Watching fisheries that God nurtured over tens of thousands of years being virtually destroyed in less than two decades . . . is surely one of the most wretched and despicable spectacles we have ever witnessed.

— Bill Jennings

Bill Jennings is no shrinking violet when speaking up for sports fishing, and neither is longtime fish warrior John Beuttler or Chris Shutes, the fish-saving rookie of the bunch. This trio of environmental activists makes up the staff of the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance (CSPA), a lean and aggressive coalition of nearly 60 fly-fishing clubs, conservation groups, fishing businesses, and thousands of individuals. “We’re the guys in the trenches and don’t get a lot of publicity,” said Stockton’s Jennings, CSPA’s executive director. “ We work on complex issues with a long learning curve, but ones where fish will be saved or lost.”

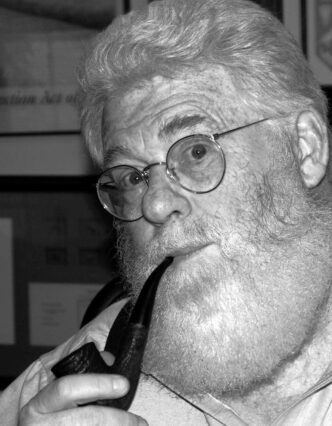

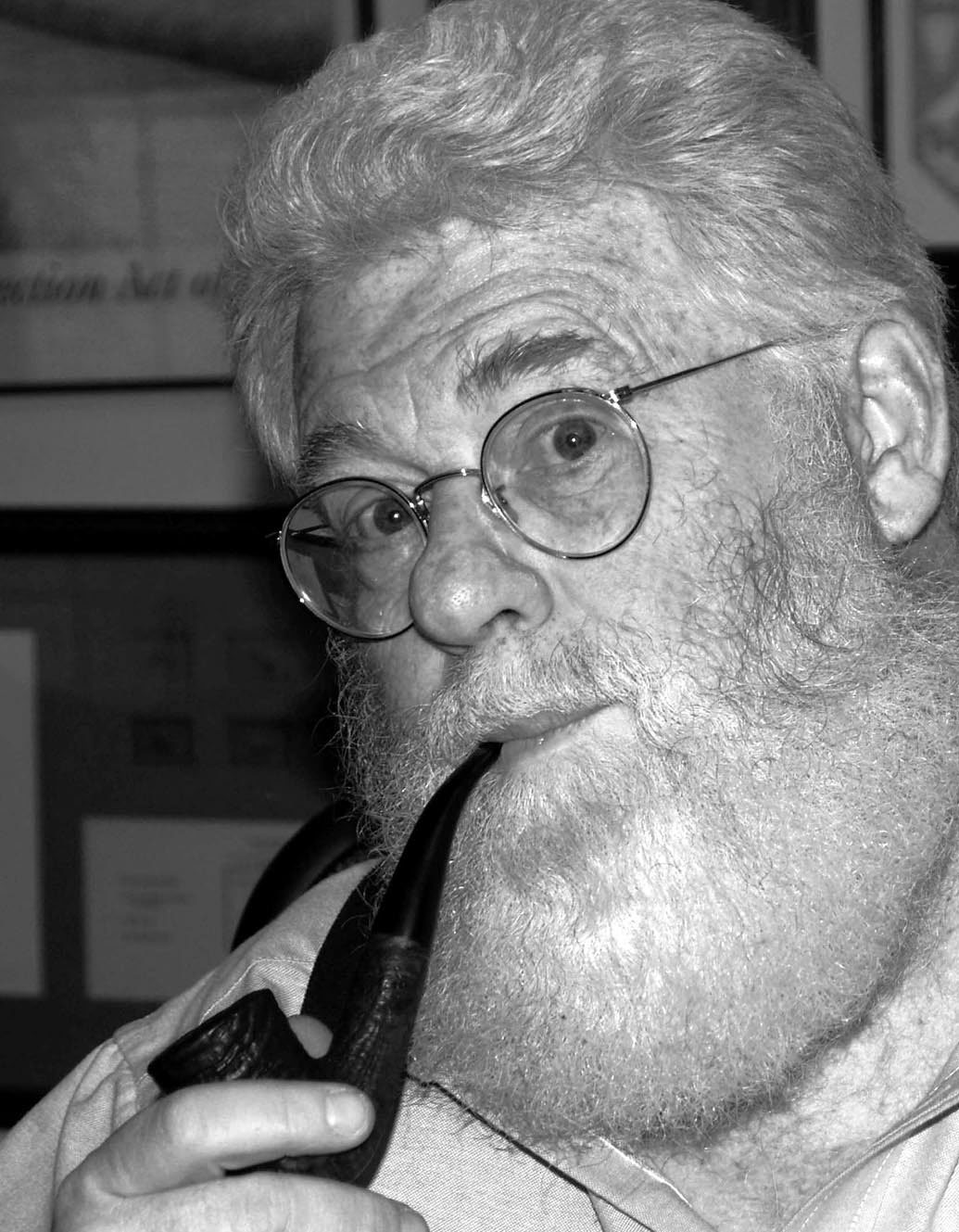

“Complex” is an understatement. When was the last time you filed an appeal complaint under a provision of the Clean Water Act to challenge the change in a sanitary district’s National Pollution Discharge Elimination Permit to allow increases potentially polluting discharges to surface waters from its “point sources”? Jennings will file a couple of appeals like this to the state water board before his pipe bowl runs out of tobacco. “We have about 50 appeals before the state board,” he said, referring to the California State Water Resources Control Board. “And we are taking about 20 enforcement actions and filing a number of lawsuits against agencies for failure to enforce the laws.”

He is referring to half a dozen strong environmental laws that are designed to protect water and rivers for fish. “If all the laws were complied with,” said Jennings, a white-bearded conservationist who resembles a pipe-smoking Santa Claus, “we wouldn’t have our fisheries collapsing.”

In recent years, California’s fisheries have been declining at an alarming rate.

The population of striped bass in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is near an all-time low. Runs of the fall, winter, and spring chinook salmon and steelhead are so low that the species are listed as threatened or endangered.

It’s this collapse that activists were trying to prevent when the nonprofit CSPA was created 27 years ago as the advocacy and litigation arm of fly-fishing clubs. The CSPA has grown to become one of the most effective fishery-protecting conservation groups by focusing on water rights, stream flows and water temperatures, hydropower dam relicensing, and issues in the state legislature. “There are probably eight thousand individual members who support our work,” said CSPA’s conservation director, John Beuttler of Berkeley, one of the founding directors of the group. “Our alliance of groups and individuals is very active on fishery issues.”

That was evident in early April when Beuttler sent out an action alert calling for CSPA supporters to oppose Assembly Bill 2336 at a public hearing before an Assembly Water, Parks and Wildlife Committee meeting in the legislature.

As drafted, AB-2336 recommended eliminating striped bass, a sport fish that is popular with fly anglers, from San Francisco Bay and from the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. “It is the intent of the legislation for the Delta Stewardship Council,” said the bill draft, referring to the newly created state agency charged with writing a long-range protection plan for the Delta, “to include in its final Delta Plan the identification of effective programs to discourage the promotion of the San Francisco Bay–San Joaquin River Delta as a striped bass sport fishery.” Language in AB-2336 also recommended that the council work to end immediately “any existing program for the enhancement, expansion, or improvement of striped bass populations and their habitat, and to eliminate any and all legal restrictions regarding the size and number of striped bass that may be taken.”

The measure was introduced in the legislature by State Assemblywoman Jean Fuller (R-Bakersfield), who has said it was needed to prevent striped bass from eating juvenile salmon and Delta smelt, species that are protected by the state and federal Endangered Species Acts. The bill was coauthored by Assemblyman Danny Gilmore (R-Hanford).

In a letter to the legislature and activists, Beuttler pointed out that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Delta Smelt Biological Opinion said there is no evidence that striped bass pose a significant threat to Delta smelt. “Studies of striped bass predation have found that they rarely, if ever, eat Delta smelt,” he said in the letter. “The predation that does occur to listed salmon is not in an amount that could affect salmon populations.”

With such explicit antistriper language in the draft bill, Beuttler had little trouble rallying his sport-fishing supporters to action. “I understand that the committee got hundreds of letters in opposition,” he said.

The day before the public hearing was to be held, Beuttler and others were informed that the bill’s author had “gutted” the measure, which means that an amendment would be introduced removing the striped bass eradicating language. The CSPA send e-mail alerts telling fish activists that they were no longer needed to testify at the hearing. However, because the amendment had not actually been added to the bill, many of the activists decided to attend the hearing anyway. “Some one hundred people showed up,” said Beuttler. “I was proud, because it wasn’t easy for many of them to go. They have jobs and commitments. Many of them testified and were counted and kept the bill from lowering the bar on fishery management standards.”

According to the legislative analysis of AB-2336, over a hundred individuals and 43 groups, which included 22 Northern California fly-fishing clubs, opposed the bill. The measure was supported by 24 water districts, agricultural associations, and business groups, including the influential California Chamber of Commerce.

Was this a victory for CSPA and the fish? Yes, but it may be only temporary.

By a 10-to-1 vote, the unamended version of AB-2336 was approved by the committee, which moves the measure ahead in the legislative process.

For the CSPA staff and volunteers, this means that the measure must be watched closely until the amendment changing it is added and to be sure that other antistriper changes are not added to the bill in the future.

Advocates for Fish

Beuttler said that serving as a watchdog over the state legislation was one of the two main reasons for CSPA being created in 1983. “After an assessment back then, it was our conclusion that the State of California was giving away water rights, and that was one of the biggest threats to fisheries,” said Beuttler. “Our other area of concern was that the state legislature was not a good trustee of the public’s fishery resources. It was a low priority with them.” Large conservation groups such as California Trout and Trout Unlimited did not make legislative lobbying a high priority. “There wasn’t anybody engaged in the legislature — or at best, it was someone’s part-time job,” said Beuttler. “There was no comprehensive understanding of the legislative agenda and few were making sure that good fish management was the principle for decisions.”

So three groups — the United Anglers of California, the California Striped Bass Association, and the Northern California Council of the Federation of Fly Fishers (NCCFFF) — started the CSPA to fill the void on water and legislative issues. The late Roy Haile, a Dunsmuir flyshop owner, was the CSPA’s first president. The group’s current president is Sacramento’s Jim Crenshaw, a longtime conservation activist and fly fisher. The membership of the CSPA’s current board of directors reads like a veritable Who’s Who of fly-fishing activists. Besides Jennings, Beuttler, and Crenshaw, the board includes Richard Izmirian of San Carlos, a longtime NCCFFF activist; Corey Cate, past president of the Tracy Fly Fishers; and Mike Jackson, an environmental lawyer from Quincy. For many years, the face of the CSPA was their staff member, Bob Baiocchi, who worked out of his home in Graegle in Plumas County.

Supporters and fly-fishing clubs raised money to support the CSPA through special events, including, until about five years ago, the NCCFFF’s dinners at its conclaves and Hall of Fame Award ceremonies. Currently, Beuttler said, money to support the CSPA’s efforts comes from individual donations, foundation grants, and some public-agency funds to pay for its long-running Suisun Creek Watershed Project.

The Suisun Creek watershed drains 53 square miles of Napa and Solano Counties. The creek runs from the City of Vallejo–owned Gordon Valley Dam through the picturesque Suisun Valley agricultural area just west of Fairfield and down to the Suisun Marsh. In 2004, the CSPA, the City of Vallejo, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and regional water-quality officials produced a plan for protecting and restoring the watershed.

“We got an agreement with the City of Vallejo dealing primarily with protecting flows and keeping water temperatures low,” said Beuttler. “Now we are working to repair the riparian canopy to keep the water cool for steelhead.”

The plan is touted as a model for “fish-friendly farming,” because it blends fishery conservation with agricultural practices (See http://www.fishfriendlyfarming.org/otherwatersheds/suisuncreek.html.) Under the innovative watershed program, ranches and vineyards can gain a Fish Friendly Farming certification for balancing their crop-raising operations with creek and watershed protection and restoration practices. Over a dozen have gained the certification.

The CSPA’s other advocacy work on behalf of fisheries can be friendly, as well, when consensus agreement is needed, or very unfriendly, particularly in issues where compromise is not possible. One of those issues is the CSPA’s opposition to the plans and funding for additional reservoirs and a canal to divert water around the Delta estuary. In November, state voters will decide on an $11.1 billion water bond, which will provide funding for dam and reservoir expansions and a project resembling the Peripheral Canal, which voters rejected in 1982. “No estuary in the world has been restored by diverting water around it,” said Jennings, who is gearing up for a fight over the canal before the State Water Resources Control Board. “Nothing can be done on the canal without a state board evidentiary hearing.” These often arcane hearings and proceedings are his specialty.

Using administrative and legal arguments, Jennings has successfully killed projects, changed permit conditions, won millions in environmental mitigation settlements, and amended river-flow regimes in ways that protect fish on nearly all the major rivers in the Central Valley. He works out of a small home office in Stockton that has book shelves jammed with water and fish studies and environmental reports, lawsuit settlements, and various technical reports. Many of these date back to his work from 1995 to 2005 as a Deltakeeper, which involved observing water polluters from a boat and then filing legal complaints to correct the problem. The winner of many conservation awards, Jennings is the founder of the Committee to Save the Mokelumne.

Water Rights and Dam Relicensing

Over in Berkeley, the CSPA’s Chris Shutes is leading the group’s effort dealing with the complex issues of protecting fish as the processes involved in approving water rights and relicensing the operations of privately owned dams under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) go forward. “We probably have a dozen water-rights protests right now,” said Shutes, referring to challenges to rights to use water from various sources and for a wide variety of purposes. “ We try to choose petitions or applications that relate to larger issues.”

Some of these include preserving water in rivers for fish, keeping surface water from being pumped into the ground at the expense of streams, removing fish-blocking barriers in rivers, requiring stream-flow gauges, protecting stream flows and water temperatures, and figuring out how much water is being used. “We try to get a thorough accounting of existing water,” said Shutes. “And then figure out the impacts.” If the CSPA decides that a water rights application will harm fish, often the organization must file a protest, which can sometimes have a short deadline. That process can lead to hearings, legal proceedings, and settlement negotiations to protect fish.

In addition, Shutes works on a similar appeal process for challenging conditions under which privately owned dams are licensed or relicensed, a process that happens only every 30 to 50 years. “The relicensing triggers a process of study by the resources agencies,” said Shutes. “And NGOs [nonprofit nongovernmental organizations such as the CSPA] have a substantial say in what happens.”

The CSPA is actively working on 10 dam relicensing processes, which deal with issues such as daily, monthly, or seasonal stream flows, water use for generating electricity and for recreation, water-temperature regimes, and operating dams in ways that protect fish. Shutes said that some of the rivers on which he is working on dam issues include the Yuba, McCloud, American, Feather, Mokelumne, and Merced, as well as Butte Creek.

Recently, the CSPA has been working to get rid of illegal diversions of water from rivers, particularly along the North Coast. “There are a lot of illegal diversions in that part of the world,” said Shutes. “The state water board is supposed to enforce the law on diversions, but they have not done a good job.”

In addition, the CSPA has worked to prevent diversions along the Central Coast. “We have been involved with overdiversions in the Carmel River,” said Shutes, referring to users diverting more water than allowed under permits. “We are also concerned about small diversions all up and down the Central Coast that have really played havoc with the remnant steelhead populations.” He said that work is limited by his time and available funding. That has been the CSPA’s story from the beginning — short on time and short on money for the intensive and detailed work of protecting fisheries. But what the CSPA lacks in funds, its staff makes up in tenacity. One developer once called the CSPA the “junkyard dogs” of the fishery advocacy community, according to Beuttler, who added: “I guess that’s true.”

Contact Information

Except for donations, all CSPA correspondence should be addressed to John Beuttler, California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, 1360 Neilson Street, Berkeley, CA, 94702-1116. Phone: (510) 526-4049; e-mail: jbeuttler@aol.com.

Donations should be sent to Mike McKenzie, California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, 6597 Cane Lane, Valley Springs, CA 95252.

The CSPA’s Web site is http://www.calsport.org.

Tom Martens