I was surprised to learn that Steven Bird, a recent visitor to The Roost, spent his seminal years as a soft-hackle convert just up the road from me in the

L.A. basin. I usually don’t ask anyone’s age, if only to avoid revealing mine, but it seems likely I might have passed Bird’s way had I ever taken Highway 39 toward the mountains, instead of heading compulsively to the beach. Then again, who’s to say Bird didn’t swing through In-NOut Burger the night I lost my leather jacket — the same night Rodney McNeil disgraced our defense with nearly 300 yards rushing, a game against Baldwin Park that haunted me for the next 25 years.

Still, before our paths might have crossed, Bird had already found home waters far removed from my own, plus the definitive text to embrace them with the fever of young flyrodders anywhere. While I was studying, as so many others did, the photos in Surfer magazine, searching for clues how to imitate Corky Carroll or David Nuuhiwa, Bird — by his teens a regular on the forks of the creeklike San Gabriel River — was reading and rereading The Art of Tying the Wet Fly & Fishing the Flymph, the 1971 Crown edition with Pete Hidy’s new chapters knotted neatly to his original collaboration with the Brodhead’s wingless wet-fly master, James Leisenring.

That book, especially the pictures of flies and the theories that supported their creation, fired young Steven Bird’s imagination. Everything made sense. Everything seemed right. We all know what this is like — or at least, we did, when a book or magazine could transform us with a nugget of inspired insight that helped us penetrate a level of sport previously beyond our reach. At the risk, again, of sounding like an old fart, I’ll contend that nothing in digital media, linked to an infinite number of information bits, is quite like carrying around a single photo and well-scripted caption of a truly gnarly moment — an explosive fish or exquisite wave — one we return to again and again, unmolested by a battery of replies, comments, or impulse opinions clamoring for our immediate view.

The Art of Tying the Wet Fly & Fishing the Flymph grabbed Steven Bird’s attention. It has never let go. Launched into the school of impressionistic, soft-hackled flies, Bird has spent the decades guided by the same principles of fly construction offered up in his copy of that slender book, which grew smaller still as it shed its covers and pages through one reading after another. Movement, obfuscation, the subtle color blending produced by a weave of natural materials — this triad of soft hackle notes has steered Bird toward a harmony of design found most often in the frank, unassuming patterns that seem descendants of an older, less complicated style of fly fishing. Armed as a teenager with his very first attempts at tying “inthe-round” nymphs and wingless wets, Bird discovered the perfect pitch for his forays up and down the hardscrabble banks of the forks of the diminutive San Gabriel, an assault on little trout, bright and feisty as June warblers. He still feels the need to apologize for them.

We’ve both come a long way.

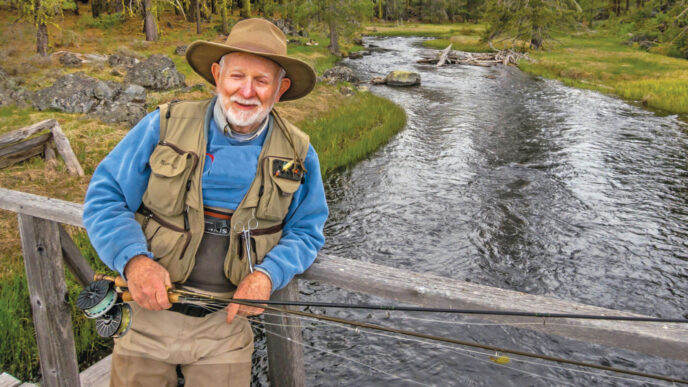

Bird again lives up the road from me — but it’s a much longer road to much bigger water, the American Reach of the Columbia just below the Canadian border, no doubt the biggest trout stream in the West. Bird guides, writes, blogs — a subversive existence common to the sport. Most years, he also overwinters in Morro Bay, where he keeps a home-built Tracy O’Brien stitch-and-glue Oregon dory stretched to 18 feet with a wheelhouse, live-bait well, and external motor mount, a boat he uses for casting flies into the Central Coast salt and all points south. I share all of this not because any of us needs to hear about another somebody who’s gone ape shit over fly fishing. Instead, I wish to clarify that despite Bird’s northward migration, he remains an all but iconic California native son (he actually got started fishing in Massachusetts), an angler with roots that run deeper than most through the fertile turf of California fly fishing.

So we head to the vise.

Pressed to divulge a favorite pattern, a soft hackle that might prove effective on something other than trout as big as steelhead fetched from waters broad and deep as a Swedish fjord, Bird holds up a hand. The trout in the American Reach, he says, feed on the same things as trout everywhere. They can be just as finicky, too, sipping Blue-Winged Olives or little black caddisflies from back-eddy foam lines as delicately as spring creek browns.

“But you’re right about them being as big as steelhead,” he adds.

“Then what do you say we take a look at your Blue-Winged Olives?” I suggest. It’s a hatch with which we’re all familiar — something that doesn’t necessarily make it any easier to match. Little flies, squeaky drifts, snooty fish often feeding selectively on a specific stage of the insect’s life — all of this makes a Blue-Winged Olive hatch an opportunity that most of us have witnessed, only to see our best efforts fail, more than once in our careers.

Many more than once, for some of us who have been around awhile.

“First mayflies of the year,” says Bird. “Last to go,” I add.

Bird ends up tying the half dozen BWO soft hackles he uses most often. Hare’s Ear. Pheasant Tail. Leisenring Black Gnat Variant. Nemes Variant. And on. None of them is particularly unusual; all of them look right, that quiet blurring of color and line that make soft hackles so suggestive of real life. I’m encouraged, as well, that he feels the need to carry the extensive lineup. Apparently I am not the only one who’s found himself pawing through his box in the heat of desperate uncertainty.

Still, is it the fly, or the fly fisher, I ask, baiting Bird with the oldest question at The Roost.

Pattern?

Or presentation?

Bird pauses, gathering his thoughts. He has a habit of waiting before he speaks, the writer’s tendency to want to get the words right. He’s also one of those lean, gray-fringed guys who’s either entering or leaving middle age, it’s difficult to tell which, so that he’s already got the listener slightly off balance. There is, he says finally, no be-all, end-all BWO imitation. Size and silhouette are the places to begin. But the key is simulation.

Simulation. I like that. I like it a lot. It gets right to the heart of the soft-hackle school of fly fishing. All six of Bird’s BWOs — a combination of traditional ties and Bird’s own variants and patterns — offer an impression that, animated in the hands of a skilled angler, will simulate the little critter on which trout feed. These are the same flies, essentially, that the good doctor, Bruce Milhiser, uses so effectively on those big, discerning trout that humble or humiliate so many of the rest of us. Bird’s BWOs aren’t patterns so much as they are a commitment to a style of fly fishing that says the fly’s important, but I’ve got to fish like a wizard if I’m going to make these things pay off.

Still, you have to wonder: Why don’t we see more soft hackles? Why don’t we find soft hackles championed in the sporting press? Why don’t guides favor soft hackles on their clients’ lines? I have a range of unfounded opinions for just about everything that goes on in fly fishing, but in this case, I might actually be right. Soft hackles are imprecise, unglamorous, a fuzzy splash of fur and feather completely lacking in qualities that inspire fly buyers to reach for their wallets. That’s it? you think. How am I supposed to believe in that?

Believe, says Bird.

Still, there’s a lot more to the answer. Bird’s BWOs, like most soft hackles, don’t look like much — unless you picture them alive in the water. Size, shape, color — all of that, yes, plus the magic of movement imparted through those tender hackles by the myriad manipulations of rod and line and leader, partnered with the current, to simulate the emerging Blue-Winged Olive. It’s a complex equation, one founded on a host of variables that fluctuate in direct proportion to an angler’s knowledge, insight, and expertise.

The good news is, the trout will tell you when you get it right.

Materials

HOOK: Daiichi 1150, size 14 to 20 THREAD: Camel or olive, 8/0

TAILING: Bronze wood duck, gadwall, or mallard flank

RIB: 6X Maxima Ultragreen, or fine wire ABDOMEN: Mix 1/3 dark olive, 1/3 medium brown, and 1/3 blue-gray rabbit without guard hairs

THORAX: Natural dark brown hare’s ear with guard hairs and pinch of abdomen dubbing.

WING CASE: Pinch of black rabbit fur HACKLE: Faintly speckled ginger or tan hen or partridge

HEAD: Thorax dubbing in front of hackle

Tying Instructions

Step 1: Secure the hook in the vise and start the thread. Soft-hackle advocates put a lot of stock in different hooks for different applications; the Daiichi 1150, or one like it, is worth tracking down. It’s stout, and the wide gap grabs plenty of flesh, a concern when fighting big, hard running rainbows in big, hard-running water. (And for the record, no hook company cuts me any deals.)

Step 2: Unlike some other tyers, I follow this traditional sequence for all of my soft hackles, rather than securing the hackle feather just before winding it in place. Select a hackle feather with individual fibers about twice as long as the hook gap. Strip the fuzz from the base of the feather and then flare the fibers from the stem. Before securing the stem to the hook shank, flatten it by running it between the nails of your thumb and forefinger. This helps prevent the stem f rom breaking when you wind the hackle. With the tip of the feather pointing forward, tie the hackle stem to the top of the hook just behind the eye, the concave side of the feather toward you. For a sparser fly, strip the fibers from one side of the hackle stem before securing the feather to the hook.

Step 3: Wind the thread toward the bend of the hook. Tie the tail deep in the bend, using the curve of the hook to give your fly the silhouette of a flexed, swimming Blue-Winged Olive nymph.

Step 4: Secure a short length of Maxima Ultragreen (or wire) directly in front of the root of the tail. Then wax the thread and create a dubbing noodle, using just enough premixed material to cover the thread. Bird, like other traditional soft hackle tyers, loves to mix dubbing colors. Build the abdomen, aiming to make it as slender as possible. Rib the abdomen with three or four evenly spaced wraps of the Maxima monofilament.

Step 5: Wax the thread again. Create a plump, spiky thorax out of dark dubbing material from an ear of a hare’s mask, with a trace of the abdomen dubbing material mixed in.

Step 6: For the wing case, tie in a pinch of black rabbit fur from either a Zonker strip or from the very tip of an ear of a hare’s mask.

Step 7: Hold the tip of the hackle feather and take two turns back to the thread and wing case. Then wind the thread through the hackle, locking the stem of the feather in place.

Step 8: Add a tiny pinch of the thorax dubbing to the thread and make a couple of turns in front of the hackle. Whip finish.