I’ve never been any good at tying flies. I envy those who have the patience and dexterity to do it. I once bought a vise to give it a go, and when I showed a friend my attempt at an Elk Hair Caddis, he said, “Lucky you didn’t decide to be a surgeon.” That was mean but accurate. I gave up after that and became the kind of customer fly shops depend on to increase their profits. It’s ironic, really, that I own a collection of vintage flies that should be in the American Museum of Fly Fishing.

They arrived in a small plastic fly box, a gift from Nick Lyons, the renowned publisher and fly fishing writer. Some years ago, Nick invited me to write a book for his press, and I was delighted. I knew the book would be beautifully produced—Nick’s titles never look slipshod—but the flies came as a surprise when I finished Crazy for Rivers. Inside were eight flies tied by masters of the craft—Green Drakes by Dick Talleur and Tatsuhiro Saido; 3 Soft Hackles by Lew Terwilliger; an old Yorkshire wet fly; and Gray Fox Variants by Len Wright and Art Flick.

Flick’s name jumped out at me. I recalled a time when every serious fly fisher carried his Streamside Guide to Naturals and Their Imitations in a vest pocket. It was designed to fit there, too, a mere four by six inches and only 114 pages. Each chapter focused on a species of mayfly, starting with the Quill Gordon and ending with the Green Drake. Although Flick’s home water was Schoharie Creek in the Catskills, his research, a three-year project, produced results on any river that held trout. He offered life histories of the mayflies, hatch charts, and lessons from his own experience.

The guide made Flick famous, but he didn’t much like it. He’d never have bothered with the book if a close friend hadn’t pestered him. He was content in West Kill, where he ran a tavern while his wife, Lita, cooked up meals for his pals. He was active in the Catskill Mountain chapter of Trout Unlimited, one of the first anglers to fight for catch-and-release fishing. But his Streamside Guide received such praise and sold so well, Flick was constantly fending off fans wanting advice or hoping to buy a fly Flick had tied.

John Voelker of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula was one such fan. He, too, was an author under the pen name Robert Traver, which he’d adopted so as not to compromise his position as a Michigan Supreme Court judge. His Trout Madness was a smash hit with anglers, who loved Voelker’s warm, witty stories of pursuing brook trout in the wilds of the U.P. Voelker had also published a best-selling novel, Anatomy of a Murder, a courtroom drama Otto Preminger turned into box office gold.

He’d never written to an author before, he confessed in his letter to Flick, but no one had ever explained the nymph-dun-spinner cycle so clearly. He liked the guide’s simplicity and asked Flick for the name of a Catskill tyer who could duplicate the patterns for him. The name Voelker meant nothing to Flick. He was fed up with these intrusions and suggested Voelker try Harry Darbee of Livingston Manor, although Darbee was so busy, Flick doubted “he would even answer your letter.”

Not long after, Voelker sent Flick a thank-you note and a copy of Trout Madness. Flick was embarrassed when he opened the parcel. He hadn’t connected Voelker with Robert Traver. He had a “terribly red face,” he confided in his reply, enclosing 10 of his flies by way of an apology. He followed up with a phone call on Christmas Eve. Voelker was already in a bourbon-enhanced celebratory mood and answered, “Michigan’s mightiest piscator.” That got a laugh out of Flick.

Voelker sensed a kindred spirit. He invited Flick to visit and fish, but Flick hesitated. He’d sunk roots in the Catskills and must’ve known the trip involved a friendly challenge. That’s always the case when fly fishers tackle a stream together, but his curiosity and Voelker’s charm finally moved him to pack up and drive to Michigan by way of Canada, arriving in late June 1962 ready to wet a line.

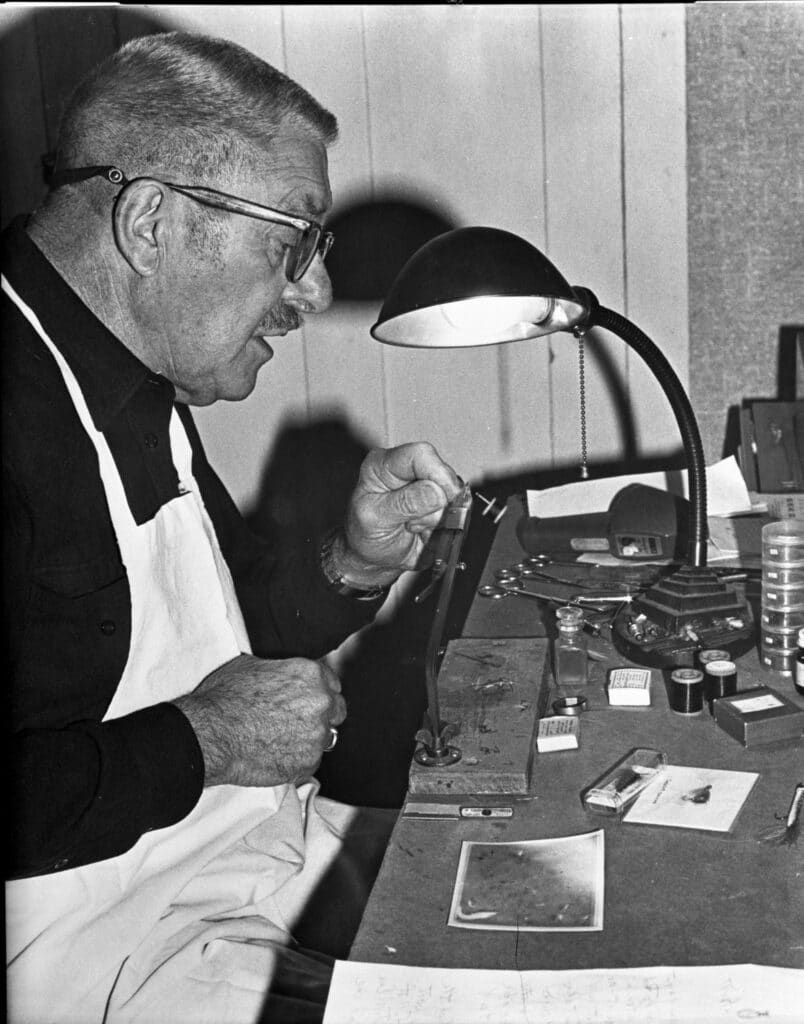

Voelker described his guest as a tall, tanned, crewcut man with a boyish manner in his story, “A Flick of a Favorite Fly.” If Flick had the disadvantage of fishing the U.P. for the first time, Voelker’s challenge was to deliver some results on the home waters he’d bragged about. For all his skill as a tyer, Flick stuck to his usual game plan and used just six flies. He believed presentation mattered more than matching the hatch.

“If you want to make sure the fishing will turn lousy, just dare to invite a fellow angler from far away; the farther away, the lousier,” Voelker wrote later, sure that he’d been cursed. He and Flick spent six days fishing rivers, streams, ponds, and beaver dams without much luck. According to Voelker’s notes, he caught eight brook trout, mostly fryers—small enough for a frying pan—while Flick caught 10, only one a fryer.

Voelker was about to give up and tell Flick, “You shoulda been here next week,” borrowing a line from a local guide. Instead, he decided on a last shot and led Flick to the old beaver dam on Frenchman’s Pond, “the very hottest spot in the hottest place I knew.” Flick tied on a new fly and began casting. Voelker couldn’t believe the size of the fly, much larger than the small ones he’d been suggesting. It whooshed by like a small bird.

It was Flick’s favorite, a Gray Fox Variant with a tail but no wings and long hackles. (Other fly tyers and anglers define variant differently.) He often used it as an attractor when nothing was hatching. Voelker watched him lay out a perfect cast. “There was a sudden flash as if a shaft of lightning as a great dripping creature rose and in one savage roll engulfed Art’s fly,” he wrote. Flick set the hook, but only a few seconds later, they heard a telltale ping signalling the giant fish had broken free.

Flick wasn’t the first to put his faith in variants. William Baigent, an Englishman, originated the trend in the 19th century. He proceeded by trial and error, starting with different versions of a fly, tossing out those that failed, and modifying the ones that caught trout. Flick’s Gray Fox Variant could be taken as a distant cousin of the Green Drake, but he couldn’t explain why it worked so well. “Something about variants seems to excite the trout,” he said, “and often they will come up and smash them when they do not want [to eat] them.”

Though Flick gave Voelker a batch of Gray Fox Variants to try, the trout refused to play ball, and Flick headed home. Whether they kept in touch is a mystery to me, but I do know they both spoke of having learned something new from the other fellow. As for my own Gray Fox Variant, it still rests quietly in its plastic case. I’ve been tempted to use it once or twice, but I have a feeling the ghost of Art Flick might rise up and take offense.