There are some things you never forget — not the feel, the sight, or the scent. I caught my first steelhead on the Garcia River, and the moment is tattooed on my being. So many aspects of that January Sunday nearly two decades ago were pure magic — the redwoods, the crisp air, the uniquely green flow and deep blue sky, the intimate solitude, the ferocity of the fish, and the charge of emotions and sensations I experienced over the course of several hours. My life before and after that day — hinging on that 15-minute encounter — is two separate stories. To say that pretty little river on the Mendocino coast and its wild steelhead are important to me would be a gross understatement.

For the remainder of that winter steelhead season, I fished the Garcia as often as I could, which was practically every week, well into April. There were no seasonal closures then, and I fished until the run appeared to be over. At first, I returned only to the pools that had given me fish on that first day. Eventually, when flows allowed, I began walking the river from the upper fishing boundary to Highway 1. I followed the same devoted routine for a couple of years. My wife assumed I had a mistress named Garcia.

Never mind that I wasn’t fly fishing; the method employed isn’t critical to the point I want to make. However, it does play a role. I abandoned the use of bait after the first couple of trips and the following year began to fish the river with spinners assembled from purchased components. On a willow-choked river such as the Garcia, spinning lures can be highly effective in attracting and moving steelhead from places unreachable with other methods. Let’s just say, I caught plenty of steelhead, and the few friends who fished with me in the same way did, as well.

For those couple of years, often walking long reaches of the river each day, it seemed fish were everywhere. When the water was low enough to allow easy crossing, it was generally clear enough to see into all but the deepest holes. And often, while wading a shallow glide, walking downstream midchannel, I would cross paths with steelhead moving upriver, gray, stately ghosts hovering over the stones, silently slipping by in pods of four or five, sometimes a dozen. I’d see them holding in pairs or small groupings in deeper slots under hanging alder branches. While I was always elated to spot the fish, and each incident added meaning and intensity to the day, I began to take it for granted they would be there every visit. Dependably, those first couple of seasons, they were.

Eventually, the attraction to fly fishing was too strong for me to resist. I loved the lore. I loved the literature. I loved the flies. After a couple of seasons pitching metal, I stashed the spinning and casting rods and went at it, fortified with an assortment of books, videos, and a new kit of bargain fly gear. My catch rate, of course, plummeted. I fully expected that to happen and didn’t panic. I didn’t relapse to the deadly flashing, whirling lures. I stuck with it and took my lumps.

In hindsight, I see the errors: I mostly fished water ill-suited for the way I was fishing and for what I was fishing. I knew where steelhead should be, and I tried to get my overdressed, underweighted flies to them on a sink-tip line more appropriate for swinging a broad Deschutes tailout at prime flows. Most of the upper river lies were difficult spots to sink and hold a fly — trenches against a high bank, slots under the willows, deep holes tunneled with branches. I wanted to get my steelhead on a tight-line swing, and the way I was going about it wasn’t working. I was not getting my flies into the zone. I needed to edit my water, or I needed to go down to the estuary and join the lineup of whizzing shooting heads and beaded Comets. I suppose I could have joined the Minor Hole gang, but it didn’t fit my ideal, the one that had been so indelibly formed that first day and by that first fish.

Aside from my own ineptitude, I noticed something else about my days on the river. After my conversion to fly fishing I wasn’t able to allot as many days each winter to visiting the river, but when I did go, when I walked from, say, Buckridge to Windy Hollow, crossing, looking here and there, I wasn’t seeing fish in the places I expected to see them. In fact, I wasn’t seeing them at all. Friends using conventional tackle were getting a few fish here and there, and I’d occasionally read a good report, but by and large, it seemed the fish had gone missing. At first, I didn’t really focus on it; after all, my own unpolished fishing was no indicator of how many fish might be around. But after a couple of seasons, it seemed clear the period of relative abundance I had the privilege of witnessing in the first half of the 1990s was waning. My attention turned to other Northern California rivers and even more so to far-off destinations, particularly in British Columbia. My love for and interest in steelhead and steelhead fly fishing continued, developed, and grew even deeper. In the interim between my Garcia River days and today, fortune has smiled on me. Certainly not monetarily — there’s no money in this gambit — but in such a way that I’ve had opportunities to quench my fishing thirst, at least in part. I’ve been lucky to build a life around sea-run fish, in particular, steelhead. And I’m grateful to the Garcia River. I miss it. I miss our time together. I’ve moved on, but I’m not fully comfortable that I have. Perhaps I owe something in return.

But, if I do, my gratitude is not what’s important. What I’ve done is not important. I’ve laid down this brief history not because it props me up — in fact, consider my story as something that could happen to anyone — but because it illustrates the power and value of the unexpected wilderness experience and, in particular, the significance and presence of the elements that make up that experience. How critical are the health of these things to the health of the human spirit? How do they drive imagination and enliven our culture? How much a part of us are these intangible things? I’m hoping this minor tale might provide a perspective for thinking about the future of the Garcia River and its neighboring streams. To me, they are so important in defining what Northern California is, what it means. Like so many, I came here as an outsider, seeking some elusive something, a reinvention. I came looking, and these rivers and trees, these inspirational fish, this soulful coastline, became an integral part of who I am.

People like me will come and go, but rivers such as the Garcia will keep on doing what they do. They’ll keep draining water to the sea and providing opportunities for life. As long as they are left to flow clean and healthy, they will facilitate everything that is bright and true about existence. The big question — and what is important — of course, is what our role will be in that continuum. What is in the near future for the Garcia and rivers like it in Northern California?

Recently, I’ve heard stirrings of change on the Mendocino coast. As it turns out, the Garcia River has no shortage of friends, and it has received no shortage of attention at the federal level. A little backstory: in planning by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the river has been identified as a high-priority watershed for the recovery of federal Endangered Species Act–listed Central California Coast coho and California coastal chinook salmon, as well as for Northern California steelhead. Since the late 1980s, in excess of 25 million dollars has been devoted to conservation and rehabilitation efforts in the watershed — for riparian restoration, stream-channel wood input, and erosion-control road projects. One million dollars has gone into monitoring the recovery progress. Good intentions have been showered on the Garcia River. What could go wrong?

Within 15 years of the first efforts, the river’s steelhead population showed marked and encouraging signs of recovery. In the 2000s, after the down period I noted, prospects for the river’s steelhead were beginning to improve. Today, the habitat report is positive, and juvenile steelhead surveys indicate their population’s health should be reasonably good. But something is amiss. Recovery seems to have stalled. Adult steelhead numbers are not corresponding to the perceived health of the watershed.

Apparently there is an 800-pound gorilla in the house. The Garcia’s lagging recovery may be accountable in large part by the age-old nemesis of honest, law-abiding anglers everywhere: poaching. To find out more, I talked with Joshua Fuller, a fisheries biologist at NMFS.

“Spear fishing, prohibited netting, and snagging with barbed and weighted hooks have become familiar fishing practices on the Garcia in recent years,” explained Josh. “The term ‘poaching’ describes these activities, but it doesn’t do justice to the severity of the problem. At stake are decades of conservation work and the future of the river’s endangered and threatened salmon and steelhead runs. Over 25 million dollars in government and private funding has been invested in the restoration of the watershed, and in the early 2000s, the investment started to yield strong returns. As the numbers increased, however, so, too, did the impact of poaching. Fish returns on the Garcia have recently declined, even as numbers have seemed to increase in adjacent watersheds.”

Fingers have been pointed at poaching incidents on tribal lands — the river flows through two tracts of land owned by the Manchester–Point Arena Band of Pomo Indians, where jurisdictional issues make enforcement difficult — as well as at other poaching incidents throughout the watershed. Well-documented is the case of Kyle Stornetta: in the course of investigating drug-related activity in March 2012, 18 wild steelhead were seized by California Department of Fish and Wildlife wardens from his freezer. It seems blame should not be placed on any one set of shoulders, literally or figuratively.

As I understand from Josh, at the time of this writing, there are developing efforts aimed at improving coordination among federal, state, local, and tribal officials with the goal of eliminating poaching on the Garcia River. Along with the Pomo band and federal and state agencies, Congressman Jared Huffman lent his leverage to broker a potential resolution. Also at the table are Trout Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy, and The Conservation Fund. Three aspects of the issue and effort are worth highlighting at this point.

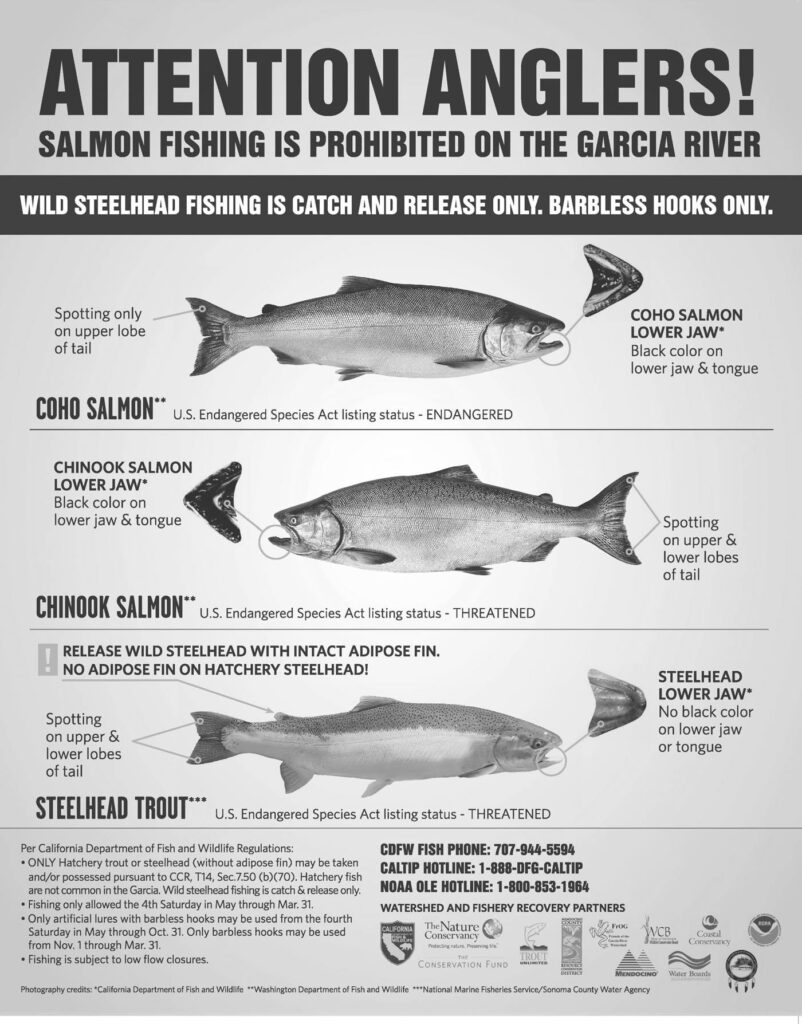

First, a project is underway to post signs at access points on the Garcia reminding anglers that salmon fishing on the river is illegal and that steelhead fishing is catch-and-release only, with single barbless hooks. The signs also include clear species identification instructions, along with phone numbers to use in reporting violators. This is a needed first step, and ongoing efforts will be required to keep signs clearly posted.

Second, concerned local citizens have initiated a reward program to encourage reporting of offenders: $1,500 is offered for information leading to the conviction of anyone illegally taking (poaching) salmon or steelhead from the Garcia River or from any of its tributaries. Those with information are encouraged to call CALTIP’s anonymous 24-hour hotline at (888) 334-2258 or the NOAA Office of Law Enforcement hotline at (800) 853-1964. With funding for enforcement running low, anglers may be the first line of defense. Needless to say, all who visit the river need to be vigilant.

Third, a regulation change has been proposed that would redefine the data source for the low-flow angling closure trigger for Central Coast streams, including the Gualala, Garcia, and Navarro, from flows at the Russian River Guerneville gauge to those at a gauge more relevant and representative of conditions on the Central Coast streams. The Russian River drains a significantly larger watershed, and its flows are artificially regulated by dam releases. Using its data to regulate angling openings on the smaller, free-flowing Central Coast streams makes little sense. In extended dry periods, the Russian can and frequently does exceed 500 cubic feet per second at Guerneville, the trigger for opening Central Coast streams to angling, while the Garcia and neighboring streams shrink to a trickle. This scenario places the Garcia’s fish — easy targets in low, clear water — in harm’s way, because poachers often pose as legal anglers. The proposal is currently going through the standard procedure for regulation changes.

The Garcia and I may have parted — the heart is a fickle thing, and we are all prone to wander — but she still haunts my thoughts and sends me dreams. For years, I’ve resisted writing specifically about the Garcia, both to protect my memories and do my part to shield the river from attention. We all know that a river’s reputation can be the enemy of solitude and a good day’s fishing. But on rare occasions, a secret is better shared. I believe this is one of those occasions. Who knows whose life the river may touch, whose sons or daughters may someday find their own defining moment walking its banks on a bluebird winter day? Who knows in what ways the river’s riches — if preserved — may come back to us, the various peoples of this place?

Honestly, I have a soft spot for the romance of poaching. What American doesn’t warm to the outlaw thought of depriving the estate lord of his abundant game? Don’t we all aspire to have that devious twinkle in our eye? Hollywood says we do. Hasn’t it been written that all good anglers are poachers at heart? And isn’t “living off the land” one of our noble ideals of independence? Well, to all those things I say firmly: not here and not now. Adamantly no. Let’s not be passive observers and let a relative few ruin the makings of a good comeback story.

If you are on the Garcia River this winter and you see poaching, report it, dammit.