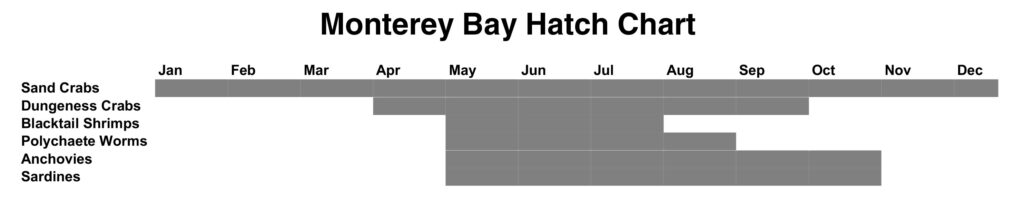

Any good trout fisher knows that a working knowledge of insect hatches will lead to better angling. Through careful observation and intelligent fly selection, top-notch fly fishers are able to determine quickly which fly to tie to their tippet and how to fish it properly. The same holds true in the surf. While the likelihood of surf-zone fish feeding on actual insects is pretty low, there are “hatches” of other foods that surf-zone fish key on. Knowing the what, when, and where of fly selection in the Monterey Bay surf and how to fish that fly is every bit as important as it is in fresh water. I have lost count of the number of times I have seen folks fruitlessly flailing with the wrong fly while another angler fishing just a few feet away got strikes on almost every cast. Knowledge is power.

Sand Crabs: The Year-Round Hatch

The staple food for most Monterey Bay surf-zone fish is the sand crab. These one-to-two-inch-long crustaceans live in the top few inches of sand and provide a reliable source of food for fish, shorebirds, and sea otters all year long. In the spring and summer months, sand crabs form dense colonies just beyond the water’s edge. These crab beds will typically cover 300 to 500 square feet. Occasionally, you will come across megabeds that are over 10 feet wide and measure 100 feet or more from end to end. When you consider that a healthy bed can contain as much as two pounds of crab per square foot, the amount of food available to fish and other creatures is astounding. A megabed can hold over two thousand pounds of crabs! It’s no wonder that surf-zone fish focus on these all-you-can-eat seafood buffets.

As you walk through the suds, you will notice that sometimes your footing goes from firm to soft. It’s as if you had just stepped into quicksand. If you are wearing polarized glasses, you will see that the sand appears to be bubbling and boiling. You have just stepped into a sand crab bed that is shifting with the tide. Look closely, and you will see sand crabs exiting the sand and scurrying a few feet before quickly reburying themselves. This short migration occurs throughout the day and enables the sand crabs to stay in the shallow swash zone, where they find a steady supply of food particles.

As you might imagine, when sand crabs exit the sand, they are very vulnerable. Surf-zone fish know this, and during low-light conditions will often move into very skinny water for an easy meal. To take advantage of this phenomenon, I get to the beach before sunrise. The reason for the early start is that sunshine typically drives fish out of the shallows. Before I step into the water, I flick a few casts into the swash zone. Often, I will get quick, tapping hits from perch or smelt. Occasionally, something a lot larger latches onto my fly. It’s amazing how a yard-long leopard shark or striper can feed un-detected in such skinny water.

When you hook a large fish in the shallows, it will quickly exit the scene. This usually involves an initial explosion of water, followed by a screaming run through the breakers. I promise you, this is every bit as exciting as hooking a bonefish on a tropical flat.

Don’t pass up a piece of water just because someone has already fished the spot. On many occasions, I have arrived at the beach at an ungodly hour only to discover die-hard conventional-tackle anglers already working the water. These apparently nocturnal beings usually fish giant top-water plugs or massive plastic baits. For some reason, they often ignore the shallow swash zone. I wait for them to move down the beach, slip in quietly behind them, and work the shallows. You should see the look on their faces when they hear the fly reel screaming.

During winter, the percussive energy of larger waves usually drives the sand crab colonies farther offshore. This is when you need to fish the offshore bars and troughs. Even at low tide, you often need casts of 70 feet or more to reach the beds. Marginal casters tend to struggle in the winter, because they simply can’t place their fly where the fish are feeding — yet another reason to practice your casting.

Sand crab fly patterns range from almost perfect copies of the real thing to creations that are unlike any known DNA-based life form. While I can appreciate the thought and skill that goes into lifelike sand crab patterns, I no longer bother tying such works of art. Three factors are critical to the success of sand crab patterns: size, color, and weight. My go-to pattern most of the time is a light tan Kwan. This fly was originally tied to mimic toadfish in Florida, but works equally as well as a sand crab imitation. This pattern sinks quickly when tied on a size 2 hook with bead-chain or lead eyes. It is best to attach the Kwan to your leader with a loop knot, which helps it move with a sand-bumping action that is similar to the way sand crabs move when scurrying for cover.

Don’t overlook the use of orange materials in your sand crab patterns. During the spring and summer, female sand crabs carry large masses of highly nutritious bright-orange roe. Fish key in on this color in a big way. In fact, you can have a lot of success by just fishing an orange Glo Bug pattern.

Before we leave the sand crab, I need to provide a word of caution for anyone who eats surfzone fish. Over the past few years, I have been working with researchers in the rapidly evolving field of cyanotoxins. These very potent toxins (some are more lethal than cobra venom) are produced by cyanobacteria, a 3.8-billion-year-old life form. The bad news is that cyanobacteria are becoming more common as our waterways receive extra nutrients from agricultural and urban sources. The death of 21 or more sea otters in and around Monterey Bay has been linked to these toxins. These animals took several days to die an agonizing death as a toxin called microcystin melted their internal organs. I saw the necropsy shots; they were very disturbing. The primary food source for a number of these unfortunate animals was sand crabs. The sand crabs must have picked up the toxins when they filtered cyanobacteria from the water. In addition to cyanotoxins, the bay seems to have had a steady increase in red tides over the past few years. Most people know not to consume shellfish such as mussels or clams during red tides, since they can accumulate the paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins produced by red tide organisms. However, few people consider the possibility that these toxins may also be in the fish they catch. I spoke to one local angler who also walks his dogs along the beach. He told me that one of his dogs had multiple seizures after eating sand crab roe. It took three weeks for the dog to recover.

These dramatic examples may be the tip of the iceberg. Researchers are starting to find evidence that continued exposure to even low levels of cyanotoxins may have long-term health effects. So while there are no specific data at this time that show that consuming surf-zone fish is a health threat, I feel it makes sense to think twice before taking these fish home for dinner. Believe me, I am not a catch-and-release Nazi. I simply won’t eat anything that eats sand crabs anymore.

Polychaete Worms

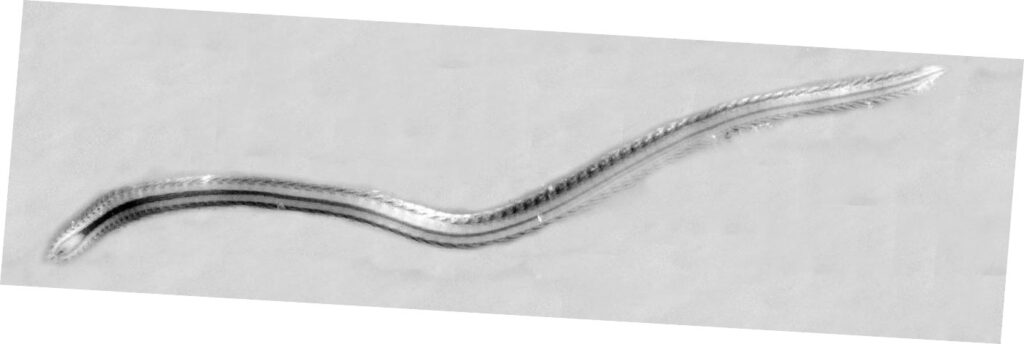

While not as common as sand crabs, polychaete worms provide a regular supply of easily digestible fat and protein for surf zone fish. Think of them as surf-zone string cheese .There are a number of species of polychaetes that inhabit the Monterey Bay sands, though most are pretty small. The most common is Nephtys californiensis, also known as the Shimmy Worm. This squirmy creature inhabits the top few inches of sand and typically ranges from one to six inches long. Densities of 5 to 10 worms per square yard of sand are normal. Over the years, I have conducted many sampling sessions on the bay’s sandy beaches, trying to figure out where the worms congregate. Scientific literature suggests these worms prefer well-sorted sands with a specific range of grain sizes. That’s useful information for a field biologist, but of limited value to someone waving a fly rod on the edge of the Pacific. I have found they seem to prefer to hang out just below the midtide line, though I occasionally find them farther up the beach.

This information is important. It means you should expect worms to become more easily available to predators around midtide, when breaking waves are pounding their habitat and flushing them out of the sand. Once evicted from the sand, these worms swim with a rapid, snakelike motion. With their iridescent skin, they resemble a wiggling piece of faded Flashabou. Fish will stack up behind breaking waves and dash in to nail the shimmying worms. These fish are usually suckers for a quick-sinking fly tied with Flashabou or another flashy material. For really hot action, you need to drop your fly right behind a wave that has just broken. This takes some timing and coordination, but is well worth the effort. Fish will also hold on the edge of troughs, cuts, and rips, waiting for fast-moving currents to carry struggling victims toward their hungry jaws.

In addition to this daily delivery of string cheese, nights from June through August provide even more chances for fish to feed on errant polychaetes. This is when the worms leave the sand to swim and spawn. If you get to the beach before the crack of dawn, you may be lucky enough to see the nuptial dance up close. I have seen it a couple of times. The worms gyrate in the water with seemingly spastic motions as they shed eggs and sperm. Needless to say, few fish will pass up a totally defenseless worm. Under these circumstances, a slinky fly that drops slowly through the water is a killing pattern. The closest I have come to mimicking this motion is with my P.O.S pattern (For more on Rob Ketley’s saltwater fly preferences, see “Surf Flies” in the January/February 2008 issue of California Fly Fisher.) It does not look much like a worm in the vise, but when twitched through the water, it moves seductively and gives off flashes of iridescence, just like the real thing. Jay Murakoshi’s 10-40, with its rubber tail, is another great worm pattern.

Dungeness Crabs

Dungeness crab populations are tied to a phenomenon called the “spring transition,” when the California Current drives planktonic crab larvae onto the continental shelf. When the transition is early, we get more crabs. When it is late, we get fewer. In recent years, the California Current conditions have been very favorable, which has resulted in plenty of juvenile crabs on the bay’s sandy beaches. In fact, several beaches have seemed to have more immature Dungeness crabs than sand crabs. Needless to say, the fish do not pass up this food source. Stripers that move into the surf to load up on sweet crab meat are usually more than willing to take a crab pattern. I have found the best technique is to locate a strong rip and fish the edge of it with a Merkin or other crab imitation on a fast-sinking line.

Shrimp

Blacktail shrimp are often found feeding just behind the sand crab beds. Though the shrimp are not particularly numerous, fish seldom pass up shrimp meat. Bait anglers know this and often load up with limits of quality fish by using grass shrimp on their hooks. For fly fishers, shrimp patterns such as tan-colored Crazy Charlies fished on fast-sinking lines are a great match for the hatch. If the sand crab action seems slow, switch to a shrimp pattern and work it with quick, six-inch strips. You may hit pay dirt.

Sardines and Anchovies

Last year, the stripers that were landed in Monterey Bay were surprisingly muscular. The fish had big shoulders, and many resembled elongated footballs. This extra muscle was reflected in their fighting capabilities. I still vividly recall one particular fish that tore off over 300 feet of line and backing in a pell-mell dash for deep water. I was blown away when, 20 minutes later, I finally scooted a modest 10-pounder onto damp sand. Plenty of other fish had me well into the backing last year, too.

The most likely reason for this extra bulk and power was the presence of large schools of sardines. From May through September, sardines ranging from 4-inch firecrackers to 10-inch adults could be found from Monterey to Santa Cruz. Many local boat anglers capitalized on this abundance by fly-lining live sardines right into the surf. On New Brighton Beach, at the north end of the bay, a string of boats was lined up not a hundred feet offshore for weeks on end. I saw some big stripers and even white seabass hooked just feet from dry sand. Fly fishers who worked larger baitfish-style patterns along this beach were rewarded with hits from very fit fish. I did very well with a 6-inch chartreuse-over-white Deceiver pattern fished on an intermediate line. On less sheltered beaches, rips provided the most consistent action, though I caught fish in the troughs regularly enough. On several occasions, the top-water bite was wide open. For me, this is the cream of the sport. Foggy morning hours provided multiple blowups on large (8-inch-long) Crease Flies fished behind a floating Scandi head. The fish were so charged up, they often missed the fly or threw it in a spray of water a foot or so into the air. While top-water fishing is not as successful as subsurface fishing in the surf zone, the excitement factor more than makes up for the rather modest hookup rate. While sardines provide a big chunk of food, the bay is more commonly home to schools of anchovies. Ranging from small, two-inch pinheads to the mature six-inch adults, anchovies will often move in very close to shore to feed on plankton. They are seldom left unmolested. Terns, grebes, sea lions, dolphins, and porpoises, along with stripers, white seabass, and mackerel all move in close to load up on these oil-rich fish. A white or chartreuse-overwhite Deceiver style pattern usually works wonders when the anchovies are in.

Halibut love anchovies, too. When I know halibut are in the surf, I head to the bay’s sheltered beaches with my indicator Clousering rig. This setup requires a floating line with a very buoyant indicator and a 1/0 Clouser loop-knotted to the business end of a 10-to-12-foot leader. The indicator is primarily used to impart a jigging action to the fly, which is deadly on halibut. This setup can be a handful to cast. I have found the rig is a lot easier to manage by using a medium or large Thingamabobber. The light weight and superb buoyancy of this particular indicator make casting the rig a lot easier.

Sometimes, the anchovy action can get insane. Back in the late spring of 2005, a massive school of anchovies was held against Sunset Beach by marauding bands of dolphins and sea lions. Looking down from the cliff top, the school was visible as a dark purple band that stretched for hundreds of yards along the beach. Occasionally, the band would split in two as a large predator tore into it. Almost hyperventilating, I ran down to the water and waded in. I figured that if I could get my fly beyond the mass of anchovies, I might pick up a striper or halibut.

It was not to be. I waded in as deep as I dared, but the school was too large. I simply could not get my fly out beyond it. After each cast, I would make a few pulls on the line and foul hook an anchovy. On several occasions, I found myself completely surrounded by thousands of fish. The action of their tails sent vibrations through my waders. It was like standing waist deep in a room of purring cats. Eventually, I gave up and walked up onto the dry sand. The gulls were so full of anchovies they did not even bother to fly away. Surrounded by dozens of fat, happy gulls, I sat down and enjoyed the spectacle.

Monterey Bay is an incredibly productive place. But unless you are fishing the right fly in the right way, it can also be an incredibly frustrating place. Take the time to figure out the “hatch,” and you could end up enjoying some of the most exhilarating fishing in the state.