It had been awhile since I thought much about salmon. They were around, of course, especially during the fall, but never in the kinds of numbers that drew my attention from steelhead angling, that most bedeviling autumn sport. Now and then I encountered a big chinook or feisty coho, usually after I gave up on surface patterns, laced on the meaty Skagit head, and started swinging my 1/0 and 3/0 marabou-winged Spey flies, but these were dark, late-season fish, not salmon I would target, much less kill.

All anadromous fish are interesting to catch. Their life histories give them the appropriate degree of mystery, and for many of us, sea-run fish offer the chance to hook our biggest fish of the year, if not also of our careers. Still, it’s difficult to remain too excited after landing a fish, however big, that looks a lot like a worn-out pair of Levi’s — and when you see the lead weights and psychedelic bling the gear guys use for salmon, you can be excused for sidling out of the scene and retreating, say, in search of a pod of spirited trout worrying a late-season hatch of BlueWinged Olives.

Plus, there is the sense these days, true or not, that salmon runs everywhere have declined to the point that one more perfect storm may send local populations plummeting into the abyss of extinction. Do they really need my flies contributing yet another tug on the thin thread of their existence?

But last year, all of that changed. What started as the usual trickle of returning fish turned into an unprecedented flood. By September, tens of thousands of salmon were swimming in the river right below my house. For awhile, I remained keen on steelhead, out of habit, if nothing else, until one morning — after getting blanked through a favorite run — I decided to see if maybe I could find one of these salmon everybody up and down the river was, by now, talking about.

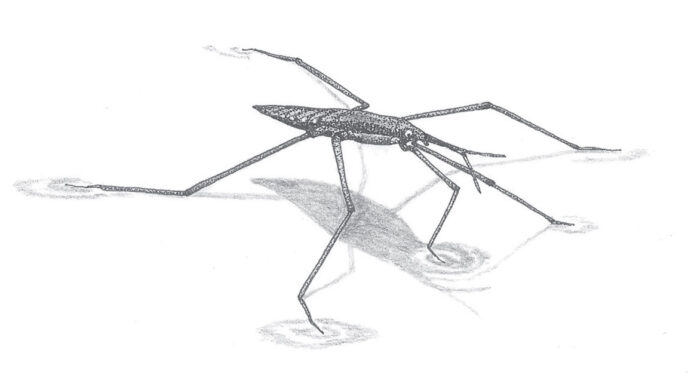

But how? Fly fishing, we all know, is never as simple as the decision to target an unlikely fish that suddenly appears within reach of a cast. And salmon, of course, pose their own host of challenges: What do you use for a fly for a fish that no longer eats?

Or do they? And if so, what?

And if not, we’re back where we started.

Which is how, perhaps, I came to tie on a pair of big stonefly nymphs. I say “perhaps,” because at that moment, I was more concerned with how I was going to go about catching a salmon than with any pattern that might do the trick. Readers of this column will recognize the tack. Despite the promise or reputation of any fly, I invariably return to my original thesis: it’s presentation, not patterns, that catch fish. What I tied to the end of my tippet, and also to one of the tag ends of the Blood Knot between tippet and leader, weren’t big stonefly nymphs so much as they were, simply, big nymphs — versions, in fact, of the 20-Incher Stone, a trout fly I wrote about in this column last year. (See “Kaylee’s Stone, Plus or Minus,” in “At The Vise,” California Fly Fisher, July/ August 2013.) But the patterns themselves seemed entirely beside the point. With a pellet of split shot pinched to the tippet halfway between my flies, my hunch was to nymph up a salmon.

Half a century lost to this silly sport has convinced me, among other things, that the shortest route to a hooked fish remains what I consider the oldest trick in the book — a couple of sunk flies led on a tight line through an obvious lie. Floating line, long leader, no indicator. Variations on the method are many, and the technique gets named and renamed again and again. But it’s the same candy bar, regardless of changing wrappers. Get down to where the fish are. Establish contact with your flies. Your rod tip, moving, travels one iota ahead of your flies. Read your line. Do what it tells you to do.

It’s as basic as fishing a worm. And usually just as deadly. The longer the rod, the better, as you want to lift as much line as possible off the water, reducing the play of currents on both leader and fly. At the same time, the last thing you want to do is drag the fly through the lie or do anything that restricts or changes the fly’s natural course.

The Profound insight about this basic fishing technique is that it’s essentially the same way that you swing a surface fly through a steelhead run or a soft hackle through trout water, and if you can make that connection between these seemingly disparate methods, you’re well on your way to understanding the principles that apply to nearly all aspects of presentation.

Easier said than done. I can’t count the number of times I’ve stood next to friends or students and failed to get them into fish while they try nymphing through a proven lie. Time and again, I think they’ve got it: their casts land just right, they pick up the slack off the water, flies appear to travel perfectly through the slot. But nothing happens — no take, no grab, no sudden, thudding jolt just at the moment you thought you might be hung up on the bottom.

These days, I refuse to touch the rod in these situations. I can make as many mistakes as the next angler, but given a couple of good-looking nymphs and a little split shot on a likely piece of trout water, chances are, I’ll find something. For students, nothing is more discouraging than running a nymph through a slot for 15 or 20 minutes, then having the teacher take the same rod and reel and fly setup, stand in the exact same spot, and immediately hook a fish. Nobody likes that. If it’s your sweetheart you’re fishing with, you’ve probably really blown it.

Still, short-line or tight-line nymphing — or whatever you want to call it — is part of a long and often frustrating learning curve. Then again, at some point, you just get it. Unless the only reason you go fishing is to catch fish, you probably won’t become a full-time nympher, no matter how effective the technique may be, but from the point you master the basics of fishing weighted flies with split shot on your leader, you’ve got that to rely on, should all else fail.

I insert this long digression on the basics of nymphing because I want to impress upon the reader the idea that more times than not, catching big fish — even salmon — is not about having the right fly. Intent on nymphing for local chinooks, I tied on a pair of flies that I know how to fish in a particularly effective manner. I waded in up to my knees, lobbed a rod’s length of line and leader upstream, and as the cast followed the tip of the rod, I got an idea how deep I could fish in how much current, whether I needed less weight or more, how far I could swing into the soft water before tangling with the bottom. By this time, I wasn’t even thinking about my flies anymore — a subject that does you absolutely no good to consider once you step into the river and start casting.

I wouldn’t share all this, of course, if none of it worked. What surprised me, however, was how much the salmon liked a big stonefly nymph — or were at least agreeable to eating one. Within two days, I had the smoker going full time, and I was passing out salmon filets to folks who had been sharing summer produce from their gardens, the kind of thing that happens with increasing frequency to a single man approaching his dotage. At the same time, I began refining my nymph, transforming it into a pattern that I wanted to believe proved more and more effective as I beached more and more fish.

Maybe. By the end of the salmon season, I was calling the fly the Anadromous Stone — but when I sat down at the vise this summer in anticipation of what was predicted to be an even bigger run of salmon, I was struck by how much my “refined” pattern looked like the trout fly, Kaylee’s Stone, that I went on to describe in that column last year. There were definite changes, though, and I was sure that never before had salmon taken the fly so aggressively, strikes that felt exactly like feeding fish. “They want it,” I claimed to no one else in the kitchen, spreading smoked salmon mixed with cream cheese on a shingle of Rye Krisp bread.

I was reminded, anyway, of a classic line once spoken at the Tyer’s Roost: All nymphs are Hare’s Ears, they’re just tied with different materials. But with the Anadromous Stone, I wondered, did I finally hit on some magic combination, one that salmon can’t refuse?

You know the answer. Rather than the Right Fly, I happened upon a pattern that worked, one I came to believe in when fished in a manner I trust in a spot that I knew held plenty of fish.

That’s the real combination, right there.

Materials

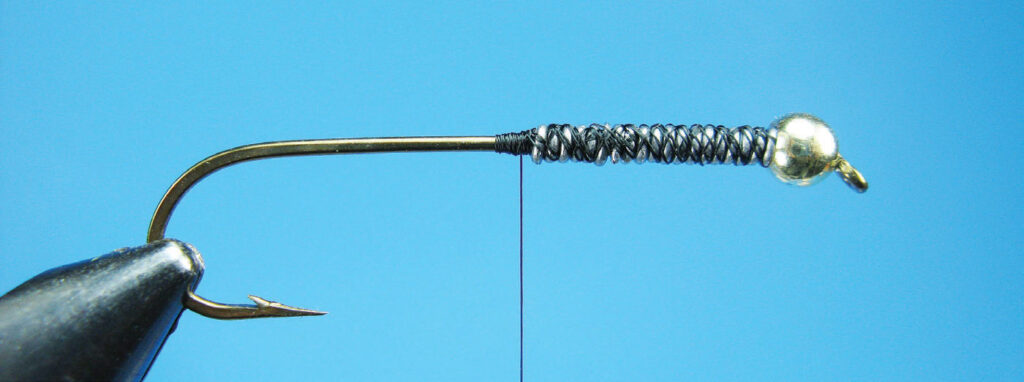

Hook: Mustad 79580, size 2 to 4

Head: Gold 3/16-inch brass bead

Weight: .020-inch lead wire, 15 turns

Thread: Black 6/0 Danville Flymaster

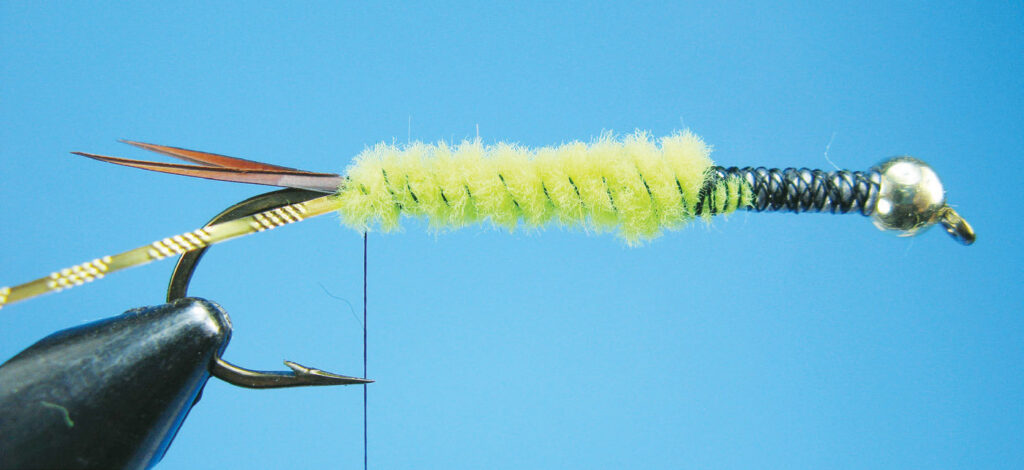

Tail: Dark brown goose biots

Rib: Medium flat embossed gold tinsel

Underbody: Medium fluorescent chartreuse chenille

Abdomen: Peacock herl, spun into copper wire dubbing loop

Wing case: Turkey tail feather

Legs: Brown round rubber

Thorax: Medium purple or orange chenille

Tying Instructions

Step 1: Slide the bead over the point of the hook (you may have to pinch down the barb) and up to the hook eye. Secure the hook in the vise. Wrap lead wire over the front third of the hook. Press the coils of wire tight to the bead. Start the thread and lash the lead wire so that it doesn’t spin on the shank.

Step 2: Wrap the thread back so that it hangs near the point of the hook. Hold a pair of goose biots back to back and align the butts with the hook shank. In order to get the biots to sit correctly, start with the pair held about a quarter turn in your direction, take a couple of loose thread wraps around the butts of the biots, and then allow the biots to spin into place as you continue wrapping your thread. Anglers claim that fish don’t inspect the tail of your fly. However, as an old surfer, I believe that the rigid biots affect how a fly travels through the water, and I aim to create a profile that remains in trim while riding the current.

Step 3: Secure the tinsel ribbing at the root of the tail. Then tie in a length of chenille for the underbody. Wind the thread forward up onto the rear portion of the lead wire. Wrap the chenille forward to the same point, tie off, and trim the excess. Spiral the thread back around the underbody to the root of the tail.

Step 4: Create a dubbing loop with a length of copper wire. Insert the tips of four or five strands of peacock herl at the top of the loop and spin your dubbing-loop tool at the bottom to form a rope of herl and copper wire. Advance the thread and follow with the herl and wire rope to form the abdomen of the fly. Because these are such big flies, you may have to repeat the dubbing-loop process halfway up the abdomen. The abdomen should end about a third of the way back from the head of the fly. Then spiral four or five open wraps of the tinsel rib from the root of the tail over the abdomen and secure it just ahead of the abdomen.

Step 5: Clip out a half-inch wide section of turkey tail feather. Tie it in dull side up by the tips of the feather directly in front of the abdomen, butts facing to the rear.

Step 6: For the thorax, secure a length of chenille directly in front of the tie-in point for the turkey wing case. Then wind the thread forward, pausing twice to tie in lengths of round rubber for legs. Advance the thread to just behind the bead.

Step 7: Wind the chenille forward, wrapping between the pairs of legs to keep them evenly spaced. Tie off the chenille directly behind the bead.

Step 8: Pull the turkey feather over the top of the thorax. Tie it off directly behind the bead, clip the excess, and cover the clipped end with thread wraps. Whip finish and saturate the exposed thread wraps with lacquer or head cement.