Mercury and gold mining have gone hand in hand in the Sierra Nevada ever since the mid 1800s. The one is critical to the other, but their combination leaves a toxic legacy for game fish, which high-country anglers are eating at a risk to their own health.

These are some of the findings in studies by a small, but aggressive conservation group that has embarked on a campaign to increase awareness of the dangers of mercury in rivers and lakes, especially for anglers who eat the tainted fish or breathe in contaminated dust when hiking along trails to their favorite fishing spots.

“Where we live, this is a huge, huge problem,” said Elizabeth “Izzy” Martin of Nevada City, chief executive officer of the group that is raising alarms about the dangers of mercury. She heads The Sierra Fund, which bills itself as the “Community Foundation for the Sierra” and whose work includes an innovative blend of fundraising with advocacy.

Since starting work in 2001, the fund has assisted in generating more than $100 million in public and private funds for the Sierra, according to records of the nonprofit, tax-exempt group, and has made $1.5 million in grants to nonprofits to protect and restore natural resources.

“Advocacy is also a big part of what we do,” said Martin, who was a member of the Nevada County Board of Supervisors from 1999 to 2003. “At the fund, we do strategic campaigns.”

One of the first such campaigns was to successfully lobby the California State Legislature to create the seven-year-old Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state agency that is charged with protecting 25 million acres in 22 counties in the Sierra Nevada. The group also helped with funding for the Friends of Deer Creek and for the Sierra Cascade Land Trust Council, which coordinates public land acquisition in the mountain range made famous by John Muir and Ansel Adams.

The latest campaign by Martin’s group involves improving awareness of the problems with mercury and mining and advocating for extending the moratorium on suction dredging for gold, which the group claims spreads toxic mercury in streams and rivers. “The reason that we got into it as a campaign is because there is a giant problem that nobody is paying attention to,” said Martin, who works with two other staffers in a three-room office in downtown Nevada City. “There are lots of abandoned mines.”

Indeed, the California Department of Conservation reports that there are 47,000 abandoned mines in the state.

Many of these are old gold mines, the remnants of the Gold Rush era of the 1800s, when tons of gold were pulled from streams in the Sierra foothills and out of North Coast rivers, including the Klamath, Scott, Salmon, and others. These North Coast streams contain threatened or special-status species, including coho salmon, whose habitat must be protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Gold was found in California as early as 1775, but its discovery in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill set off the historic California Gold Rush. Seventeen years later, miners had created 5,000 miles of flumes, ditches, and canals to carry water to gold mining operations. In 1853 alone, 93 tons or 2.7 million troy ounces of gold were mined in the foothills of the Sierra.

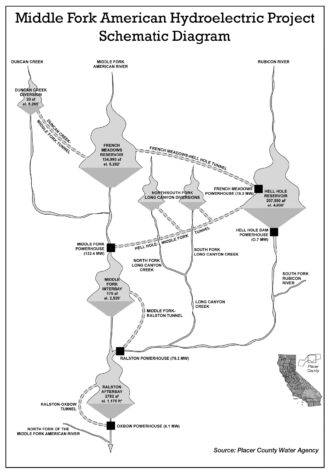

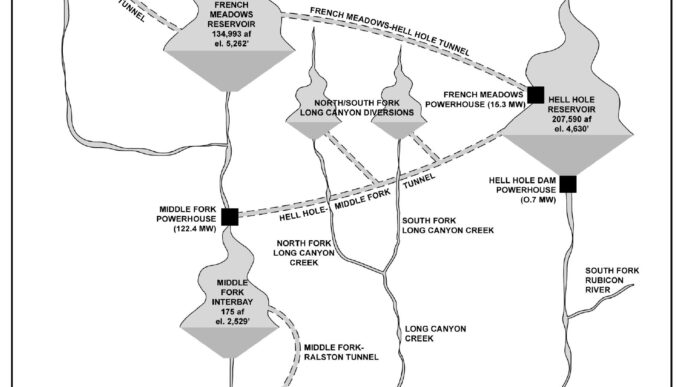

Fly fishers can easily see the remnants of the Gold Rush era in the state’s rivers, such as the forks of the American and Yuba Rivers and Deer and Bear Creeks in the Sierra foothills. Piles of rock and boulder tailings were created by the powerful water-pumping guns that were part of hydraulic mining. Riverbanks were carved away. Riparian vegetation was destroyed.

The Sierra Fund has published scientific studies, assessed the effects of abandoned mines and service roads on the health of recreational trail users, surveyed angler fish-eating habits, and quantified the relationship between mercury and current gold-dredging practices.

Some 26 million pounds of mercury was used in the Sierra as part of the gold mining process. The mercury binds with gold, and the increased weight allowed easier recovery of the gold, particularly gold contained in the liquid slurry created through hydraulic (placer) mining. An estimated 13 million pounds of mercury, however, were lost in mining processes. Some of this mercury remains bound to flecks of gold in the bottom of lakes and streams that are popular with anglers.

Mercury can be found in many California waters, but higher concentrations, largely a result of mining activities, exist in San Francisco Bay, the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta, and trapped in sediment behind dams and in foothill and North Coast rivers.

“On the periodic table, mercury is right next to gold, but it’s liquid at room temperature or at the bottom of a cold river,” said Martin. “It amalgamates with the gold, filling in the gaps in the shards and creating heavy blobs that sink to the bottom.”

And there they remain, except when disturbed by suction gold dredging or when they enter the food chain and get eaten by fish, which in turn are eaten by humans. “People are consuming locally caught sport fish from mercury-contaminated waterways in amounts that exceed safe levels,” concludes the fund’s recently completed Gold Country Angler Survey.

With the help of the Gold Country Fly Fishers in Nevada City and college interns, 151 anglers were interviewed in 2009 and 2010 on the American River and at Rollins, Englebright, and Wildwood Lakes and Upper Scotts Flat and Camp Far West Reservoirs. The fund’s 37-page report says that 90 percent of the anglers surveyed said they eat the trout or bass caught either by themselves or by someone else.

“Approximately half of the anglers interviewed planned to eat the fish they caught that day,” said the report. “Significant numbers of anglers (50 percent) feed the fish they catch to children under 18, women of childbearing age (54 percent) and, to a lesser extent, pregnant women in their household (6 percent). These groups are most at risk from the health impact of eating mercury contaminated fish.”

Catch-and-release-practicing fly fishers are not immune from ingesting mercury, which is breathed in when hiking along dusty roads and trails to favorite fishing spots in the Sierra foothills and along the North Coast — anyplace with historical or present-day gold mining activities. Many of these roads were built using mercury-laden rock and sand from the watersheds. Dust from unpaved Sierra roads is kicked up by vehicles driven by anglers, off-highway vehicles, mountain bikers, campers, and other recreationalists.

There is additional dust kicked up, so to speak, on behalf of some 3,000 suction-dredge gold miners in the halls of the State Capitol, where there is a lively debate about lifting or extending the two-year-old moratorium halting their work. The ban on gold dredging was put in place in order to give the California Department of Fish and Game time to write and analyze the environmental impact of permitting their operation. The ban applies only to suction dredging, in which divers use a hose in rivers, and not to shoreline techniques such as mining riverbanks with shovels or front-end loaders, use of sluice boxes above the water line, and gold panning.

The well-organized groups that defend suction dredging claim that there is no link between their work and mercury contamination in rivers. Martin says more research on the connection is needed, but anecdotal evidence leans in favor of a link. “It doesn’t seem like a coincidence to us that these places that have been suction-mined have really hot fish [fish that test with high levels of mercury],” she said. “We have evidence that suction dredging mobilizes mercury and makes it more reactive and able to methylate.” Methylation refers to the complex process by which solid chemicals get into the air — a transformation that results in highly toxic methylmercury.

“People are exposed to methylmercury almost entirely by eating contaminated fish and wildlife that are at the top of aquatic food chains,” states the U.S. Geological Survey’s website, which also notes:

The National Research Council, in its 2000 report on the toxicological effects of methylmercury, pointed out that the population at highest risk are the offspring of women who consume large amounts of fish and seafood. The report went on to estimate that more than 60,000 children are born each year at risk for adverse neurodevelopmental effects due to in-utero exposure to methylmercury. In its 1997 Mercury Study Report to Congress, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency concluded that mercury also may pose a risk to some adults and wildlife populations that consume large amounts of fish that are contaminated by mercury.

Martin and other environmental activists used the unproven, but suspected health hazards of suction gold dredging and methylmercury to convince state lawmakers to add language to the proposed 2011–12 state budget to extend the dredging moratorium for another five years or until the DFG produces sufficient regulations to mitigate all the impacts and create a fee structure to pay for all its suctiondredging program costs. Final approval of the extension of the ban depends on approval by Governor Jerry Brown of the huge budget bill or one of its follow-up funding cleanup bills, more commonly known as “trailer bills.” Martin said she expects the suction-dredging debate will continue through the summer and fall as part of discussion of one of the trailer bills or other legislation.

At issue will be how to prod the DFG into writing new suction-dredging regulations that keep all the influential and well-funded mining and environmental groups relatively happy and, most importantly, out of court. Martin says her group has developed recommendations for improving management of gold suction dredging. They urge increased collaboration on research, particularly focusing on the health effects of mining, the geographical distribution of mining toxins, mercury methylation, and effective cleanup and restoration techniques. They also recommend improved education about human health hazards through school programs, training health professionals, and public information campaigns. And they advocate the reform of government programs, including overhauling federal and state mining laws, creating funding for cleanups, changing suction-dredging laws, providing incentives for private land cleanups, and improving the disposal of recovered toxic materials.

The DFG’s suction-dredging rulemaking process has been a regulatory morass, the result of controversy, warring special-interest factions, and a fair number of lawsuits and court decisions. Gold dredging permits issued by the DFG increased dramatically from 3,961 in 1976 to a peak of 12,763 in 1980, reflecting the steep increase in gold prices in the 1970s. Gold prices have risen from $64 an ounce in 1973 to the price of $1,556 per ounce at this writing. The DFG has issued an average of 3,000 permits under its 1994 regulations, which were the subject of a successful legal challenge by the Karuk Tribe of California. In 2006, the court ordered the DFG to conduct a review of those regulations, their environmental impact, and the fees it was collecting to enforce them. Despite the court order, the DFG did not review or rewrite its regulations and kept issuing permits. In 2009, another lawsuit was filed, and the court prohibited the department from issuing any more permits while the litigation was pending. At the same time, the state legislature approved and Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed Senate Bill 670, which placed a moratorium on suction-dredge mining so the DFG could complete its court-ordered environmental review and adopt new regulations. That moratorium is set to expire at the end of this year.

In February, the DFG released its preliminary environmental review and its revised regulations for public review. According to the DFG’s Mark Stopher, who is managing the $1.5 million project, the department received comments from ten thousand individuals and groups, and some eight hundred attended six public hearings. Work has been halted on making changes and producing the final documents, because the current state budget did not provide money to complete the work.

As the budget issues were playing out, State Senator Ted Gaines (R-Roseville) introduced Senate Bill 657, which would repeal the suction-dredging ban, exempt the permits from review under the California Environmental Quality Act, direct the DFG to refund part of the permit fees to dredgers, and direct it to write an economic impact report (EIR) on the prohibition. “Legislative tricks are putting an entire industry at risk. This is unfair to the thousands of miners, their families and the businesses that depend on suction dredge mining for their livelihoods,” said Gaines in a press release. “This is maddening. The taxpayers have already spent more than a million dollars on a draft EIR. I don’t want to see a million dollars wasted, and I don’t want to see jobs killed off when we have 12 percent unemployment.”

Senate Bill 657 is supported by the Regional Council of Rural Counties and a timber company, but opposed by environmental groups, including the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, California Trout, Trout Unlimited, the Defenders of Wildlife, the Friends of the Trinity River, The Sierra Fund, the Sierra Club, the South Yuba River Citizen’s League, the Karuk Tribe, and others. Despite Senator Gaines’s passionate plea and heated testimony at a recent hearing, the Senate Natural Resources and Wildlife Committee killed Senate Bill 657, but ruled that the measure could be reconsidered in the future. That ruling for reconsideration means the debate over suction dredging, rivers, and trout will continue to provide fodder for hearings, press releases, and flyfishing-club conservation columns in newsletters well into the future. For more information on the gold suction-dredging issue, see The Sierra Fund’s website at http://www.sierrafund.org, the DFG information site at http://www.dfg.ca.gov/suctiondredge, and the U.S. Geological Survey’s fact sheet on mercury at factsheet/146-00. For a press release by a suction-dredging association, see http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases and use the search words “suction dredging.”