Bats on dries? It’s something to think about. Now that fly fishing for golden retrievers is such a rage, I’ve no room to double haul at the dog park. . . .You have to wonder how California Fly Fisher magazine stays so cutting edge.

— Fly-fishing commentator, quoted off the record

This year’s angling was so awful that my dog days were the best by far. As usual, a big problem was time, stolen by the usual suspects, plus those specific to late-spawning middle-aged fishers challenged by menopause — our own or somebody else’s; also adolescent crises, and the serious illnesses of parents. In 2011, these demands proved so consuming that I rarely landed on the water earlier than an hour or two before dark thirty. They also guaranteed that when I was finally afloat or wading, my cell phone struck more often and urgently than fish.

I’d blame time more bitterly, except so many of the season’s failures were mine. Dusk is a fine time to fish, after all, spring through fall; but even when arriving late I found myself poorly prepared, geared for hatches that rarely appeared and were weak if they did. Worse yet, I failed to figure out what was happening instead. I cast with the élan of an eland — a large antelope lacking opposable thumbs — and tied knots with hands that felt like hooves. “What am I, knitting a sweater?” And yet, I found myself all thumbs when reacting to chances I had to hook up.

Naturally, I began to suspect I had lost my “touch.” Later, I wondered if “chops” wasn’t the better word. Naturally, I tried to dose ennui with better memories, inflating these when necessary. When nostalgia failed, I fell back on that “count your blessings” stew grown-ups cook up as comfort food. But the recipe lacked important ingredients, so too often left me with a thin gruel salted by bitter doses of “C’est la vie.”

So it went, May into August, then into September. By autumn, it seemed like I should have learned something — managed some epiphany or insight that would grant a sage perspective to blunt, a little, the sharp edges, tragedies, and failures, fishing or otherwise.

One would think. And if inspiration did not arrive — then perhaps it was time to push a little, extract inspiration from the ordinary, maybe torture “Eureka!” from a pedestrian or pedestrian moment.

I remember arriving at the launch an hour or two earlier than usual, then wasting too much time messing about with a boat, not happily; also that I was further delayed rerigging leaders and tippets gone wrong during my last rushed trip. I remember that when I was finally offshore, one oar seemed suddenly to warp in my hand — a real and annoying bend and twist that certainly did not result from a heroic pull. I remember that I drifted quietly, watching for rises nearby. And then, seeing none, that I expanded my search farther out and up, at least, scanning the lake’s pale horizons for the loveliest of fish-tale informants I’ve come to trust.

Swallows. Slow as I’d been to set up, the sun still hung eight inches above a western hill. That meant this was still Swallow Time, first step in the satisfying evening sequence I’ve enjoyed on this lake for years.

I write “evenings” mostly because that’s when I’m in the best position to see swallows. My local birds may hunt at any time of day, because they also depend on hatches, mating swarms, the laying of eggs, spinner falls, and, sometimes, events such as the autumn migrations of flying termites, which small flocks of swallows will attack high in the air, creating a light rain of amber body parts, odd bits of carapace and pieces of wings. But during the warmer months, evenings bring swallows out in greater numbers, when they concentrate in air spaces above waters where bugs emerge or seams where winds blow cripples.

I try to reach these spots, knowing that the swallows — shy birds — won’t stay if I do (though they sometimes return). Even at a distance, however, they’re swift and graceful, such pleasing creatures to watch. I even like the word that authors often use to describe the shape of their wings: “chevrons.” As to their talents, say what you like about the vision of raptors, I can’t imagine eyes tuned more brilliantly, able to track an erratic caddis through swoops and rolls, arcs and glides, and the single-wing dips that swallows use as they turn to fly vertically.

In short, watching swallows is one of the few things that will make me pause full minutes while fishing. I admire them, like the feel of that admiration, and often wonder if swallows only doing their jobs still might find flying as exhilarating as it looks. That’s silly, of course — as silly as imagining that my retriever enjoys fielding balls as much as I did turning plays at shortstop. “Anthropomorphize” has been a term of disdain since I was a teenager, employed to dismiss interpretations of animal behavior that only dim folks entertain. Even so . . . while I appreciate the effort to preserve an objective, scientific perspective, this idea has seemed like arrogant crap to me for so long — an anthrocentric assumption that only creatures sentient enough to describe emotions to us can have them — that I ponder the pleasure of swallows whenever I want to.

But not this evening. Not a single swallow worked the surface for as far as I could see — a bad sign if I hoped to find fish feeding on the surface. But I remember hoping, if faintly and without conviction, that a late hatch might still bring up fish.

And bats. Also bats.

Maybe it happens more often, or more memorably, in years when the fishing’s lousy: your attention wanders, you see more, and — when it comes to bats, which I also like to watch — you notice absences more acutely. Bats have been scarce this year and I miss them: if swallows are aerial dancers — imagine some lovely ice skater released from gravity — then bats are acrobats, agile beyond belief. Beyond that . . . hunting bats are well and truly obsessed, not shy at all. While their echolocation is amazing, it ain’t perfect, so bats make mistakes. I find this interesting, also familiar and, well, endearing. (Usually. A bat was the very first thing I took on a fly rod — actually, it struck my rod while chasing my fly and fell mortally injured, causing my boss at the little fishing camp to accuse me of “wing shooting with a fly rod.”)

Having lots of bats around means I get to watch lots of great flying, also to witness lots of mistakes. When the right hatches happen on this lake, bats take my flies more often than trout and bass combined, some nights in a ratio of five to one. In my early days I found this flattering, if baffling. It got annoying pretty soon —I’ve never fished a water with so many bats — and remained that way until I learned the game. My observations, and the rules by which I play:

A bat (many bats) will bang a big dry fly on the water, often two or three times. Don’t do a thing. Wait until you’re sure it’s done investigating, then tighten up slack. From what I can tell, once a bat’s learned This ain’t it, it won’t bother you again.

More aggressive bats will grab the fly and lift it into the air, sometimes two or three feet. Again, don’t do a thing. It will determine the faux nature by feel, or maybe when it feels the leader tension, and drop the fly without — in my experience — ever hooking itself. Your fly is simply repositioned, so tighten up.

If you’re inclined to make vertical casts, don’t. Bats chasing bugs in the air seem oblivious to anything else. This includes fly lines — tight loops get them into trouble — also your rod (à la “wing shooting”). Be especially careful when you’re reeling in a fly to check or change it. That last moment — when you’ve stopped stripping and are letting the fly drift to your hand — can lead to the kind of lap dance that’s just plain awkward in a float tube or boat.

So?

So maybe there will be bats,I remember thinking. But until a hatch brought them out, and the fish, I might as well troll a sinking line over to the sill that divides lake basins a quarter mile away, there to work deep along a point and drop-off until the sky turned darker.

I was preparing for that when my cell phone played a startling tune programmed by an adolescent, without permission, the day before. . . .

I remember that I flinched at the sound, ground enamel off my molars, and almost didn’t answer; that the phone nearly slipped from my hand when I checked the caller ID, and did. I remember my wife’s small cries and sobs.

Everything changes:

Death watches end only one way. But even after Alzheimer’s empties a mind over years, even after the body’s exhausted at last, one way or another, and so begins a collapse marked by aching moments and dry gasps . . . still, for the living, the preparation for the end is not always complete. In that case “for the best” is a small sort of solace, expressing relief born of an accepted despair. You might thank God for release, but there’s no “Hallelujah” in your prayer.

Drifting. I ship the oars. My wife’s a long way away, standing by herself outside a hospice, staring into a desert’s red sunset. I’m in a small boat surrounded by greens and grays. We murmur to each other, sounds more than words, the smooth shapes of sympathy and sorrow. My wife is sure there had been a moment when her mother, sentience stolen so long ago, said goodbye.

God knows that was important. Miraculous, in effect. She still felt the embrace of that farewell, and would forever. . . and now had miles to go before she slept. No, there was no help I could offer, nobody I must tell or comfort,

Nothing to do but drift. So I do, with nothing rising around me but memories of Margaret, who’d never been anything but kind to me. And then . . . for some reason . . . it seemed like the time to row. No, important to row, somehow So I did for a pretty fair distance, dragging sine waves across a small bay of riffled glass. When evening surrendered to dusk, I began to row back.

I saw the bats first. A few, darting well above the water, jagged shapes flying jagged paths.

Too late, I remember thinking. But a minute later, one big mayfly popped up, still kicking from its shuck.

It seemed so surprising. So surprising, in fact, that I waited a full minute to ship my oars again, then put a hand on my dryfly rod.

Another Hexagenia popped a hundred feet away, visible to me because its struggles marred a sheet of silvered black.

I had no idea this second emerger would be the last of the night. So I cast, more toward the first Hex, just as a bat tore it off the surface.

Instantly, two tiny furies fell on my fly. They skirmished for a fraction of a second before the victor lifted it so high off the water — three feet at least — that I felt my line tense, even as the bat’s wings flared wide. When released, the fly fell only a moment before the second bat snatched it from the air — followed by a third — even as a fourth and fifth whirled about and —

Jesus.

I tried not to react. To play by the rules. When these were done — but more bats kept coming. Eight? Ten?

Impossible to tell, but now it seemed to me a small maelstrom. Also, that the bats that had grabbed and dropped the fly remained excited enough to stay in the fray.

They’re crazy, I thought. At the same moment I recalled a quick conversation with a neighbor, a woman who fears bats beyond reason. She’s told me, “It’s a strange year for bats, they say. There are fewer than ever, showing up in strange places.”

Crazy? Starving, maybe.

Maybe. For sure, however, things were not getting better, so when next my fly fell to the surface I stripped hard, three times, trying to sink it. That worked for seconds, because I tie this pattern with foam. Worse yet — when it popped up again, the bats seemed convinced it was a new bug.

Not good. This hadn’t been a long cast to begin with. At thirty feet away, I was a little too close. Near enough that I stripped in again, furiously, hoping to keep the fly submerged. Then I stopped, on instinct, more or less, as I felt a bat flip at my ear: just the whip of wind from its wings, I’m sure, but startling, more so because at the same time another bat — I think another — slapped my line not five feet out from my rod.

So I stopped. Hesitated, might be the best way to put it. And in that odd pause found time to ask myself, calmly, if I was afraid.

The honest answer was no. Surprised, sure. Alarmed, OK. But afraid didn’t fit, and when I wondered Why not? answered with a Why should I be? followed by I’m not, so it doesn’t matter.

By then, things had changed. I tie this fly with a body of foam, but its tall wings are deer hair and were now soaked through. It did not surface as I thrust my rod deep underwater and slowly stripped until I felt the hook hit the tip top.

There were still bats, but they circled high above me, slipping in and out of a dark that showed stars.

I sat, waiting. You can often feel an epiphany coming, or I can mine. A certain stillness surrounds your mind, even as you think very clearly.

I had that feeling. What I thought was this:

It made sense that bats would be hungry, in a year when I could not find hatches.

Margaret, my mother-in-law, who had never been anything but kind to me, was dead forever.

Her daughter, my wife, was in mourning; our teenagers were at home, safe, but probably squabbling.

I waited a while longer, to see if there was more — some lesson of consequence that might justify, I don’t know, confronting the end of a life, experiencing a maelstrom . . . nothing.

I found nothing. I realized I was cold, and that I could smell winter in the wet air rising from the water, a taste like steel on the back of my tongue. And then I was rowing again with one bent oar, pulling through that quiet and private chill that touches you, nights on the water, even on a lake you know well, as you realize you are an outlier of sorts, a trespasser, if not a thief, and that this can be true in other places and times of your life.

Postscript

“There’s always next year,” says a pundit or two, which is true until it isn’t. But halfway through this Meander — actually, soon after the early whining — I found myself outraged enough to take a whole day fishing. To fight for the time, if that’s what it took.

I did fight and lost all morning. The tide turned around noon, so by one o’clock and change I was on the road, hoping any ice that edged the river had melted by now and wouldn’t freeze again before four, if I was lucky, leaving almost three hours.

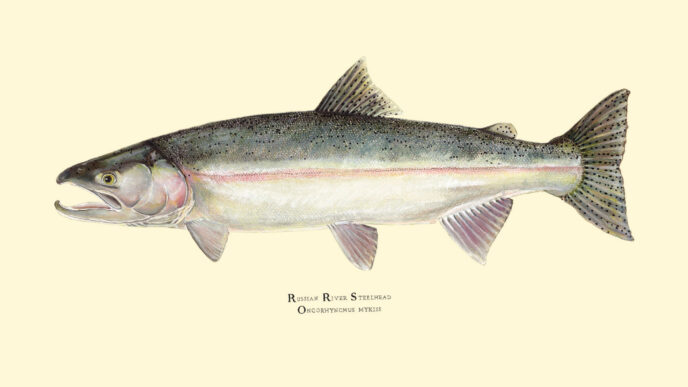

I had the river to myself. I wanted to believe this was because I busted brush walking in, but I knew the better explanation: the last salmon run was done, and neither steelhead run had arrived.

Given these hard facts, it was difficult to decide just which of these species I hooked my first cast into a fast, shallow run, a fish that fought me down into the chute below, back, then upstream into a tailout of a pool above, across again, and do-si-do.

Neither species, it turned out. This was a trout. (Definitely a trout.) I didn’t measure her, so I can say twenty-six inches and you may believe twenty-two-plus. (No, really.) I fought and lost one more that size before ice became a bother. I answered only three of the seven cell phone calls that sifted into the canyon (God, I wish I were kidding), while ignoring every single text. I had no epiphany. But I felt pretty good. That was enough, and there was even a little icing: 2011 had a fish to remember.

And more. I cannot forget the bats, I’ve found — their tiny maelstrom, the wings or whipping wind that brushed my ear, my awe-touched alarm . . . . And I cannot forget the taste of winter, steel on tongue, nor the feel of an outlier’s alienation, murmurs of sorrow. . . .

It makes no sense to me that I seem to find a small mercy in these, which some years may be the best there is, and for which I should be grateful.