Should the name of the California Department of Fish and Game be changed to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife? That’s the question being discussed by legislators, top-level state executives, and wildlife activists as part of a move to overhaul the DFG. Most fly fishers may find changing the word “Game” to “ Wildlife” a real yawner. It’s not likely to stimulate heated discussion around the campfire, but it’s a barn burner of an issue among Sacramento bureaucrats.

The issue is generating heated behind-the-scenes debate because it’s part of a reform package to broaden the orientation of the DFG and its policy-setting parent, the California Fish and Game Commission. The debate is focusing on how the two organizations deal with so-called “hook-and-bullet” issues that appeal to the shrinking number of “consumptive users” (anglers and hunters) and the growing number of “non-consumptive users” (hikers, bird watchers, and others who don’t kill wildlife).

The complex reform discussion started over a year ago as part of a strategic “visioning process” that involved hundreds of stakeholders, public officials, and department staffers. They were was prodded into action by Assembly Bill 2376, which was introduced in the state legislature by Assembly Member Jared Huffman, D-San Rafael, an avid fly fisher who once worked for a conservation group.

“ The Department [of Fish and Game] is dysfunctional. It’s a mile wide and an inch deep and is structured in a way that makes it vulnerable to political influences,” Huffman told the press as the reason for sponsoring legislation that requires the state to develop a strategic vision for the DFG and the Fish and Game Commission. “I’m not doing this as a ‘beat up Fish and Game’ exercise. I am doing this because I care about Fish and Game. In order to make improvements, we need to shine some light on their failures.”

The visioning process, which included many hours of discussion of the failures of the DFG and the F&GC, was headed by an executive committee of high-ranking officials from the California Resource Agency, the parent of both the department and the commission. The committee was assisted by a designated Blue Ribbon Citizens Commission of attorneys, policy advisors, and former legislators and by a 54member Stakeholder Advisory Group that included representatives from such diverse groups as the Humane Society, Ducks Unlimited, the Audubon Society, the California Forestry Association, the California Farm Bureau, the Yurok and Karuk Tribes, and more. Sport-fishing groups included California Trout, Trout Unlimited, The Sportfishing Conservancy, and the Golden Gate Fishermen’s Association. One of members of the advisory group was Charles “Chuck” Bonham, who represented Trout Unlimited until he was appointed as the DFG director.

Problems Revealed

One of the first tasks in the visioning process was to shed some light on the problems affecting the DFG and the Fish and Game Commission. To do that, the vision planners interviewed 18 current and former employees and collected comments from 22 others in an online survey. According to a summary presented to the visioning group, here is what was said.

On changing the DFG’s mission: “For the most part, DFG is seen as a traditional hunting and fishing organization with an institutional culture not conducive to change. Furthermore, staff is typically perceived as ‘problem finders’ not ‘problem solvers.’

“Staff members see themselves as interacting with just 5 percent of the state’s population, instead of seeing themselves as trustees of fish and wildlife resources benefitting 100 percent of the population.

“The organization has not evolved quickly enough to meet the expectations of all users, which has fostered mistrust of DFG. There is frequently tension between biologists who manage a species for take and ecologists who support biodiversity.”

On regional policies: “Also, while acknowledging the diverse habitat in each of the seven regions, interviewees and survey respondents noted that DFG policy is not implemented consistently across the regions.”

On funding the department: “The overarching barrier to change . . . was funding. Interestingly, it was not lack of funding (though most acknowledged this as a major problem), but rather the tension between consumptive users and those who support nonconsumptive uses.

“That tension has resulted in creating dedicated funding sources. Not trusting DFG to fulfill its mission to support traditional hunting and fishing, respondents stated that past legislative efforts have tied funding sources to management of specific species. Currently, there are in excess of 40 dedicated funds. Instead of managing habitats for the benefit of resident species and all uses, DFG is legislatively constrained to expend efforts to manage specific species.

“There was a general recommendation that all wildlife would be better served by managing habitats to promote both consumptive and nonconsumptive uses. While consumptive users will likely not initially support license and tag funds being spent on habitat management, both species and users would benefit in the long-term from a diverse and sustainable ecosystem.

“All agreed that a stable funding source would be ideal. However, recognizing that limited resources are likely a fact of life for the foreseeable future, respondents indicated that combining dedicated funds would allow DFG to leverage resources and achieve economies of scale.”

On organizational culture: “DFG and F&GC are perceived as . . . a closed organization with little history of involving outsiders.

“Many interviewees observed that DFG is . . . more reactive than proactive. Priorities are said to be currently based on legislative mandates first, judicial directives second, and other mission critical discretionary activities third.

“Not all respondents agreed that these criteria for setting priorities served DFG well. Budget constraints and underfunded and unfunded mandates exacerbate the problem of setting priorities. The prioritization process is further compounded by the politics of competing constituencies.”

On the need for partnerships: “Other suggestions included leveraging partnerships with nonprofit organizations and public departments and agencies with overlapping responsibilities.”

On relationships with the legislature: “Any long-term change to DFG and F&GC will require legislative support. DFG is not seen as having a strong relationship with the legislature or legislative staff. It was pointed out that California State Senate and California State Assembly staff members do not enjoy free access to DFG employees, unlike they do with other departments and agencies. The DFG director needs to prioritize building a strong relationship with the legislature and legislative staff.”

On the Fish and Game Commission: “The current F&GC structure is seen as less than effective. Most thought the role of F&GC is important, but the structure is inadequate. The F&GC makes 40-50 rules a year — thought to be second in number only to the California Department of Food and Agriculture. Part-time commissioners don’t always have or take the time to research issues.

“While the interviewees were split on the proper number of F&GC members (recommendations varied from the current number of 5 to as high as 9), almost all thought members should be required to dedicate more time to the job — and be paid accordingly. Several interviewees and respondents commented on the need for F&GC members with more diverse backgrounds. Few supported the idea of a professional F&GC.”

On the likelihood of change: “Absent strong leadership by the director and commitment from the administration and legislature, it is highly unlikely DFG will change.”

Recommendations

Armed with this information, the visioning group made some the following recommendations for the DFG and the F&GC in its final report to the governor and legislature. (You can find the entire visioning group’s report at http://www.vision.ca.gov.)

On DFG culture: “DFG should create an internal culture that supports partnerships, encourages collaboration and promotes cooperation.

“Decisions made by managers and policymakers [should be] informed by credible science in a fully transparent process. “DFG must engage in outreach and dialogue that encourages the scientific community to address salient, timely management issues, while at the same time becoming more responsive and open to new ideas and emerging tools that could improve practices within DFG.”

On the name: After a limited debate, the visioning group decided to make no recommendation on whether to change the name of the department.

On DFG funding: “In the future, when the legislature enacts legislation, it [should] identify a specific means by which the new mandate is paid for.” It should also require “open and transparent accounting with DFG to build public confidence in how funds are managed.”

On endangered species: “Establish an inter-agency coordination process to ensure consistency and efficiency in the review of multiple permits, such as CESA [the California Endangered Species Act] incidental take permit applications, streambed alteration agreements, and other appropriate permits and agreements.

“Remove permitting barriers to ‘smallscale’ restoration and other appropriate projects.”

On game wardens: “Most environmental laws were not being adequately enforced by either DFG staff or wardens — to the detriment of fish, wildlife and plant resources. As the most visible enforcement arm, all agreed that wardens were understaffed, underpaid and handicapped by outdated technology.

“The current pay structure for game wardens is significantly lower than that of other California law enforcement agencies of similar size. Develop equitable pay and benefit formulas.

“Ensure successful recruitment and retention of California Fish and Game wardens.

“Minimize the need for secondary employment for existing game wardens.

“Establish a state wildlife crimes prosecutorial task force . . . to identify new approaches to shared and specialized adjudication of environmental/wildlife crimes.”

On committees: “Pursue a high-level task force that reviews and makes recommendations regarding F&GC and DFG funding and efficiencies.

“A stakeholder group should continue as an advisory body to DFG and F&GC.”

Implementing the Vision

Following release of the vision document, DFG Director Bonham started holding meetings to create a stakeholder group whose members would provide advice on implementing the recommendations in the vision report. The department has not yet released any information on that process or opportunities for public participation.

Some of the recommendations in the visioning document are being considered as bills that are working their way through the state legislature.

Authored by Assembly Member Jared Huffman, D-Santa Rosa, Assembly Bill 2402 was approved by the State Assembly and is under review by State Senate committees. If finally approved and signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown, AB-2402 would: change the name of the department to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife; authorize the department to spend up to $200,000 to write the strategic plan that implements recommendations in the vision report (the DFG adopted strategic plans in 1995 and 2006, and the Fish and Game Commission adopted one in 1998), and authorize the department to spend up to $100,000 to create an Environmental Crimes Task Force.

It would also require members of the public to purchase an entry pass to use department lands, make it easier for the department to enter into partnerships with nonprofit organizations, particularly for managing department-owned lands, and direct the department to make sure that fees it charges for its programs cover all the costs of managing them.

An early draft of AB-2402 contained a provision that shifted much of the work of protecting endangered species from the Fish and Game Commission to the new Department of Fish and Wildlife. In effect, this would have left setting fishing and hunting regulations as the Fish and Game Commission’s primary work. “We had suggested that some of the CESA be done by the department, rather than the commission,” said Assembly Member Huffman. “That proved to be very controversial and threatened to kill the bill, so it was dropped.”

According to the State Assembly bill analysis, AB-2402 is supported by the Audubon Society, the Endangered Habitats League, The Ocean Conservancy, and The Nature Conservancy. It is opposed by 14 agriculture groups, including the California Cattlemen’s Association, the California Farm Bureau Federation, and the California Grain and Feed Association. It is also opposed by the California Association for Recreational Fishing, the California Lobster and Trap Fishermen, the California Sea Urchin Commission, and the Point Conception Group Fishermen’s Association. No sport-fishing groups or flyfishing clubs have been listed as having taken a position on AB-2402.

Other bills that help implement the strategic vision recommendations include the following:

Senate Bill 252, introduced by Senator Juan Vargas, D-Chula Vista, would allow game wardens to join a union, making it easier to increase their wages and benefits. It was approved by the State Assembly and failed to gain passage in a Senate committee, but can be reconsidered.

Senate Bill 1107, introduced by Senator Tom Berryhill, R-Ripon, would allow groups that work on fish-and-wildlife issues to have their logos and website addresses added to the DFG’s new electronic system for purchasing fishing and hunting licenses. It was approved by the Senate and is pending in an Assembly committee. Assembly Bill 2283, introduced by Assembly Member Anthony Portantino, D-Pasadena, would change the DFG’s name to the California Department of Wildlife and allow use of the term “CAL WILD” to refer to the department. It has been approved by the Assembly and is under review by a Senate committee.

Assembly Bill 2609, introduced by Assembly Member Ben Hueso, D-Chula Vista, would establish qualifications for members of the Fish and Game Commission and create a “Code of Conduct.” It was approved by the Senate and is pending in an Assembly committee.

Senate Bill 1148, introduced by Senator Fran Pavley, D-Santa Monica, would require the DFG to maintain, rather than simply conduct, an inventory of all California trout streams and lakes, state a preference for native trout in stocking operations, require hatchery-produced fish to be marked whenever feasible, require all hatchery-produced fish stocked in California waters be sterile, require updating of the department’s Strategic Plan for Trout Management every five years, require the establishment of a Hatchery Independent Science Advisory Panel, and change the method that the DFG uses for setting license fees. It has been approved by the Senate and is pending in the Assembly. If the legislature fails to pass these bills, some of them will likely be reintroduced in the next legislative session, which begins in January 2013. You can check on status of the legislation at http://www.legislature.ca.gov/port-bilinfo.html.

Developing Political Muscle

Fly fishers and river conservation groups are making their mark at the State Capitol. After years of being criticized for not having lobbying juice on bills in the state legislature, the groups have been much more active, walking the halls advocating for fish and water and hosting flashy press events to get in the headlines. Trout Unlimited and California Trout recently held their annual “Casting Call” at the State Capitol, which featured lawmakers participating in a fly-casting contest. The Tuolumne River Trust and other river groups paddled their boats from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to Sacramento and then staged a demonstration over plans to divert water from the Delta, which they say will harm salmon and steelhead. And on a similar tack, the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance organized a demonstration to protest the announcement by Governor Jerry Brown and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar to push forward with plans to build a pair of pipes to divert water around the Delta.

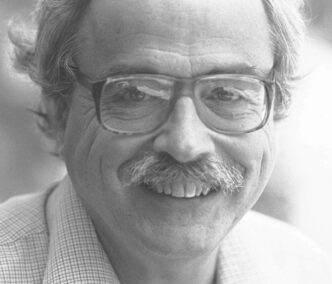

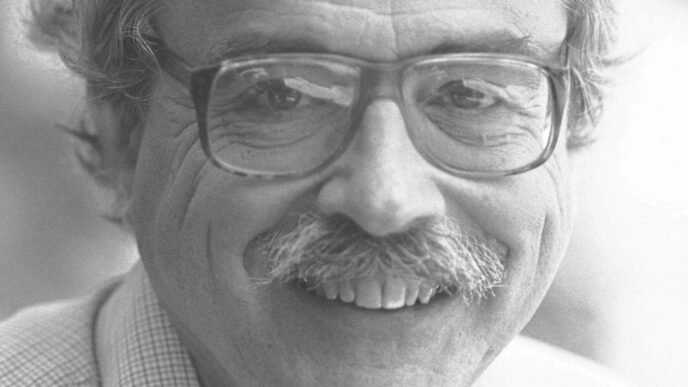

Tom Martens