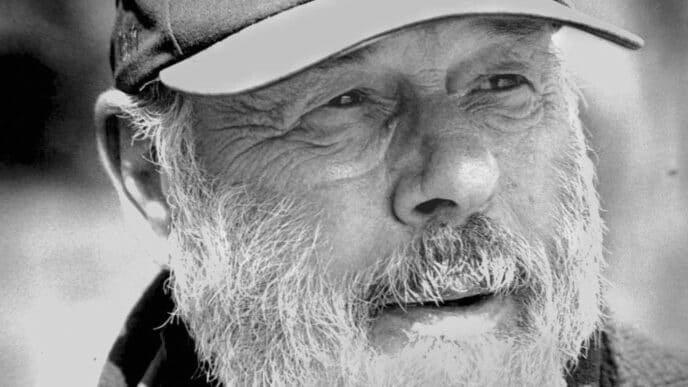

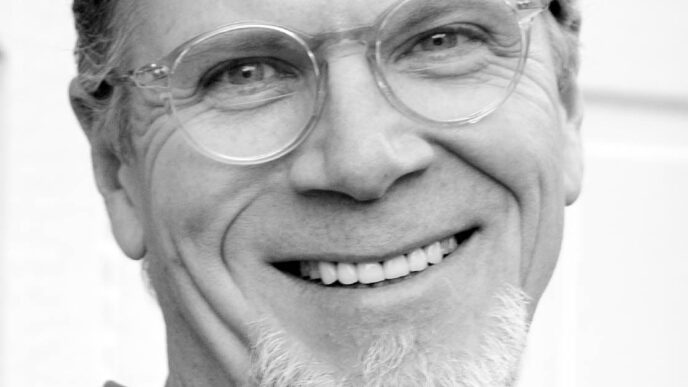

If you’ve read California Fly Fisher for any length of time, you’ve read the outdoor writing of Bob Madgic. If you’re old enough, you also may have read the high-school textbooks written by Robert F. Madgic, Ph.D. They’re the same guy. Since his retirement from the education world, Bob Madgic has continued to educate California readers, especially about what he once called “wilderness values.” We talked to Bob about his two careers, one as an educator and another as an outdoor writer. Or maybe it’s one career — as a writer — with two parts, both focused on education.

Bud: Let’s begin at the beginning. How did a private-school kid from Deerfield Academy and Amherst College in Massachusetts end up working in public education in California?

Bob: You are correct in identifying education as the unifying thread in my life. Writing, though, is hardly my first or even second career, except in the loosest sense. I like to say that I turned to writing after I retired from a real job in public education as a means to keep my mind deteriorating at a slower rate during these senior years. Writing is thinking, so to write is to clarify and express my thoughts on myriad subjects, which I find important to do. So yes, I have spent considerable time getting things down on paper for the last two decades, and in many respects, this has proven to be perhaps the most rewarding aspect of my life. It’s just a good thing that I don’t have to rely on income from it.

Now to my beginnings. I was anything but a private school kid. (I know what those are.) Neither of my parents graduated from high school, so my background was anything but privileged. But one key opened up many doors for me — sports, mainly baseball. I was a good athlete along with enough smarts to compete in the classroom, and mentors showed up. One was a Harvard recruiter looking for student-athletes for his alma mater. Given my mediocre high school, we agreed a transition year in prep school made good sense, which a couple of other local athletes had done. So with his guidance, I ended up as a fifth-year senior at Deerfield Academy. The headmaster there, being an Amherst College man, coyly redirected me to Amherst, much to the displeasure of the Harvard guy. It all came down to being a good baseball player. My message: if anyone wants a child or grandchild to get into an elite college, have them shoot hoops and take batting practice. Let the kids who can’t do much else practice for the SATs.

Upon graduating from Amherst, I got married and spent a year in the admissions office, which pointed me to a career in education. My wife and I then headed west — camping all along the way — where I enrolled at Stanford to get a teaching credential and master’s degree. We chose to stay in California and not return to New England, as originally planned. One factor here was an ambitious professor on the lookout for doctoral students. With his influence, I returned to Stanford, where I earned a Ph.D. in education and an undying love for Stanford football.

Bud: I know that a professional education and then the professional responsibilities that result from it can all but take over your daily life. Where, when, and how did fishing, and especially fly fishing, enter into this narrative?

Bob: In that postgrad year at Amherst, with sports no longer a part of my life, I took up fishing the local waters with a lot of energy and worms. I had fished as a kid, so this was not new. Once at Stanford, with a growing family in tow, I put aside the fishing rod in favor of trying to pay bills, helped in part by writing. It seemed like I had a knack or drive for initiating projects. No sooner was I teaching American history to high schoolers then I conceived of adapting Amherst’s “Problems in American Civilization” to texts for secondary classrooms. This became “The Great Issues Series,” published by Scholastic. It led to co-authorship of an American history textbook, The American Experience, published by Addison-Wesley. Unlike today, public education was highly supported in the 1960s, so I was able to get other innovative curriculum texts published. But after leaving Stanford, I became a high school administrator, and other than an occasional professional article and many memos to teachers, I basically stopped writing.

On the other hand, my fishing got a major boost around this time. In the middle of my public school employment, I took a leave of absence for what I hoped would be a year, but which turned out to be only three months. The agenda was a family sojourn in New Zealand. A personal objective was to transition from a worm fisherman to a fly fisher, given this country’s reputation. I found New Zealand’s waters and their trout a bedeviling mystery, though. But our sons and I finally began catching fish on flies, mainly by adapting to the fish’s feeding schedule in the waters where we had rented a home — that is, in the dark of night. Talk about an introduction to the art and craft of fly fishing!

Bud: After you retired in 1993, you authored Pursuing Wild Trout: A Journey in Wilderness Values (River Bend Books, 1998), A Guide to California’s Freshwater Fishes (Naturegraph, 1999), Shattered Air: A True Account of Catastrophe and Courage on Yosemite’s Half Dome (Burford Books, 2007), and most recently, The Sacramento: A Transcendent River (River Bend Books, 2013). For someone with a Ph.D., writing often is simply a professional obligation — a job requirement — but you’ve treated it more like a calling. What was your own education as a writer?

Bob: You nailed it by referring to my writing as a calling. What integrated my background in education and writing were two other overriding interests — conservation and fly fishing. The latter quickly became my primary focus in writing, thanks in large part to California Fly Fisher. So one might say that I used writing about fly fishing as a vehicle to educate others on conservation. In any case, these four elements have dominated my life ever since.

Bud: Where did your commitment to conservation come from?

Bob: In the early 1970s, we acquired a cabin in the Sierra Nevada, which got me back into fishing. But alongside that came an abiding interest in whitewater rafting, triggered by the presence of the Stanislaus River flowing in the canyon below our cabin. I got my own raft and reveled in this sport, joined by many foolhardy friends and family members. Then this nine-mile stretch of glorious rapids with names such as “Widow Maker,” “Death Rock,” and “Devil’s Staircase” was destroyed by an unnecessarily gigantic New Melones Dam. The resulting reservoir flooded 29 miles up into the canyon, right up to the rafting put-in. It was a horrible loss for many of us, and from this point on, I dedicated myself to trying to prevent more such losses. This calamity also showed me that such matters are often resolved in the political arena, which means winning at the ballot box. So add another dimension to my writing — political advocacy, which has primarily taken the form of op-ed pieces for our local newspaper, an occasional letter in a magazine, and the like, only occasionally slipping something political into my other writings.

Bud: Let’s look at your four books a bit more closely. What motivated you to write Pursuing Wild Trout? To put it another way, all nonfiction prose does some kind of work. What work did this book set out to do, and why did you think it needs doing?

Bob: Getting a first article published in California Fly Fisher initiated my foray into outdoors writing. Many more articles followed. After I retired, with lots more time on my hands, I had the idea of describing my outdoor ventures in a book. It became Pursuing Wild Trout. I had no prior training in this kind of narrative writing. I just detailed my adventures and misadventures, which included many comedic dimensions, such as getting lost in the dark, exposed to harsh weather with no warm clothes, and similar quasi-disasters. I think readers especially enjoyed hearing about the many times I almost got killed or seriously wounded. I also used this anecdotal approach to develop a thread about my own growth or “journey” in becoming an advocate for the natural world and for what I called “wilderness values.”

Bud: Pursuing Wild Trout is a personal, autobiographical work, while A Guide to California’s Freshwater Fishes is pretty much a compilation of objective information. How did you conceive of the relationship between the two, which came out in succession, and the relationship between the work that each book set out to accomplish?

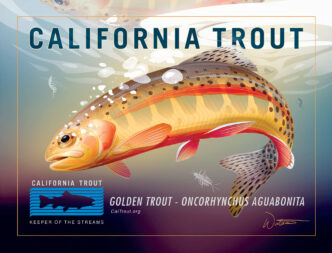

Bob: The short answer here is that a publisher said she wasn’t interested in publishing Pursuing Wild Trout, but liked reading about the fish species in the book. I asked, how about a guide on fish species? She said yes, and the book thus got launched. Fortunately, I had an artist in the wings raring to go; he painted over 65 outstanding fish images in less than three months. This book does expand on my personal values in important ways. In Pursuing Wild Trout, I wrote that the kind of fish I was catching and how I was catching them began to matter. On the scale of wilderness values, protecting native species is at the top of the list. A Guide to California’s Freshwater Fishes advances such themes, buttressed by a need to preserve natural habitat.

Bud: Shattered Air represents a totally different kind of writing from what you had done up to that time. How did this book come about?

Bob: After writing many articles for California Fly Fisher and my two books on fishing, I was looking for the next writing project. At this time, John Krakauer’s Into Thin Air and Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm were riding high. They spurred me into recalling a lightning calamity on the top of Half Dome that got a lot of press at the time. The son of my secretary was involved and could easily have been killed, so I had some connection here. I mentioned this to a bookstore manager, and he replied, “Well, you know, it will be a bestseller if you write a book on it.” I drove away with images of fame and fortune filling my head and decided then and there to write this book. Since it would be the first disaster book featuring lightning, and Yosemite was the setting, I thought it couldn’t miss. Still, it was a tough sell to agents and publishers, primarily because I was not that accomplished or talented a writer. Our daughter framed the issue most succinctly when she said: “Dad, this is a major-league project with minor league talent.” I now really wanted to write this book to show her I could do it. Shattered Air never achieved widespread acclaim, like Krakauer’s and Junger’s books, but it has been embraced by a wide segment of the outdoors community and other readers.

Bud: Lightning obviously isn’t a hazard that just those heading up to mountain summits face. I know you published an article about the hazards of lightning in the May/June 2006 issue of California Fly Fisher. For a quick recap, however, as we wander around carrying 9-foot electrical conductors, what should we be aware of when a thunderstorm approaches?

Bob: The best precaution is to check weather reports and avoid being out when a thunderstorm is apt to roll in. If one begins to form, even by cumulus clouds beginning to combine in an otherwise clear sky, take heed and leave the scene. Lightning can strike well before the storm actually arrives and for up to an hour after it has presumably ended, literally “out of the blue.” My article cited the experiences of a Montana fishing guide and his clients who got struck as they were heading back to their vehicles ahead of the storm, or so they thought. The singular message of Shattered Air is that if caught in a thunderstorm, do not take refuge in the wrong kind of cover, like in or under rock enclosures and overhangs, under a tall tree, in a baseball dugout or picnic enclosure, or under tarps with ropes affixed to trees. Hiding out under a boat would be a terrible choice. Lightning seems to be drawn to such enclosures, as many recent Boy Scout episodes show. And oh yes, if the air is buzzing and there is a bluish glow pulsating at the tip of your heaven-pointing graphite fly rod, or you feel an unusual jolting in your arm while casting, or the hairs on your arm, neck, and head are raised and tingling while you are netting a fish, you are in deep doo-doo. If any of this has happened to you, consider yourself lucky to be reading this and able to decipher it.

Bud: You said that fly fishing has been an activity that has allowed you to express your values through writing. Has the practice of writing affected your angling? How would you describe their interaction?

Bob: When I present talks to fly-fishing clubs, I usually say that “I am a better writer than I am a fly fisher, and I’m not that good a writer.” Unfortunately, this is the case on both counts. I have many far superior fly fishers as friends, to the point of personal embarrassment when catch rates are totaled up. I already said that in the world of writing, my abilities are down the charts. But I probably enjoyed some modest successes by writing about what I truly love about our sport. I am not a flyfishing tactician, one who thrives on the challenge of using 20-foot leaders and size 18 flies to hook paranoid Hot Creek trout that are desperately trying not to get hooked yet one more time. I prefer finding trout that are happy to see me, which usually involves a trek of some kind.

I recall one trout that I hooked in a small pool in Alger Creek after a really tough two-hour jaunt. It was a beautiful golden-rainbow hybrid, about 13 inches, and I really wanted a picture of it. I lifted it out of the water and lowered it to the ground, where it flopped all about and dislodged the hook. I tried to grasp it in my hands, but it thrashed around and flopped down the rocks and back into the pool. Crushed at losing the photo, I halfheartedly made a desultory cast in the same pool, and lo and behold, that same trout hit it as hard as the first time. This time I got my picture. This is the kind of fish I like.

When I write about fly fishing, I typically emphasize place more than tactics and focus on what I find personally absorbing. My favorite article that I wrote for California Fly Fisher was called “Secret Places.” In it, I described four pools in different waters that I have revisited many times across the years and that became my secret places. I wrote something like this: When you have your own special water, whatever its form, no one else knows this bit of life as well as you do — its moods, idiosyncrasies, mysteries, and rewards. By probing ever deeper into what’s there, one becomes fully immersed in it, a part of it. Compare this with a float trip, where you quickly pass by alluring runs, pools, eddies, and glides with only the briefest of introductions.

Bud: Longtime readers of California Fly Fisher know you as an angler who wrote about the rivers of the eastern Sierra, but more recently, you’ve been writing about the Sacramento River near Redding. What prompted the change?

Bob: This is an easy one. We moved. We long had a vacation home in the June Lake Loop, which explains my many articles on the waters there. Home was in the Bay Area, where we lived for 35 years. I thought I could never leave there, even in retirement. But a stay in a B&B on the Feather River a few years back left an indelible and persuasive image — living on the water. It turns out that the Sacramento River is about as good a place as could be found for a home on the water, in my view. I discovered this while canoeing down through Redding and saw all the homes along the river. Like Brigham Young, I announced, “This is the place.” Fortunately, my wife agreed. So after many years when a 14-inch fish was the best of the season, I now am able to fish below our property and cast to hundreds of fish that average 16 inches. Add Manzanita Lake less than an hour away, and I live in a fly fisher’s nirvana. The climax to this story is the publication of my new book, The Sacramento: A Transcendent River, which was in the works for many years.

Bud: In this book, you write: “Despite its vital significance” as a water resource for both the state’s human population and its natural ecology, “no major publication has yet been produced on the Sacramento River,” which is a prime reason why you wrote the book. In it you also write: “I soon realized I was dealing with many of the biggest and thorniest issues facing California today.” Briefly, what are those issues, and how do you think your book helps illuminate them? And why do you feel qualified to write such a book?

Bob: The most pressing issues facing not only California, but the world, involve water. As I write in the preface to my book, “the collective water requirements of those downstream, human or otherwise, already exceed that which is passing by.” Just this past August, San Joaquin farmers filed a lawsuit to stop more water from being sent down the Trinity to save salmon. They argued that they need this water to feed the nation. Environmentalists, fishing groups, and others argue that the very well-being of the Sacramento River and all of the creatures it sustains, including many endangered species, depends on the quantity and quality of water flowing into the Delta and out to the ocean. There are proposals for yet more human alterations, such as raising Shasta Dam and building tunnels above the Delta to intercept water and send it to the Central Valley. There simply is not enough water to meet all demands, many of which have been artificially created with the federal and state water projects that transformed southern deserts into gardens and metropolises.

The main theme of my book is the power and beauty of a natural river. Many of the 190 photos forcefully illustrate this theme. They are meant to evoke a visceral reaction, prompting the reader to conclude, yes, such gifts of nature are special and must be protected. The book takes a very definite position — the river should retain its natural character wherever possible. And it we should also restore features such as meanders, flooding, and riparian foliage. The health of the planet depends on the health of rivers, and healthy rivers are allowed to do as nature intended.

Why am I qualified to write such a book? I have long been concerned that so many treatises on environmental issues are written by scientists, researchers, government officials, and the like. While such documents may present the most relevant research and information, they are generally not written for a general audience. I believe that my background as an educator gives me exactly the qualifications needed to produce a book that makes ecological matters accessible and engaging for a broad audience. The intent of this book is not only to inform, but to inspire, and that’s something an educator strives to do.

Bud: Here we are already at the obligatory Silly Tree Question. If you were a tree, what kind of a tree would you be?

Bob: My wife volunteered poison oak, but she claims this was in jest. My response here is not only a specific kind of tree, but a particular specimen. It’s a juniper growing on the side of a granite dome near our June Lake house. It is distinctively twisted and gnarled, its roots still clinging in the meager crevice where they get nourishment. It’s my favorite outdoor image, not only for that area, but in general. I hope to keep hanging in there like this wonderful tree is doing, with its conviction of knowing where it stands.