish he hopes to find.

My old pal Fred Trujillo returns again and again to The Roost to tie an oversized, but by no means exotic EggSucking Leech. A professional, Fred ties all of the usual steelhead standards to sell to guides and online customers and audiences attending a circuit of fly-fishing shows he takes part in each year. But Fred never, ever fishes those patterns. His ESL is noteworthy for little more than a pair of dumbbell eyes so large they give the head of the fly the appearance of the front end of your grandfather’s Studebaker. He uses marabou blood plumes for the tail and red copper wire to rib the fly and keep the palmered black hackle in place, and those big eyes give him room to create a head to rival anybody’s single egg pattern, a series of figure eights employing enough chenille to repair both cuffs of a raglan sweater.

Fred catches a lot of steelhead, too. An ex-wrestler, he doesn’t feel there’s the least bit of mystery to getting the job done. “Get it down there and hit ’em right in the nose,” he says. “That’s the way to make steelhead pay attention to your fly.”

Which leaves me — the only other tyer at The Roost this week with the kind of long-term steelheading career that warrants genuine street cred. The youngsters, I’m sorry, just don’t count. At their age, anything seems possible. But without a certain number of steelhead seasons under your belt, both good years and bad, it’s impossible to know for sure if you’re indulging a fantasy or if you’re in the sport for the long haul.

Sadly, I’m convinced I’ve learned little more about steelheading than that I need to keep my fly in the water. I never do that, not for long, when I fish with nymphs, egg patterns, and sucking leeches. Not that I don’t fish such flies now and then. But whenever I do, I think I should immediately hook a fish — and when that doesn’t happen, which is usually the case, I generally say the hell with it and retreat to higher ground. Like the fish I hope to catch, the steelhead flies I keep in the water hour after hour, day after day, are flies I find beautiful, however loose my criteria for beauty may be. No doubt a fly’s success in the past contributes to its appeal. And enough seasons spent chasing steelhead, occasionally even catching a few, gives us all some idea of what works and what doesn’t. Some idea — because we’re still on squishy turf. A fly I consider beautiful looks like it ought to catch fish.

Because I don’t tie to sell, or for clients, or for an audience other than fish, I tie fairly simple patterns, focusing on fundamentals and the best hooks and materials I can find. Different patterns tend to share a common look. Most of my flies are derivatives of proven patterns, tweaked just so to match the kind of water I like to fish, the equipment I like to use, the casts I like to make — and a private aesthetic that boils down to flies I hold up and think, That’s a good-looking fly.

Which brings us, finally, to the Park’s Special. A fancier pattern than I’m used to tying, it’s still relatively simple, once you assemble the long list of quasi-exotic materials. Peacock breast feathers. Silver pheasant. Golden pheasant tippets dyed red. Is any one of these essential? You know my answer. Still, the fly melds so many elements from different classic steelhead patterns that it seems worthwhile to follow the recipe, if only to find out if Parker Stenersen, the creator of the fly, has hit on a magic combination.

Chances are, as I’ve said, no magic combination exists. That’s sort of the whole point. Still, we are all quite sure that some steelhead flies work better than others, and if you carry that notion far enough, there remains the possibility that a true killer fly lurks somewhere just beyond the horizon.

And the Park’s Special does work. At least for me.

This morning, for example, on a favorite run tucked up a twisted canyon where I have more than my share of steelhead memories — encounters with native fish that seem lit with the spark of some impractical genius that makes them willing to jump a fly. Not all steelhead are created equal. First light today, however, revealed the river dark, discolored, soiled by recent rains. I might have fallen into a funk were it not for a Park’s Special, the perfect contrasting hue. Knotted in place, it worked so well that I had no trouble keeping the fly right where it belonged, swinging through the heart of the run, rekindling my faith as I raised the rod tip and pivoted and cast again.

Materials for the Park’s Special

HOOK: MFC (Montana Fly Co.) 7099, size 4, purple

THREAD: Black

TAG: Mirage Tinsel, large

BUTT: Fluorescent yellow Lagartun Mini Braid

TAIL: Golden pheasant tippets, dyed red RIB: Silver oval tinsel, small

BODY: UV purple Ice Dubbing,

COLLAR: Silver pheasant body feathers, dyed purple

WING: Peacock breast feather, blue body plumage

Tying Instructions

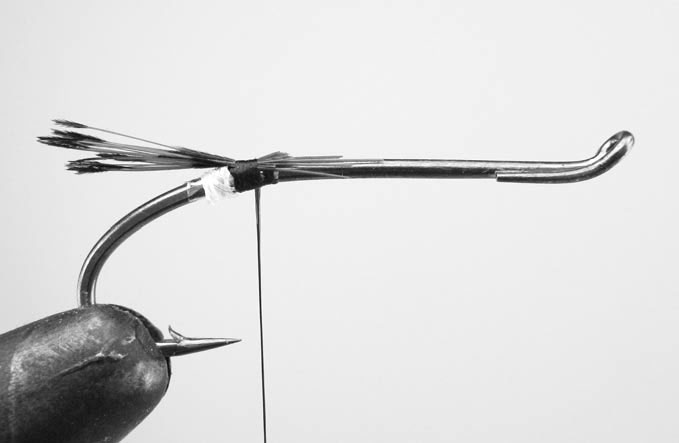

Step 1: Secure the hook in the vise, start your thread, and create a tag the width of one or two wraps of the large Mirage Tinsel.

Step 2: Secure a short length of Mini Braid. Create a butt no wider than a couple of wraps. Clip a dozen or so red golden pheasant tippets and tie in a tail.

Step 3: Secure a length of oval silver tinsel for the rib. With the purple Ice Dubbing, form a dubbing loop or dubbing noodle and create a body that ends about where the hook is doubled to form the eye. For the ribbing, wind the oval tinsel forward with four to six evenly spaced wraps.

Step 4: Prepare the collar feather. With the convex, shiny side of the feather facing you and the tip pointing up, strip the fibers from the left side of the stem. Leave enough of fibers at the tip so that you can tie this portion of the stem to the hook shank. Secure the feather by the tip perpendicular to the hook so that the remaining fibers point toward the butt of the fly. Holding the feather by the butt of the stem, wind it forward, twisting it slightly so that the feather fibers form a graceful curve around the body of the fly. When there are no fibers left, tie off the butt of the stem and clip the excess.

Step 5: For the wing, clip a bunch of fibers from a peacock breast feather. Tie the feathers in a tight bunch over the top of the collar. Clip the butts, whip finish, and saturate the wraps with head cement.