I met Ben Byng approximately six years ago. He had been recommended to me by a friend as an excellent and creative fly tyer who would be a good addition to the large cadre of tyers that, over time, I had recruited for the fly-tying How-to Center that I manage for the International Sportsmen’s Exposition in Sacramento. In selecting tyers for this gig, good tying skills are, of course, essential, but of equal, if not greater importance is the ability to speak respectfully and informatively to guests of the show who come up to the tying tables to watch a tyer weave together those delightful little miracles that fall from the jaws of our vises. I was told, accurately, as it turns out, that Ben has a gift for clearly and convincingly articulating the hows and whys of his creations. I found Ben to be personable, friendly, and knowledgeable as I watched him do his first turn in the How-To Center. He’s been a popular, consistent member of our team ever since then, often drawing large, enthusiastic crowds around his spot at the tables. I’ve tied flies with Ben at other shows, including The Fly Fishing Show in Pleasanton, California, and the Idaho Falls Tying Expo. He is currently the president of the Tracy Fly Fishers. I recently had the opportunity to attend one of that club’s meetings as their program presenter and was able to watch Ben deftly deflect (and return) the usual friendly heckling and jostling that goes on at such events.

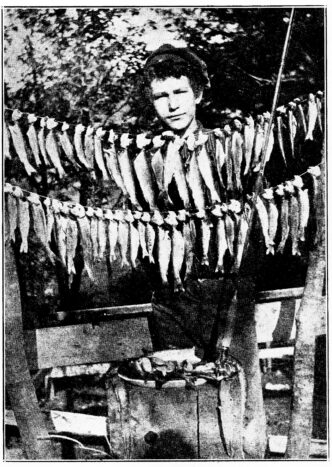

Ben brings a wealth of experience to the vise. Angling has been in his blood since he was a young boy. With his grandfather, he enjoyed fishing odysseys from the Great Lakes to the Florida Keys. With his father, he visited eastern Idaho during the summers for remote small-stream fishing and high-mountain adventures. These experiences armed Ben with lessons and lore that would follow him into his flyfishing and tying careers.

Because the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is in his backyard, Ben has spent many hours jamming in his boat through this 1,200-mile waterway, hunting down largemouth and striped bass. During the summers of 2000 through 2005, Ben helped André Puyans with his eastern Idaho fly-fishing seminars at Elk Creek Ranch, where he ultimately became operations manager. Ben is also an instructor for the Wilderness Unlimited and Becoming an Outdoor Woman fly-fishing clinics.

Ben’s fly presented here is a damselfly nymph imitation, and it’s constructed the way I like to see flies tied. I belong to the “tie ’em sparse” school within the fly-tying community — especially when it comes to tiny, delicate morsels such as damselfly nymphs. Because they are an important part of the diet of trout and bass that inhabit lakes and ponds, properly tied damselfly nymphs are of singular importance to stillwater anglers at venues such as Northern California’s Lake Davis. Yet despite the meager proportions of the naturals, many of the imitations of damselfly nymphs that are found in fly bins appear to be overdressed.

This point was hammered home to me on a warm June morning as I watched, amazed and mesmerized, as a slim, olive-colored, semitransparent damselfly nymph that had crawled onto my float tube transformed itself into an adult that, once filled with fluids, seemed far too large to have emerged from such a miniscule exoskeleton. This incident mimicked an earlier lesson in which I had observed a large dragonfly emerge from a much smaller nymph while I was sitting on a rock in the middle of the Rubicon River, eating my lunch.

So, when I saw Ben tie up a few of his Damsel Lite bugs, I knew he was onto something good — meaning that the imitation he was tying was one based on actual on-the-water experience, which to me is an essential ingredient in producing a fly that really, really works.

Recently, I was talking with one of Ben’s close friends about the Damsel Lite. We’ll call Ben’s friend “Joe” for anonymity purposes. It seems that Ben, Joe, and some other friends were at Lake Davis during the damsel hatch. Joe described the fishing as “slow” — we all know what that means — not just for him, but for everyone, including Ben. Puzzled by the dearth of willing eaters when fishing patterns such as olive damsel nymphs and the Red Rider and Prince Nymph, Joe furtively tied on two rust-colored flies — a Damsel Lite and a J. Fair Wiggle Tail Nymph. He rapidly began to experience ample “rod bendage“ on both flies, but lost the entire rig to a double hook-up on two strong bullies.

Bereft of rust Damsel Lites, Joe began the hour-long kick across the lake to bum some more from Ben, glad to have the time to plan his words carefully, lest he let the proverbial feline out of the bag. As Joe sidled up, Ben inquired of the quality of the fishing, and Joe, Solomon-like, replied, “Fair,” then departed with two rust and two olive Damsel Lites. Ben, it appears, did not notice Joe’s wry grin as he tied a rust specimen to his leader and kicked his way around the bend. Three fish later, Joe’s grin became first a giggle and then an outright belly laugh.

Later, as the group sat around the campfire, grilling s’mores and swilling Scotch, Ben popped the old heavy one: “Hey, Joe, what was the hot fly?” Glancing around at all the straining ears, Joe, not wanting to precipitate a shortage of Ben’s rust bugs, paused for a few moments and let fly with a doozy: “Rust Wiggle Tail.” I asked Joe how he slept that night after his willful prevarication. With a twinkle in his eye and a straight face, Joe replied, “Like a baby.”

Now let’s hear what Ben has to say: “The story behind the Damsel Lite is plain and simple. I could find no pattern thin and sparse enough to represent the delicate natural insect. In spite of my many attempts to find a way to wrap marabou around the hook and achieve the look I wanted, the outcome was consistently large, fuzzy bodies. These imitations not only failed to match the naturals, but they presented an entirely wrong physical appearance. I finally landed on a solution that worked. By simply tying the marabou butts in at the front of the hook, wrapping the thread rearward over the marabou on top of the hook, then ribbing the body with chartreuse Flashabou, I was able to produce the thin, greenish-blue, waxy-type body that I wanted.

“My favorite place to fish this fly is Lake Davis during the month of June on windy afternoons. The waters of Davis seem to draw in west winds that push damselfly nymphs off the east side weed beds and out into open waters. This provides anglers with the opportunity to cast up to the east side of the weed beds and strip the fly back in a short, erratic manner to mimic the swimming action of the natural. Floating and intermediate sinking lines work best, since the nymphs stay close to the surface. The Damsel Lite fishes well at other summertime venues when damselflies are present, too.”

Now let’s tie up a few of Ben’s little critters.

Materials List

Hook: Daiichi 1270, size 8, or similar long-shank, curved-shank hook

Thread: Olive 8/0 Uni-Thread, Montana Fly thread, or other thread

Eyes: Melted 30-pound-test monofilament or packaged translucent monofilament eyes in size “small”

Rib: A strand of fine chartreuse Flashabou

Body: J. Fair olive green marabou

Wing case: Olive Scud Back or similar transparent material

Thorax: Olive green J. Fair Long Shuck or similar product

Tying Instructions

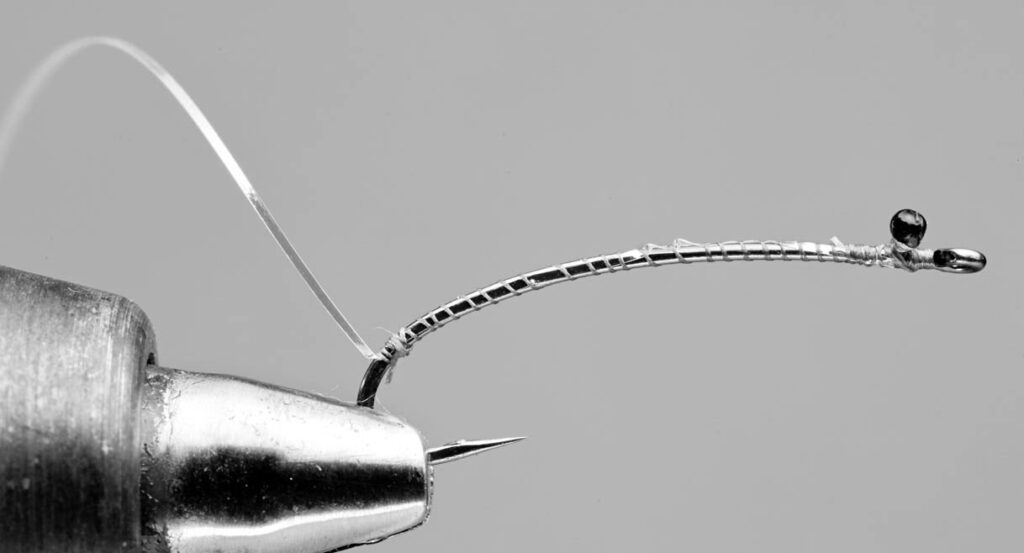

Step 1. Debarb the hook, place it in the vise, and start the thread behind the hook eye. Lay a sparse thread base on the front third of the hook and tie in a set of monofilament eyes on top of the hook shank, approximately one hook-eye width behind the eye. Secure the eyes with crossover wraps (sometimes called “X wraps”), followed by a series of tight wraps under the eyes and above the shank. This technique pulls the crossover wraps together and locks the eyes in place. Apply a tiny drop of superglue to the underside of the wraps. Using a black Sharpie magic marker, place a dot on the outside of the eyes.

Step 2. Tie in a strand of chartreuse Flashabou behind the eyes. Tie the Flashabou down all the way to the rear of the hook and a short distance down the hook’s curve.

Step 3. Return the thread to the rear of the eyes, maintaining a flat thread base. Cut a small clump of olive green marabou away from the feather stem and tie it in by the butts just behind the eyes, then trim the butts.

Step 4. Pull the marabou clump rearward and hold it in that position on the top of the hook shank. Tie it down along the shank by advancing the tying thread rearward in widely spaced turns to the point where the Flashabou strand is hanging. As you perform this step, try to spread the marabou strands around the hook shank. Advance the thread forward again in wide turns to the rear of the eyes.

Step 5. Rib the body with the Flashabou strand, tie it off behind the eyes, and trim the excess. Pinch off the marabou tips at the rear of the fly, leaving approximately a quarter of an inch to serve as a tail.

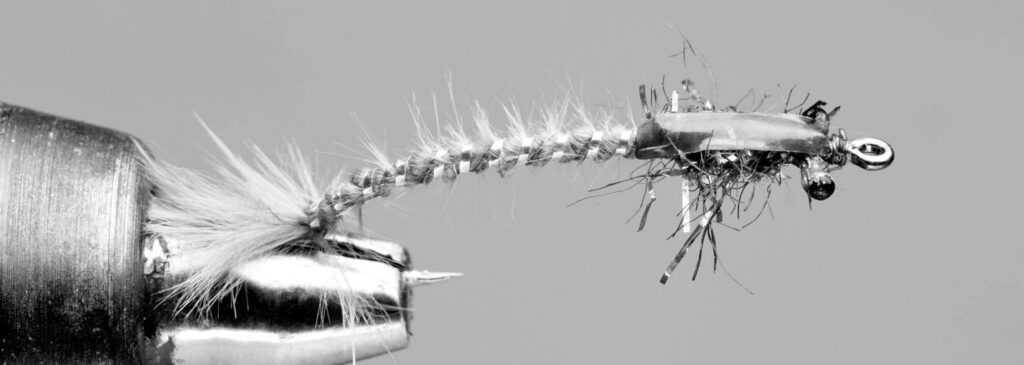

Step 6. Cut and tie in a short strip of Scud Back at the forward one-third point along the hook shank so that the strip extends to the rear of the hook. The strip should be approximately 3/16 of an inch in width. Leave the thread at that point.

Step 7. To form the thorax, cut and tie in a one-inch piece of the Long Shuck material at the same spot. Wrap the Long Shuck material forward using only two turns. Tie it off behind the eyes. Trim off the top and bottom of the Long Shuck so that the thorax has a flat profile.

Step 8. Advance the thread to the front of the eyes. Pull the Scud Back material forward with light tension, tie it off in front of the eyes, and trim the excess. Whip finish the head.

Follow Joe’s strategy of fishing both a Damsel Lite and a Wiggle Tail Nymph (or something similar). Sneak off to a likely spot where you can create a few stories for the evening campfire. But be sure to keep your camera handy for credibility purposes.