It’s not when you come to fly fishing — it’s how, and why, and what you do with the experience. What Barbara Klutinis has done is create the film Stepping into the Stream, an introduction to fly fishing that, while directed at women who might become interested in the sport, conveys its appeals so powerfully and poetically that, as with Jeffrey Pill’s Why Fly Fishing (see the May/June 2008 issue of California Fly Fisher), it more than answers the “Why” question for anyone who asks it. The film should become a go-to resource for anyone who wants to understand fly fishing’s appeal or explain it to others.

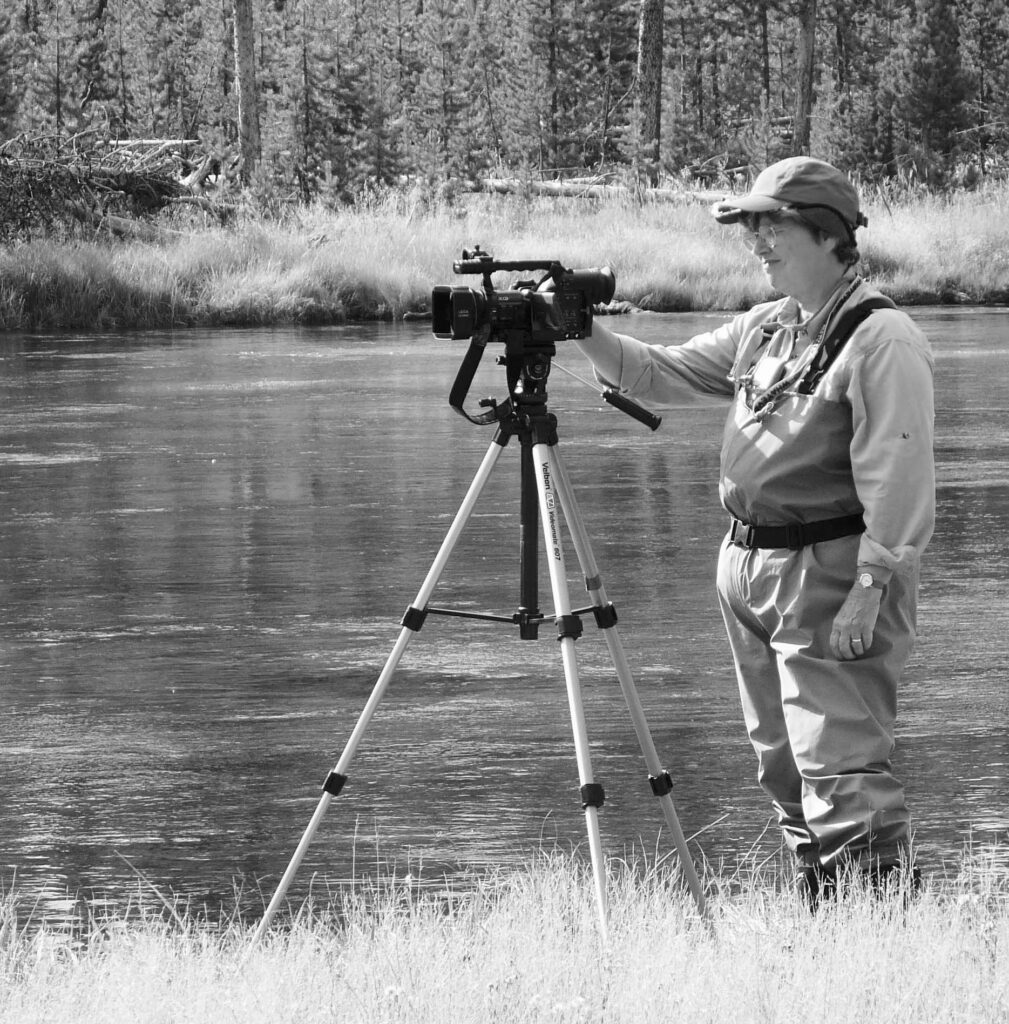

Barbara Klutinis is a retired teacher of film studies at Skyline College in San Bruno and San Francisco State University, and an experimental filmmaker whose work has appeared to acclaim in many film festivals. She has now brought her skills to conveying what is so frequently addressed and so seldom addressed successfully in much of the literature of fly fishing — the spiritual and philosophical elements that are such an integral part of the sport — along with its ordinary pleasures (and frustrations).

Bud: I gather that you started fly fishing at the “empty nest” stage of your life. What specifically drew you to fly fishing, and why fly fishing, rather than, say, running for governor or raising orchids?

Barbara: Yes, I started fly fishing when my teaching career seemed to be winding to a close and my first son was leaving for college. My husband’s sister, Peggy Ratcheson, took me fly fishing in Montana. They have property on the Bitterroot River. When I stepped into the river — well, I say it in the opening of the film — my life changed forever. When I returned to San Francisco, I started looking for a women’s club, mainly because my husband didn’t fish and I thought it would be fun to fish with other women. I joined the Golden West Women’s Flyfishers, the GWWF.

One of the women in my fishing club suggested that women who join our club and who stick with it are usually going through some kind of transition. I found that to be so. Some women had lost their husbands through death or divorce, some women were experiencing the “empty nest,” and still others had finally found the time to do something for themselves. Indeed, those are the women with whom I am still fishing.

Why fishing? My dad used to take me fishing on the TVA lakes (Tennessee Valley Authority) when I was young. It was a time I felt most connected to him. I had never thought of myself as an “outdoorswomen,” even though I have been an avid skier since my 30s. Now that I have been in this sport for 10 years, I have discovered that there had always been a part of me that had been crying out for a closer connection to nature, a part that yearned for crisp, foggy mornings on a river and quiet evenings on quiet streams.

Bud: One of the strengths of the film is the way it both explicitly discusses the many various appeals of the sport and uses the medium of film to invoke them — appeals that pretty much cover why those who love it do so, and appeals that do not involve considerations of gender. The film’s principal audience, though, is women who might be attracted to the sport. What motivated that particular focus?

Barbara: I had seen a lot of “guy” films — you know, someone holding a can of beer in one hand and a spinning rod in the other, shouting “Whoopee . . . look at this big fish I caught!!!” Most of the emphasis seemed to on the adrenalin rush of the strike (which I can totally relate to!) and on hauling in the fish. There are also a lot of fishing shows on TV, but very few of them feature women anglers. I wanted to give women a presence on the river, and I wanted to present a different perspective.

I came to fly fishing very late in life, in my 50s, not unlike many of my GWWF friends, who finally have time for this now that their children are grown. My hope is that maybe some other women will take confidence from this film and find the courage in themselves to try something new.

Bud: In a short review of the film, Anne Vitale notes that one way to view it is as “a short history of women’s fly fishing” and thus as a contribution to “the general lore of fly fishing,” a contribution that is “long overdue.” You came to fly fishing in the middle of that story, so to speak, whereas women such as GWFF founding members Fanny Krieger, who is a wise presence in the film, and the wonderful Dorothy Zinky, who is featured in the additional interviews included with the special features on the DVD, have been there for the long haul. How has your experience differed from theirs, and what sort of future do you envision for women in fly fishing and for women’s fly-fishing groups?

Barbara: I guess most of the pioneering work was already done by the time I found fly fishing. Yes, Dorothy and Fanny are truly amazing movers and shakers of the sport in the name of women. I am fortunate to know them and to benefit from their collective experiences. When I first started fishing, I still experienced, to a small extent, being ignored in fly shops and unable to find any waders that were made for women except those offered by Simms. In the last 10 years, there has been an explosion in women’s products, and now we get our due attention when we go into fly shops. I can still cite a lack of media attention around women in the streams, and that is why I made the film.

I see our future filled with even more women, but I hope that young women who are raising their families can find a little time to get away to the streams or take their children fishing with them. There was a member of our club who used to bring her husband and one-year-old son on some of our outings. I loved seeing them with the kid in the backpack, wading a stream and showing a fish to their son, who responded with much glee.

There seem to be a lot of women’s clubs springing up around the country, largely due to outreach by the International Women’s Fly Fishers (IWFF) and the influence of respected women such as Joan Wulff, Lori-Ann Murphy, Maggie Merriman, and many others. My hope is that the women’s clubs will continue to expand, even in this economy.

Bud: One of the concerns that all fly-fishing organizations share is the relatively advanced age of their membership and the worry that younger people aren’t entering the sport in numbers sufficient to sustain it and the conservation efforts that are a part of it. What sort of future do you envision for young women in fly fishing?

Barbara: The film addresses this issue in one aspect in that Lori Ann Murphy talks about how women don’t take a lot of time for themselves while they are raising children. When they finally have time for themselves, they are older — hence become the older makeup of our groups. It is a dilemma, but not unlike other dilemmas that face women in the workplace, as well. It’s a matter of balance, I suppose: raising a family or having a career and also finding time for yourself. I do think that young people are picking up the gauntlet of conservation, and if that is what will bring them to commune with nature and maybe discover the sport on their own, then our future looks good.

Bud: The film also manages to convey a lot of basic pragmatic information about fly fishing, from equipment to river types, but its principal topic indeed seems to be the basic appeal (or may kinds of appeal) that characterize the sport. The section I found most riveting involves accounts of the ways in which fly fishing changed lives, as you say it did yours — especially Simone Geoffrion’s account of her realization that her high-pressure job was literally killing her. That sort of conversion experience is by no means related to gender, either, but some guys fish because that’s what their father and grandfather did — because that’s what guys do. Is there a reason that so many of these women’s stories are so particularly vivid?

Barbara: If you talk to a lot of women fly fishers, you will find that many of them got their first taste of fishing from their fathers, as well, not unlike their male counterparts.

Why are their stories so vivid? When Simone first told me the story of her heart attack (and the film only has a small part of that interview), she had me in stitches. She has a hilarious account in the outtakes. But what impressed me the most was her honesty and directness, what she learned from the experience, and her articulateness. I looked for that same quality in the women I interviewed. Lori Ann’s and Jean Williams’s accounts of their work with Casting for Recovery participants were equally poignant because they are caring, giving, and sensitive people and knew how to convey that in a simple, but meaningful way.

And fly fishing does change lives. Many of the women I know who volunteer at Casting for Recovery workshops often speak of the incredible transformations that occur with breast cancer survivors at these weekend retreats. The participants feel the healing currents of the water; they experience nature with a rawness and tenderness that is new to them. They relish the attention given to them by the volunteers, and they seem to find a kind of relief and comfort in these spiritual hours on the river. For a brief time, they forget about their diagnosis, the chemo, the side effects, the future . . . and learn to focus on the moment.

Bud: I’ve been focusing on the content of the interviews, but I’d also like to focus on the film as a film. It’s quite stunning visually and in the structure and rhythm of its composition. As a filmmaker, your work was chiefly in what is pigeonholed as “experimental” film. The documentary form, employing interviews and historical materials, as Stepping into the Stream often does, is a considerably more staid, although also obviously more appropriate for the film’s message and audience. What did your considerable experience in experimental modes of filmmaking contribute to the making of Stepping into the Stream?

Barbara: I had been wanting to make a more conventional film, partly because I wanted to challenge myself in a new way. When you work in a medium such as experimental film that relies largely on interpretation, it is a challenge to approach a piece of work that simply . . . is . . . without adding too many layers.

Film is like a tapestry, and the trick is to interweave all the parts into a cohesive whole. The challenge for me was how to intertwine the lyrical images, poetry, prose, and music with the more conventional “talking head” interviews. One also risks cliché by using the metaphor of rivers and life. The art is to combine all these elements into something that makes some kind of inherent sense on a nonverbal level.

Bud: Earlier, I distinguished between the explicit content of the film and what it invokes as a film. One “Wow” moment is an example of that: At the end of the section on the way fly fishing has changed women’s lives, there’s a series of long, slow panning shots along the Fall River, accompanied by music by Elise Lebec and by a poem by Judith Brown. The passage ends, just after the poem ends (“the water boils / as a thousand trout rise / to celebrate their good fortune”), with a single trout leaping in the calm water.

As you just said, there’s more in Stepping into the Stream than just what the people in it say or what the images depict. Can you address what a film like this can do that talking or writing about fly fishing can’t?

Barbara: You described my favorite part of the film, because in the Fall River section is where things all came together for me. Elise described the musical score that she composed for this section as a “journey that accompanies the journey of the film into the lives of these women.” Elise’s husband, Mat Baldwin, designed the awesome motion graphics for this section, incorporating the floating poetry of Judith Brown. The Fall River itself is such a poetic river: the way the views change from one curve to the next, the way Mount Shasta overlooks every turn, the way the river encircles the landscape.

But getting back to experimental film and your question . . . film is like poetry: It has rhythm, metaphor, and visual imagery. Film has the advantage over other art forms in that it can play with or alter time and movement. Many of my earlier films have played with the concept of slowing down time and movement to let the viewer experience the poetry of motion inherent in movement itself.

Before the digital age, many filmmakers like myself used an optical printer, which is a device that can be used to rephotograph images, one frame at a time. It has a Bolex camera on one end and a projector on the other end, anchored to a rail that holds everything on an even plane. In the space in the middle is a metal frame that can hold one frame of film in place, and the filmmaker can work with that one frame in a number of different ways, in a method akin to animation. Thus, the optical printer allows for the passage of time to be either speeded up or slowed down, allows images to be combined in ways that are abstract and unusual, allows for a moment in time to be frozen, one frame at a time.

Today, digital editing programs such as Final Cut Pro can do the same thing, only much less laboriously. My film Wind/Water/Wings examined the poetry of jellyfish slowly moving in a tank at the Monterey Aquarium and a balloon lifting into the sky with the wind. Journey, Swiftly Passing, about my father’s death, was made from hand-colored black-and-white-negative 16-millimeter film, which I reprinted, three times in different stages. All these films examine the passage of time and movement in different ways, on different planes.

To some extent, I brought this technique to Stepping into the Stream, for many of the passages are slowed in time so the viewer can experience the lyrical motion of the green grasses in the Fall River or the resistance of the water to my wading in the opening. For the yogini poem sequence, which shows a woman casting, I also slowed the casting down so that one could experience the cast itself. When Elise was composing the music for this sequence, I asked her to compose something “Eastern” sounding, since yoga is an Eastern concept, and she came up with this atonal piece that responds to the narration in counterpoint. Because the poetry was so connected to the imagery, I wanted to put them together in the same frame — hence the box with the yogini, with the text below it.

I suppose the sum of these parts is that the viewer, I hope, experiences on a subliminal level the poetry of the cast, the flow of the grass, the feel of the water as one walks through it. I wanted to create the antithesis of the slam-dunk editing style work that is so in vogue now. The film is restful and meditative, kind of like fishing. To quote the Russian Formalist critic Victor Shklovsky: “And so, in order to return sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art. The purpose of art, then, is to lead us to knowledge of a thing through the organ of sight instead of recognition. By ‘estranging’ objects and complicated form, the device of art makes perception long and ‘laborious.’ The perceptual process in art has a purpose all its own and ought to be extended to the fullest. Art is a means of experiencing the process of creativity. The artifact itself is quite unimportant.”

Bud: In other words, art makes us see familiar things anew. Perhaps to phrase the question in a different way, what is it with Barbara Klutinis and water? In addition to Stepping into the Stream, you’ve been involved in a project called Pools (with Barbara Hammer, 1981) and a multiphase project called Estuary (with Rebecca Haseltine, 2004–6).

Barbara: I’m an Aquarius. I’ve always been drawn to water: the gravityless way things move in it, the way it magnifies objects and refracts light, the way moving water pushes against things that move through it, the out-of-body perspective water imparts when you are in it.

The subject of my first real “art” series as a still photographer involved women in silky gowns floating in water in an indoor swimming pool. I loved what the water did to the fabric, how it changed the shape of things, how the light in the pool detailed the patterns in the fragile garments. Then I enlarged the black-and-white images to 16 by 20 and hand-colored them with Marshall Oils. I called this my Gowned Series, and it ended up in several photography exhibits.

This love of water seemed to carry over into my film work. Pools, made with my mentor, Barbara Hammer, gave the viewer the experience of swimming in both the indoor and outdoor pools of the Hearst Castle. We filmed with an underwater housing. It seemed to be the first film in an ongoing obsession with this medium. Also, the water-themed films of Bill Viola blow me away.

Bud: You’ve fished in New Zealand and the Gulf Coast, but if you’re like most of us, fishing when we can, close to home is where the heart lies. What kind of water do you favor, and are you a trout person, or just a fisherperson? And what was fishing New Zealand like?

Barbara: I would say that I favor trout fishing, but I am open to almost any kind of fishing. I loved fishing for redfish in both Texas and Charleston because of the dropdead sunrises that go hand in hand with this kind of fishing. In Texas, I remember filming a flock of seagulls coming at our boat with a pod of redfish underneath them. My friend Jean was casting to them, and it was very exciting. The water was so special this time of the morning, as if it had been reserved just for us. I loved, loved fishing the South Island of New Zealand. Although you have to walk about half a mile between fish, the size of the fish is worth the walk. Also, I learned a lot about habitat and predators. Because there are so few overhead predators, you find the trout in places you would not expect, like in the middle of the stream on a sunny day. My favorite part of New Zealand was fishing in Wanaka in the tributaries that feed Lake Hawae and the Godley River near Fairlie. The gin-clear, glacial, blue-tinted water of these rivers was stunning. I have been fishing more in the past five years outside my home waters, partly out of curiosity and partly because I have found some other women, especially Fanny and my friend Diane Whitehouse, who like to travel as much as I do. I also love fishing in Argentina and Chile.

Bud: Stepping into the Stream both explains and invokes the attractions of fly fishing very effectively. Most of us need to do the same from time to time, but we’re not filmmakers. What advice would you give to the rest of us about how to communicate the attractions of the sport effectively with would-be’s and newbies?

Barbara: I am always trying to recruit more people, especially women, into this sport. What I usually do with women who are interested is talk to them about our club and direct them to our website: GWWF.org, so they can see what kinds of trips we offer and what we do. If they are interested in conservation, I direct them to Cindy Charles, our multitasking conservation chair. If they live outside of California, I tell them about our IWFF club and direct them to that Web site, www.intlwomenflyfishers.org, so they can locate clubs in their area. Our GWWF club also sponsors the Jo Clark Youth Fund, which offers Fishcamp scholarships for boys and girls 10 to 15 years of age, a fine resource for young people.

I had to learn fly fishing from scratch, but I found a wealth of classes in the Bay Area offered through local fly shops. Also, the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club always has members around the casting ponds who are more than willing to take some time to offer casting advice for anyone who needs it. I think the generosity and goodwill of the fly-fishing community is outstanding in general. Maybe it comes with the sport!

Bud: Here we are already at the obligatory Silly Tree Question: If you were a tree, what kind of a tree would you be?

Barbara: I would be a broad oak tree with children climbing on my branches and makeshift swings hanging from my strong limbs. I would adorn my coat of gold leaves in the fall, I would welcome mounds of snow around my trunk in the winter, and I would bow my outer branches to the wind.

To purchase a DVD of Stepping into the Stream, send a $25 check, payable to Barbara Klutinis, to Barbara Klutinis, 3935 Cesar Chavez St., San Francisco, CA 94131. The cost covers tax (where applicable) and shipping. Run time is 43 minutes, plus 30 minutes of additional features. To view the film’s trailer, go to stream.com/the_film.html.