Many birds fly south in the winter, and that includes Steven Bird, an author (see “Lonesome Coast” in this issue), guide, lodge owner, and fly designer who spends the cold months on California’s Central Coast, but who lives and fishes on the American Reach of the upper Columbia River in Washington, close to the Canadian border. Steve Bird has written about that fishery in Upper Columbia Fly Fisher: Notes, Stories, and Secrets from the Shining Reach (Frank Amato Publications, 2010) and has published short stories, but his writing about his stunning home water — and about his fly designs, as well as the approach to fly fishing that lies behind them — also is to be found on a series of blogs: Soft~Hackle Journal (soft-hacklejournal.blogspot.com), Upper Columbia Fly Fisher (http://columbiatrout.blogspot.com), and Upper Columbia Trout blogspot.com). Steve is an innovative traditionalist who exemplifies a kind of rooted nomadic lifestyle increasingly characteristic of fly fishers in the age of the Internet. And he designs really interesting flies.

Bud: I was trying to plot the coordinates of your life, and I came up with a series of dots: east-central Massachusetts, Southern California, waaay up in northeastern Washington, near the Canadian border, and the California coast around Big Sur. Could you connect the dots? And what role did fly fishing play in the way these dots got connected?

Steve: Once, while fishing for albacore aboard a California open-party sport boat, I overheard a conversation between two of my fellow anglers that gave me pause for thought concerning my “bio.” One of the guys was Greg Jacobson, a hard-core regular, whom I knew to be a successful criminal attorney. The other guy, who looked well heeled, asked Greg what he “does.” And Greg, casual, without skipping a beat, replied: “I’m a fish bum,” then turned and walked away. And that made an impression on me. I’m thinking: “Now that is ultimate cool. The man does not define himself by his credentials or what he does to make money, but rather, he defines himself by what he loves and is most interested in.” I’ll lay down this bit about myself in that light. I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, and began life in Shrewsbury, on the shore of Lake Quinsigamon. I started handlining bluegills from the family dock at the age of three and received my first rod at the age of four, one of my grandfather’s old bamboo fly rods. I had good mentors. My dad fished. My uncle George, who lived next door at the lake, was a charter boat captain. My dad grew up in Shrewsbury, close friends with the Woolner family and the great outdoor writer Frank Woolner. My dad and Frank and their friend Sid Dickinson, a Micmac Indian who used to make his own six-foot fly rods for fishing the small New England brooks, used to set their tilts on the frozen cove behind our house and pass a flask around while I watched for a flag to spring up, hanging on every word they said. And of course, much that they said was pure bull meant to fertilize an already overactive imagination. They planted seeds.

The greatest influence on my fishing life was my mom’s father, George Brunell, a dyed-in-the-wool Down East hard-core angler who fished a lot and always took me with him. In the spring, before the trout went deep, we’d troll the lake with streamer flies, old-time patterns such as the Gray Ghost, Silver Doctor, or Red Ibis, trailed 70 feet behind my grandfather’s ancient Old Town canoe, the bamboo rods arcing deep to the grips and rattling against the varnished rails of the boat whenever a trout slammed the streamer.

I was with my grandfather when I caught my first trout on a dry fly, from the Assebet River, in central Massachusetts. I used to count the days leading up to our annual trip to Missisquoi Bay, in Vermont, at the northern end of Lake Champlain, where we stayed at a Victorian fishing lodge that featured a row of rocking chairs — there must have been fifty of them – lining the gingerbread porch running the length of the building. And — my favorite — a giant mounted northern pike hanging in the dark, wood-paneled foyer, just inside the transomed entry. The place was staffed with a troupe of frisky French Canadian maids, who were my grandfather’s favorites. At the time of my youth, the old lodge was running down, full of sporting ghosts from a past century. It seemed imbued with the compelling mystique of the mythic angling glories of a less cynical, more genteel and grandly naive era.

We’d troll the bay for pike using big Daredevils or cast the vast backcountry lily-pad beds using weedless spoons tipped with pork-rind frogs. I learned to cast with my grandfather’s round baitcasters, lined with Dacron, long before I owned my first spinning reel with mono. And I still enjoy plugging with a baitcaster. My grandfather was a fly fisher, yet he was also a fun-loving pragmatist holding to a broad definition of what “sporting” means, and it was not beyond him to fish both a bobberand-worm combination and a dry fly on the same outing, as he interpreted the dictates of the situation.

My father was a tool-and-die maker by trade. Southern California was booming with the aerospace industry in the early 1960s, and that’s where the money was, so when I was in the fifth grade, he packed up the family and moved us to Glendora, in the foothills of the San Gabriel range. For a kid from the woods and ponds of rural Massachusetts, the move was fairly traumatic, initially. But those who must fish find a way to water. It didn’t take me long to find Puddingstone Reservoir in San Dimas and the San Gabriel River in the mountains behind our home, and I became a frequenter of both places. Also, luckily, my mother was a beach nut and took my brother and sister and me almost daily in the summer down to Santa Monica, Newport, or Huntington Beach, where I would spend the day fishing from the piers.

But it was the San Gabriel River, which was a lovely stream with a sweet native-trout fishery in its upper reaches, that held a particular attraction to me. It was there that I found the solitude, the escape from the southern coastal plain’s smog and clamorous urban sprawl, that I craved. I became a regular, armed with the 9-foot 6-weight Heddon Pal glass rod my grandfather had given me just before we left Massachusetts. As a regular, I met other regulars, talented anglers, some native Californians and others transplants like me, fly fishers from Michigan, Colorado, and the Missouri Ozarks, also Californians of Japanese ancestry, intensely avid and innovative anglers whose Zen-clean, clutter-free approaches to presentation, whether bait or fly, impressed and influenced me.

Those were less fearful times. Men in those days would befriend and mentor a likely kid they met a-stream, and those good men I met while fishing the San Gabriel, all of them gone now, generously shared their knowledge with me. They were my examples and heroes, and I wanted to be like them.

By the time I finished high school, I’d decided I didn’t want to live in Southern California. I loaded my backpack, strapped the Heddon Pal to the frame, and took off, hitchhiking toward Massachusetts, where I’d planned to attend college, yet with no plan as to what I was going to study. On the way, one of my rides dropped me off at a desolate ramp near Lyman, Wyoming, where a good-sized creek passed under the road, the Blacks Fork, which flows to the Green River. I looked down from the bridge and saw what I thought might be a group of large suckers lying in the current. It was late summer, and the high plains were rattling with big grasshoppers. While I stood looking down at the water, a hopper came floating down, and as it approached the “suckers,” one of them rose and inhaled it, leaving the most powerful rise ring I had ever seen. I had a couple of Joe’s Hoppers in my fly box. . . .

I ended up camping under the bridge for four days while I explored the creek up and down, catching huge browns and rainbows from nearly every run, trout such as I’d seen only in magazine pictures. I didn’t encounter another soul. It was hard to leave that place. And I think it may have been there in that big country, under the long Wyoming sky, that the West put its brand on me.

I lived with my grandfather, in Shrewsbury, by the lake, while I attended school, and he and I resumed fishing again as if we’d never left off. Summers, I worked as deckhand aboard my uncle George’s charter boat, Haddock, a sleek, 35-foot Nova Scotia–built lobsterman converted for sport, berthed at the mouth of the Merrimac River, at Newburyport. We fished for stripers around the mouth of the river and for bottom fish, cod, and haddock up at the Isle of Shoals, sometimes offshore for giant pollock. Yet I was restless in the East. In the summer of my second year there, my grandfather passed away, and I suddenly felt like my main connection to the region had been severed. All of my grandparents had passed. My mom and dad, brother and sister, were out West.

I returned to California and within a month of arriving there embarked on a road trip with a high school friend, to Albany, Oregon, to visit some friends who had migrated there. While there, I met the love of my life, Doris Pease, and fell in love with the Northwest. Doris was born in Toledo, Oregon, and like my father, hers was a machinist, and her family had migrated to Southern California at the same time mine did. And like me, she had always held the desire to get back north. (I named the Northern Girl streamer after Doris.)

Doris and I married the following year and rented a shack outside of Eugene, Oregon, where the graceful and talented Doris barely escaped becoming one of Ted Bundy’s victims, by grace and her own reliable intuition. Due to word-length constraints I’ll hold back that account here, though it is included in Far West, a collection of short stories for which I’d like to find a home.

We’d only been in Oregon a few months when Ted Murray, a high school buddy from Glendora, called from northeastern Washington, where he was contracted to build a house in the Aladdin Valley, not far from where the Columbia enters the United States from Canada. He needed some help, and I needed a job, so I went up, leaving Doris and our recently born son, Gabriel, in Oregon.

That was 1974, and that country in the extreme northeastern corner of Washington still possessed the aura of authentic wildness. There was no television reception. A lot of people there (and there really weren’t a lot of people there) had outdoor plumbing — outhouses. There were cabins with snowshoes that weren’t ornaments hanging next to front doors. Reading and storytelling were major entertainments. Everybody read everything and dog-eared books were passed around the neighborhood and often discussed. I read everything Louis L’amour ever published and was introduced to some remarkable books, such as Andrew Garcia’s Tough Trip Through Paradise, a local favorite. There was an amazing little trout stream running through the property where we built the house. And there was enough trout water within a 60-mile radius to keep a guy busy for a lifetime.

I went and fetched Doris from Oregon, and we found an old log cabin on 20 acres, beyond the power lines, situated in a meadow, on a bluff above the confluence of the Pend Oreille and Columbia rivers, right next to the border with Canada, a place we were able to rent in exchange for caretaking. We fixed it up, added fencing, a garden, outbuildings, critters, and built it into a snug, neat homestead. Doris became an expert at cooking on the ancient Warm Morning wood-burning range, and, to this day, I’ve never eaten finer meals than the ones that came off that old stove.

When the Aladdin house was finished, I needed a job, so I hooked up with a band of locals, transplants from California, who were working as tree planters and cedar salvagers. That work led to an interest in silvaculture, which I pursued, eventually starting my own company, Intermountain Reforestation, performing precommercial thinning and tree-planting contracts all over the Intermountain West, from New Mexico to Washington and down the coast to Northern California. That work brought me to many of the great rivers and a lot of unheralded streams that proved even better than the greats. I saw a lot of spectacular country and experienced a lot of incredible fishing, yet to my mind, none of it could surpass the forested passage of the Columbia River and its fish hidden between Lake Roosevelt and the border.

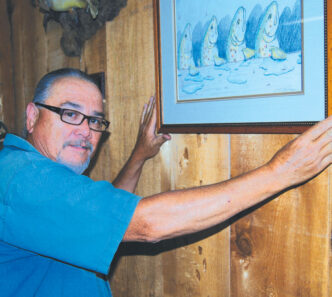

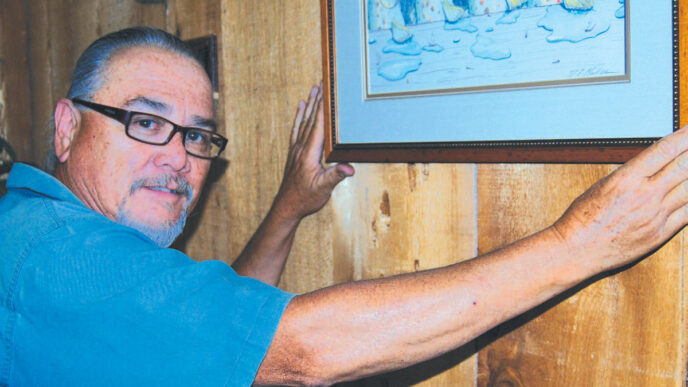

Bud: You guide and run an angler’s lodge, Fat Camp, on the American Reach of the Columbia. The Mighty Columbia is seven miles wide at the mouth, and up near the Canadian border, it’s still a honking big river. What is a trout fishery like in a river that makes parts of the lower Sacramento look like a Hat Creek?

Steve: The American Reach, that segment of river flowing between Lake Roosevelt and the U.S.-Canada border, is one-quarter to one-half mile wide, an average of 60 feet deep, with an average surface speed of six knots and a high-water flow of 200,000 cubic feet per second. It is a river of superlatives — the largest tailwater native trout fishery in the world. I read an account of a guy who drove all the way over from Seattle to fish, pulled off on a turnout to have a look at the reach, then turned around and drove home without ever getting out of his truck, he was so intimidated by its size.

But you can break it down into water that you can fish with a fly rod. Trout concentrate in the seams of the many point eddies lining the river’s banks. The bottom is heavily cobbled with skull-sized stones that wedge and eat your bead heads. You want a fly tickling over the bottom, rather than jigging through it. The river begs for a downstream approach, and the trout oblige, showing a decided penchant for hitting soft-hackle patterns swung, lifted, and dangled. Wild Columbia redbands average 19 inches, but every year, we catch some fish in the 10-pound class. My personal best was a 17-pounder, which I took on a red-and-white Daredevil back in the early 1970s, and fairly recently a 25-pound red band was taken on gear. It is water custom-made for twohanded trout rods, and with the presentations two-handed tackle makes possible, I wouldn’t be surprised to see somebody break the 20-pound mark, on the fly, in the near future.

Bud: What are the advantages of twohanded rods for trout, what are the disadvantages, and how do these balance out in a positive way?

Steve: Technically, the only thing that defines a “two-handed rod” is the addition of a rear grip, and in that, I see no real disadvantage, unless a few grains of weight are a factor. I have 8-foot and 9-foot singlehanded rods that I’ve modified with the addition of rear grips, to no disadvantage in their use as single-hand rods, yet gaining the advantage of being able to perform really good roll casts in close quarters.

But home modifications aside, considering the rods available on the market, I would still give the nod to single-handed rods for dry-fly fishing where a lot of false casting is necessary to dry the fly between presentations. However, on big water such as the lower Sacramento, during a spotted sedge emergence, an 11-foot switch rod rated for a 6-weight or 7-weight AFTMA line might be a deadly effective tool, set up with a tandem of soft-hackle emergers, particularly if it is a pot-shooting situation such as happens on the American Reach, where you are anticipating roving gangs of rising fish and there is the need to get the fly on them quickly while they are up and in the mood — the two-hander delivers without time wasted in false casting, and it delivers over long distances.

Bud: I know you’re a fan of tippet rings, which Ralph Cutter also has lauded in these pages. Compared with just a simple loop-to-loop connection, what makes them something that anglers should embrace?

Steve: The ring is actually simpler than the loop-to-loop connection. Cleaner. If you tend to throw really tight loops, there is less chance that your double-nymph rig will snag on the connection. The ring is ideal for high-stick nymphing, too, because the dropper fly is attached to a short tippet fastened to the ring, eliminating the need for a hook-snagging dropper loop. In the event of a break-off or wind knot, there isn’t the necessity to rebuild the entire terminal end of the leader. And the ring makes a nice stop for your split shot or sink putty.

Bud: Wintering in California and fishing the salt here, is there any kind of cross-fertilization that goes on in your approach to angling in that environment and your approach to fishing the Columbia, and likewise the other way around, from a freshwater trout fishery to the surf zone?

Steve: Probably. I suspect that the crossfertilization of ideas mostly takes place in a preconscious portion of the brain, on a subliminal level. We’re always picking up signals through experience and observation, not all of which are consciously registered, yet all combining to affect our actions, our approach.

Bud: Like most guides and committed anglers, you have a major interest in the issues involved in the conservation of fisheries and the constant battles over water in the West. How do those issues play out on the upper Columbia, and what lessons have you learned there that Californians can (or need to) take to heart?

Steve:O boy. This is a difficult question to answer briefly. I wrote Upper Columbia Flyfisher in an attempt to define the nexus of this question, and in the attempt, I found the problem, at base, to be systemic, then fractal.

The lesson I’ve learned? Because the problem is systemic, but then fractal, replicated at every level, I’ve learned that it is impossible to take on the world, but it is possible to affect change in your own bathtub. Ask any American if they would die for their country, and I think most would answer that they would, yet how many of us contribute 15 minutes a week, or even a month, to write a Congressperson or fish-and-game manager concerning an issue? Talk is cheap.

Ours was meant to be a participatory democracy. Our government and its priorities are a reflection of who we are as a people. Nothing more, nothing less. If we perceive our government as an entity separate from the people, rather than as a functioning arm of the people, somehow evil and out to get us, that is what it will be. The nihilists and plutocrats will win the day. A handful of billionaires will rule the land and ruin the commonwealth. Without commonwealth — those things we hold in common, our infrastructure, our public lands and waterways — there is no E Pluribus Unum and there is no greatness. And sadly, we see that happening. I see us on the verge of losing much. Perhaps all, if we don’t drastically reprioritize.

Knowledge and our environment need to be our main priorities, in my opinion. I believe we must make educating our people and restoring the environment our number-one goal as a nation if we are to survive and, indeed, create authentic wealth for our people. And we need to spare no expense in doing so, even if it means cutting back on trickle-down welfare programs for billionaires.

But I’ve also learned that words precisely directed can have great power to make things move. Wise words carry light, and those who must operate behind a veil of secrecy wither under light. My advice to Californians: stay informed. Gather a group of angling friends or your club, adopt a local stream, and work diligently to maintain its integrity. Become acquainted with your local fisheries managers and become e-mail gadflies to them and anybody else who needs to know your point of view. Participate. Shine light. As citizens, it is our duty. Our grandchildren will thank us for it. And the fish will thank us for it.

Bud: I’ve seen where you’ve written “though they are made of fur & feathers now, I’m still fishing baits, still a shameless bait fisher at core” and that “I am not an entomologist. (I am a bait man.)” How does that sense of identity affect your approach to fly design?

Steve: An artificial fly is a “bait.” As an angler, my primary interest and goal is hooking and fighting fish. Sometimes I kill one and cook it. There are many peripheral aspects of our sport in which one might become interested to the point that the particular interest becomes the primary goal — rod building, enjoying the scenery at new locations, fly-fishing literature and history, designing flies using the latest materials, the fellowship of belonging to a club, the study of insects. Fly fishing is fairly unique as a “sport” in that it contains so many aspects that might be taken up as singular interests and areas of expertise. And I am interested in these things, more and less, but only as far as I need to be in order to satisfy my primary goal. I love designing and tying flies, yet the primary goal, to create a workhorse bait that fish will attempt to eat, most always informs the tying. Fish don’t eat artificial flies, but they do eat live baits, so I try to make my flies present and act like live baits. I think that’s what most of us do.

Bud: You also have been influenced by two fairly traditional approaches to fly design: James Leisenring and Vernon S. Hidy in The Art of Tying the Wet Fly and Fishing the Flymph and Charles Brooks in Nymph Fishing for Larger Trout. Two of the things that are most striking about your fly designs are the way in which the soft-hackle style lies at the center of most of them and the way in which they look in the water, when wet, which seems to be of prime importance in how you think of them. The Big Sur Shrimp that you mention in “Lonesome Coast” is basically a soft-hackle streamer, and your nymph imitations reflect the soft-hackle style. Many fly tyers and anglers these days seem to have drifted away from the soft-hackle approach. What are they missing?

Steve: I found the elegant simplicity of the fly designs and the principles contained in Leisenring and Hidy’s approach to be fundamentally solid. Put into practice, the positive result was immediate for me. What The Art of Tying the Wet Fly teaches, in essence, is the basic, organic principles of bait design and presentation. The fundamentals of our sport. Anybody who is “drifting away” from that lacks firm footing in the stream and is possibly being swept away by a trend. That can happen if one doesn’t spend enough time standing in the stream, observing, finding balance.

And the principles need not be limited to traditional soft-hackle concepts, which Charles Brooks illustrates in Nymph Fishing for Larger Trout, which is still holding up beside The Art of Tying the Wet Fly as one of the two most influential and useful books I’ve yet read on the subject of fly fishing. From their pages, Leisenring, Hidy, and Brooks emerge as getters, organic angler-observers whose fly designs were an indigenous response to what their home waters dictated they need as good baits.

Brooks took the traditional style out of the box, applying a distinctly Western slant, his response to the water he fished, the brawling freestones of the West — which contain big nymphs and honker trout. And this leads back to your question about the transmigration of influences between the California surf and trout fishing in Washington. Keep in mind that there is no great difference between the profile of a swimming shrimp and that of a swimming nymph. Stretch them out, and you see that most shrimp and insects are basically cigar shaped, elongated or compressed. In both cases, I am fishing moving water. In both cases I want my fly tickling along the bottom. Many of the fundamental principles apply, and it’s hard to get too far away from the basic shape of the critter, which the soft-hackle design simulates well, enhanced by motion and obfuscation.

Bud: You’re a member of the International Brotherhood of the Flymph, not a group much devoted to the use of foam and plastics in fishing flies, and you link to the Web site of Don Bastian, perhaps the nation’s premier tyer of traditional “Bergman” style wet flies. But however much your approach to tying flies may have a traditional base, your fly designs are also quite innovative ties. How do you see the relationship between tradition (as “bait” fisher), innovation, and observation in designing and tying flies?

Steve: It’s true that there are some among the Brotherhood of the Flymph who are keen historians and keepers of the faith. Yet the BOTF is actually an expansive, creative group, and they are kind enough to allow room for me. I’m humbled, because its members, to my eye and thinking, represent some of the best bait-design artists out there. And that is the reason for the Don Bastian link on Soft~Hackle Journal: to show readers a level of artistry that represents the best of tradition.

All that stands to enter into tradition was once innovation, the result of observation, and what stands is what has proven authentically useful. What we call “tradition” is simply the record of what works. So it is never old and always informing what we do. We stand on the shoulders of all who came before us and are connected to their achievements. And for me, prone to melancholius habitus, Bastian’s flies represent an idealized New England, an idealized vision of our sport, which may never have existed in reality, yet somehow serves to tinge my approach to angling, maybe the result of those things the Yankee men of my youth impressed upon me — beautiful myths.

Bud: We haven’t talked about your writing yet. You have written both Upper Columbia Fly Fisher and short stories that have appeared in anthologies. Any guide and fly designer who quotes Henry James on his blog obviously has literary roots that go deeper than the classics of angling literature. How did you come to writing? What role does the Internet now play in sustaining that calling?

Steve: I blame the writing on my grandmother Ariel, who taught me to read and love books, and that love was further advanced by teachers such as Mrs. Green, Mrs. Flint, and Mr. Fox. For the last twelve years, I’ve been enrolled in literary and editing courses. I’ve always been a reader, though, busy chasing a buck while raising a family, I came late to writing as a serious endeavor. And yes, the Internet does play an integral role in the process. Like it or not, and to say the least, a computer hooked up to the Internet is an essential tool for anybody seeking to publish nowadays.

Bud: More broadly, I can see that given your somewhat nomadic style of life, an Internet presence can be something of a necessity. But I wonder if the flip side of that isn’t also true — that the ubiquity of the Internet makes it possible to move about more freely in the so-called “real” world while maintaining a constant “presence,” of a sort, a trace, as both a writer and a business owner, in a place that is everywhere and nowhere.

Steve: Yes to both of those thoughts. I use the Internet as an almost organic extension of sorts. It functions as a portable office: a typewriter, research library, storage cabinet, and communication device, all in one. You and I are writing this interview, you in New York, me in California, and we will conceive it, write it, and move it to a print deadline more quickly than it would take to send an initial query, the spark of the idea, by mail. And as a business tool, it is invaluable. I don’t spend a cent on advertising, because the majority of my clients come through the Soft~Hackle Journal, which functions as an engaging billboard, but also my pet creative project, so I’m able to mix business with pleasure, which I like.

Bud: I always end with what is, by now, a tradition: the Silly Tree Question. If you were a tree, what kind of a tree would you be?

Steve: Well, I admire the yew tree, which grows at timberline and lives to great age. The yew produces a fragrant, beautiful, and useful wood, once prized for the making of fine hunting bows able to launch arrows deep enough into a bison to penetrate its vitals and bring it down. But the yew is a rare and solitary tree, and that is not me exactly.

As well, I like the western red cedar. Its wood, too, is lovely, fragrant, lightweight and useful, indeed, so useful that it is considered sacred wood, a gift from the Creator. Natives of the northern coast carve their totems from red cedar, and early fly fishers in the Northwest chose it for building their rods. But I am uncomfortable bearing a mantle of sacred boughs, and cedar breaks easily under stress.

I’m particularly fond of the sugar maple, native to my birthplace and coming to brief and fiery glory in autumn, my favorite season. The pioneer surf fishers of Cape Cod carved their long rods from maple saplings, as did the early fly fishers of New England, the resourceful men of the country who didn’t have the money for greenheart rods. When I was in the third grade and my mother locked up my fishing gear in the shed as punishment for ditching school three times in one month to go fishing, I carved a rod from a maple sapling and set it up with stuff pilfered from my dad’s tackle box. I kept the outfit hidden in the woods, and it served me well until my gear was let off restriction. But I now live in country where the sugar maple seems an outsider, exotic and out of place.

I think that I would like to be a mountain dogwood, which has a broad range and is found in both the East and the West, often in view of rivers. The dogwood is rarely the tallest tree of the forest, most often beneath a canopy of grander trees, yet it is limber, not rigid, and seldom seen to blow down in a storm that might bring down the stout oaks towering above it. The dogwood is a reserved and graceful tree, usually content to remain out of the limelight, yet for a short time each year, when it sets its white-cross blooms down along the river road, signaling the beginning of the drake season, the dogwood is the most hopeful of trees.