Ralph Wood has been a personal friend for many years. We’ve guided together on the North Yuba, tied flies together at many of the major shows and events, told stories, traded flypattern “secrets,” and done all sorts of trout-bum stuff. I’ve never had the opportunity to fish with Ralph outside of guiding, but we’ve exchanged greetings from across the river a few of times on the beautiful lower Yuba.

Years ago, when Ralph and I were travelling Highway 49 from Nevada City to Downieville to do a North Yuba guide gig on a windy, rainy day, he told me a few stories about his life before guiding. One little vignette, in particular, reflects Ralph’s deep commitment and attachment to our sport. Years ago, Ralph was a stockbroker in San Francisco, accustomed to big-city living, wearing suits and ties, and sitting in long, boring meetings. One fine day, in the middle of a particularly annoying meeting, Ralph got up from his chair, harrumphed, gathered his papers, stuffed them into his briefcase, removed his tie, said goodbye, left the meeting and the city, and never looked back. The next day found him onstream, trout bum versus trout, and the rest is history.

That rainy morning on the North Yuba yielded some eager trout to our drenchedto-the-skin, but undaunted sports. Sitting under the picnic shelter at Convict Flat, drinking coffee and eating lunch, looking out over the fog-filled canyon stretching upstream and down, few words were spoken as the strikingly beautiful scene soaked our psyches and primed us for the rest of the day. At least for me, it just doesn’t get any better — shivers and all.

Later, as Ralph and I wound westward on Highway 49 toward Nevada City, he pulled the car into a turnout. “C’mon, I want to show you something,” he muttered as his door slammed shut. We crossed the road, hopped the guardrail, and struggled though some dripping brush to a bluff overlooking a large, deep pool 50 feet below. My eyes popped out when they spied several very large trout finning lazily in the current, moving occasionally to take a passing piece of food, then returning to position. “And some people say there’s no large fish in the North Yuba, eh?” he said with a knowing grin. I studied the water. “Looks to me like it’d be really hard to get a good drift with all of those conflicting currents,” I answered, with the cunning look of a fly angler faced with a challenge. “Too bad it’s getting dark.” Ralph shot me look. “This is a secret place,” he warned. I’ve honored that secret to this day, although I do admit to slinking back a few times when no one else was around.

As I was talking with Ralph while watching him tie flies at an otherwise long-forgotten show, a sleek little streamer lying on the base plate of his vise caught my eye. “What’s that?” I asked. “Aw, it’s just something I’m working on,” he replied. “Here, take a couple and try them on the lower Yuba.” So I did, with my switch rod equipped with an intermediate tip. After losing both of my samples — one to a fish and the other to a rock or whatever — I returned home and cranked out a few of my own. They are a fine addition to the small box of streamers I carry when hiking canyon trails for trout.

A little more about Ralph before we hear directly from him: Ralph grew up in New Hampshire. His love for California’s myriad freestone streams and others across the West is directly traceable to his streamcraft-apprentice years on the Granite State’s predominantly small freestone streams and brooks. Today he is a well-known fly-fishing guide and speaker, as well as a demonstration and custom fly tyer who often appears at tying events sponsored by the Northern California Council of the Federation of Fly Fishers and at other shows, such as the International Sportsmen’s Exposition in Sacramento. He is also an author whose articles and fly patterns have appeared in this magazine, Fish & Fly, Fishing and Hunting News, and Western Outdoors. He also has pieces in or is featured in several books: Fly Fishing the Sierra Nevada, by Bill Sunderland, Go-To Flies (101 Patterns the Pros Use When All Else Fails), published in 2004 by Wilderness Adventures Press, and A Flyfisher’s Guide to Northern California, edited by Seth Norman and published in 1997 by Wilderness Adventures Press. He is also an excellent photographer, whose photographs have appeared in A Flyfisher’s Guide to Northern California, this magazine, Fly Fisherman magazine, and in the Sacramento Bee and Sacramento Union newspapers. On occasion, Ralph guest hosts a fishing and outdoors radio show on Nevada City’s KNCO. His other interests include his fly-fishing sons, Chip and Jeff, and collecting fly-fishing books. He lives in the California Gold Country town of Grass Valley.

Now let’s hear Ralph talk about his Pine Squirrel Leech.

“I started tying flies in New Hampshire at the age of 10, when my grandmother bought me an inexpensive kit that included a pressed-aluminum vise and a lot of colored feathers. Despite many years behind the vise, I really don’t consider myself to be an innovative tyer like Andy Burk or John Barr; rather, I visualize myself as a collector of various techniques that I’ve found useful in modifying existing patterns to suit my own uses.

“About three years ago, a rumor was floating around the now-defunct Nevada City Anglers fly shop about a fly that was fooling a lot of fish in the lower Yuba River. Since I guide on and avidly fly fish that lovely and productive river, I asked Tony Dumont, the fly shop’s owner, about the fly. Tony’s comments were that the fly appeared to be a small leech pattern with a red glass bead at the head, tied with a strip of mink body hair over the top and with a tinsel body. After perusing the materials section of the shop, I found no mink body strips, but soon located and purchased some pine squirrel strips in several colors and left for home to see what I could come up with at the vise.

“After some experimentation, I devised with what I call the Pine Squirrel Leech. The fly was an instant success on the lower Yuba. On the first day out, in a two-hour session, the olive version garnered three fish to hand and numerous strikes and hookups. I was fishing the fly on the swing using a 5-weight rod with a matching Hi-D sink tip. I later discovered that an intermediate line works even better, because the fly stays at the same depth for most of the swing, rather than rising, as it has a tendency to do when fished with a sink-tip line. Since then, I have tied the fly with black, natural, rust, and chartreuse squirrel strips.

“In July of that same year, some friends and I ventured to Alaska to fish the Copper River near its confluence with Lake Iliamna. After a couple of days of fishing the guides’ patterns for both sockeye salmon and rainbows, I decided to try a couple of my own patterns. I switched to an intermediate sinking line and tied on a Pine Squirrel Leech dressed with a black squirrel strip, a red glass bead, silver wire ribbing, and a silver holographic tinsel body. A few casts later, I hooked into a nice sockeye salmon, which I might mention was taken on the swing and hooked firmly in the mouth. So much for sockeye not being aggressive! This was not the only sockeye I hooked on the Pine Squirrel Leech that trip. Later, on the Copper River itself, I took rainbows and char on a Pine Squirrel Leech dressed in the natural color.

“Each spring, I anxiously await bass and bluegill angling. I’ve tried the Pine Squirrel Leech in ponds at the Spenceville Wildlife Area with pleasantly surprising results: both bass and bluegills have climbed all over it. The most effective version for this purpose is tied with a chartreuse squirrel-strip wing and a gold tinsel body. I use a 5-weight rod with a weight-forward floating line to keep the fly out of the ever-present weeds that grow upward from the bottom. A steady twitching retrieve does the trick.

“I later learned that the pattern was originated by Don Liljeblad, a member of the Gold Country Fly Fishers, of which I’m also a member. In a conversation with Don and after a subsequent exchange of flies, it was very apparent that my pattern bears no resemblance to his original. Don uses a scud hook, size 8 to 14, a black tungsten bead, and a tinsel body and mink hair wing and tail tied in halfway down the bend of the hook. He uses no dubbing; instead, he wraps the wing material that remains after tying in the mink strip at the hook bend forward to the bead to cover the thread wraps. Tony may have seen the fly tied with a red bead, since Don sometimes uses one to imitate a small Egg-Sucking Leech. To my way of thinking, Don’s fly resembles a spin fisher’s miniature “pig and jig” lure — a highly effective bug. Don uses the pattern for trout on the lower Yuba River and for bass and bluegills.

“Now that I have seen Don’s pattern, I chuckle at what happened and have decided to be a little more inquisitive before running off to try to duplicate a verbal pattern description. I will, however, tie up some of Don’s original pattern this spring and put them on trial in the bass ponds of Nevada County. Maybe it will work better than mine, and of course, I already have a few modifications in mind.”

The Pine Squirrel Leech is a simple pattern that calls for readily available materials and a few tying steps.

Materials List

Hook: 2X-long streamer hook, sizes 10 to 12

Thread: Olive 8/0

Bead: Small red, silver-lined glass bead (size to the hook)

Ribbing: Fine gold wire

Body: Gold holographic tinsel

Wing and tail: Olive pine squirrel strip extending about one shank length beyond the bend

Dubbing: Olive (or to match the wing color)

Tying Steps

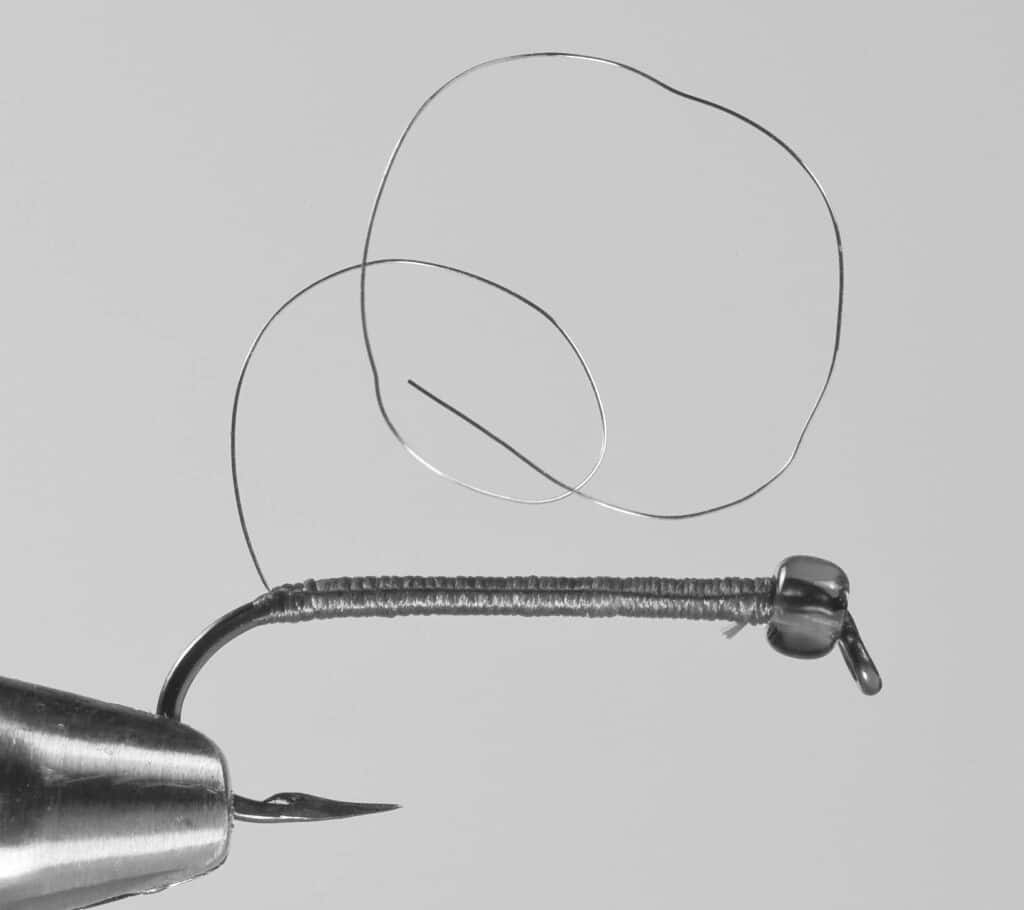

Step 1. Debarb the hook and slide a red, silver-lined glass bead up to the hook eye.

Step 2. Attach the thread directly behind the bead and build a small thread ridge there to hold the bead in place.

Step 3. Tie in the fine gold wire ribbing just behind the bead and secure it along the hook shank with close wraps of thread to a point directly above the back of the barb. Return the thread to the back of the bead, making sure that the thread wraps are even and that no lumps appear on the shank.

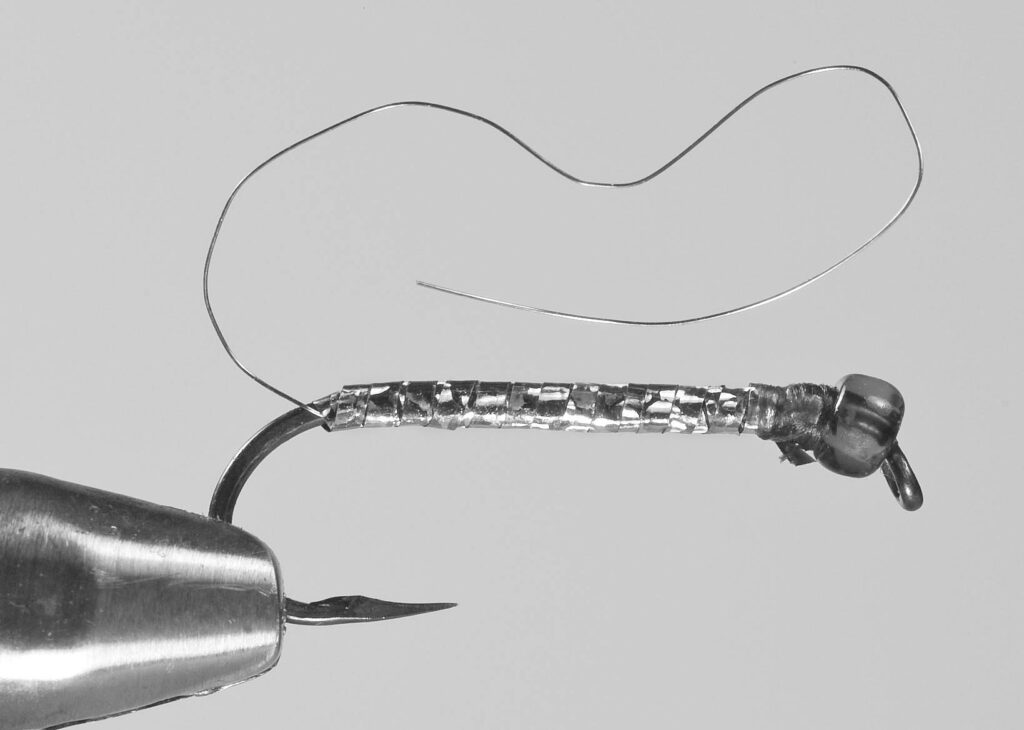

Step 4. Tie in the holographic tinsel behind the bead and leave the thread at that point. Wrap the tinsel rearward to the spot where the ribbing extends from under the thread, then wrap the tinsel back to the rear of the bead, tie it off, and leave the thread there. This results in a double layer of tinsel on the hook shank.

Step 5. Cut a two-inch piece of squirrel strip and tie it in close behind the bead, leaving the thread there.

Step 6. Stretch the strip rearward over the shank, then secure it atop the shank by winding and weaving the gold wire through it, using five to six evenly spaced wraps. Tie off the gold wire behind the bead.

Step 7. Twist some olive dubbing onto the thread and dub the area between the front of the squirrel wing and the bead. Whip finish directly behind the bead and apply a tiny drop of superglue.

Swing Ralph’s leech on the lower Yuba River using good mending and drifting technique, and wait for that swung-fly tug that keeps us coming back for more, and haunts our dreams.