Traveling solo, fishing solo, strips from you the protection, comfort, and occasional trials of a comrade, along with some of the insulation that lets you travel through wild and peopled worlds with minimum drag. You’re approachable, for better or worse, and for warier folks, less imposing when you approach them. It’s a fine way to learn something unexpected, fish wherever you want, sleep whenever, and eat foods that offend ordinary mortals. Once in a while, it also reminds you that, in the aching words of Carson McCullers, the heart is a lonely hunter.

I’m south of Oceanside, weary and dirty after a day spent remodeling la casa su mi madre, an old mobile home now a bright, new bungalow. Labors of love are still labor; I deserve an hour of angling in the fading light.

That’s about what I’ve got left. I took too much time scouting beaches from Encinitas north; now, here I am at the top of a traditional range I started staking out in 1973. Oddly enough, though, I’ve never investigated the estuary I see from this new parking lot, built on a low bluff above a wide lagoon. The latter’s access to the ocean is by a knee-deep stretch of stream, but if its flow is the only egress and ingress allowed on this rising tide, one of the highest of the month . . . ?

Just west of me, low surf rolls high up a beach lightly trafficked by strollers and joggers, a kite flyer, couples holding hands as they mush through heavy sand. A forest of masts rises from the harbor just north, now so built up from the last time I fished here that I couldn’t find my old spots without Sacagawea and scouts.

But I did recognize the rock wall where one day in 1973 I grabbed an octopus and an octopus grabbed me. We did the dance that coy phrase suggests, exchanging leads as its tentacles twined past my elbow while I sang a high-pitched solo anticipating the bite of its black-beaked castanet.

I think I recognized that wall, anyway. Below me on the bluff, on the opposite side of the shallow outlet stream, stands a rangy fellow in street clothes. His long sleeves are wet to the elbows, long pants soaked to the knees; sopping leather shoes deform around his feet. Water drips from a stone he holds as he watches me with what certainly looks like expectation. I wait, staring back with a raised eyebrow or two. He nods acknowledgment. “Over there,” he calls softly, pointing to where the stream meets the estuary mouth. “If you want big catfish, over there.” He spreads his hands two feet apart. “They’re taking food off the surface of the water.

Tuna and seafood salad.”

Sometimes even simple sentences take a moment to digest. It doesn’t help when he adds “But they like old tortillas best. ”

Well, that covers basic food groups, I think.

Just then, a wave pushes up the stream into the lagoon, widening out as it passes across the bar at the mouth. Ten feet beyond — now that was a swirl?

“Drops off right there,” calls my advisor. “It’s real deep. Good for catfish, if that’s what you want.”

It’s possible he’s a bit off. But it’s been a very long time since a bit off bothered me much, especially if somebody’s polite and pleasant. And then there’s the maxim my mentally ill students said and proved several thousand times: “Just ’cause I’m crazy doesn’t mean I’m wrong.”

That’s when it hits me:

Meander time. Really, it’s been too long.

The slope’s concreted, roughly, and hard on my bare feet. By the time I’m down, my advisor has removed something from his pants pocket. With great emphasis, he says and repeats a word I almost recognize as the name of a semiprecious stone. “I found it right here, washed out from the mountains. Took it home and ”

He holds up a teardrop-shaped piece of what could be cut glass or the Hope Diamond, for all I know, with a round end the size of quarter and a small, charming flaw near the point.

“That’s beautiful.”

“Yes. A lot of people think so. I found the stone here, took it home and cut facets…”

It takes him a few minutes to describe the process by which he ground and dressed the sixty-something sides. He speaks softly, quickly, and with the obvious conviction that what he says has value — not presumption, but pure sincerity, a sense that knowledge is a gift.

I am interested. I ask questions, despite the urgency that compels me to edge away, because as much I would like to learn more about stones, also tuna and old tortillas . . .

“Was that a fish?” I ask, staring toward the lagoon.

“It might be. That is where I have seen most of them today.”

Today? And other days . . .

No time; I thank him. He nods and, suddenly mindful of my mission, begins to walk away quickly. “Catfish,” he throws over his shoulder. “I believe that’s what they are.”

Saltwater catfish. I’ve caught a few, although never near San Diego — or on the West Coast, that I can remember — unless you count the brackish Delta . . .

I strip line; I’m still stripping when I see a fish boil.

And a fine boil it is.

My first cast is short and rushed. The second covers. Two pulls, and the rod tip takes a bow.

A deep bow; we’re off to the races.

Seconds later, I’ve lost eighty feet of line. I congratulate myself for having tied on fresh tippet and tested the knot. A couple heartbeats after that, I hear my backing knot click through the guides and wonder if I tested it enough. Fast catfish.

I turn to look for my informant, to see his back a hundred yards northwest and upwind.

A moment later, I’m wondering if I can turn this fish before it heads past a train trestle a long way east. No head shakes, no quick jags, just long runs, straight and sustained, that just keep coming.

And going, of course. But the fighting style baffles me. I can’t place the fish among the candidates I hoped to catch this evening, not even the least likely. It’s clearly no perch, larger than any corbina or croaker I’ve ever caught, too fast for a halibut, leopard or angel shark. The sustained runs eliminate bass, whether sand, kelp or calico . . .

White? I caught several monster white bass off a La Jolla beach when Reagan was governor and remember that not ten years ago, a big one took up residence in Oakland’s Lake Merritt. This species does enter inland habitats . . .

The fish interrupts my musings by swimming toward me so fast I can’t possibly reel fast enough to keep up. Naturally, I do that silly “strip-strip-backtrot” for five or ten seconds, startling a gull that had snuck up so close behind me I hear the splat that accompanied its takeoff.

I recover focus twenty feet back from the bank when my fish turns again, now aiming inland, clearly intending to reach Escondido.

It’s back on the reel, which is good. But now it’s way, way out again. I really want to see it, and for once, I’m convinced I will: this hook-up feels solid.

Too solid, I discover, when at last it planes into the stream mouth.

There’s enough light to show me the point fly embedded behind the dorsal of a silver-and-black striped slab. But the sharp disappointment of snagged is derailed by confusion:

A striper? In San Diego?

In a word: no.

I’m still bewildered as I wade out to land whatever it is, which now thrashes wildly, trapped by one of those screwy, two-fly-lasso arrangements. There is the point fly, embedded in its back, a pale pink/orange/brown rabbit leech with a size 8 trailing hook that pins a loop somehow created by my dropper fly, a size 10 red shrimp pattern.

Yes, I have that right. No, I’m not sure it works. Created somehow: the shrimp’s out of sight on the bottom of the head.

Maybe in the mouth, I think, with the kind of hopeful conviction that, even in moment, sounds lame as a worm.

Snagged or fair hooked: it’s still impossible to tell with the fish mostly submerged and struggling. And —

I’ll never know. As my finger traces the leader under a strange, flattened head, the shrimp fly tears free. This release prompts a double, doubly alarming response: a lunge against the snagged hook that rips it loose and, at that instant or instantly after, a gout of blood so copious it looks like the fish’s heart exploded.

Dammit.

All fights end. My catch lies in my hand, unhooked, dying, and for a few more seconds, unidentified. So?

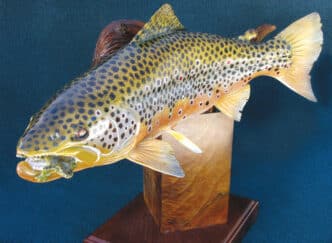

It’s half the size I expected, at or just under two feet, between four and five pounds. The heavily scaled body looks a lot like a striper’s, but the mouth, albeit toothless, is wrong, set low. The jaw edges have odd angles, creating a kind of curved trapezoid joining under the nose. That flat head appears wider than high — and way too small for a body so deep. But the most startling feature: enormous black eyes, almost the size of dimes.

Wait, wait. I’ve seen these. Baked and steaked, on platters in restaurants around the Aegean; also alive, swimming inside the Mykonos harbor. And once I was sure I was watching a big school, in the lagoon behind the Del Mar racetrack . . .

A mullet?

I snagged a bleeding mullet. Now what?

I try not to feel deflated. It helps when I see my advisor. I wave, and he trots across the sand, arms akimbo.

He stops. “You caught that,” he says evenly. “Right here.”

Not much chance of plausible denial.

Instead, “You like fish?” He nods once. “Yes.”

“Well, it’s yours, if you like. I think it’s a mullet. I’ve never eaten one, but I know the kind they catch in the Aegean was about the most expensive item on the menu.”

“That’s quite interesting,” he says seriously, “I happen to have some pineapple.“

What?

“To bake inside.” “Oh. Sure.”

He stares along time. “That is,” he says, pointing at what will be his dinner. “What I thought was a catfish.” He hesitates. “Apparently not.”

Dan’s his name, almost. And aside from a tendency to lead with references not immediately obvious to me, he’s an interesting guy; and a talker.

That’s what he does for the next hour, standing beside me as I cast, encouraged by every question, each of which he takes pains to answer.

Gems, gold, local geology: Dan offers me lessons in a low monotone that cannot disguise lifelong fascinations. (Later I realize how much he looks like the young Dr. Spock, truly not ten degrees shy of a doppleganger.) I notice a slightly formal feel to his speech; he says “yes” more often than “yeah” and often avoids contractions. He also tends to stop in midsentence to gather, sometimes to suck on a Marlboro, but not always. He’ll make eye contact, when I can tear mine away from watching fish, but it strikes me that he’s most comfortable with both of us staring onto the tableau before us. By the time I’ve ventured my third or fourth moment of levity — I can be persistent — he responds with small, surprised smiles. Right or wrong, each suggests that humor isn’t a constant companion.

Over time, the conversation cycles, adding layers. Dan describes a secret place where he pans for gold because he no longer can find work as a machinist. Being unemployed bothers him, and he speaks with quiet regret about the dearth of jobs in his field, the competition from abroad and from new immigrants into the area. He can’t believe the responses of employers offering wages barely above minimum wage and no benefits. “They look at my experience and say ‘No way. When the economy gets better, you’ll leave.’”

“Those conditions, they’re probably right.”

He looks thoughtful. “I suppose so.”

A little gold, a few stones, make ends meet.

I am fishing, by the way. Hard, if not cleverly, in what is now a moonless dark illuminated by the halogen lights of the parking lot above us, also the bright rectangles of a beachside condominium complex a few hundred yards south. The tide rises no higher, but continues to send occasional waves through the thin throat of stream. These press forward into the open lagoon mouth; some widen into low, shell-shaped fans; others, for reasons I can’t fathom, plunge suddenly over the dropoff, spinning vortexes powerful enough to spin kelp fronds into the slack water nearby. Every few minutes, a fish or two — mullet, I’m convinced — swirls in or along current edges, also in a scum line on the facing bank a medium cast away.

I work these areas so often, over fish I know are there, that I now doubt my mullet was ever fair hooked. I’m embarrassed I thought it might be. I change a fly, threading the new one against the sky.

Maybe I had a bump, or bumped something. Maybe not, but . . .

You’ve had those moments, which are longer than that, when you’re throwing a rod and reel that balance so well in your hand that casting feels as easy as petting a cat on your lap or taking the thirtieth swing at batting practice. When the muscles on your strong side, ankle to shoulder to wrist, find a rhythm . . .

That’s what happened in the next hour. I am soothed by the flow of line, also by silver reflections on shifting black water, galaxies of sparks winking from the stream’s broken eddies. The air’s on the cool side of balmy, breakers boom on the beach behind the bridge, and Dan’s drone becomes a murmur as, subjects cycling again, he describes the history and conditions of a mine collapsing not too far away. As to the smorgasbord of thoughts he served to “catfish”: Just a curious mind at work. “I saw them rising up eating things, so decided I should get a better look at them. I found half a can a tuna, threw it out. and they came closer.”

“Fish like this one? Because mullet, I think they’re vegetarians. I thought they were — algae eaters, mostly.”

“I am almost sure just like this one. Then I got some of that seafood salad — it’s imitation, you know. I believe they liked that, but it sank too fast to be sure. That’s when I got the old tortillas. I know they liked them, all right.”

I nod. “ The curious mind,” I say, knowing a little about the subject. “That feeling you’ve got to know.”

“Yes.” His brow furrows. “I believe I have always been like that. Since I was boy, anyway.” Then, unconsciously adding evidence. “Do you know there are crayfish in here? A lot of crayfish. I watch them. And prawns wash in, all sizes. Mostly green, some red.”

Of course, I wonder again where that shrimp fly hooked up.

There’s a mildly awkward moment or two, after Dan and I hike up the bluff from where I first spotted him and he me. Am I sure I don’t want the mullet? “I have that pineapple, but it’s a very nice fish. The biggest I have ever seen caught around here.”

I explain that I’ve disconnected my stove for the remodel I’m doing.

Do I understand that the high tide I saw tonight will repeat tomorrow, bringing the fish back where I found this one?

Yes, although I won’t be able to return until the night after. He falls silent. “But do me a favor,” I add. “If you remember . . . when you clean this fish? I’d like to know what he was eating.”

We shake hands. He turns suddenly, and, to my surprise, heads back down the slope toward the water.

I rise early the next morning and, gifted with a half-hour Internet access via a neighbor’s iffy wireless connection, try to learn something about mullet.

A striped mullet, mine was, no question about that. It looks exactly like several photos. According to Wikipedia, it’s “a mainly diurnal coastal species that often enters estuaries and rivers. The Striped Mullet usually schools over sand or mud bottoms, feeding on zooplankton. The adult fish normally feed on algae in fresh water. The maximum size the Striped Mullet may reach is approximately 120 cm, with a max weight of about 8,000 g.”

Other sites report that this is one of the world’s favorite fin foods — and bait, of course — usually caught in cast or gill nets. It’s even a “Cracker’s Choice” dinner in Southern states. While I don’t find a pineapple recipe, it could be out there, because I do see “Red mullet with hazelnut peach compote and mustard mascarpone.” For a moment, I’m intrigued by a headline, “Mullets Rule the Word,” but this turns out to be an essay about haircuts . . .

All just dandy, but descriptions of striped mullet habits, specifically what they eat, confuse me. One study asserts the young fish are “carnivores . . . preying on microcrustaceans and insect larvae,” but that older, bigger fish are filter feeders, eating “strictly . . . plants and associated plant material that they process in a gizzard.”

U.S. Fish and Wildlife says they’re caught on earthworms, although “oatmeal and chicken laying mash are more popular.”

One way or another, fly fishers around the world catch mullet, though it’s hardly a rage. One Florida captain chums them up with “mash” (chicken laying? Or bourbon?) then dangles a string of five white Woolly Worms beneath a float. Another “creates tiny green flies, the size used on famous trout rivers up North . . . Not Alaska north, but the Madison River in Montana.” A South African angler, who may or may not be fishing the same species, excitedly declares that “I find the Yellow Humpey and the DDD to work in salt and fresh water and to be the most successful!” but Brits from the National Mullet Club — yes, they have one — insist that “gulping” mullet feeding on top “aren’t interested in a baited hook; they’re feeding on something far too small to see.” Several other devotees suggest spreading your bread upon the water, then pitching out deer-hair flies to match.

By the time my computer’s iffy connection cuts out, I’m wondering if, flywise, mullet are today where carp were twenty years ago.

I contemplate this while rolling satin finish “Swiss Coffee” onto walls. It seems a shame that, knowing a little more, I can’t try again tonight.

Instead, I have dinner with my new friend Ed and his wife, neighbors in the mobile home park, hoping to extend a conversation that Al and I had started over dinner at a Chinese restaurant several nights earlier.

That evening, Ed ordered in Mandarin, a language he learned in an intelligence agency many years ago; he also held substantial conversations with several wait staff, who appeared delighted by his fluency. Slight and wiry, he has a subtle sense of humor, wide-ranging interests, a profound and gentle commitment to Christ, and, for the last nineteen years, intractable Parkinson’s Disease.

That disease has taken him places nobody wants to go, the worst of which is isolation.

At the restaurant, he took a pill that helped him master movement for almost two hours; tonight, however . . . tonight, the illness will not let him be still.

He tries. God, how he tries — did I go fishing, he wants to know. I tell him briefly about the mullet, which only excites him more than he can manage.

“I used to fish . . . in Texas,” he says in two bursts. “Loved to, always did. But that was before . . .”

I am calm, and helpless.

“So sorry but . . . tonight . . . I can’t seem to . . .”

“Not to worry, Ed . . .”

“Yes. Not to worry. That’s . . . right. I need . . . to thank God for His gifts. Every . . . day.”

Every damn day — that’s right.

There’s no time the next day to tie tortilla flies; I work too late, so it’s pushing eight in the evening before I head toward Oceanside, well on the way to getting dark before I park.

Dan’s standing right where I was, first time I saw him.

He says hello. The fish was excellent, its meat white and mild.

“Kelp bulbs,” he says suddenly.

I’m getting better at this; it takes just a second or two to recognize the question he’s answering: What was it eating?

“Kelp bulbs? The things that look like brown grapes.”

“Yes. Mostly small ones, some medium-sized. Also, several prawns about . . . ” he opens his fingers half an inch.

My shrimp fly. “What color?”

“They were . . . pretty digested, so I cannot really tell you for sure.”

It’s a shocker, but my fly boxes are bare of kelp bulb patterns, although if I had my lake nymphs, I might have tried a fat amber dragonfly.

Instead, I fish last night’s shrimp and a small olive nymph. When I tire of lobbing the combo, I switch to a Clouser, then a long black rabbit leech, sort of.

For two hours I angle, but tonight I find zip Zen, mostly because the mullet battle so inflamed my elbow, it hurts on every cast. And again, the fish are moving and not taking. But I don’t leave.

Did you know, reader, that the Coast Guard sinks drug ships intercepted at sea? Or did, maybe; it’s been a while since Dan led boarding crews, a part of his history he contemplates with what sounds like disbelief. He’s still not sure why they chose him for this job, but he thinks it was because of his army experience.

Long pause. “And possibly because I shoot pretty well.”

I love understatement properly applied. “Pretty well,” it turns out, means placing in those military sniper contests I sometimes see now on TV.

Ten, ten-thirty, or eleven o’clock, Dan and I discover that we grew up within miles of each other in Arizona; he entered my high school the year after I left. For decades, we’d walked the same deserts, climbed the same mountains, traversed the same canyons, Dan on the slopes looking for stones, me on the rivers below, stalking fish. And we laugh, remembering swims in the canal at 32nd Street — we also knew to share a moment’s silence, remembering how the gates there could, and did, kill kids who dared the gap.

What might be more interesting than that coincidence of place, I realize at some point, is I don’t think either of us is that surprised to have this in common.

I’m still not sure why not.

It was heading toward midnight when we went back up the bluff. We were saying goodbye when Dan told me that, while he hadn’t fished in years, he was thinking about bringing spinning gear with him, trying a Roostertail spinner, and, given the Internet information I’d relayed to him — maybe even break out an old fly rod he’d never learned to use.

I hesitated before answering.

The lagoon changed a lot with tides, he continued. Usually the stream didn’t run at all, but disappeared into the sand; sometimes he dug the channel himself. So if I knew when I was coming back, he’d try to make sure . . .

It was awkward. I told him I’d try, at least once, though I couldn’t be sure when; my family was coming down to visit, see the remodel, then I’d put the place on the market and return to home a long way away, taking my son Max on the “road trip” he’d begged for.

He considered this in silence. A moment later, he extended his hand; we shook.

“Well,” he said. “Maybe.”

Again, he walked down toward the stream. I watched him until he reached it, turned, and threw me one long wave.

I almost called him back. What harm to get a phone number or e-mail address? But no, lacking those, I’d do as I’d promised: try.

And I did. But it was four days later, with Max, armed with a cheap spinning outfit Shimano should be ashamed to put its name on, also a jar of kelp bulbs we’d collected from the beach. I’d wanted to bring Ed, even though his tremors filled Max with such an agony of empathy he could hardly speak in his presence, but that didn’t work out.

Different tides. The stream disappeared into a new mound of sand that looked piled up by an earthmover. No mullet where they’d been.

No Dan.

“Is this where you met him?” Max asked, “the Coast Guard guy?”

“Yeah. Maybe he’ll come by later.” “Oh. How long we going to stay?”

Wood lice. Floating maggot flies fished in the surface film. Idothea and a pattern tied as a “black seaweed spider.” Fly fishers — a few — do indeed pursue mullet, in Florida and other Gulf states, in

England and Scotland, South Africa, maybe Israel and Japan. Thin-lipped, thick-lipped, gray, striped: YouTube has a dozen videos on the subject, a couple showing battles that ought to impress. In case you didn’t catch it the first time, 120 centimeters comes in a little under four feet. (Note that most sites put the striped varieties’ upper limit at around 18 inches — I’m telling you that’s wrong — but the variety I saw around the Med reached a full meter at least.)

The new carp? (And yes, I grin as I write that.) I wouldn’t be shocked. They might even catch on more quickly, starting out with a less trashy rep. To those of you who like listening to Ken Hanley as much as I do, the next time you see him, say “Jump on this, Ken,” or pick his brains if he already has. . .

If you appreciate possibilities, live a little beyond the pale. If you’re open to a meander once in a while.

I’m talking about fish, too.

I kick myself about Dan. I kick harder for something else that happened.

Two days after we missed him, Max and I were ready to leave. I left out the crummy Shimano outfit to pack someplace handy for the waters that will tempt us off I-5.

“No,” said Max firmly. “ We’re not taking that.”

“We’re not.”

He shook his head. “That’s for Ed. You said he wanted to go fishing, so we should leave that for him so he can. If he gets better, or something.”

“You think so.” “Yes.”

We did, late that night, tucking it under the canopy of his patio.

Five days later — somewhere late at night, driving between Dunsmuir and Weed — it struck me how dim I’d been. How did I miss this?

Like minds, filled with special curiosity, a kind of patience and sincerity. Christ, even faintly similar hesitations in speech.

How could I miss it?

Dan. Ed.

A connection made in Heaven — could be.

Could have been …

“Dad?”

“What?”

“Is something wrong?”

I explain.

Max tries to ease my angst — a new role for him. Then he’s quiet a long time.