An Overlooked Gem in the High Desert

Eagle Lake will always remind me of my good friend, Jay Fair (rest his kind soul)—a man who taught as much about life as he did about fly fishing.

My first trip there was far from smooth: freezing nights, leaky waders, and a shaky start. But thanks to Jay’s advice and the kindness of strangers who soon became friends, the lake gave me more than fish. It gave me lessons I’ll carry forever.

That trip marked my baptism into the rewarding world of stillwater fly fishing. After hearing Jay speak at a local club, I became convinced that late October was the ideal time to go. I brought along my oldest son, who was 11 at the time, and we headed to Spaulding, where I thought I had reserved a small cabin for our four-night stay. We arrived around 2 p.m., eager to unload and prepare for the next day’s adventure—only to be directed to the “Ritz,” a shack with two twin beds, one solid wall, three screened walls, a roof, and a fire pit and picnic table out front. That was it.

Fortunately, a fellow club member had suggested I pack a small portable heater. Good advice because we definitely needed it. That first night, the temperature dropped to 29°F, with winds gusting to 20 mph until nearly 3:30 a.m. My son and I shoved the two beds together in front of the heater, zipped our sleeping bags together, layered on every piece of clothing we had, and huddled in the least windy corner. Sunrise couldn’t come soon enough.

Running on little sleep, we rose at 5 a.m., ate a quick breakfast, and were on the water by 6:15. Waders on, fins strapped, float tubes launched, rods ready—we started fishing along the tule edges just after 7 a.m. An hour later, my son said his legs felt cold. I chalked it up to the rough night and told him the sun would warm him soon. But another hour passed with no bites, and when I noticed him shivering, I knew something was wrong. Back on shore, we discovered his waders had sprung a leak just below the waistline.

Thankfully, we had dry clothes in the truck. While he changed, I packed up and took him back to the campground for a hot shower, worried less about fishing and more about facing another freezing night in that shack.

At the camp office, I explained our situation and mentioned that we might have to cut the trip short. The manager asked me to wait, made a quick phone call, and returned with good news: The owner had an RV on-site with a heater we could use. We gratefully accepted.

By the time we moved in and unpacked, it was past 1 p.m., so we took a much-needed nap. Word of our mishap spread quickly, and by 3 p.m. a club member knocked on our RV door with a backup pair of waders that fit my son perfectly. That act of kindness meant a lot. His original waders had dried enough to patch, so we worked on that too and planned to double-layer them the next day, just in case. After dinner, my son had one more request: ice cream.

As luck would have it, we ran into Jay and his son Glenn at the campground store. Jay had become a close family friend after helping my son with fly tying. When he asked how our day had gone, we told him the story. He smiled knowingly and said, “Tomorrow will be better.” Then he asked, “Joe, while you two were fishing today, did you ever feel like you were dragging your fly over a blade of grass or brushing up against the tules?” My son and I answered in unison: “Yes.” Jay nodded. “Next time you feel that, do me a favor—set the hook.” We thanked him and headed back to the RV, warmed by more than just the heater that night.

The next morning, we were ready. On my second cast, I felt that same subtle tug, like I’d snagged a blade of grass. I set the hook, just as Jay had advised, and landed a beautiful 21-inch Eagle Lake Rainbow Trout. On his fourth cast, my son hooked and landed a 20-incher. By 11 a.m., we had caught and released 14 fish between us.

That evening, we saw Jay and Glenn again. Jay grinned and asked, “Well, how was your second day?” He was delighted to hear his advice had made all the difference. He explained that as trout cruise, they quickly suck in food but spit it right back out if it doesn’t seem edible. Eagle Lake, he told us, isn’t just a fishing destination—it’s a place to learn.

That lesson rang true for both my son and me. The kindness we received from Jay, Glenn, the camp staff, and fellow anglers made the trip unforgettable. It wasn’t just about the fish we caught—it became a lifelong memory.

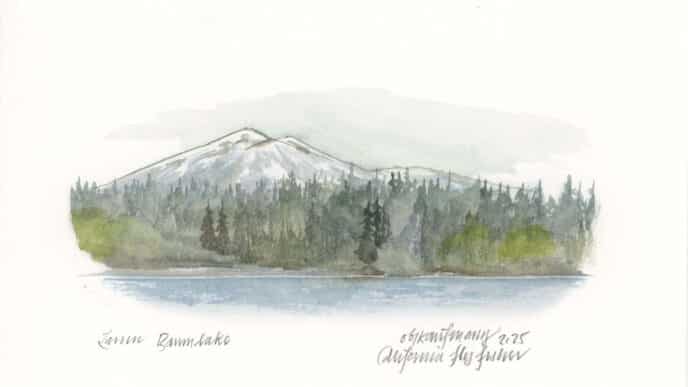

EAGLE LAKE—CALIFORNIA’S STILLWATER TREASURE

Nestled in the northeastern Sierra Nevada at 5,100 feet, Eagle Lake is California’s second-largest natural freshwater lake. Often overlooked, it remains one of the state’s most underrated stillwater fly-fishing destinations. Just 16 miles north of Susanville, and within a scenic two-hour drive from Reno or two and a half from Redding, Eagle Lake offers rugged beauty amidst a rich aquatic ecosystem that draws anglers from all over.

What makes Eagle Lake truly special, though, isn’t just the scenery—it’s the fish. The lake is home to the famous Eagle Lake rainbow trout, a California Heritage Trout renowned for its resilience. They grow quickly thanks to the abundant supply of food and an ecosystem that provides ideal habitat. The best time for anglers to experience Eagle Lake begins in the fall and extends into winter. The lake truly offers one of the most naturally rugged yet serene settings in the state.

THE LAKE AND ITS BASINS

Eagle Lake is an endorheic system, meaning it has no natural outlet so its water levels fluctuate dramatically with seasonal snow and rain. It is divided into three distinct basins, each with its own unique characteristics:

- North Basin — Shallow (about 15 feet), bordering high desert terrain with sagebrush, grassy meadows, and rocky shoreline.

- Central Basin — About 20 feet deep, a transition zone where pines meet sagebrush and grasslands.

- South Basin — The deepest section (nearly 90 feet), ringed by cedar and pine that taper into meadows and rock.

Little Troxel Point and Buck’s Point connect North and Central basins while the Central and South basins are linked by a shallow, rocky channel between Pelican Point and Youth Camp where boats are frequently damaged on submerged rock piles, requiring rescue.

EAGLE LAKE RAINBOW TROUT

Eagle Lake home to Oncorhynchus mykiss aquilarum, a subspecies of rainbow trout found nowhere else. These trout can be identified by white-tipped fins, straight (rather than forked) tails, and a faint pink lateral line with irregular spotting that fades toward the belly. Unlike other rainbows, the males do not develop a pronounced “kipe” (hooked jaw).

Due to water fluctuations and the loss of natural spawning habitat, these trout are listed as a California “species of special concern.” While Pine Creek—on the west side of the Central Basin—was historically the only spawning tributary, years of drought and low water levels have made it unreliable. In response, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, along with conservation groups, established a rearing program to ensure the survival of the species. Adults are trapped near Pine Creek, their eggs and milt collected, and the fertilized eggs raised in hatcheries— Crystal Lake, Mt. Shasta, and Darrah Springs. After 18 months, the young trout are released back into Eagle Lake and beyond. Remarkably, they thrive in the lake’s high-alkaline waters (pH ~9) and grow faster than most other rainbow trout. These hardy fish have been successfully transplanted to other areas in California, Canada, and New Zealand.

A RICH FOOD WEB

The lake’s habitat supports a wide variety of aquatic species, contributing to its rich ecosystem and providing an abundance of food for the trout. The North and Central basins are full of tules and submerged weed beds, while the South basin has weed beds and porous volcanic rock. According to a DFW study, Eagle Lake trout diets consist of leeches (30 percent), snails and scuds (26 percent), and tui chub (12 percent). The rest of their diet (32 percent) was supplemented seasonally by chironomids, caddis, Callibaetis, damselflies, Hexagenia limbata, and daphnia. This bounty explains the trout’s rapid growth and the lake’s reputation for producing hefty, healthy fish.

WILDLIFE BEYOND FISH

The surrounding landscape makes Eagle Lake just as appealing to birders and nature lovers as it is to anglers. Bald eagles, ospreys, white pelicans, and grebes are regular visitors, joined by blue herons, cormorants, geese, ducks, and egrets. On land, deer, bears, mountain lions, bobcats, foxes, coyotes, raccoons, and otters contribute to the area’s vibrant ecosystem.

FISHING THE SEASONS

The fishing season runs from the Saturday before Memorial Day through the end of February. While October through February are the most productive months, anglers must be prepared for cold, sometimes extreme, conditions: icy roads, frozen boat ramps, and frigid winds. Layering clothing, packing hand and feet warmers, and a warm hat are essential. While fly fishing can be productive during the early summer, water temperatures rise quickly and trout retreat to deeper, cooler zones.

While there are many good shore access points around the lake, boat access can be more challenging. The Eagle Lake Marina at the south end is the most reliable launch, though water levels dictate whether Spaulding Tract’s facility is accessible.

TECHNIQUES AND TACTICS

When I first fished Eagle Lake, stillwater fly fishing was just starting to gain in popularity, and the go-to methods involved either:

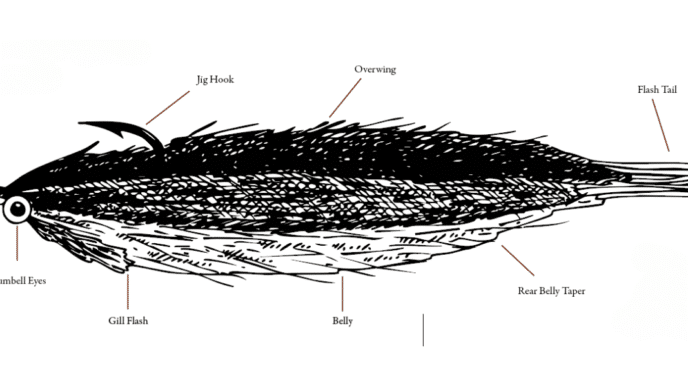

Intermediate or Type III sinking lines with a 9-foot 3X fluorocarbon tapered leader, often rigged with a #10 wiggle tail (leech) or #8 trolling fly tui chub imitation; or a #12 scud pattern with 20 inches of 3X fluorocarbon tippet and another smaller #14 scud pattern in a different color. Retrieval was slow hand-twists, with subtle strikes answered by a slight strip set.

Floating lines with 12-foot leaders, these were built using a 9-foot 3X fluorocarbon tapered leader and adding three feet of 3X tippet. Similar fly patterns and retrieve methods as with the intermediate lines were used. A dry fly with floatant applied was added to the end of our 12-foot leader if trout were rising to the surface. Strikes on dries required a brief pause before setting the hook.

A note on scuds: Their colors shift to match their surroundings—olive near tules and weed beds, tan or gray near rocks, brown or rust in mud. Dead scuds turn orange, and pregnant females carry an orange egg sac. Scud spawn year-round, so it is a good idea to have multiple colors and sizes, as well as multiple colors with egg sacks.

Fishing from a float tube or wading, I’ve found fishing around points, rock piles, and tules around 9–15 feet to be the sweet spot. Cast, let flies sink, then begin a slow, hand-twist retrieve. In a float tube, kick gently backward when starting your retrieve; wading, simply strip the flies back to you. Always pause near the end of your retrieve—many strikes come then.

EVOLVING METHODS

Stillwater tactics at Eagle Lake have evolved since my early years. In recent years, indicator nymphing from a boat, float tube, or wading has become increasingly popular and productive. Several years ago, my good friend and fellow guide Mark Antaramian introduced me to Phil Rowley and Brian Chan’s method of fly fishing stillwater—using a long leader with a midge and balanced leech suspended under an indicator. Electronics help pinpoint where the fish are in the water column, and how and what they’re feeding on, helping anglers set the depth of their indicators—about 2.5 feet off the bottom. Cast 15-20 feet out, letting your flies sink keeping tight with your indicator. Mend accordingly. Unlike tailwaters, in stillwater it is ok to move the indicator, giving the fly a swimming action. Strikes can be very subtle; any movement in the indicator warrants a hook set.

In recent years, Spey and switch rods have also become a popular choice among waders and shore anglers. This versatile option allows you to reach further distances from shore while wading. Lightweight, 3/4-weight 11–12.5 foot rods paired with floating heads for dry flies and indicators; a 10-foot intermediate or sink tip for streamers. The same leader builds apply for either technique.

For our leader we start with 18 inches of 17-pound monofilament, with a perfection loop at both ends. (A) Secure one end of the looped monofilament to the loop end of your floating fly line, this will be your butt section. (B) Next cut a 10-foot piece of 12-pound fluorocarbon and tie a perfection loop at one end. Attach that loop to the open loop of your butt section. (C) Slide on a large 1-inch hareline slip indicator. (D) Clinch knot on a small tippet ring at the end of your 12-pound fluorocarbon. (E) On your tippet ring, tie on three feet of 8-pound tippet, then clinch knot to the eye of your first fly. Your first fly will be the smallest of your two flies. Next clinch knot on another three feet of 8-pound tippet to the eye of your first fly. (F) At the bottom of that tippet use a loop knot to tie on a balanced leech.

A LAKE WORTH PROTECTING

Eagle Lake stands as a testament to the resilience of nature, offering a serene experience for those looking to connect with wildlife, enjoy fly fishing, or just appreciate the beauty of Northern California. Protecting this fishery through ongoing conservation ensures future generations will experience the same lessons and memories this lake continues to provide.