My cardiologist leans against the kitchen counter watching me whip finish a fly. He’s pretty sure this knot is the same as or similar to one he uses during an operation I don’t need, but it would be bad form for either of us to mention that someday I might. There’s something else on the agenda today. He wants to learn about fly fishing, and I’ve agreed to teach what I know, however limited, bent, or wrong that knowledge might be.

Most fly fishers will find themselves choosing to do something like this — or not. To the great benefit of most of us fishing now, tens or hundreds of thousands have already taught the curious, the tentative, the newly obsessed … have taught us, early on, in short. Others have declined, with true modesty leading the reasons they demur, I suspect.

I’ve done both a fair number of times, but probably evaded more often than not, usually offering a “Sure!” that meant anything from a genuine “I’d sure like to” to “Someday, maybe,” and once, “Sorry, pal, but this urinal next to yours was the only one open when I walked in.”

This much I can say, however: other issues aside — as in “How else can somebody learn?” — I’ve had a lot of fun instructing people as well as I can and have so far inflicted less damage than when I sing Irish drinking songs in a public place. (Man, but some of those Irish folks are sensitive to tune.)

Which brings us back to Rob, my cardiologist. Rob — he insists I call him “Rob” now — is a thoughtful, soft-spoken guy, the antithesis of an arrogant cartoon doctor. I believe his daughter is seven now. I’m sure his son is ten, because he was eight two years ago, when Rob first spoke about taking him fly fishing. That was about a year after we started scheduling my appointments at the end of the day, the better to talk about families, long-distance biking (his; I am sane), writing, teaching, the machinations of Big Pharm, and other changes in health care. We get along because we’re both sentimental sorts who share a certain wonder at the way the world works. If we were frogs, I’ve thought, both being swallowed by snakes, we’d have a lively chat about back-leaning teeth, expandable jaws, and “Those eyes! Look at ’em! Would you invite eyes like those home to dinner? Ha!”

Along the way, we’ve learned that his cardiology mentor and idol was a guy with whom I shared a sandbox in 1957, also a partner in high-school misdemeanors on which the statutes of limitation have all run out. When fly fishing first came up, Rob mentioned that his father does a little, between botanical adventures. Next appointment, Rob hesitantly confessed he’d like to try, always had, and also to teach his son, then eight, as noted. I promised to take them the winter before my boat died, which kiboshed that plan without voiding the intent.

Even so, I suppose this might have gone on indefinitely, except for the events described in what follows.

Back to the vise in the kitchen. Rob’s son isn’t there, but Rob is determined to take home today’s lesson, which likely explains why he pays such close attention as I show and tell him how and why he will now tie this, his first fly, which he’ll fish in an hour or two.

The basics:

“So we’re hoping to catch cutthroats, beautiful natives. But there’s also a few stocked triploids in this lake, up to twenty inches, and I figure you wouldn’t mind tagging one of those.”

“That would be great,” says Rob. Then, in a wistful reference to his only flyfishing experience, a week he spent trying to teach himself, “Because I sure couldn’t catch any big ones in Montana.”

“Yeah, well, Montana fish get kind of snooty,” I explain, “hanging around with those high-priced folks. But here, with those cool days last week, the fish where we’re going will be feeling fall, feeding hard, looking for big meat. And it happens this lake’s also full of leeches — fat leeches, this late in the season, so this fly is . . . ?

I hand it to him. “A big, fat meat leech?” “Exactly,” say I. “BFML for short.” “Really?”

“No. Or yes, I guess, because it’s an oddball variation of two or three patterns I can’t remember, so we can call it anything we want. What’s important is . . . leeches undulate when they swim, right? Which is why we use these soft fibers and feathers that smooth out in water, and pulsate . . .

“. . . we want to add weight, to get the fly down, and to create a jigging motion . . “. . . and because triploids are rainbows, more or less, stocked rainbows that are fools for red, we’ll add that weight with this red bead . . . ” And like that.

“So now it’s your turn.”

I’ve never done this before, leading a novice from vise to water directly. But I’m sure others have, and it seemed like a good idea when I got it, providing concrete, hands-on illustration of points otherwise abstract while producing something Rob can hold in hand and then cast posthaste. Of course, the best laid plans gang oft to Hell, so I try not to offer too much information at once; or, soon failing that, to sound less pedantic than I am in real life. Ah, well. But Rob’s an excellent student, and I do love to teach. He starts with a tail of mixed marabou plumes — brown, olive, a little yellow — laced with a few strands of Flashabou. To this he adds a body of seal-something dubbing — he manages — which he proceeds to rib, rather neatly, with copper wire. Comes a pheasant feather laid flat, then another hackled twice and tied down so that lemon yellow barbs sweep back to the hook barb. (That could be a hard part, but isn’t for Rob.) Right there I feel obliged to demonstrate the whip-finishing tool I’d forgotten, but Rob disdains this for a sort of suture move that sews everything tight. He’s happy. To the untrained eye his fly looks almost like mine. Since I’ve only a faint idea how a trained eye would see it, I agree and, overwhelmed by pride, offer him lunch. Naturally, the turkey sandwich is low in cholesterol, so he’ll think well of me, but with just enough sodium — say a three-day supply — that he won’t think I’m trying to con him.

“Great, thanks,” he says, then looks at me expectantly, meaning either “Is that pumpkin pie I see over there?” or “Can we go fishing now?”

Yes and probably. I’m about out of options: before we tied flies I checked Rob’s tackle and casting. His rod’s an off brand, but sweet, very sweet, and surprisingly well matched to the line that came with the outfit. The reel also balances, and like most of those built for trout these days, sports a drag sufficient to land a tarpon, an AFL team, and most older Honda Civics. More importantly, his casts lay out pretty well, all the better for a tip or two, and much, much neater once I replace a leader that looks like relic from a culture that counts goat herds by tying knots on a string. (“I figured that was a problem,” Rob said sheepishly.)

We eat pie.

“If you’re finally ready,” I say.

Actually taking a novice fishing is where things get dicey — a serious consideration, this. As a general rule, the first time you think you’re experienced enough to guide, you’re ten years premature. On the other hand, everything’s relative. If you’re wise enough to know what you don’t know and candid enough to admit all that, you’re good to go this very afternoon.

We pack the car. As I turn the key, I tell Rob that the trip’s half a success already, because we haven’t yet broken a rod.

He doesn’t quite get this, but someday he might.

It’s details like that and the 400 more I add as we’re driving that mean so much, I’m sure. I believe half of these helped Rob to recognize a kind of conundrum inherent in fly fishing; also, by extrapolation, evolution, Thai cooking, religion, and all the astrophysics I understand. Here it is in executive summary: we seek to understand secrets of a vast natural world, from tiny lives of benthic organisms to the complex exigencies of fish, including the ineffable — ineffable! — influences of season, temperature, spawning cycles (“Did I miss that turnoff?), and half a hundred — or a thousand! — other phenomena. To this encyclopedic knowledge we add keen, immediate observation, physical skills developed over time . . .

. . . and in my case, bathos, the unexpected descent from the sublime to the ridiculous that helps out a bunch when you’re about to balance all the above on a scale opposite the unknown weight of dumb luck, aka “blind,” “rotten,” or “lousy,” but rarely “good” because we take credit for that kind.

Of course, all this was merely an affirmative way of saying “I’m doing my best, but we might not catch anything, OK?” (I knew this wasn’t a necessary caveat with Rob, but you don’t want to takes chances with anyone who can have you catheterized on a whim.)

He looks alive as we park, improves while we offload, and is so jazzed as we pack up to pack in that he offers to carry three rods, both oars, all sundry gear and — I kid thee not — my wallet and car keys. I’m a little alarmed — he’s my cardiologist; is there something he’s not told me? — and profoundly offended.

“I can carry my own keys, you know.”

Those oars will row a small plastic boat locked to a palette near the launch of a lake fished in these pages before — a big pond, really, shallow and weedy, completely surrounded by tules that fade into meadows and woods. It’s quite a pretty place, today without another soul around.

The sky’s a pleasing blue between pale streaks of cirrus clouds and puffs of low cumulus, if that’s what they call the fluffy ones; air and water temperatures are perfect, and just the right sort of breeze ruffles a surface where nothing, absolutely nothing is rising.

I don’t let this worry me. Ditto the fact that once in the water we’ve got two inches of freeboard at the stern and, I happen to know, a slow leak.

I will row, of course, despite Rob’s offer. “I’m fine, really. The keys weren’t as heavy as I thought.” He bunches up in back, looking no more alarmed than justified.

“The channel’s there,” I say to distract him, then stroke. “Running up along that side,” stroke, “but this area’s a flat that,” stroke, “won’t turn on till dusk.” Double stroke for the period. “That’s why I’ll pull us across,” raise oars. “That’s your fly tied on, and you’ve trolled before.”

He has. But it’s a different game with a fat line that floats, harder to maintain tension; he misses a strike, maybe another because of slack. I offer advice about how to maintain tension, when to expect strikes — “when I straighten up after a turn.” Also, “The hook’s a little big for the smaller cutts, but not for the fish you want.”

Another whack missed 100 feet along. I’m pleased that Rob’s less frustrated than puzzled. I’m also pleasantly surprised by so much action: this lake can be moody, even mean.

Rob raises his eyebrows, as in “What am I doing wrong?” I grin. “Tension. Keep tension. But think…three fish just tried to eat a fly you tied.”

He likes that. “That’s right. Man . . . that would really be something to tell my son, if…”

Wouldn’t it, though?

Contrary to the evidence above, I don’t talk much when I’m on water. Not for the first few hours, anyway. I forget that this surprises people and don’t remember while I pull us almost to the far shore, close enough that the surface lies flatter in the lee. I stay silent and still when

I see a fish rise a hundred feet away, then ship the ship the oars as a second does a slow head-to-tail not forty feet out. Sipping midges from the film, looks like, but the size of the dorsal fin suggests it can eat whatever it wants.

“Big fish,” I hiss. “Big fish.” “You cast.”

Not a chance. “No no…take it slow, wait for the rod . . . oh, that’s verrry nice.”

And it is — a cast that drops the fat fly lightly at the end of line and leader pulled straight. A tad short, or maybe not. . . . “Let it fall just a — now strip, slow, strip . . . ”

Wwisssht.

Rob’s strike is perfect. That sweet rod doubles. The fish boils; it is the big one, or a beast the same size. It runs, thrashed through the surface, runs, doubles back, runs again — “Tension. Tension” — and every time Rob keeps the line clear.

I’m pretty sure he hasn’t exhaled since the hook set. Now he does, softly, all at once. “Look at that . . . look at him.”

“Yes. Good . . . slowly ”

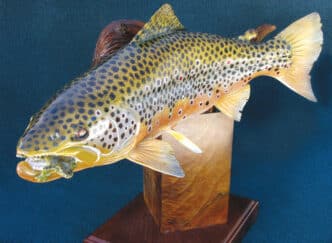

It’s all that twenty inches. As big as any that baffled Rob in Montana, turns out — a whole lot larger than any he imagined we’d see.

Me too. So I’m laughing. “And this,” I say as I lift, “is a triploid rainbow that thought it was eating?”

“A big, fat meat leech.”

I forget rob put the camera in his pack with my wallet. So does he. I shoot a quick pic with my cell phone, one more, then revive the fish. Rob has leaned over as far as the freeboard allows. He can’t wait to tell his son and his dad.

Not too bad, you know? Also, not too likely, right?

I grin again as I emphasize this, best laid plans and all, luck on the scale. We should probably go home now, because the day can’t get any better. But we don’t, and it does.

You get one now and then. That was the only triploid, but the cutts come out to play, gorgeous and larger than most years, if still under a foot. The pace keeps us engaged for hours with just enough breaks to talk about other things.

One of which was teaching.

“You’re not going back to the college?” he asked.

I shrugged. “Doesn’t look like it. They’ve had more layoffs since I left. Pretty random, all over the place.”

“That’s too bad. I know you liked that a lot. ”

“I did. I really did.” “More than writing?’

I laugh and hold out both hands to weigh. “Big stocked triploid? Beautiful cutt?”

“You know, I was just going to say I like catching them both just as much.”

Rob came up with that all by himself.

We stayed till dark-thirty, navigating back to the launch like blind mice. Had a drink when we got back to the house and were heading for another when a wife called. The pictures of the triploid were . . . shoot. . . just enough to give Rob’s son the idea. “We’ll just have go again,” I texted him. Maybe Saturday. . . .

A day or two after our outing I ruminated about how it happened — the small spark that ignited, at last, years of warm intent.

“Ruminated” is not the word. I entertain myself:

Six or seven weeks earlier, an ordinary annual exam with a new GP triggered the most astounding series of follow-up exams that would prove mostly unnecessary. Within weeks of the original strip search, complete with palpitations and appalling intrusions, I’d also been echoed, X-rayed, remedicated, repeatedly bled and injected, biopsied, freeze burned and sutured, interrogated about lifestyle, ontology, and attitude, remedicated again, and subjected to hundreds of (alleged) beeps I couldn’t hear in my left ear. I don’t know who was more exasperated, me or my HMO.

The last of these test procedures was an MRI I liked least of all, since “stay still” isn’t my forte. If you’ve done one, reader, you too know how four hundred generations of hamsters have felt when shoved into Easy-Bake Ovens — not as hot as that, maybe, but much louder.

I’m not sure how many days I spent in that tube. (The tech lied.) But I do know I emerged dazed and confused, medium rare, (more) deaf, and done. “Enough!” I said to myself as I staggered to my car. I repeated this several times, since it was still hard to hear anything. Not to sharpen that point, but I assumed the first three rings of my cell were tinnitus.

“Rob,” he said when I answered. I think that’s right, but since I remained silent while pondering “aw,” the only sound I’d heard, he added “Your doctor, the cardiologist?” He followed with good news about the (unnecessary) echocardiogram, assuring me I have the heart of champion, although not in those words. Then, “So, how’ve you been?”

I offered him an abbreviated litany of the outrages his industry had inflicted upon me, grudgingly noting that I didn’t hold him completely responsible. Rob assured me that, at least locally, doctors don’t own the kinds of labs to which I owed copays equaling airfare to Belize.

“Actually, they can’t. It’s against the law.” “That may be,” I said darkly, “but I’m

still going fishing.” “Good idea.”

Bang, it hits me. “And . . . you know what? You and your son should come.”

“Really?”

Almost an accident, in other words.

Now, finally, for that next, deliberate, follow-up Saturday trip . . . let’s go back to best-laid plans.

The Friday before, my guts began to twist. Clutch, really — small spasms, soon about half a second apart.

Nasty, but I’d been here before, although it was never before quite this bad — an annoying, common condition that vanishes in a couple of hours.

Five or six later, I double-checked diagnosis and prognosis on the Internet. Again at midnight, then two-thirty. I read that the locus of pain, if you could find one, would be on the left — an observation that I thought rather wry, like suggesting you identify the impact of one knuckle in a fist punching you hard in the head.

By dawn, things had changed some, not for the better. By nine, I noticed my mood getting “tetchy.” Came noon, and I found I was tender . . .on the right side.

Say what? No no That can’t be —

To all the tests add a CAT scan “with dye,” which at that moment sounded like the last thing I needed IVed into a vein.

“You’re pretty old for acute appendicitis,” said the ER doc who brought the results. He sounded a bit miffed.

“You’re right,” I croaked. “I’m so embarrassed. How about you write me a script for antibiotics and I go home right now. We’ll forget all this happened.”

“Yeah. That, or we’ll operate in two hours.”

Clearly, the man was an extremist. But I try to stay flexible, when I’m doubled over like that.

I’ll spare you the details.

I swam through Sunday. Mid-Monday morning, my old dean called right out of the blue. It had been a while, and I tried to remember if she usually spoke through puffs of cumulus clouds, all those pretty colors floating up from the bottom of . . . the Marianas Trench?

Could I teach two classes, beginning next week?

“Absoluuutely,” said the Percocet and some other pill, in a voice that actually oozed. “I’m pleazzzed. I’mmm delight-tata-ted. I’vvvve been thinking about howww much I mizzz teaching.”

In fact, why wait a week? If she wanted, I could be on campus by “noooooon.”

“Are you . . . all right?”

I explained. She sounded a wee bit doubtful I’d be ready in time.

I wasn’t, and I was.

That did leave out Rob’s next lesson and left him with only a “suggestive” photograph. But he seemed to understand, even offered to help if I needed anything. In fact, I’m so confident of Rob’s that I know he’ll forgive me if anything untoward happens next time I’m in his office at the end of the day. Say,

theoretically, that he has to chase me into the parking lot if anybody says or coughs something that sounds like “cath . . .”

But I’ll talk to Rob before that appointment, because I want to, and maybe to squeeze in another lesson between classes and columns. It’s better we do this while he still wants to catch and tie things I know something about; if he ever decides he’d like to “marry” wings for an Atlantic Salmon fly, I’ll have to bow out, saving face by muttering about “religious issues” and “unholy barb interbreeding.”

Ah. And then there’s the issue of Rob’s first fly, and his finish knot. Because while it’s hard to tell with laparoscopy, and not all docs may tie the same way, but from the one stitch I see, it just doesn’t look whip-finished. And since he’s likely to fish that BFML next time, he might want touch up the head with a little cement, sniffed only by accident, in moderation.

So for those too modest . . . you really might find this teaching stuff as much fun for you as it is valuable to others. More, maybe.