Better Flies Faster: 501 Fly-Tying Tips for All Skill Levels

By David Klausmeyer. Published by Headwater Books/Stackpole Books, 2001; $24.95 softbound.

In Mr. Natural Does the Dishes, an R. Crumb poster based on a comic from 1971, as Mr. Natural begins that task, he’s muttering “Gripe grumble” and “Mumble bitch gripe.” But then he gets into it, really gets into it, ends up whistling a tune, and after inspecting a gleaming glass, he declares, “Another job well done!”

Mr. Natural isn’t the only philosopher to notice that doing things well appeals to something deep in human nature. Not only do we take pleasure from a job well done, we take pleasure from contriving ways that enable us to do it with skill, ease, and success. That’s why how-to books strike a nerve, well beyond filling any immediate need to, you know, find out how to do something. And that’s why collections of tips on ideas and techniques for doing a job well — books like Dave Klausmeyer’s Better Flies Faster — can positively make that nerve tingle. We’re not Homo sapiens, the argument goes, not a species defined by wisdom (a proposition that any student of history could doubt), but Homo faber, a species defined by our desire to make things and by the techniques we develop to do so. The pleasure we feel in making things is of a piece with the pleasure we feel in contriving better ways to make them. It is one of the things that fulfills us.

One of the reasons why Rube Goldberg devices are funny is that they’re wildly ill-contrived means to simple ends. One of the reasons why Better Flies Faster is fun, if you tie flies or contemplate learning to do so, is that it’s full of ways to do a job well — or to do it better. Its appeal to what makes us who we are is hard to resist.

Dave Klausmeyer is the editor of Fly Tyer magazine and thus in touch with both the current state of the art and most of its prominent contemporary practitioners. For this book, in addition to having “swiped ideas from others when they weren’t looking,” as he puts it, he asked 84 other excellent fly tyers for tips on, yes, how to tie better flies faster. For the most part, the ideas aren’t attributed to a particular person, and like many good ideas, several of them have occurred to others seeking better means to a given end. (See, for instance, Andy Burk’s feature, “Improving Your FlyTying Productivity,” in this issue.)

Nor is Klausmeyer’s collection of tips targeted at a particular kind of tyer, and that’s one of the most important strengths of the book, along with its copious illustration with the author’s always lucid photographs. The subtitle promises fly-tying tips for all skill levels, but the book isn’t organized that way. It’s true that Better Flies Faster begins with a chapter called “Getting Started,” but even though that chapter does in fact contain some basic tips for beginning fly tyers, it also contains things that even intermediate and advanced tyers need to be reminded to do every time they sit down at the vise, or things they may not have thought of doing, or information they may not have known, including, for example, the number of hackles found on a Keough Tyer’s Grade cape, laboriously counted by A. K. Best. And it begins with “The First Rule of Fly Tying,” which I bet even expert tyers routinely violate: Wash your hands before you start tying. It prevents discoloring light-colored materials. (Washing them afterward isn’t a bad idea, either. Mom was right — you don’t know where that stuff has been.)

Likewise, the rest of the chapters — on materials, tools and tool tricks, dry flies, wet flies and nymphs, and big flies (streamers and saltwater flies) — contain plenty that a beginner needs to know, but also a whole lot that will provoke an “Aha!” from anyone who has been tying a while and who will recognize neat solutions to a host of problems, interesting suggestions for materials and sources, and a broad spectrum of clever contrivances for the easy and successful completion of many tasks that range from the routine to the frustrating.

In short, although many books aspire to providing something for everyone, precisely because this one is a collection of a lot of different particular ideas, it actually does. I thought I should give some representative examples of the promised tips for all skill levels, so when reading Better Flies Faster, as I took notes, I tried to distribute things that appealed to me into the categories “Beginner,” “Intermediate,” and

“Expert.” But those categories don’t really apply here, because the information is offered without any such categorical hierarchies. Its audience is Homo faber as fly tyer or would-be tyer, plain and simple. And what I put in each category turned out to be pretty arbitrary. I’m enough of an aging hippie to take fairly seriously the whole “Zen mind, beginner’s mind” thing, and I have no idea where the line between “intermediate” and “expert” is, although I sometimes find myself on the tyers’ side of the table at fly-fishing shows, which suggests I’ve conned someone into thinking I may have crossed it.

What I got instead of examples of what I thought others in the different skill levels would find interesting was a Rorschach ink-blot-test report on the particular kind of tyer I am — a list of basics that I need to recall more often, a list of things that struck me as good things to try to remember in the future for the specific kind of tying that I do, and a list of things that I absolutely want to try, because they’re solutions to problems that have been bugging me lately. Not only may your results vary, it’s certain that they will, because there is indeed something here for everyone who ties flies or aspires to do so, but what each reader sees will be what he or she most needs to see. As I said, that’s one of the book’s principal strengths.

One of the best answers to the question “Why tie your own flies?” is that it’s fun. It’s fun because we humans are the kind of critters who have fun making things and fun thinking up and using better ways to make them. Better Flies Faster will help anyone, of any skill level, get into it, really get into it, and be able to say, like Mr. Natural, “Another job well done!”

Bud Bynack

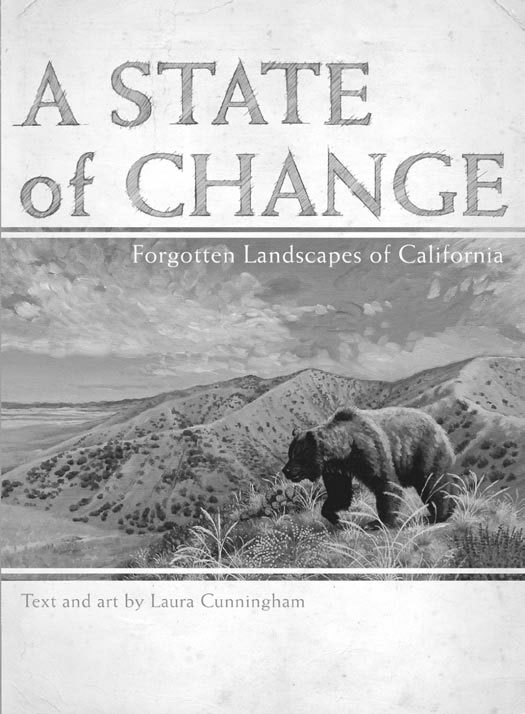

A State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California

By Laura Cunningham. Published by Heyday Publishing, 2010; $50.00 hardbound.

A State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California, Laura Cunningham’s monumental natural history, paints a vivid picture of California’s interrelated plant and animal communities before the arrival of the Europeans. Cunningham marshals evidence from an impressive range of sources and disciplines: the work of early painters, accounts from explorers, native peoples, pioneers, and naturalists, investigations of the remaining vestiges of semi-pristine landscapes, contemporary research in archeology, climatology, paleontology, and geology, and materials such as old photographs. With art from both her pen and her paintbrush, she offers a comprehensive look at what gave early California its reputation as one of the most abundant regions on earth.

Cunningham, who is both an artist and naturalist, has been traveling the state since 1980, seeking information to attempt a reconstruction of “the past world of Early California,” as she puts it. A State of Change reconstructs what an undisturbed nature looked like before the incursion of nonnative plants and animals — including most of us.

Anglers’ interests will likely focus on the chapters treating rivers, marshes, shorelines, and fish. Cunningham doesn’t mince words: Although some nearly ex-tinct animal communities, such as the condor and elk populations, have made comebacks, “our historic fisheries are on the verge of collapse,” she writes, Her examination of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River and Bay-Delta system and the coastal rivers, estuaries, and smaller tributaries gives us a hint of the magnitude of what we have lost.

What is important here is that she looks at all the interrelated ecological communities and shows how one act triggers others, in a ripple effect, across them. We get exhaustive dissertations on grasslands, oak savannahs, oak woodlands, forests, marshes, deserts, the dynamics of fire, and the plant and animal interactions that characterize these ecologies.

Over and over, we see how man-made changes in one element of the natural environment cause a cascade of consequences. Cunningham’s coverage of top predators and their relationships with grazing animals is a fascinating example. Grizzly bears were much more abundant than we realize. They lived in a world heavily populated with elks, deer, black bears, antelopes, and bison. The extinction of the California grizzly led to explosions in populations of ungulate grazing animals and subsequent overgrazing. This, combined with overgrazing by cattle and changes brought by invasive Mediterranean annual grasses, led to changes in runoff dynamics, erosion, and even water table levels that ultimately affected fisheries.

Her investigation of the role played by fire in undisturbed landscapes and humans’ relations with fire, from the Native American use of it in agriculture to the dynamics of our past and recent fire-suppression policies, also shows the consequences of human intervention in nature’s processes. In addition, it illuminates the dilemmas that we face as long as we live in wildland/urban interfaces.

I was trained as a field zoologist, and I appreciate the quarter-century of observational and deductive efforts that lie behind Cunningham’s reconstructive paintings and extensive analysis. This is an important book that should be in every library. The comprehensive nature of A State of Change and the vastness of its subject mean that it can be studied seriously as a textbook or left on the coffee table to be read, pondered, and enjoyed chapter by chapter.

Trent Pridemore