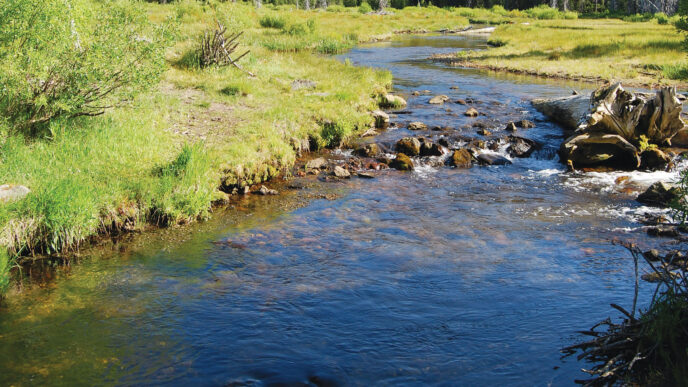

I have never met a meadow that I did not believe would treat me well. Alpine meadows are icons of the high Sierra: the slow-moving stream meandering through a seemingly wide-open landscape of grasses and flowers. Maybe there are a few dramatic clouds in the background, and a light breeze keeps the insects down. I might as well add some rising trout to round out the vision. This is the water that makes my mind scream, “What a place for dry flies! All I need to do is go out there and throw a few around, and I’ll be golden.” Although the reality is often far different, I still favor meadow fishing overfishing in any other setting in the Sierra. It just is not as easy as it appears.

Meadows are found in multiple locations on every stream, even those in the eastern Sierra with its dramatically steep gradients. They come in all sizes, from large valleys that contain several streams, such as in the Bridgeport Valley or Long Valley, to small pocket meadows no larger than an acre, tucked along the alpine headwaters of Sierra creeks. In some places, the stream will weave its way more or less through the center, but in the smaller versions, the creek may ride along the uphill edge of the open space, usually tracing one or two long, broad curves. Some of the higher meadows, such as Crabtree Meadows or those along Wallace Creek, contain typical silt-bottomed pools intermixed with plunge pools. In other pocket meadows, the stream may run straight, hugging the uphill boundary.

For meadow fishing, I look for a significant length of water with at least one bank without tree growth and a gradient that slows the current noticeably in comparison with the other sections of the stream. I know of secret meadows less than a block long tucked into every elevation of every stream I have fished in the eastern Sierra. Some are so small that they do not show up as green areas on the topographic maps, but I know them when I see them, and so do the trout.

Sierra alpine meadows are formed in low spots in the landscape. Generally, these are glacial scours, as with Tuolumne Meadows, but they can also be the result of volcanic activity, such as the caldera of Long Valley. A meadow is often the successor of a former lake, formed by the accumulation of sediment that occurs when a stream’s velocity drops as its gradient flattens. The meadow begins to form at the lake’s inlet and grows from the edges of the recess, moving into the middle of the space. An example of meadow succession in my lifetime has been the transition of Yosemite’s Mirror Lake into Mirror Meadow.

A meadow has its deepest soils at its edges, which, being well drained, are often dry and stable. They are characterized by sedges and displays of wildflowers. As you venture closer to the streambed, the landscape can transition into a wet meadow, acting like a sponge and maintaining sticky mud and muck that are capable of sucking off your shoes.

Because of their moisture, meadows do not support conifer growth, although they can host cottonwoods and, of course, various forms of willow.

Meadows perform important functions for the health of a watershed. A meadow is often composed of deep layers of soil that capture and retain water during the spring runoff. Mountain meadows are the largest surface-storage component of California’s complex water system, and they slowly release stored runoff throughout the summer. They also perform a filtering function by removing impurities from the streams that transect them. Streams grow in size as they cut into the groundwater tables on their way through the meadow. There is a small meadow on the South Fork of Bishop Creek where the entire hillside on one of the banks is a seep that feeds cold water into that section of the stream throughout the year. This is common in meadow streams. The notion that the stream leaving a large meadow is bigger than it was on entry is not an illusion. Streams frequently enter a meadow as a narrow, fast-water channel and then slow and spread. The slower water is more easily deflected and forms sinuous curves, even oxbows.

The features of meadow formation and hydrology have important consequences for the fish and the fishing. The wider streambeds often appear to lack structure and obvious midstream holding areas for fish. This appearance is a deception. The structure in terms of depth and current flows is there, but you have to search it out. The trout have to do less work in the slower currents, which allows them to be a bit more selective and less inclined to move out of the foam lines. The fish have more time to evaluate possible food and potentially can achieve greater size. For the fly fisher, these water conditions place a premium on accurate placement of the fly and delicate presentations and pickups.

Streambed sediments often are not as productive of the same volume and diversity of insect populations as might be found in other locations within the same watershed. And the lack of forest means that when the sun is high and the light is bright, angling in the middle of the day is less productive. You are far more visible to the fish, which are often unbelievably spooky. This means you need to move low and slowly. Casts should be made from as far back from the stream edge as possible, often from a kneeling position.

Fishing meadow streams is not a stroll in the park. It often involves slogging through mud, sinking into holes between tufts of grass or sedge, and getting tangled up in willow branches. There is no shade, but plenty of reflected sun off the water, so go heavy on the sunscreen. Keep an eye on the sky. In Upper Crabtree Meadow, I learned my graphite fly rod was the tallest object in the area during a thunderstorm.

Classic long-distance casting techniques are not worth a whole lot on meadow water. Fly fishers rely instead on roll casts, side casts, where the line sweeps horizontally upstream and downstream prior to the cast, and “casts” in which a pile of line is dumped upstream of a prospective trout. I end up doing a lot of downstream drifting. This demands a good deal of concentration so that the line remains slack enough to allow for drift, but tight enough to have a chance to set the hook. There is a point at which the length of line out in the drift pretty much precludes any chance at making a hookup. Connecting with the fish with this presentation is more difficult anyway, because you are setting the hook with a movement in the direction that pulls the fly out of the fish’s mouth. The set needs to be a little slower in response to the take.

When you drift a fly downstream in this manner, you become aware of the fact that even a featureless meadow stream has numerous currents between its banks. It is really tricky to get the fly into the correct current for the fish you have sighted without the approach being deflected by other currents between you and the target. One solution is to put yourself in a spot where the rod tip is directly over the current you want to ride. Another approach is to try to throw upstream mends at the outset of the “cast” into the current you want. In either event, I have to force myself to concentrate on specific targets with the idea of hitting what is a narrow target zone.

Fishing meadows is not a process of blind casting. Because the fish are so easily alarmed, movements and casts need to be kept to a minimum. There is a big payoff for taking time to look over the stream. Search for indications of structure, particularly varying depths. You are also looking for signs of fish — rises, bulging, or flashes. Watch for odd-looking disruptions of the surface. A month or so ago, I was on McGee Creek and saw what looked like a wake repeatedly passing through a spot at the head of a pool. I tried the spot, but missed the strike. A week later, the wake wasn’t there anymore, but its source, a foot-long rainbow, was.

Meadow water has characteristic hot spots. Focus on the edges. Meadow streams run through dirt and sod, allowing the water to carve out undercuts along the banks where the current speed is a little faster than toward the middle of the stream. Not only is the bed of the stream cut into, creating slots of greater depth along the sides, but the stream also hollows out areas beneath the bank itself. If you take a look at the large chunks of collapsed banks, you can get an idea of how surprisingly far back these cuts can extend. It goes without saying that these are prime locations for fish. Undercut banks provide protection from predators, bright glare, and higher temperatures. They often are fed by strong food-carrying currents, and being at the stream edge of the meadow, provide the fish with a diet of wayward terrestrials.

Often, only one of the banks along a given stretch will be undercut. For those on my side of the creek, I favor a downstream drift, exploring short segments of water from as far back from the edge as I can be. Many of these drifts start out as a sort of dapping of the fly directly down onto the water, followed by furiously feeding slack. There are times when the fly cannot be seen and the strike is signaled by sound or a response from the line. There are few takes as exciting as that from a decent-sized fish hidden back beneath a shield of overhanging grass. This same technique can be used effectively when fishing small creeks with dense willows.

An undercut on the opposite bank presents problems due to the fact that the currents between you and the far edge are likely to be running at multiple speeds, making it extremely difficult to achieve a drag-free float. You can approach this with a cast across the creek and slightly above the prospective fish, but you have to understand that there will be drag in very short order. This is when you need to know the exact location of your target, because you may be able to achieve a natural float that’s less than a yard long. The fly needs to land lightly, and the pickup must be clean. There are not a lot of second opportunities if you botch the first presentation.

Meadows also allow for broad turns, and productive water is found at the curved sections of the creek. Each of these is capable of creating a productive bend pool or slot. The current flows faster at the outside of the bend. This faster current scours out the far side, while the slower current deposits a sort of a beach on the inner side of each bend. Fish are found all along the turn, but the tail where the water fans into the next riffle connector is especially productive. The turns in the stream alternate between left and right bends, such that you will be on the inside of roughly half of them if you fish from a single side of the creek. Some of these meadow creeks are small enough that this can be dealt with by simply crossing the stream — carefully, or else you will spook every fish in the area. On larger waters, you will have to have an approach for fishing with the deep outside slot on both your side and across the intervening currents. There are also a lot of willows in these places, and they frequently grow tall and wide enough that the water runs through a tunnel of branches. These are places that call for careful initial observation and a dash of creativity in your casting.

If you are on the deep-slotted side of the stream, start with a “dap drop” over the top of the grass into the deep runs on your side of the bank. Start hard against the bank and then move farther out into the current. Pay careful attention to the path taken by the fly, because it will often be carried away from the target, unless you are careful to keep both the fly and the line entirely within the current line you are trying to fish. It is often quite difficult to fish the upper stretch of these pools by casting upstream, due to the presence of conflicting currents. I often miss these extra currents until I watch them screw up what I believed was a perfect placement. You may have to fish the upper half of the curve pool by drifting from above and the downstream section by casting up from the shallower water below. There is a lot of moving around in this type of fishing. If you do fish the entire bend from below, aim upstream casts for the edge of the tongue that enters the bend, so that the fly stays in tight to the bank. Otherwise, the current will sweep the fly out and away from the productive water, leaving a clear wake that will put down the fish. Again, you need to make short casts fished with surgical precision.

If you are on the shallow “inside” bank, you are going to have challenges. The slow current at your feet is sure to alter any drift into the faster current at the far side. I, at least, cannot achieve long drifts and have given up trying, opting for shorter tosses and having to do more work. The top-half downstream drift, bottomhalf upstream cast approach works from the inside edge, as well, but it is a more difficult task. There are times when I will just leapfrog these curves going one way, cross the stream, and pick up the unfished ones on the way back.

These bends are connected by stretches of faster, straighter water that run from the tail of upstream bend pools, fan out across the width of the stream, and then reform into slots leading into the outside of a downstream curve. These generally have gravel or cobble bottoms and are factories for fish food. The riffle water drives into the far bank, often forming an eddy at the head of the curve. An eddy is a hotbed of conflicting currents that make it difficult to get any kind of natural drift. One way to deal with this is to maneuver yourself close enough to be able to hold the rod tip over the eddy, thus avoiding placing line across the entry current. This is a workable strategy on smaller streams, but may become difficult if wading is involved. Moving in the water is liable to flush every fish for several yards and stir up clouds of fine sediment. While fishing the eddy, remember that the current in them will run “backward,” so the trout will be oriented in the opposite direction of those in the remainder of the stream. Eddy pools can be quite deep, meaning that they are not necessarily the best spot to float a dry. If you fish them and aren’t experiencing surface takes, be open to the idea of using some sort of subsurface imitation. The eddy does not lend itself to a subsurface drift, however. I try to place the fly directly into the eddy, let it sink slowly, and then raise it in steps back toward the top. Again, you have to keep line out of the other currents.

The glide downstream from the eddy, where the current has reformed, is a productive place to fish. This slot usually leads to a short riffle that flows into the head of the next bend pool. Fish are found not only in the deeper lead-out current, but also in the shallow riffle. As already noted, the currents in the eddy can make presentation difficult.

Do not ignore these riffles, particularly early in the season. Although the water is shallow and offers little in the way of protection, it is more highly oxygenated in warm times, offers warmer water in cold weather, and continually stirs up and carries food. Surprisingly large fish can respond to a dry fly floated along the surface of these connectors.

Although the initial reaction to a meadow setting is to think dry fly, there are good reasons to bring your nymphing gear. Middays in the summer can be bright, and the fish are looking for respite from the glare. They are likely to be found in the deeper water and are not oriented toward the surface. Many sections of meadow waters are quite deep. Overall, far less than half the feeding that goes on is on the surface. The relatively faster water that leads into the curve pools and eddies carry significant numbers of underwater invertebrates to trout who are just waiting for them to appear. The trick, in these deeper areas, particularly the eddy pools, is to keep slack out of your line so that you can set the hook at the first indication of a strike. As to my meadow fly box: grasses and grasshoppers go together. A friend of mine and I were walking downstream in Long Valley and spooked a hopper that flew into the creek and disappeared in an instant. We had no trouble deciding on patterns that day. In his book Fish Food, Ralph Cutter describes three factors that come into play when fishing hopper patterns. The first is abundance: the fish have to be used to seeing the actual insects. The second is movement: real grasshoppers struggle in the water, especially when they first make contact. This is why a less-than-perfect “splat cast” can work with this pattern. The third is size: your imitation needs to be no bigger than the natural. I carry grasshoppers down to size 16, because I fish a lot of small waters, and I fish parachute ties because I am getting old and need the fly’s post to spot it on the water. For me, the smaller and simpler the pattern, the better the result. Other terrestrial imitations likewise work well in this setting. I also favor caddis and caddis emerger patterns for the afternoons and mayfly ties for overcast days. Midges are useful at all times.

A few days ago, my life had made me cranky. I decided to head to a little stretch of meadow twenty or thirty yards long in the headwaters area of an eastern Sierra stream. The walk in from the access point is a bit more than a mile. It was early in the morning, and the heat that would move in later was just a threat. I once spotted a mountain lion from this trail. Today, I jumped three deer, which bounded across the creek and up the hill with astounding speed and grace. I saw a pair of western tanagers and a red-breasted sapsucker, and a flock of mountain chickadees joined me in the willows. The water in this stretch is completely clear and runs over a white sand streambed. The creek is deep at both edges, and it supports lush weed beds and is engulfed in willows. It is a difficult place for me to fish, but it is worth the challenge to be in such beauty. I took rainbows from expected places in expected ways and a couple of unexpected “surprise fish.” This little meadow has been good to me. But aren’t they all?