We tend to go to our grave naïve about certain subjects, whether on purpose or otherwise. I fully intended to meet my maker gleefully oblivious of the arcane, labyrinthine subject of hydropower facility licensing/relicensing under the aegis of FERC — an acronym (for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission) that strikes terror in the hearts of even the most courageous environmental warriors and anglers. Who has time for such frippery when there are fish to be stalked, fooled, caught, and released? Right?

Alas, my plan to remain oblivious went awry when I learned that a FERC relicensing process was afoot for the streams of my beloved Middle Fork of the American River, where the Placer County Water Agency (PCWA) owns and operates a multifaceted hydropower facility known as the Middle Fork Project. It’s funny how things change when a bogeyman makes a crash landing in your home water. No more excuses, no more “Let someone else do it.” It’s time to dust off those neglected analytic skills and dive in. And so I did, and I never looked back — until now, that is. In retrospect, it was an interesting, enriching (not to mention time-gobbling) collaborative process that resulted in some excellent long-term watershed and fishery improvements.

Dam relicensing is one of the main arenas in which fisheries and watershed conservation and improvement issues are now being contested, and for those just entering the fray, in what follows, I offer the testimony and lessons learned of one who has fought the good fight and has the scars to prove it. This is not a primer on the FERC relicensing process, but an abbreviated summary of that highly structured and complex process that I hope will help others understand when, where, and how it is most practical and productive to apply time and energy and to bring political and other pressure to bear as and if necessary.

For a detailed discussion of the licensing/relicensing process, you can access the Hydropower Reform Coalition’s excellent monograph Citizen Toolkit for Effective Participation in Hydropower Licensing at ide/hydropower-licensing/citizen-toolkitfor-effective-participation. Here, I’ll just sketch the main elements of the relicensing process, beginning with a brief discussion of what a “license” is and how the licensing system works, with some comments about how fisheries advocates can most effectively to participate in the process. Then I’ll discuss the specifics of the relicensing process that my allies and I went through for the hydropower project on the Middle Fork of the American and some of the other lessons we learned in the course of those negotiations.

The FERC Relicensing Process

The Hydropower Reform Coalition’s toolkit contains the following statement: “A license is a regulatory document that permits the dam owner to use public waters for energy generation. It specifies the conditions for construction, operation, and maintenance of the project. When final, a license is enforceable by FERC or the U.S. District Court through fines or injunction. FERC may revoke a license in the event of systematic non-compliance.” The license specifies its term — generally 30 to 50 years — and defines mandatory conditions under which the project may be operated. Conditions relevant to angling include minimum in-stream flows, reservoir levels, ramping rates, flushing flows, spawning flows, fish entrainment, and related matters. Normally, the license conditions also include requirements for recreation facilities such as campgrounds, river access, and perhaps trail construction and/or maintenance.

Dam licensees are required to initiate the relicensing process with a “Notice of Intent” to FERC no later than five years prior to expiration of their existing license. Most licensees begin the process and hire the necessary technical consultants before that deadline, primarily due to the huge volume of studies that must be designed, completed, and approved. They then prepare a “Pre-Application Document,” along with a study plan.

As will be clear throughout, the consultants hired by the licensee play a major role in the relicensing process. It is the licensee’s consultants who will produce the dozens of studies, including those on fish populations, in-stream flows, macroinvertebrate types and distribution, and other matters related to aquatic life. Their consultants also prepare recreation plans, mitigation and monitoring plans, and other related plans, all of which are of major importance, because the renewed license will likely last for 50 years.

Angling interests therefore need to determine whether and to what extent the consultants selected are objective in their analyses and reports. If the consultants’ work product is simply reflective of the licensee’s desired outcome (which was clearly not the case in the Middle Fork relicensing), it is incumbent on angling groups to produce countervailing evidence and to place it into the FERC record. If it appears that the consultants are being less than objective, discuss that issue with the licensee and the consultant — privately, to avoid embarrassing anyone publicly, including yourself.

It’s also important that fisheries advocates participate in the study design process, because how the studies are designed will have a major effect on their outcome. Parties participating in the process also are allowed to file their own studies and evidence if there is a conflict with the licensee’s studies. FERC manages the entire study process closely, with performance-related dates that are strictly enforced. Requests for time extensions are rarely granted.

At a later point, when all required studies are complete, the dam licensee files a “Draft License Application” with FERC. This is a highly structured document governed by FERC regulations, with evidentiary requirements and other procedural strictures.

There are three types of relicensing procedures for approving the relicensing application, but FERC has specified that the one called the “Integrated Licensing Process” is its preferred methodology, and deviations from that policy are discouraged. While it is complicated, this process is collaborative — it is designed to lead to a consensus-based settlement of all issues between the licensee and the other parties to the proceeding. This was the process successfully used in the Middle Fork relicensing process.

The Integrated Licensing Process is a negotiation. Negotiate in good faith, but from a position of strength, basing your approach on the angling interests and the science. Be ready to make reasonable compromises — no one gets everything they want. Aside from the licensee, the other stakeholders in this negotiation can include state and federal wildlife and water management agencies; nongovernmental agencies (NGOs), a category that includes interest groups such as anglers, whitewater enthusiasts and businesses, and conservation organizations; and individuals representing various other interests. As part of the collaborative process, at the outset, the various parties each prepare a document defining their respective interests. For example, angling and fisheries representatives specify their interests in preserving and enhancing fisheries, macroinvertebrate populations, watershed management, and similar matters. This document forms the basis for negotiations over how the various interests can be reconciled and addressed in the process. As you’ll see, we learned to our chagrin that it’s important to define the angling interests specifically in writing at the outset of the proceedings and to select knowledgeable, experienced anglers to speak for those interests.

Of major importance to advocates for angling interests also is the issue of which agencies have the power under federal law to impose mandatory conditions on the license and which have nonmandatory conditioning authority. In a nutshell, the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management (and a few other federal agencies) are empowered to impose mandatory conditions; the Department of Fish and Game has authority to elaborate nonmandatory conditions (however, because the DFG is normally supported by federal agencies having mandatory conditioning authority, the DFG’s suggested conditions are given significant weight); and NGOs and individuals have no conditioning authority, only negotiating leverage. By virtue of an interesting legal construct, the State Water Resources Control Board also has the authority to impose mandatory conditions relating to water quality, a very broad authority that affects fish and all aquatic life, because it is the agency designated by the federal government to implement the federal Clean Water Act within the state. This agency is generally “fish friendly,” as are the federal agencies and the DFG. Use every effort to garner the support of the federal and state agencies for your list of wants; conversely, support them whenever feasible.

During the collaborative process, draft studies are reviewed by all of the parties, meetings are held to discuss and clarify the studies, and negotiations occur over disputed issues. Insist on structured review of draft studies — but always come to meetings about them prepared and with an open mind. Comments on the studies should be based on the science, and not conjecture and opinion. Anecdotal evidence is good for the record, but it should be thorough and documented.

The consultant is heavily involved in all of these procedures, but because the studies are numerous and highly technical, angling representatives need to choose carefully which studies are required reading and which can be left to other interests. This is simply a matter of economies of time and energy and of strategy: the identification of critical issues. Once such priorities are set, attend as many of the crucial meetings as possible and use caucuses (among your team and with the other NGOs and federal and state agencies, as appropriate) to vet issues and develop joint responses.

The Middle Fork Project and Its Relicensing Process

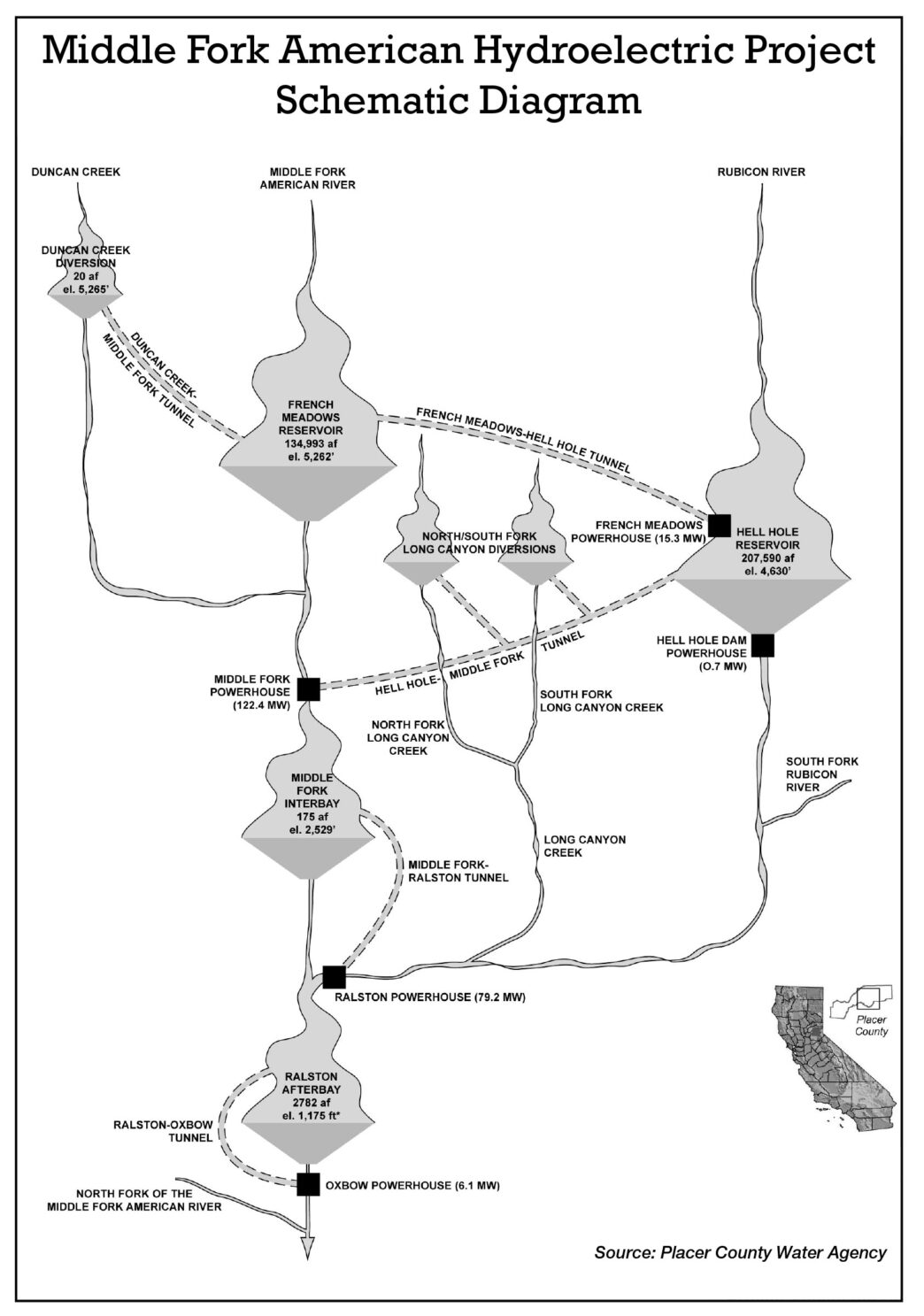

The drainage of the Middle Fork of the American River is controlled by the complex system of dams, afterbays, and other facilities that make up the Placer County Water Agency’s Middle Fork Project. (See illustration. A detailed text description of the MFP is available at Sum/ExecSumProjectDescription.pdf.) These facilities include French Meadows Reservoir, which traps the upper Middle

Fork and several other small streams; Hell Hole Reservoir, which traps the upper Rubicon River and other creeks; and a network of passive diversion tunnels, diversion dams, afterbays, and penstocks that generate power as Middle Fork water flows from French Meadows down to join the main stem of the American River.

The Placer County Water Agency’s 50-year hydropower license for this complex expires on March 13, 2013, having been issued by FERC back on March 13, 1963. Most of the project’s facilities were built in the succeeding three years — but not without problems. During the winter of 1964, major storms deposited huge amounts of snow in the Sierra. In December 1964, a “pineapple express” storm caused high runoff from snowmelt. Hell Hole Dam was under construction at the time, with the unreinforced earthen dam nearly complete. The extraordinary amount of runoff quickly filled the reservoir and undermined the incomplete dam, causing it to fail. The failure dispatched an enormously destructive wall of water down the narrow canyon of the Rubicon River. After a long period of lawsuits and finger-pointing, Hell Hole was completed in 1966, as were most of the other Middle Fork Project facilities.

In 2005, the Placer County Water Agency’s board of directors determined that the agency would utilize FERC’s collaborative Integrated Licensing Process for the MFP’s relicensing. To implement the board’s policy, during 2005 and 2006, the PCWA and its main consultant, Entrix, began early gathering of environmental and other information that would be needed to draft what is known as a “Preliminary Application Document” (PAD). In 2006, a collaborative process was instituted to design the study plan for inclusion in the PAD. “Technical Working Groups” were formed for this purpose, each group having expertise in specific disciplines. The result was a list of studies, each with a specific plan and time line for completion. Stakeholder meetings were held to identify all of the interests and representatives of those interests, and the identified interest groups became part of a “plenary” group that held regular meetings through 2007.

The Notice of Intent, which formally initiates the FERC process, along with the PAD, was filed on December 13, 2007. During 2008–2009 and into 2010, the study plan was implemented, studies were conducted, and draft study reports were prepared for collaborative review — all of which took a long time. (The entire formal schedule for the MFP relicensing can be viewed at html/whatis/relicensingschedule.php.)

In a very wise move, the PCWA hired a “facilitator” consultant, in addition to the consultant in charge of implementing the required studies. This person was skilled in multifaceted projects, including those of FERC, where many different interests (sometimes conflicting) are involved. In the plenary meetings and later in the negotiations phase, this person’s function (which she performed admirably) was to be strictly neutral, keep the meeting focused on the agenda, keep the discussion relevant, adhere to the timelines on the agenda, and defuse potentially explosive disagreements. In other words, she was very skilled at herding cats.

Lessons and Results

One of the principal lessons we learned in the relicensing process for the Middle Fork Project is that it is important that the angling interest be clearly articulated from the outset of the proceedings and that individuals and groups be identified in the record as representing that interest. We did not do this properly — simply because we were not familiar enough with the process and the implications of dropping the ball on this point.

In 2006, the consultant arranged a work session with a group of anglers, including me. I was unable to attend the meeting because of prior commitments, but the consultant’s representative interviewed a small group of fly fishers. Unfortunately, the information elicited was not specific, and the consultant’s representative simply did not understand what is and is not important to anglers. When the consultant’s summary of the meeting was issued, it was incomplete and contained significant misinformation.

During the review process for the draft study, we continually insisted that the studies pertinent to angling were in error because of the cursory 2006 meeting and report. As a result, a much more structured and comprehensive meeting was held in 2010, and the information gathered there found its way into revised draft reports.

Had we been better organized at the outset and had we realized the major “downstream” effects of the initial stakeholder meeting on the study results, we would have done things much differently. Persistence paid off, however, and the problem was resolved collaboratively.

Another major lesson that we learned while participating in the relicensing process was that we needed to seek outside support in order to achieve more clout in the proceedings, and in 2009, we formed a nonprofit corporation named the Foothill Angler Coalition. We sought and obtained written support from major national organizations, including Trout Unlimited and the Federation of Fly Fishers. California Trout joined our list of supporters, as did the Northern California Council of the Federation of Fly Fishers. Numerous fly-fishing clubs also joined the list, as well as major industry manufacturers. We were able, by taking this step, to demonstrate to the licensee and consultant team that our support included many thousands of fly anglers — and the licensee and consultant began listening closely to what we had to say. By marshalling outside support, we went from being a marginalized interest to a major force among the NGOs.

Staying focused on the issues most relevant to the angling interests also helped. The Middle Fork Project is a complicated facility, and the studies produced during the relicensing process reflected this complexity. For purposes of the study plan, the Middle Fork Project was divided into two logical physical pieces: The “peaking reach,” meaning everything below Oxbow Dam, where the river’s flow was radically increased and decreased during the course of the day, and the “bypass reaches,” which were all of the streams above Ralston Afterbay that had project facilities located on them, but where no “peaking” occurs.

The study plan called for a total of 34 scientific studies. When completed, these studies, together with their exhibits and appendices, occupy approximately 15 feet of shelf space. Obviously, it would be virtually impossible to review all of these thoroughly, so as I suggested above is necessary, we chose those most relevant to the angling interest: in-stream flows, fish population, macroinvertebrates, water temperature, bioenergetics, fish passage, fish entrainment, water quality, and stream-based recreation. While this is still a heavy load, we were able to read and comment on all of the relevant studies, because the consultant and the licensee conducted numerous meetings to explain and review the studies with all of the interests. This proved to be extremely helpful and was instrumental in the successful negotiations that followed.

After completion and review of the studies, negotiations began in earnest. The negotiations were “interest based,” an approach in which the parties attempt to come to consensus on issues based on meeting the expressed interests to the extent that doing so is reasonable and feasible. This differs from other negotiation processes (endless proposals, counterproposals, and so on) and is designed to facilitate collaboration and consensus.

In this negotiation process, we learned that when consensus is reached, it’s important to ask for a clear iteration of all of the points agreed upon and reduce them to a list of “deal points.” If consensus cannot be reached on a critical issue, it is wise to “table” the issue and come back to it again at a later time. When the time comes to pen a “package,” you may be able to gain ground on the issue if it is important to the licensee (and it will be) to achieve full agreement on all issues.

While the process was drawn out and required compromise by all parties, it resulted in significant gains for the fishery and watershed. To list all of them on each of the affected streams is beyond the scope of this article, but a few of the significant fishery benefits for the bypass reaches were: significantly increased minimum flows; periodic “flushing” flows to mimic the natural flushing that occurred in all of the canyon’s streams before the project was built; increased flows during the rainbow trout spring spawning period for increased spawning habitat and cooler water; facilities modification to reduce or eliminate fish entrainment; improvements to certain access trails and construction of a new access trail in the upper Middle Fork area; and a more reasonable approach to cessation of diversions into the three passive diversion facilities. For the peaking reach, some of the more significant fish and bug benefits were moderation of the ramping rates to prevent stranding of young fish and aquatic insects; stable flows during the winter period so that the lower river works more like a tailwater; and funding for construction of spawning facilities on the peaking reach.

These consensus-based fishery and watershed improvements were made possible by three main factors: The openness of the PCWA to environmental improvements that still provide operational flexibility and optimize power production, the collaborative nature of the consensus-based process, and the excellent, objective science generated by Entrix, PCWA’s consulting science firm.

Our experience suggests that advocates for the health of fisheries in the FERC dam licensing process can participate and negotiate effectively, at least when all parties, including the licensee, their consultants, and the other interests involved engage in the collaborative, consensus-oriented FERC Integrated Licensing Process in good faith. It ain’t simple, it ain’t fast, and it ain’t easy, but it can be made to work.