GEOLOGY

By Jeff Ludlow

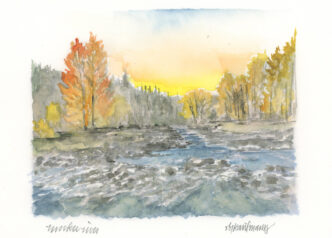

Illustrations by Obi Kaufmann

To understand the geology of the Truckee River, one must start at its source, Lake Tahoe. This jewel of the Sierra Nevada lies at the western edge of the Basin and Range geomorphic province and is a classic example of “horst and graben” geology. The Sierra Nevada Range on the west and the Carson Range on the east are the upthrown faulted horsts (ranges) and the valley between is the down-dropped graben (basin), which formed starting approximately 7.4 million years ago. The basin was dammed just west of Tahoe City with volcanic rocks from basalt and andesite flows, thus creating Lake Tahoe. Over time, the rocks eroded, the dam was breached, and the Truckee River was born.

The Truckee River flows for over 120 miles from Lake Tahoe to its terminus Pyramid Lake and is fed by a watershed covering over 3,000 square miles. This watershed is known as an endorheic (closed) basin where the drainage system retains its water and there are no outlets to the ocean.

The geology of the Truckee River can be described in the following sections: the Upper Truckee Canyon starting at Lake Tahoe, the Truckee Basin around the town of Truckee, the Lower Truckee Canyon beginning near Boca, Truckee Valley around the City of Reno, and the Lower Truckee River to Pyramid Lake.

The Upper Truckee Canyon is surrounded volcanic rocks of basalt, andesite and lahars, formed from a mix of water, volcanic gas, ash and rock. These rocks are from eruptions thought to be from numerous vents around the region rather than from a single volcano. Ice Age glaciation significantly shaped the Upper Truckee River and dispersed very large granite boulders from the high Sierra to areas downriver beyond Reno, resulting from catastrophic flooding. During the Pleistocene Epoch, the high Sierra Nevada was covered in ice and glaciers flowed down Bear Creek (Alpine Meadows) and Squaw Creek, which created massive ice dams across the Truckee River. Lake levels then rose to elevations hundreds of feet higher than seen today, transforming Lake Tahoe into what is known as a “proglacial lake,” a lake dammed behind glacial ice. As the water rose against these ice dams, the glaciers were “floated” and eventually failed, releasing enormous amounts of water from the lake, causing massive flooding and ice rafts that transported boulders the size of cars down river to points beyond Reno. Evidence of this catastrophic flooding is observed throughout the river system with enormous boulders of granite from the high Sierra deposited dozens of miles downriver from where the granite originated. This phenomenon of ice-dammed proglacial lakes collapsing and creating catastrophic floods is common in Iceland today, where the term “jökulhlaup” describes such an event.

Further downriver in the Truckee Basin, the river gradient flattens and turns east. In this section, glacial moraine and outwash (boulders, cobbles, gravel, sand and silt), and alluvial and lacustrine (lake sediment) deposits are observed. The glacial deposits resulted from the melting Pleistocene glaciers, while the older alluvial and lacustrine deposits are from an ancient lake that formed in this area around Truckee when the river was dammed by volcanic flows from vents near Juniper Flat south of Boca.

In the Lower Canyon section of the river east of Boca, volcanic deposits of similar type and age to those seen in the Upper Canyon are again observed. At this point, the river gradient steepens as it cuts its way through the northern flank of the Carson Range creating the deep canyon structure of the river, known as the Grand Canyon of the Truckee. However, the steep river gradient in this area was thought to be flatter in earlier times. The river once flowed across the nearly flat volcanic deposits and established its current course. As tectonic uplift of the area progressed over the millennia, the river maintained its course and the rate of downcutting of the river canyon exceeded the rate of tectonic uplift creating what is known as an antecedent stream and the deep river canyon seen today.

The final leg of our geological journey along the Truckee River takes us to the Truckee Valley through Reno and Sparks where volcanic rocks again are observed along with glacial outwash and alluvial sediments. Anomalous among the rocks in the riverbed, however, are the large boulders of granite transported over 100 miles from the high Sierra during the catastrophic Ice-Age floods that shaped the river. Towards its terminus, the Truckee River turns north flowing through lacustrine deposits and tufa rocks of the ancient Lake Lahontan to end its journey in Pyramid Lake.

- Gardner, James V, et al, 2000. Morphology and processes in Lake Tahoe (California – Nevada). Geological Society of America Bulletin May; v. 112; no. 5; p. 736-746

- Birkeland, Peter W., 1963. Pleistocene Volcanism and Deformation of the Truckee Area, North of Lake Tahoe, California. GSA Bulletin, v. 74, p. 1453-1464, December.

- Konigsmark, Ted, 2002. Geologic Trips, Sierra Nevada. GeoPres ISBN 0-9661316-5-7.

- Saucedo, George J., 2005. Geologic Map of the Lake Tahoe Basin California and Nevada. California Geological Survey.

- Ramelli, A.R., et al, 2011. Preliminary revised geologic maps of the Reno urban area, Nevada. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Open-File Report 11-7, 3 plates.

- Koehler, Rich D., et al, 2016. A river runs through it-geology along the Truckee River valley from Reno to Pyramid Lake. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Educational Series E-59.

- Kortemeier, Winifred, et al, 2018. Pleistocene volcanism and shifting shorelines at Lake Tahoe, California. Geosphere 14(2):812-834.

BIRDS – AMERICAN DIPPER

By Sarah Hockensmith, Outreach Director, Naturalist

Tahoe Institute for Natural Sciences

Spring in the Sierra Nevada brings swollen creeks from snowmelt, a symphony of new growth, and the melody of bird song. If you happen to be near fast-moving, clean water in the higher elevations, you may hear the distinctive trill and chatter of the American Dipper (Cinclus mexicanus). This fascinating bird is a true mountain dweller, thriving in turbulent rivers and streams.

At first glance, the American Dipper’s gray plumage may appear unremarkable, but a closer look reveals its striking white eyelids that become visible with each blink. While it may not immediately stand out for its coloration, the American Dipper is far from dull. It exhibits extraordinary behaviors that set it apart from other songbirds. Remarkably, it is the only songbird known to plunge into and completely submerge itself in rushing waterfalls, rivers, and streams. Beneath the water’s surface, the Dipper flips over small rocks and pebbles in search of macroinvertebrates, mainly benthic nymphs and larvae. This stunning feat of diving and submersion is just one of its many talents.

The American Dipper can also capture flying insects mid-air, adding to its already impressive skills. With its body bobbing rhythmically as it walks along riverbanks, the Dipper remains unfazed by the tumultuous waters, making it a beloved sight for river enthusiasts and fishermen alike. Whether seen or only heard, the American Dipper’s unique antics make it a welcome addition to mountain rivers throughout the West.

FLORA – WAVY-LEAVED PAINTBRUSH

By Sarah Hockensmith, Outreach Director, Naturalist

Tahoe Institute for Natural Sciences

The streamside habitats of the Truckee River and Little Truckee offer an array of rich smells, stunning views, and lasting memories. Among the many plants that thrive in these lush environments is the Wavy-leaved Paintbrush (Castilleja applegatei), a striking plant known for its brilliant scarlet bracts that often overshadow its yellow-green flowers. These vibrant clusters of color brighten the landscape, especially in areas rich with moisture.

Like other species of paintbrush, the Wavy-leaved Paintbrush is a hemiparasite, meaning it partially relies on other plants for nutrients. While it still engages in photosynthesis and draws nutrients from the soil, it also taps into the root systems of nearby plants for added sustenance. Using specialized modified roots called haustoria, which pierce the roots of their neighbors, the paintbrush siphons water and nutrients from its host plants. This helps it thrive, even in poorer soils where other plants may struggle.

The bright red flowers of the Wavy-leaved Paintbrush attract a variety of pollinators, from beetles to butterflies. However, it’s the hummingbirds who are most drawn to the vibrant crimson hues. These birds rely on the caloric nectar provided by the paintbrush during their seasonal journeys to and through the Truckee and Tahoe regions, and in exchange, the paintbrush relies on the birds’ visits to exchange pollen from flower to flower to ensure future generations of these crimson beauties.

Whether brightening riverbanks or standing tall in moist meadows, the Wavy-leaved Paintbrush is a beautiful plant that adds vivid color to the Truckee landscape. Its unique method of acquiring nutrients, along with its striking blossoms, contribute to the region’s natural beauty and remind us of the delicate balance between plants and their environments.

About Obi

Illustrator Obi Kaufmann is an award-winning author of many best-selling books on California’s ecology, biodiversity, and geography. His 2017 book The California Field Atlas, currently in its seventh printing, recontextualized popular ideas about California’s more-than-human world. His next books, The State of Water; Understanding California’s Most Precious Resource, and the California Lands Trilogy: The Forests of California, The Coasts of California, and The Deserts of California present a comprehensive survey of California’s physiography and its biogeography in terms of its evolutionary past and its unfolding future. The last in the series, The State of Fire; Why California Burns was just released in September 2024.