The Founding Flies: 43 American Masters, Their Patterns and Influences

By Mike Valla. Published by Headwater Books / Stackpole Books, 2013; $39.95 hardbound.

If you know anything about the history of American fly fishing, you’ll want to own this book. If you don’t know anything about the history of American fly fishing, you should own this book. And especially if you care at all about how we tie flies for American waters, this book should have a prominent position in your library.

That’s because for the first time, as far as I know, Mike Valla has brought together in one place an account of the major developments in the ways in which artificial flies were thought about, tied, and fished in the United States over the period from the mid-1880s to the late 1960s. The book covers what Valla calls the “archetypes . . . that eventually evolved into the contemporary fly styles we tie in our vises today and fish on our favorite waters,” told in terms of the contributions of “43 masters who helped make fly fishing and fly tying what they are today.”

Why 43? Well, “a book like this can be only so long,” and Valla’s criteria of selection were of necessity pragmatic. “Sometimes selection had to do with what information was available on a tier I would have loved to cover Syd Glasso, a classic West Coast tier,” he writes, “but it proved difficult to get my hands on enough good material concerning his flies and the development of his patterns.” And why the mid-1880s to the late 1960s? Because like any good historian, Valla deals with a time frame that provides sufficient critical distance to assess what has been truly important and what has endured. Someday there may be an organization called the Andy Burk Flyfishers to mirror the Theodore Gordon Flyfishers of New York, but not yet. . . .

The tyers covered, in the order he covers them, are Mary Orvis Marbury, Thaddeus Norris, Theodore Gordon, Reuben Cross, Walt and Winnie Dette, Harry and Elsie Darbee, Art Flick, Edward Ringwood Hewitt, John Atherton, John Alden Knight, Joe Messinger, Sr., Ray Bergman, Lee Wulff, Fran Betters, Eric Leiser, Elizabeth Greig, Helen Shaw, Lew Oatman, Keith Fulsher, Carrie Stevens, Joe Brooks, Don Gapen, Dave Whitlock, Art Winnie, Len Halladay, George Griffith, Jim Leisenring together with V. S. “Pete” Hidy, George Harvey, Vincent C. Marinaro, Chauncy K. Lively, Ed Shenk, Franz B. Pott, George F. Grant, Don Martinez, Wayne “Buz” Buszek, C. Jim Pray, Ernest H. “Polly” Rosborough, Ted Trueblood, Cal Bird, and André Puyans.

Who got included and who didn’t “had nothing to do with the volume of new patterns that a ‘classic’ fly tier created,” Valla writes. “Len Halladay was selected for the influence of only one pattern,” but it’s a doozy: the Adams. Griffith was included because of the Griffith’s Gnat, although Valla also tips his hat to Griffith’s contributions as a founder of Trout Unlimited.

The tilt toward the East Coast (and the upper Midwest) is evident in this list, and that’s inevitable, given the time frame involved. Also, as Valla makes clear, it reflects his own heritage as an angler and fly tyer. As a teenager who had read about fly fishing and was burning with the desire to fish the Beaverkill and Willowemoc, he got off a bus from his hometown of Binghamton, New York, in the trout town of Roscoe and was promptly taken under the protective wings of Walt and Winnie Dette, with whom he frequently stayed over the subsequent years and where he not only learned to tie flies from these iconic tyers, but met many others, which has allowed him to seed the book with interesting personal accounts and memories.

A review like this can be only so long, too, and I’m going to limit myself to mentioning what I found most striking about The Founding Flies. For starters, the amount of research that went into it is impressive. Some of this ground has been well covered before, especially the Catskill line from Theodore Gordon, whose life, or what we can know about it, has been closely scrutinized for some time, through Rube Cross, who was profiled as recently as the September/October 2013 issue of American Angler, to the Dettes, chronicled by Eric Leiser in The Dettes: A Catskill Legend, and the Darbees, chronicled by Harry himself with Mac Francis in Catskill Flytier — still a fun read, and you’ll find out how to skin a chicken. But more typical of what you’ll find is the sort of research based on the likes of issues of Pennsylvania Angler from the 1940s through the 1970s or “John McDonald’s now classic May 1946 Fortune article” that featured Elizabeth Grieg, along with tyers such as the Darbees and the Dettes.

And the inclusion of tyers such as Greig, whose simplified versions of classic wet flies appeared in the Noll Guide to Trout Flies and How to Tie Them, inspiring a generation of youngsters to become fly tyers, Mike Valla among them, is a revelation. I had not heard her name before. I had heard of Joe Messinger and the Messinger Frog, a bass pattern, thanks to Richard Alden Bean’s writings in this magazine, but I never appreciated the complexity or beauty of the pattern, and I never realized that it was Messenger who originated the Irresistible. Similarly, I’d heard of and tied Joe’s Hopper, but never had heard of its originator, Art Winnie, and of Lew Oatman’s streamers and Chauncy Lively’s efforts at producing weighted streamers — proto-Zonkers — I was equally ignorant. However much you know about the history of American fly tying, I can pretty much guarantee that your own blind spots will be illuminated somewhere between the covers of The Founding Flies.

Another revelation is to be found in the extensive picture spreads of flies either tied by the featured tyers themselves, which are taken from museums or personal collections, or tied by Valla or by others who have devoted themselves to learning and perpetuating classic tying styles. While it’s nice to see a Quill Gordon tied by Theodore Gordon, what really is enlightening are the examples of techniques that, at best, one has only read about. For example, I knew that Vince Marinaro advocated tying mayflies with splayed hackles in the thorax — the opposite of the tight, up-and-down Catskill style of hackling — but I didn’t really know what that meant and how radically splayed they were until I saw the photos of mayfly imitations he’d tied. And I didn’t know that Marinaro believed you actually don’t need to imitate the abdomen on a mayfly at all — that at least on the placid waters he fished, all you need is a thorax that floats well and that keeps the tails elevated out of the water, the way the naturals ride the currents. Wow — that’s rad.

This being a history of “archetypal” flies and their creators, Valla can’t avoid the tricky and often explosively vexed issue of who created what, when. And he doesn’t. The book is unflinchingly full of origin stories, from the space for the Turle Knot behind the eye of Rube Cross’s classic Catskill ties, to the origins of Art Flick’s use of urine-stained fox fur for the bodies of Hendricksons, to Carrie Stevens’s creation of the Gray Ghost streamer, to Don Gapen’s creation of the Muddler Minnow as a “cockatush” imitation — a sculpin — on the banks of the Nipigon River, to the multiple accounts of the origins of the Adams, and beyond. Where there are differing claims to the creation of a pattern, he says so and presents them, but when he has solid evidence for the origin of one of these archetypal patterns, he stands by it.

What is more interesting, however, is not his effort to account for origins, but the way he traces influences — from Messinger and his Irresistible to Harry Darbee’s deer-hair-bodied Rat-Faced McDougall, for example, or ways in which the Dettes may have learned tying tips from Roy Steenrod, in addition to having reverse-engineered Rube Cross’s flies when he refused to communicate his tying secrets, or the way in which Art Winnie’s grasshopper imitation morphed into Dave’s Hopper in the vise of Dave Whitlock. And those traces of influence continue in the work of the many present-day tyers whose enthusiasm for and research on these patterns he quotes and whose work frequently appears in the picture spreads.

The flip side of these origin stories is the attention that Valla devotes to the other flies that these tyers also tied — flies other than the ones for which they are known. From Theodore Gordon’s multiple versions of his Bumblepuppy streamer, to Harry Darbee’s Two-Feather Fly, to the steelhead flies of John Atherton, who was otherwise known for the theories of mayfly imitation embodied in his patterns, to Lee Wulff’s molded plastic Form-ALure flies, which never caught on, to the different colors other than gray in which the original Adams was tied, to Jim Pray’s steelhead flies other than the Optic series, to the other patterns tied by Cal Bird in addition to his Stonefly and Bird’s Nest, the versatility, inventiveness, and artistry of these tyers is clear. They weren’t just creative tyers. Most of them were also good all-around technicians.

Although the story that Valla has to tell begins in the 1880s in the East and ends in the late 1960s in the West, the organization of the book isn’t simply chronology mapped over geography. From chapter to chapter, there are basic themes that give the book an underlying architecture — and it’s not a list of forty-three different topics, either. Thus, an account of “the early birth of American fly-tying creativity” in the chapters on Mary Orvis Marbury and Thaddeus Norris leads to an exploration of the rise and development of the Catskill style of fly-tying in the work of Gordon, Cross, the Dettes, the Darbees, Art Flick, E. R. Hewitt, John Atherton, and John Alden Knight, then to cross-influences between tyers and a broadening of geographical focus with the work of Joe Messinger, Sr., Ray Bergman, Lee Wulff, Fran Betters, Eric Leiser, and Elizabeth Greig. What follows that is in effect a history of the American streamer fly as tied by Helen Shaw, Lew Oatman, Keith Fulsher, Carrie Stevens, Joe Brooks, and Don Gapen, followed by a history of the grasshopper imitation in the works of Dave Whitlock and Art Winnie. In the process, the scene shifts to the Midwest, with the account of Len Halladay’s Adams and the Griffith’s Gnat, then to Pennsylvania for Leisenring’s and Hidy’s flymphs, George Harvey’s patterns and teaching at Penn State, and the flies of Vince Marinaro, Chauncy Lively, and Ed Shenk. With a trip through Montana that looks at Franz Pott’s woven flies and what George Grant did with the woven-fly technique, we finally make it to the West Coast with Don Martinez’s adaptations of Catskill traditional ties to Western conditions, in addition to his development of the Woolly Worm, then Buz Buszek’s innovations, especially for caddisfly imitations, in contrast with the mayfly-centric Eastern tying traditions, Jim Pray’s steelhead flies, and, with Polly Rosborough, Ted Trueblood, Cal Bird, and Andy Puyans, what amounts to a brief history of nymph patterns in America, with a backward glance at eastern predecessors in the nymphs of Hewitt and John Alden Knight. Maintaining that kind of structure in “a book like this,” which ostensibly deals with a large number of often very different people and conceptions of fly tying and fly fishing, is no small feat.

Although these were all creative tyers, some of them, at least, won their presence in this august company in part because they were also great teachers of fly tying — George Harvey is one, and Andy Puyans is another. On top of that, some were popularizers of their own and others’ flies. That’s particularly true of Ray Bergman, but also of many other tyers whose work became known either because they wrote about it themselves in books or magazine articles — the tradition begins with Mary Orvis Marbury herself and Theodore Gordon — or because other people wrote about them and their flies or featured them in catalogues, as Dan Bailey did for his version of Gapen’s Muddler. A fly doesn’t become an archetypal classic if nobody knows about it.

One result of the relationship between influence and popularization is that if you want to assemble a library of classic American fly-tying literature, the bibliography at the end of The Founding Flies is a great place to start. And of course, no red-blooded fly tyer could read this assemblage of classic patterns, some of them now forgotten, and not want to sit down at the vise and bend some feathers. Valla has thoughtfully provided a “Selected Dressings” section, so if you find yourself yearning to tie some version of Gordon’s Bumblepuppy — I have a friend who swears by them — or Lew Oatman’s Brook Trout, or Jim Pray’s Red Optic, between the wonderful photographs and the dressing recipes, you can go for it.

These are just a few of the reflections that a reading of The Founding Flies prompts. Mike Valla’s previous book, Tying Catskill-Style Dry Flies, established him as a historian of one major American angling tradition. In its scope and depth, The Founding Flies stakes a broader claim for Valla as one of the country’s leading historians of the art and craft of the artificial fly.

Bud Bynack

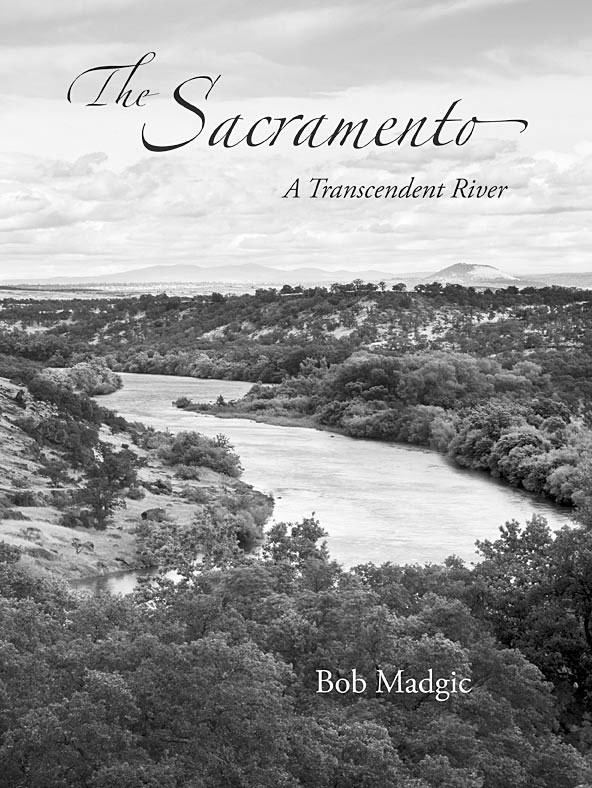

The Sacramento: A Transcendent River

By Bob Madgic. Published by River Bend Books, 2013; $24.95, softbound.

Every story has a shape, and most turn on some kind of reversal or conflict. The broad outlines of the story of the Sacramento River, should already be familiar to every Californian, a state where, as Mark Twain is supposed to have said about the West, “whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting over.” You don’t need to fish the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta to be aware that degradation is a central part of the river’s history.

But degradation is not all there is to the story that Bob Madgic tells in The Sacramento: A Transcendent River. It is a story not of decline and descent, but of descent and return, an account of the ways in which the resources of the river, material and spiritual, natural and human, national and personal, endure and can prevail.

Madgic begins with the natural history of the river — its geology and ecology — but then the story shifts to the relationship between the river and the human inhabitants of the land around it. That starts with “River as Community,” an account of the Native Americans who inhabited the Sacramento Valley prior to the arrival of white adventurers, farmers, and miners.

This is no mere gesture toward a romanticized past of lost harmony with nature. Prior to his retirement, Madgic’s work as an educator focused on American history (See the interview with him in “California Confluences” in this issue), and Madgic writes with a historian’s rigor and attention to detail about every aspect of the river’s past. Here, there are necessarily brief, but detailed accounts of the relationship between the river and the daily lives of the Wintu, Winnemen Wintu, Nomlaki, Patwin, and Maidu peoples who lived along the river, from its sources downstream.

The chapter that follows, “The River as Resource,” covers the arrival of white settlers, beginning with Gabriel Moraga in 1808, in what was still New Spain. It covers the origin of Sacramento as a town, the history of mining, the rise of agriculture, the conflicts between miners and farmers, the development of flood-control infrastructure as the white population of the area grew, and the increasing use of the river for the transportation of people and goods. There’s also a chapter on the development of the upper river as a railroad corridor, tourist destination where urbanites could “take the waters,” and angling venue. Here and throughout, copious photos and maps support and illuminate the account.

Then Madgic tells the familiar story of the river’s degradation in terms of the rise of the water projects, diverting its flows south, and the decline of the Delta and of the salmon runs. Any angler is familiar with the broad

outlines of this tale, but the devil, as always, is in the details, and it’s the detailed and balanced account of details, both here, in an account of the building of Shasta Dam, for example, and throughout, that makes the book so valuable.

And while the devil is in the details, there are angels to be found there, too. The final chapters of The Sacramento detail the rise of conservation efforts — successful conservation effort — in the past and in the present, focusing on the work of specific individuals and organizations such as The Nature Conservancy and John Mertz of the Sacramento River Preservation Trust, to name just two. As a result of the efforts of so many, the soul-restoring benefits of the river have been brought back into better balance with the more pragmatic economic uses of the river. Today, it is both a recreational resource and an educational resource, teaching future generations about the value of the natural environment

Not only does every story have a shape, but most have some kind of message. As Madgic notes in an epilogue, and as we all know, “the issues impacting the Sacramento River persist.” The story that Madgic has shaped here ends on an upward trajectory. He’s told the tale of how human efforts have led not just to the degradation of the river’s natural resources, but to their recovery — the way in which those necessary efforts have resulted in real improvements in the balance between the many uses of the Sacramento River, from the irrigation of crops to the renewal of the human spirit. In a sense, then, what Madgic has written is actually a how-to book: how to have hope for the future of conservation efforts in California and beyond and how to make those hopes come true.

Bud Bynack