I often find myself thinking about fishing. It’s not the purposeful, focused process of pondering where I should go, what to pack, what patterns might work. Rather, it is a sort of mind slide that happens during meetings, while waiting in line, or maybe while weed whacking the yard. I just sort of slip into a generic vision of being out on the water somewhere. For me, that water is almost always in a meadow: grassy banks, some wildflowers, the bright sun shining, and I see the smooth glide of water before me.

The Sierra is home to a profusion of wonderful meadows. Some of them tell tales of the hardships of the journey west: Faith, Hope, and Charity. Others are well-known and iconic: Tuolumne, Big and Little Pete, and Monache. There are the large high-alpine meadows such as Crabtree and the countless strings of smaller, anonymous open areas such as those strung along Wallace Creek before it plunges into the Kern trench.

Two of my favorites are located at the eastern base of Sonora Pass. Pickel Meadow and Leavitt Meadow were originally connected by the trail established by the Clark-Skidwell Party. Seventy-five people first used this route in 1853 to cross the Sierra, and the trail was subsequently traveled by Grizzly Adams. In 1854, a second crossing there was attempted by the Duckwall Party, who became stranded in the valley named from their rescue, now the site of Relief Reservoir.

Today, these two meadows, both of which lie astride the West Fork of the Walker River, offer very different faces. Pickel Meadow is right on Highway 108 and receives a lot of fishing pressure. It is also the home of the United States Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center. I have vivid memories of fishing up the river, rounding a corner, and coming upon a group of marines being chewed out while constructing a bridge across the stream. The compound of military structures and landing pads with frequent helicopter activity contrasts sharply with the old buildings of the Leavitt Meadows Pack Station. Highway 108 begins a sharp climb at the edge of Leavitt Meadow and offers the enticing view of the very large meadow stretching out to the peaks of the crest.

Leavitt Meadow is access by the trailhead at the Leavitt Meadows Campground, which is about half a mile east of the meadow itself. The campground is 91/2 miles west of the junctions of Highways 108 and 395. The trailhead can be found at the rear of the campground near Site 12. There is a $5.00 parking fee if you leave your car at the campground. Instead, use the backpacker parking area, which is located about a hundred feet west of the campground. There is a self-issuing wilderness permit station here, as well.

The trail to Leavitt Meadow initially crosses the river via a metal bridge and then quickly climbs to the crest of the ridge beyond the stream. After topping out at the ridge, the trail passes an angler survey box where anglers can record their results for Roosevelt and Land Lakes. Soon thereafter is a junction sign for the trail to Secret Lake and the lakes beyond. A well-worn use trail continues straight ahead at this point and leads back to the meadow and the West Fork of the Walker River. This trail also connects at the head of the meadow to the trail leading to a series of lakes and connections to faraway places, which I’ll discuss in the section below titled “The Highway 108 Backcountry.”

The Characteristics of Meadows

Meadows are special places, and Leavitt Meadow is no exception. They are associated with streams and rivers and are formed when there is a significant decrease in the speed of the flow. This can be the result of obstructions such as rockslides or downed timber or the work of busy beavers. In the case of an obstructionformed meadow, the sediment deposits broaden into a floodplain. Meadows attract a typical community of plants, mainly grasses, flowers, and low growing shrubs, such as sage In some cases, the meadow is able to remain open because the water table is high, which makes the soil too wet to sustain confers. If that water level begins to drop, the meadow can become invaded by conifers, as has happened in Yosemite Valley.

In the Sierra, however, meadows such as Leavitt and Tuolumne were formed as a result of the relatively level gradient in glacially gouged valleys. The glaciers retreated with rising temperatures, leaving behind a series of small lakes and ponds. Later, sediment-laden river flows slowed in these valleys, dropping their loads. Over time, the small lakes filled in, creating today’s meadows.

Because they are so “spongy,” meadows serve an extremely important function in California’s hydrology. In the spring, snowmelt is absorbed in the porous soils, often causing the formation of ponds and those irritating sucking mud bogs. Over the summer, this water is released into the surface flow of the stream, a natural form of water management for every watershed. In addition, the porous nature of the meadow filters out impurities and sediments, which is why wetlands are so favored as a part of water-treatment regimens.

These geological and hydrological features define meadow fishing and its challenges. The course of a slower-moving stream is going to be deflected by obstructions, instead of being able to erode them. Thus, meadow streams are a collection of sinuous curves connected by shallower riffled sections. A meadow stream’s form comes into being through a process of removal and redepositing of the streambed. Erosion is greatest on the downstream (outside) corner of each bend, and deposition is greatest on the upstream (inside) corner of the succeeding curve. Frequently, the inside of the curve develops into a sand or gravel spit.

During periods of low water, the stream stays within its banks and goes through the process just outlined. But during periods of high runoff, it can jump its banks, carve different channels, cause the collapse of banks, and spread deposits throughout the floodplain. It is these events that created the braided streams that form in areas in which a large amount of debris drops quickly. This generally comes where the grade of the stream suddenly decreases or the substrate becomes greatly more porous. If you have ever had the feeling that a stream can change size over the course of its journey through a meadow, you were correct.

The classic configuration is a series of half-moon arcs that are deeply cut at the outside bend, concentrating into a tail area that then forms a riffle or slot that leads into the next pool. These cuts are sometimes deep enough to contain back eddies. Almost invariably, they are deeper than you imagine, are undercut, and are guarded by vegetation. Yes, this is the home of large trout. These fish are supported by the entry riffles, which function as insect factories and add oxygen to the water. The undercut banks provide cover and a slower current in which fish need to expend less energy to hold. Even on small waters, these outside bends contain large fish. In the words of John Gierach, all you need is “an area large enough to hold a football.”

Meadow Tactics

Most meadow streams enter the meadow in a fairly straight line. These areas often support willow growth, which is usually found in the zones of faster current throughout the meadow. These willow sections can be very thick and extensive. They are usually skirted by an angler’s trail, which suggests that most people simply avoid the tangle. Fishing these areas can be really tough, but somebody’s got to do it.

I try to approach the curves of meadow streams from the inside edge. This means that I will be on the wrong side of the stream for every other pool. With smaller creeks, this can be dealt with simply by crossing the stream; otherwise, creative casting and presentations can be required. Keep off the undercut banks themselves, because the sponginess of meadow ground conducts vibrations from footfalls directly into the water. There is often little or no vegetation cover, so I go in with a low profile, taking care to keep my movements slow and my shadow off the water. I want to get in place above the riffle that leads into the pool. Look for fish at the point where the current initially begins to slow at the head of the pool or perhaps on the inside-bend side of the main current. Fish can be found at many points in the pool, and may dart out from anywhere under the bank to seize your fly. Do not ignore the tail out, either.

I try to place my fly in the riffle so that it drifts naturally into the arc of the pool. This is not so easily done, because there are a lot of different current speeds present in these bends, making it difficult to avoid almost instantaneous drag. Because I fool around in these places so frequently, I now find that the majority of my fishing is done using a downstream drift. I know that this runs contrary to the classical notion of upstream dry-fly casting and the maxim “Fish face upstream, so you have to approach them from below,” but the fact is that a lot of stream structure does not lend itself to that approach in meadow streams. In the case of meadow bends, the different current speeds between your downstream casting position and the trout, especially those holding at the head of the pool, almost guarantee instant drag on your fly. You can go a long way toward defeating the “fish face upstream” objection when fishing downstream by using a long and fine leader and learning to cast from your knees.

Because the fly hits the current from a point above the riffle, it can be placed directly into the current line you want to fish. There may be several of these entering the curved pool, and they should each be fished separately. The trick is to get a reserve of slack line above the fly in order to extend the drift. This can be accomplished by using a casting technique such as a stack or pile cast or by having the slack in your hand and releasing it by waggling the rod tip. It takes a while to learn to do the latter smoothly, but the results justify the effort. In either case, the slack must be

more or less directly above the fly. If you are fishing in the willows, you almost always have to release line at or near your feet and keep feeding it while trying to find a line of vision through the tangle of branches. At least this jungle effect minimizes your visibility to the trout. Nymph fishers have known about this technique for many decades and have learned to fish downstream without worrying about violating “dry-fly rules.”

Fishing Leavitt Meadow

The West Fork of the Walker in Leavitt Meadow is a vexation to me because timing is critical. The water levels in this stretch are not controlled by dam releases, which means it fully reflects the seasonal variation in flows caused by snowmelt, with a peak runoff and then the gradual release of water throughout the watershed. Early in the season, the river is high, wide, and deep. By October, the flows are so low that the river is easily crossed, and the trout are concentrated in the remaining pools and undercuts. The river is also susceptible to variations due to storms. Heavy rain cells seem to stall out over the headwaters near the Yosemite border and dump into the upper watershed. This can raise the river by several inches in a matter of a few hours. It also brings a lot of soil runoff, so the river quickly becomes dirty, as well as high. This effect can last for several days. In short, I miss on my timing with the West Fork more often than I hit it right.

As the crow flies, the river flows for about a mile and a half through the meadow. The actual stream distance is probably two to three times that due to the undulating course of the stream, alternating between broad, undercut pooled curves and straighter connections. These latter stretches contain well-defined current slots that are frequently very productive. Although dense willows are situated throughout the meadow, much of the riverbank is open. There are lots of smaller fish in the meadow that are eager to respond to a dry fly, but there are enough large fish to tempt those who measure success in terms of them. In addition to mayfly and caddisfly patterns, make sure you pack your favorite grasshopper imitations.

Leavitt Meadow can come under a fair amount of pressure, particularly at its lower end. The time required to walk all the way up to the head of the meadow to the more forested section of the river and the upper meadow is worth the effort. There is little, if any cover in the meadow or on the trails, so bring water and be sure to hydrate well to combat the effects of the heat. Definitely bring insect repellent early in the summer.

The Highway 108 Backcountry

The Leavitt Meadow trailhead is also a departure point for day hiking, stillwater fishing, overnight camping, and the most direct access to the far backcountry just north of the boundary of Yosemite National Park. A huge expanse of the Sierra can be accessed from this single location, and it would take a long time to sample it all.

One option is to take the Poore Lake–Lane Lake Trail from the Leavitt Meadows Campground. The route is indicated by a sign at the trailhead and starts out with a steep uphill of about a quarter of a mile. At the end of the climb, a shortcut use trail branches to the right and traverses a ridge to Leavitt Meadow. You will find numerous use and stock trails, and the pack station is visible off to the right on the other side of the river. The view as you walk south through the meadow is dominated by Tower Peak (11,755 feet), which marks the northern boundary of Yosemite National Park. The trail follows the eastern edge of the meadow at the base of a ridge, leaving the river.

Two miles from the trailhead, there is a junction with the Secret Lake Trail, which begins further to the east in Pickel Meadow. You are now on the original route of the Clark-Skidwell Sierra traverse. This junction is also the boundary with the Hoover Wilderness Area and is marked with information signs. At this junction, you can backtrack up the Secret Lake Trail to Secret Lake and Poore Lake. If you continue along the trail from the wilderness area sign, you quickly descend to Roosevelt and Lane Lakes. Both lakes are set amid forests of Jeffrey pine resting against a low, rocky, sage-covered ridge. The shoreline of Lane Lake is a bit more open. Both are popular destinations for day hikers, who often cannot resist the urge to cool off with a swim, as well as for short trips by backpackers. Both lakes are shallow and are subject to algae bloom. They contain brook trout. Hiking guides report good fishing at both, but I suspect those observations were made early in the year, before the algae blooms.

If you are looking for a longer overnight trip and for access to the West Walker River in a nonmeadow setting, head up to Fremont Lake, which is a 9-mile one-way hike from the trailhead. Follow the trail past the Lane Lake outlet, which is often dry late in the season. Ford the outlet and follow the trail up an arid, rocky slope to the top of a saddle, which affords excellent views of the West Walker watershed as well as the Sierra Crest. You will pass a lateral trail that leads to Red Top Lake and Hidden Lake, then you descend back down to the river.

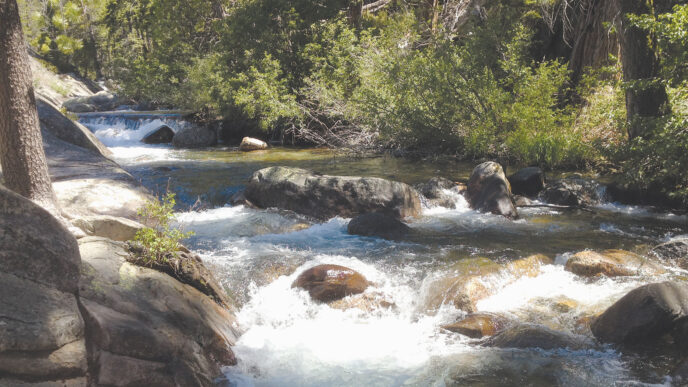

The West Walker here is completely different from the stream in the meadow. It drops quickly through white granite in a series of plunges and pocket water. The glacial history of the area is quite visible here, and the stream runs through a cooling forest, which makes it a pleasure to fish. Along the river, you will see a sign to Fremont Lake and the Chain of Lakes Trail. Take this trail and look for a river ford less than a quarter of a mile downstream of the junction. There are a number of campsites here, if you simply want to lay over and explore the river. To continue to Fremont Lake, ford the West Walker and look for the trail sign on the other side. From the sign, the trail jumps uphill over yet another saddle, which affords views of Tower Peak and leads to Fremont Lake (8,240 feet). Achieving this saddle is a tedious process. The trail is dry and steep and lacks forest cover. It also includes that most dreaded trail feature: false crests. Fremont Lake is a destination for trips out of the pack station, so there is a possibility that you will encounter stock at some point on the trail. Your persistence is rewarded by Fremont Lake, which is a fairly large body of water that sits in a forested bowl surrounded by granite ridges. The forest is lodgepole pine and juniper, and there are campsites in these forested areas. The shoreline is mixed, including shallow, wet, grassy areas with deadfall trees, small meadows, rocky shelves, and in some places, dense trees. There is a lot of open shoreline for casting, though, and the shallows afford wet wading. The lake holds rainbow and brook trout that run to a foot or so in length. The normal fishing guidelines apply at this lake. Dry flies work early and late in the shallow areas, with the fish retreating to deeper water during midday, but they can be coaxed out with beadhead nymphs such as Copper Johns, Flashback Nymphs, or Pheasant Tail Nymphs. Be sure a bring insect repellent.

Beyond Fremont Lake, the possibilities are dazzling. For some reason, I never had fully appreciated what is revealed by a look at a map of the area between the Sonora Pass Road and Tioga Pass. Trail connections would allow trips from Leavitt Meadow to the Kennedy Meadows trailhead through the Emigrant Wilderness, a long loop ending at either Buckeye or Barney Lake trailheads near Bridgeport, or a long trip that would take one to the Tuolumne River. And that’s just scratching the surface of the possibilities for backcountry hiking and angling here.

The Leavitt Meadow trailhead is located in the Toiyabe National Forest, and overnight travel in the Hoover Wilderness requires a wilderness permit. Inquire via the Bridgeport Range Station, (760) 9327070. Permits can be obtained in advance, and this is the way to go. In the past, permits could be picked up at the Pinecrest Ranger Station of the neighboring Stanislaus National Forest so that people coming from the west did not have to travel all the way into Bridgeport to pick up their permit. There is now a self-issue permit box at the backpacker parking area. Overnight camping outside of the wilderness may still require permits, so it is always a good idea to check with the Forest Service to make sure you have what you need. Several trips from Leavitt Meadow are described in Sierra North: Backcountry Trips in California’s Sierra Nevada, 9th edition, by Kathy Morey, Mike White, Stacy Corless, and Thomas Winnett (Wilderness Press, 2005). Useful maps would include the Hoover Wilderness and Yosemite National Park maps from Tom Harrison Maps (http://www.tomharrisonmaps.com/index.html) or the USGS Sonora Pass 7.5-minute topographic map.

If You Go…

Leavitt Meadow is located on the Sonora Pass Road (Highway 108), 9-1/2 miles east of the junction of Highways 108 and 395. The junction is 15 or so miles north of Bridgeport. Fly-fishing equipment and information are available at Kens Sporting Goods, (760) 932-7707, which is located in the middle of Bridgeport. There are several possibilities for meals and lodging there, but grocery choices are limited. Be aware that gas prices in Bridgeport are notorious. Limited grocery options, as well as barbeque, burgers, and lodging, can also be found in the town of Coleville, which is about 10 miles north of the Highway 395–108 junction.

Peter Pumphrey