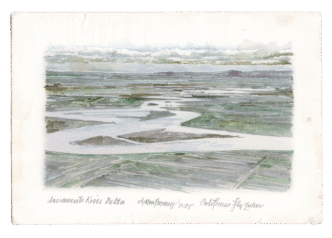

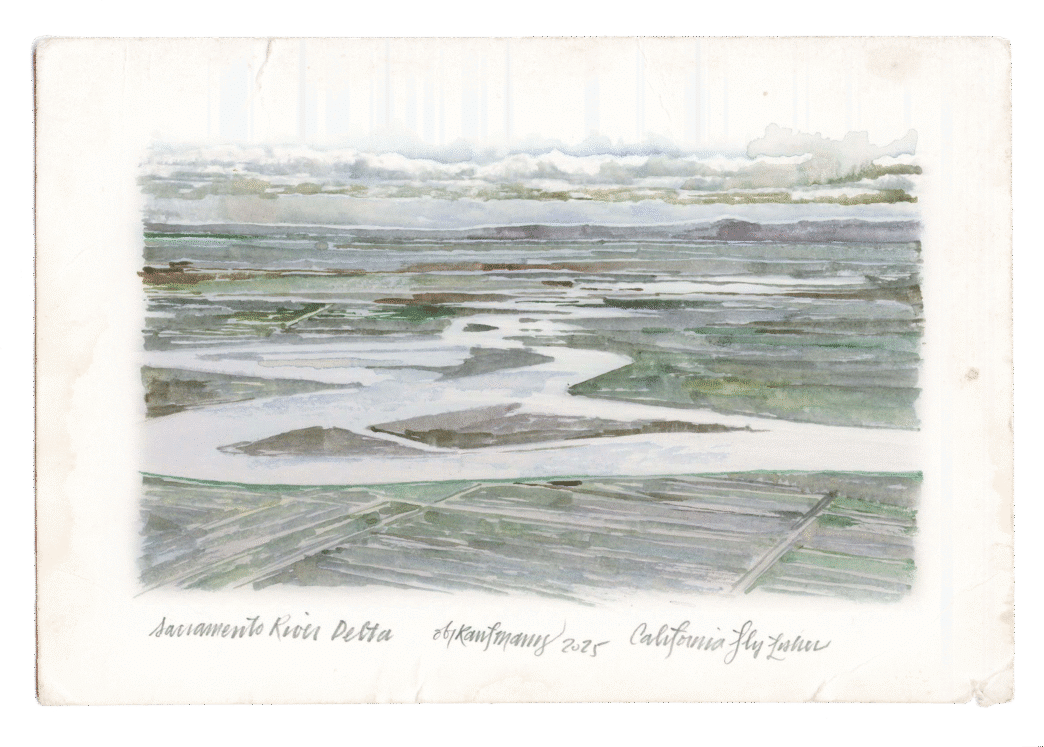

GEOLOGY: SACRAMENTO-SAN JOAQUIN DELTA

By Jeff Ludlow

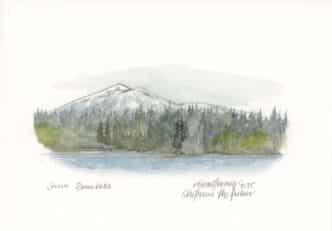

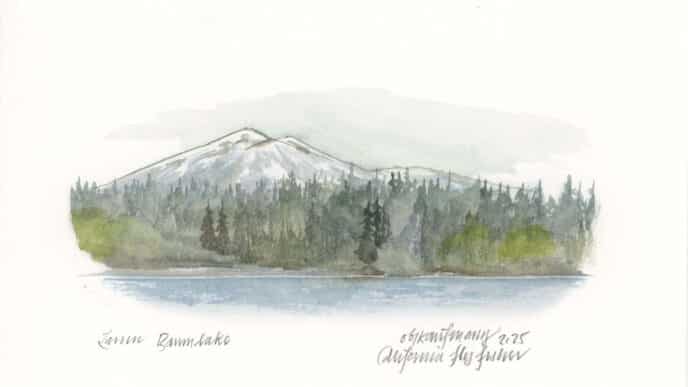

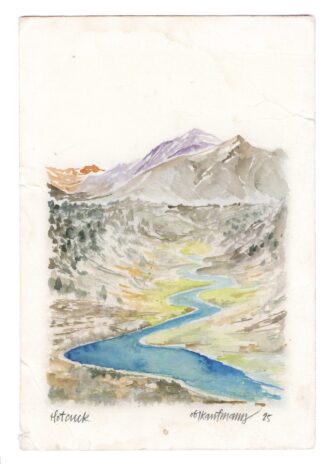

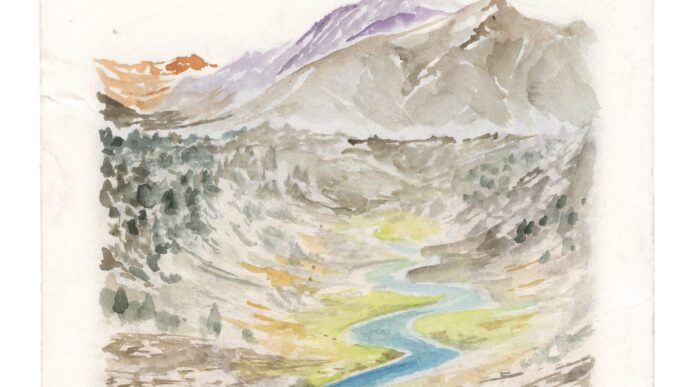

Illustrations by Obi Kaufmann

The beating heart of California’s rivers is the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (Delta). Her arteries flow from as far north as the Cascade Mountains down to the Sacramento River watershed, and from as far south as the Southern Sierra Nevada to the San Joaquin River watershed. The Delta receives a staggering amount of the state’s water, with runoff from about 40 percent of California and approximately 50 percent of the state’s total streamflow. Though like any uncared-for heart, the Delta is not well. First, let’s start with the origin story.

The Delta was formerly at the bottom of Lake Corcoran, a large inland lake that covered most of the Central Valley approximately 750,000 years ago. During this time, the Sierra Nevada were covered with ice and sea levels were about 400 feet lower than today. The San Francisco Bay was a broad river valley that extended out to the Farallon Islands. Initially, Lake Corcoran drained through the Coast Range into the Salinas River watershed to Monterey Bay. However, tectonic uplift of the southern Coast Range approximately 620,000 years ago sealed this outlet and a new one formed in the next lowest notch in the range, near present day Crockett and Benicia. What likely resulted was a torrent of water draining the lake and carving out the narrow Carquinez Strait. This new outlet effectively drained the ancient Lake Corcoran and the modern-day course of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers were set; the Delta was born.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is known as an Inverse Delta. Typically, deltas grow downriver and seaward as rivers deposit sediments into an open body of water, like the Mississippi Delta. Because of the massive amount of stream flow that is restricted at the narrow Carquinez Straits, the rivers have “backed up” behind the straits and thus dropped their sediment before they reach an open body of water. What results is an upriver landward growth of the Delta over time. Additionally, during post-glacial sea level rise, starting approximately 10,000 years ago, rising seas and tidal action added to the upriver growth of the Delta. Historically, tidal influences have been measured as far inland as the Cosumnes River, and the salinity freshwater interface at Cortland on the Sacramento River.

The upriver landward growth of the Delta over the millennia can also be seen in its stratigraphic record. The most common vertical sequence of soil deposits shows peat and mud of tidal marshes directly overlying alluvial sediments of rivers, a sequence recording landward spread of tidal environments rather than seaward migration of fluvial environments. This overlapping soil sequence shows the encroaching intertidal marsh deposits on the older soils that were deposited by rivers as sea level rose and the Delta advanced landward.

Now, we return to the sinking heart of California’s river system. The Delta is one of the state’s largest and most altered ecosystems, resulting primarily from agricultural use and the massive north-to-south transfer of water. In the late 1800s, levees were built along the steam channels protecting them from flooding and island tracts were drained for agricultural purposes. This resulted in land subsidence to elevations as low as 15 feet below sea level. As the land subsides, levees become vulnerable to failure and thus threaten water quality. Most subsidence in the Delta is caused by oxidation of organic carbon in peat. In its saturated condition, peat is anaerobic (oxygen-poor). When peat is drained for agricultural use, it becomes aerobic (oxygen-rich) and releases great amounts of carbon dioxide (a well-known greenhouse gas) to the atmosphere. As the gas releases, the peat collapses or settles causing land subsidence.

The other consequence of land subsidence relates to the quality of Delta water transferred south. The western Delta islands are believed to slow the inland spread of saltwater from the Bay into the Delta. If these islands flood, the transferred Delta water may become too saline for use. To mitigate this risk, Folsom, Shasta and Oroville dams release prescribed amounts of freshwater in summer and fall to push saltwater west, away from the pumps that transfer Delta water for agricultural and municipal use.

Like many mitigative solutions to environmental impact, wildlife habitat restoration is an effective method to slow land subsidence in the Delta and to maintain water quality. Federal and state restoration programs are focused on the periphery of the Delta and away from the central islands where significant settlement has already occurred. The combined issues of Delta land subsidence, water quality, and habitat restoration will continue to present interrelated challenges for California water managers for years to come.

- Atwater, Brian F., 1982. Geologic Maps of the Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta, California. US Geological Survey

- Ingebritsen, S.E., US Geological Survey, Ikehara, Marti E., National Geodetic Survey. Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, USGS Publications Circ 1182 11Delta

- Rogers, David J., Storesund, Rune, 2011. Geologic Setting of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Berkeley NSF RESIN Project Meeting, January 26.

- Wong, Kathleen, 2006. “Carquinez Breakthrough.” Bay Nature Magazine, Fall.

THE MAJESTIC RETURN OF THE SANDHILL CRANES

By Jane H. Adams, Lodi Sandhill Crane Association, Board of Directors

Each fall, one of California’s most extraordinary wildlife spectacles takes place in the Central Valley. After traveling thousands of miles from their breeding summer grounds in the northern U.S., Canada, and even Siberia, flocks of sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis) arrive to spend the winter months in California’s wetlands and agricultural fields.

Standing nearly four feet tall with a wingspan that can stretch seven feet, sandhill cranes are unmistakable. Their long legs, graceful necks, and red-capped heads make them easy to spot against the golden light of a Central Valley sunset. But what often captures people most is their sound—a loud, rolling trumpet call that echoes across the sky and marshes.

For centuries, the Central Valley’s natural floodplains provided perfect wintering habitat for cranes. Today, much of that land has been converted to farms and development. Surprisingly, cranes have adapted, like they have done for thousands of years, feeding in harvested corn and grain fields while still relying on the remaining wetlands for roosting at night.

Conservation areas such as the Woodbridge Ecological Reserve in the Delta, managed by the State of California Department of Fish and Wildlife; the Cosumnes River Preserve, managed by seven land-owning partners; and Staten Island managed by The Nature Conservancy, all play a vital role in giving the birds safe refuge for roosting and food.

Sandhill cranes are also known for their spectacular dances which strengthen the pair bond. Even in winter, pairs can be seen leaping, bowing, and flapping their wings in playful displays that strengthen their lifelong bonds. These performances are a favorite sight for birdwatchers and photographers.

For many Californians, seeing the cranes each year is more than just a glimpse of wildlife—it’s a seasonal tradition and a reminder of the importance of preserving open spaces. Festivals, like the Lodi Sandhill Crane Festival, celebrate their arrival and invite people to connect with nature.

The 2025 Lodi Sandhill Crane Festival will be held November 7 – 9 at the Hutchins Street Square, 125 S. Hutchins Street, Lodi, California. The free festival features an art show, Friday night reception with silent auction, presentations on sandhill cranes and other wildlife, vendors, and hands-on family activities. Tours, which require pre-registration, are scheduled for early morning fly-outs, during the day, and evening fly-ins.

As long as wetlands and farmland remain available, these ancient birds—whose ancestors date back millions of years—will continue to grace the Central Valley with their presence, inspiring awe and wonder for generations to come.nfazed by the tumultuous waters, making it a beloved sight for river enthusiasts and fishermen alike. Whether seen or only heard, the American Dipper’s unique antics make it a welcome addition to mountain rivers throughout the West.

About Jane

Jane Adams discovered Sandhill Cranes after moving to Sacramento and attending the Lodi Sandhill Crane Festival. Captivated, she is a 20-year docent with California Fish and Wildlife and volunteers at Audubon’s Rowe Sanctuary in Nebraska. As a Lodi Sandhill Crane Association board member, she shares her passion for educating others about these birds.

About Obi

Illustrator Obi Kaufmann is an award-winning author of many best-selling books on California’s ecology, biodiversity, and geography. His 2017 book The California Field Atlas, currently in its seventh printing, recontextualized popular ideas about California’s more-than-human world. His next books, The State of Water; Understanding California’s Most Precious Resource, and the California Lands Trilogy: The Forests of California, The Coasts of California, and The Deserts of California present a comprehensive survey of California’s physiography and its biogeography in terms of its evolutionary past and its unfolding future. The last in the series, The State of Fire; Why California Burns was released in September 2024.