During spring and early summer you may have noticed small, yellowish bugs flitting about on your favorite stream — sometimes in large numbers. If you are fortunate enough, you may even have seen the nymphal form of the critter crawling around on an exposed rock in or near the water. During evening’s prolific activity, I’ve seen many a fly fisher reach into the fly box and drag out a Light Cahill Parachute to try to match these insects — almost always with frustrating results, having mistaken these little insects for mayflies. They aren’t. They’re Little Yellow Stoneflies — also known to fly fishers as Yellow Sallies.

There are many imitations of adult Little Yellow Stoneflies, most of which, to be blunt, are plainly ineffective. They are either too bulky, built on too big a hook, or overdressed with flashy materials that look good to tyers, but perform poorly. In my experience, a fat lightning bug is not what the fish are keying on.

While I have my own patterns for imitating the adult, I tend to fish the nymph even during a hatch or during the evening egg-laying flights. Sometimes I’ll use an appropriately colored soft hackle as an emerger imitation, on a tandem rig with the nymph.

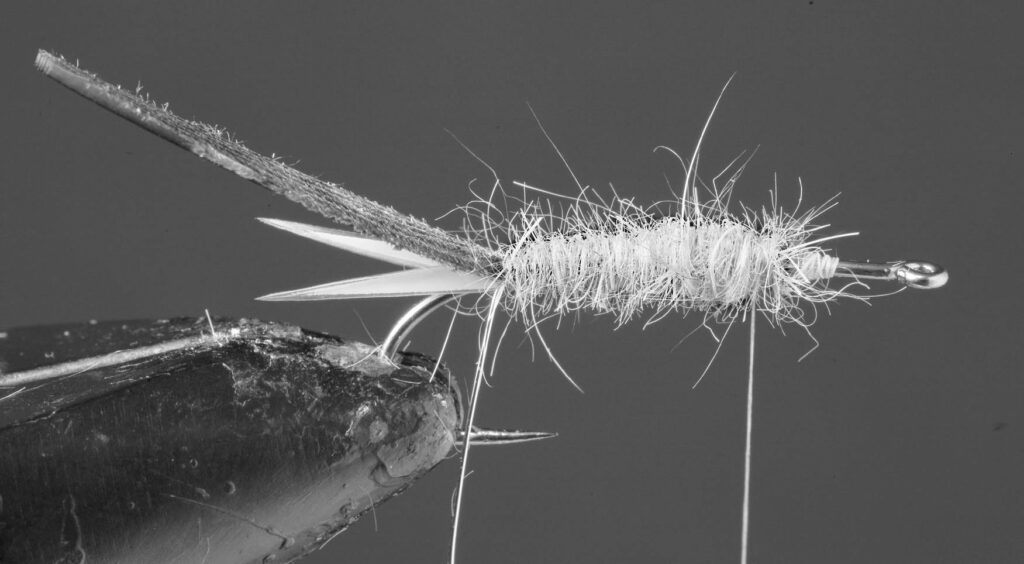

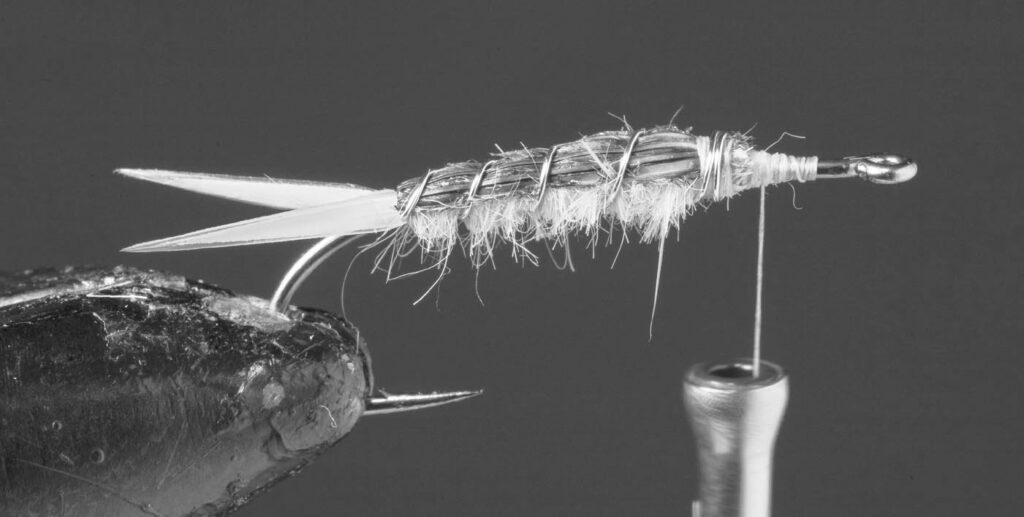

Because I gleefully spend innumerable days fishing and guiding on the small streams of the upper Middle Fork of the American River drainage, where Little Yellow Stoneflies are prolific, I see them in huge numbers. During this last season, on a midsummer day while fishing a small Middle Fork tributary, I found hatching nymphs on exposed rocks. Turning over submerged rocks in the same vicinity, I located migrating specimens and studied them carefully, comparing them with imitations in my nymph box. What I found was that my dubbing was the wrong color — not even close — and that my flies were far too bulky. The natural was slim and delicate, with a body color somewhere between light olive and yellow. The back of the abdomen and the wing case were dark brown and segmented, and the legs had a mottled appearance. My brightly bedecked yellow nymphs were destined soon to be undressed by a razor blade.

I captured a well-marked specimen and quickly preserved it. When I returned home, I searched through my tying materials, looking for finely textured natural dubbing in a yellowish-olive color with an eye toward creating the slim, delicate, tapered yellowish-olive body of the natural. After trying and rejecting a number of types of dubbing, I settled on dyed rabbit because of its dub-friendly soft texture and its slight translucency. For the back of the abdomen and the wing case, I tried thin turkey tail strips and Thin Skin (the Mottled Golden Stone color). For durability, the Thin Skin material is hard to beat, but still, the turkey tail won out in my mind because of its “buggy” look. (Admittedly, I have a bias toward natural materials.)

Spending that evening at the vise, I was able to crank out some decent-appearing nymphs, intending to use them the next day on that same small stream. When I arrived at my destination, though, my little stream was at flood stage. (I later discovered that the hydropower agency was engaged in a pulse-flow test as part of one of the studies in the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission relicensing process.) My tidy little test plan thus destroyed, I headed northeast to another small tributary that has mostly brown trout and a few rainbows. The nymph worked fairly well, but not as well as I had hoped it would. Since then, however, it has been tested on numerous backcountry streams and on the upper Sacramento River. The results have been gratifying, and I now carry a supply of the nymphs in various sizes and color gradations. I even carry a bright-green-bodied version — yes, there appear to be green adults scattered among the mostly yellowish-olive critters.

The adults generally return to the water in the late afternoon to lay their eggs, although I’ve also observed this behavior during the morning on warm spring and summer days. During this activity, delicate, sparsely tied adult imitations will draw vigorous surface strikes — but I don’t give up the nymphs until fish are taking the adults regularly and visibly.

Tying Materials

Hook: Daiichi 1260 or similar curved-shank, wide-gape hook, size 12 to 16

Thread: Pale yellow 8/0

Weight: .010-inch lead or substitute, four or five wraps at thorax

Tail: Biots dyed pale olive-yellow

Abdomen back: Thin strip of turkey tail

Ribbing: Fine gold wire

Abdomen: Fine pale olive-yellow rabbit fur dubbing

Wing case: Slightly wider strip of turkey tail

Thorax: Same as abdomen

Legs: Partridge

Tying Steps

Step 1. Smash down the hook barb and place the hook in your vise. Wrap four or five turns of weight at the thorax area of the hook. As an alternative to adding weight at the thorax, try using a tiny tungsten bead at the head of the fly. I generally prefer the interior weight, but a small, heavy bead is a good option.

Step 2. Secure the lead wraps in place with thread and a drop of superglue, then run the thread back to the bend of the hook. At that point, tie in the two biots for the tail. Their length should be about one-half the length of the shank. Don’t try to tie both of the biots in at one time. Tie one in on the far side of the hook and then tie a second one in on the near side.

Step 3. At the same point, tie in a thin strip of turkey tail for the back of the abdomen so that it protrudes beyond the rear of the hook, shiny side facing down. Be sure that there is no gap between the biots and the turkey tail.

Step 4. At the same point, tie in a piece of gold wire for the rib.

Step 5. Dub the abdomen with a taper that’s larger to the front. End the dubbing at the point where the thorax will begin, which is about one-third of the shank length behind the hook eye. Do not use excessive amounts of dubbing — the body needs to be slender. And before beginning the dubbing process, wash your hands. Even a small amount of dirt or other material on your fingers will change the dubbing’s color.

Step 6. Bring the turkey tail over the top of the abdomen and tie it off at the front of the abdomen. Trim the excess.

Step 7. Rib the abdomen and back with four or five turns of wire. Tie off and trim.

Step 8. Tie in a somewhat wider strip of turkey tail for the wing case at the front of the abdomen, again pointing to the rear of the hook and with the shiny side facing down. Be sure that there is no gap between the abdomen and the tied-in wing case.

Step 9. Prepare the partridge feather by stripping the fuzzy material from the stem near the bottom, leaving the stem intact, with about half an inch of barbules remaining on the stem. Then moisten the feather and, using your tweezers, grab its tip and sweep most of the barbules downward. This leaves a small “tab” at the top of the feather. Tie the feather in by the tab with the shiny side down (concave side up) and the butt end of the feather facing to the rear, directly in front of the base of the wing case at the same point that the wing case was tied in.

Step 10. Dub the thorax. It should be somewhat more robust than the abdomen, but still slender in appearance.

Step 11. Pull the partridge feather over the top of the thorax, sweep the barbules rearward, creating a set of legs, and tie the partridge feather down in front of the thorax, just behind the hook eye. Trim the stem.

Step 12. Pull the wing case over the top of the thorax and tie it down behind the hook eye (trim excess). This will cause the legs to assume a downward appearance.

Step 13. Form a small thread head and whip finish the fly. Place a drop of superglue on the head. For strength and appearance, the turkey tail on the abdomen back and wing case can be covered with a coat of shiny head cement or other product once the fly is completed.

When fishing this fly, remember that some (but not all) Little Yellow Stoneflies emerge in the stream flow, and not by crawling to the edge and emerging on rocks or streamside vegetation. Does that conjure up visions of a soft-hackle fly or what? (See the sidebar.) Bill’s Little Yellow Stonefly Nymph pattern is simple to tie and made from inexpensive, commonly available materials. Tie up a few skinny Little Yellow Sally nymphs, and . . . see ya on the creek!

A Little “Bugology” and a Few Angling Tips

The bug we know as the Little Yellow Stonefly is a member of the genus Isoperla in the family Perlodidae. These insects emerge in most years from late June through September. They’re widely distributed throughout the West. The nymph size varies between 6 and 18 millimeters (1/4 to 3/4 of an inch). The color of the nymph also varies from light yellow to olive-brown, but based on my experience, the predominant color appears to be yellowish-olive. As shown in the accompanying image, the nymph is slender and has dark stripes on the back of its abdomen.

Like most stoneflies, the nymphs prefer cold, well-oxygenated riffles and runs with a rocky substrate. Because they are active foragers, they are at times dislodged from the rocks. The predator then becomes prey as fish actively feed on them. Their emergence pattern follows the normal stonefly protocol of moving to the shallows, crawling out onto exposed vegetation or rocks, and hatching in the open. However, as mentioned in the text, there are some species that emerge in the typical mayfly manner by rising through the water column to the surface. Whether they are migrating to the shallows or emerging in the surface film, trout feed actively on them. The emergence normally takes place in the late afternoon or early evening, but this is not a hard-and-fast rule, so it is best to be observant and make a judgment call.

During an Isoperla hatch, anglers should not immediately step into the shallows. Instead, it can be productive to fish a lightly weighted nymph carefully and slowly over the rocks, because fish will move into the shallows to intercept the nymphs. If this tactic does not work, I switch to a deep-running rig and use normal short-line nymph techniques. I tend to stay with this rig until I see trout actively feeding on the surface. Most of the time, I add an appropriately dressed soft-hackle “stinger” with 16 inches of 5X or 6X fluorocarbon tied off the bend of the nymph. I allow the rig to swing as it passes my position, while slightly raising the rod tip near the end of the drift to suggest an emerging insect. This rig is also a good searching tool for the late afternoon, even if the nymphs don’t seem to be moving.

For more information, consult either Rick Hafele’s excellent article at http://www.laughingrivers.com/rick-yellowstones.html or Jim Schollmeyer’s handy little book titled Hatch Guide for Western Streams (Frank Amato Publications, 1997).

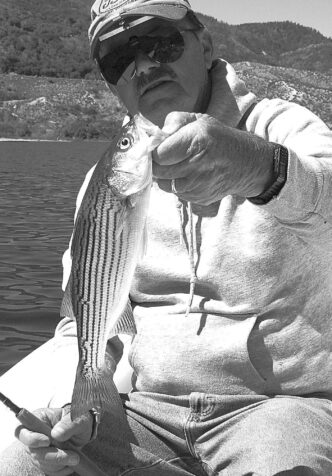

Bill Carnazzo