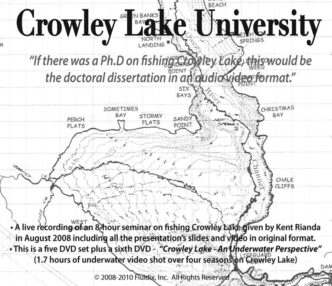

Crowley Lake University

Six-DVD set by Kent Rianda, 2008-2010; $79.95. Available online at thetroutfitter.com.

Lake Crowley (known colloquially as Crowley Lake) is a huge impoundment that was created when the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power dammed the Owens River in 1941 to provide a reliable supply of water for the growing Southern California metropolis. In so doing, the LADWP also created a phenomenal recreational trout fishery, consisting primarily of hatchery-raised trout, that now draws thousands of anglers each year on Opening Day, the last Saturday in April.

Crowley, moreover, has become a popular eastern Sierra destination for fly fishers. As Bill Sunderland notes in his angling guidebook Fly Fishing the Sierra Nevada, “Fishing Crowley is a must for every California angling enthusiast. Although it is a planted lake, the rate of growth is so fast that seven-inchers dumped in May will be fifteen inches long in October. And it is so big that many of the trout live for years to become five pounds or more.” Making the lake even more attractive for fly fishers is that from August 1 through November 15, only artificial lures with barbless hooks are allowed, and the five-fish daily bag limit drops to two, with a minimum size of 18 inches. This three-and-a-half-month period is known simply as “trophy season.”

As with fly fishing the surf, fly fishing a lake represents a significant challenge for the angler. The larger the lake, of course, the greater the uncertainty about where fish are to be found, and Crowley is big, with, according to one set of estimates, more than 8 square miles of surface area and 45 miles of shoreline. For the first-time visitor, if trout aren’t rising or otherwise visible, just where does one start? And, for the fly fisher who visits the lake irregularly (which is probably most of us), the issue becomes: What can one do to hook trout consistently throughout the angling season? Kent Rianda, owner of The Troutfitter fly shop in Mammoth Lakes, states that he has fished Crowley for more than two thousand days over nearly two decades, which clearly implies he has an enviable familiarity with the reservoir and its sportfishery. In August 2008, Rianda held a day-long seminar in Fullerton that he titled “Crowley Lake University,” noting “If there were a Ph.D. on fishing Crowley Lake, this would be the doctoral dissertation in a live format.” Subsequently, a recording of the seminar and its accompanying graphics were transferred to five DVDs, and a sixth DVD of underwater footage was added to create a set likewise titled Crowley Lake University, which is available from Rianda’s shop and other retailers in the eastern Sierra.

Each of the six DVDs in Crowley Lake University covers the details of one or two general, but related themes: “Trout Food and Where to Look for Fish,” “Tools to Find Fish and What Affects Fishing,” “Stillwater Nymphing (Midging) and Strike Indicators,” The “Lost Art of Stripping — Catch Bigger Fish!” “Underwater Video Analysis & Tying the ‘Optimidge,’” and “Crowley Lake — An Underwater Perspective.” (According to the packaging of the DVDs, these themes encompass 155 individual, specific topics.)

The presentation in the first five DVDs consists mostly of Rianda’s voice as he lectures, along with the graphics and video he uses to illustrate his points. You aren’t watching Rianda talk, you’re only listening to his voice while looking at supporting images. The analogy would be listening to a podcast while watching a PowerPoint presentation. The benefit of this approach is that it forces you to pay attention to what Rianda says. The downsides, for me, were both minor and infrequent. You’re unable to watch Rianda as he illustrates a point with his hands or other body English, as seems to occur during the discussion on how best to strike when a fish takes the fly (although his verbal explanations are sufficiently thorough as to help ensure you won’t become confused). Also, sometimes a single graphic is left on-screen for a long time while Rianda makes a number of points, as occurs when he discusses various stripping techniques. Again, though, if you listen, you learn.

As a lecturer, Rianda comes across as intelligent, articulate, and knowledgeable. Apparently he has worked as a science teacher, and this shows in the clarity of his instruction and in his experimental approach to learning how best to fish Crowley, where he employs, for example, “side-by-side” studies — in essence, fishing two rods at the same time that are rigged, say, with differing fly patterns. And he’s enough of a gentleman to give appropriate credit to others, such as Mike Peters and Harry Blackburn, who pioneered the successful use of indicators and nymphs at Crowley.

The sixth DVD in the set consists of underwater footage that has no narration (or even sound); its significance is discussed instead on the fifth DVD. What you usually see, though, are trout that seem to be consistently ignoring a small chironomid pupa imitation that’s hanging in the frame of the camera. It’s provocative video and leads viewers to a number of questions and hypotheses about the importance of dead drifting a fly in a lake’s current, the importance of tippet visibility, and the importance of the retrieve in stimulating a strike, among other issues.

Despite its rough edges, Crowley Lake University has real utility for fly fishers. First of all, I have no doubt that it will improve the average fly fisher’s ability to find, hook, and land trout at Crowley itself. The first DVD, in fact, discusses 19 specific fishing locations that are presented clockwise, from Crooked Creek to Alligator Point, and a number of these locations come up again in the other DVDs. Second, and of importance to anglers who fish elsewhere, is that the ideas Rianda provides are applicable to any trout lake that has a significant chironomid population, as Crowley does. I took 10 pages of notes while watching these DVDs, and points that I highlighted for my own angling include Rianda’s recommendations regarding prime trout temperatures, how to get the most out of fish finders, the pluses and minuses of different kinds of indicators, the importance of the right hook set, the importance of “the fly, not the guy” when nymphing, the importance of “the guy, not the fly” when stripping a streamer, the necessary details for a fish-attracting chironomid imitation, how to recognize subtle takes, how to nymph deep water, how to fish when the wind howls, how to calculate the depth of your fly based on the length and angle of your fly line (highschool geometry finally pays off!), rigs for targeting big fish, how to turn refusals into takes, etcetera, etcetera.

If you’re a novice at fly fishing lakes and chironomid hatches, Crowley Lake University will dramatically shorten your learning curve. If you’re an intermediate or expert lake angler, it will give you plenty of ideas to ponder and test.

Richard Anderson

Stillwater Presentation: A Fly Fisher’s Comprehensive Guide for Planning and Executing a Presentation System for Catching Stillwater Trout

By Denny Rickards. Published by Stillwater Productions, 2010; $39.95 hardbound.

In the DVD set reviewed above, Crowley Lake University, Kent Rianda places emphasis on fishing midge patterns under strike indicators. Denny Rickards, however, in his latest book, Stillwater Presentations, prefers other approaches, bluntly stating that “I’m probably the least qualified to write about presenting a fly [under an indicator]. . . . I don’t have the patience that this presentation requires . . . . I fish chironomids, but always with a pull-pause retrieve.”

Vive la difference!

Rickards, who lives in Fort Klamath, Oregon, has fished extensively across the West and has long been considered an expert fly fisher of lakes. Stillwater Presentations is his fourth book, and, according to Rickards, adds to the advice that he presented in one of his earlier works, Fly Fishing Stillwaters for Trophy Trout. (“That was chapter one,” he told me, when I asked how the two books relate to each other. “Stillwater Presentations is chapter two.”) It is a nicely-produced book, with glossy, heavy-stock paper, an abundance of well-composed color photographs, and text that’s easily readable by aging eyes such as mine. And Rickards is a good writer, getting his points across using short sentences and paragraphs that communicate without complexity or ambiguity. His prose flows so well that it’s easy to miss the fact that he packs a lot of information into this book’s 280 pages.

For Rickards, stillwater presentation “includes every element of fishing lakes from pre-trip preparations to setting the hook, choosing the right rod, line, leader and tippet selection, habitat identification, casting techniques, boat positioning, fly retrievals, fishing the proper depth and angle and presenting your fly so that it looks and moves as naturally as the natural food organisms found within a lake’s environment.” His purpose, therefore, is to help fly fishers develop “the skills to fish through variable changes with a variety of productive presentations. That means reducing our options to what works with less emphasis on a trial and error approach.”

There’s a lot to mull over in this book. With regard to the “variable changes” just mentioned, for example, Rickards explores the implications of weather for trout behavior, and he provides a nifty table that relates changes in barometric pressure to angling tactics. Although the target audience includes novice fly fishers — Rickards includes basic information, such as the meaning of various rise forms and how trout see, which are included in other how-to books — the bulk of his advice will be of value to fly fishers of all skill levels. As someone who has been fly fishing lakes for more than two decades, but never in any systematic manner, I found particularly interesting the sections that pertain to seasons, retrieves, presentations at different depths (“fishing the zones”), and presentations as they relate to various insect life-cycle stages.

I think it’s reasonable to say that lakes are more difficult to fish successfully than flowing waters. Stillwater Presentations is an important work for fly fishers who wish to understand the characteristics of these waters and their fisheries and to catch more and bigger trout. I think it’s also reasonable to say that as we age as fly fishers, we’ll likely find ourselves drawn more frequently to lakes. I know I’ll be referring back to this book over the years that come.

Richard Anderson