I don’t get the job.

It feels like an insult, a renouncement, a dismissal of the One Big Thing I’ve tried to accomplish in my life.

Who could possibly be more qualified than I am?

It feels like a big fish that got away, a once-in-a-lifetime cast tangled in the trees — the only meaningful response to which remains, as always, the same.

Oh, well.

Or . . . keep fishing.

Here’s a remarkable notion: I doubt two in twenty readers descending into this ditty couldn’t find themselves on a pretty good piece of water within, say, an hour’s drive from home if they felt they just needed to go fishing right now. And maybe it’s really only two out of a hundred of you who, for reasons I’d rather not contemplate, live beyond this realm of access and ready possibility. And yet how many of us, who claim we love this sport as we do, took the time to reach that water today, yesterday, this week, last week, the entire past month?

Please: I don’t need a show of hands.

But we should all ask ourselves: What are we waiting for?

Now, believe me, I know what happens. I understand the host of reasons and extenuating circumstances that keep getting in the way, that keep us off that “pretty good piece of water” that we don’t fish as much as we’d like to — or even as much as we could.

I get it. I really do.

But I’m sorry, I sort of don’t buy it.

What I’ve noticed, more of late than ever, is the number of fly anglers who seem always about to go fishing, who are getting ready for the next big adventure or reminiscing about one that just passed, and yet who, from what I can tell, overlook completely the sport available in their own literal or metaphorical backyards.

Or — and this might be the deeper issue — perhaps we are more interested in thinking about and planning fishing trips than we are about actually figuring out how to catch the fish we happen to have in our own humble lives.

Or maybe I’m just talking about me.

Eagle Creek lies halfway between town and the city. Don’t confuse it with Eagle Point, Eagle Lake, or the slough, beach, bay, river, park, and paddling pond with Eagle in its name. Eagle Something or Other could very well be that pretty good piece of water near where you happen to live. Look around. Doesn’t everybody have somewhere Eagle-like he or she could visit today?

The mouth of my Eagle Creek is reached by a twenty-mile drive on a freeway. That alone should tell you I’m not talking about a secret drainage at the far boundary a wilderness high in the Sierra. On a hot afternoon on the first week of summer, I have to circle the parking lot twice before I find a space, one that appears to be legal, or else five other vehicles stand to get ticketed, too.

Hikers and bathers make their way on and off the foot of the trail. So much in modern fly fishing involves “getting away” that we readily forget sport angling was once very much a social affair, practiced in the company of others whom we were glad to see on the water, if only because there was plenty of fish to go around and we recognized, just as we do today, that meaning is created through stories, that the connections we make through a shared point of view keep us from feeling alone in the shadows of the empty cosmos.

By all evidence, I’m the only angler on the busy trail today. In fact, I’ve never seen any other anglers but my own occasional companions on the water where I’m headed above a pair of upstream falls. Still, as I hurry in the heat along the wide and crowded trail, I’m frequently interrupted by someone who asks about the contents of the rod tube I carry — while just as often, I slide past someone else who glances at me and my gear with a gleam of sudden recognition, a look that reveals the delight and immediate envy of the idle angler who senses sport afoot nearby.

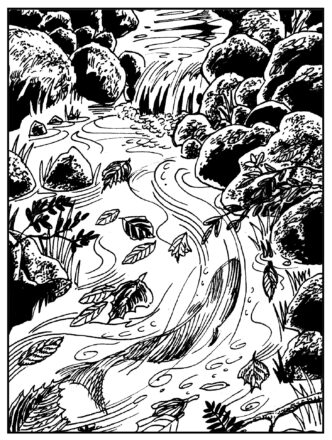

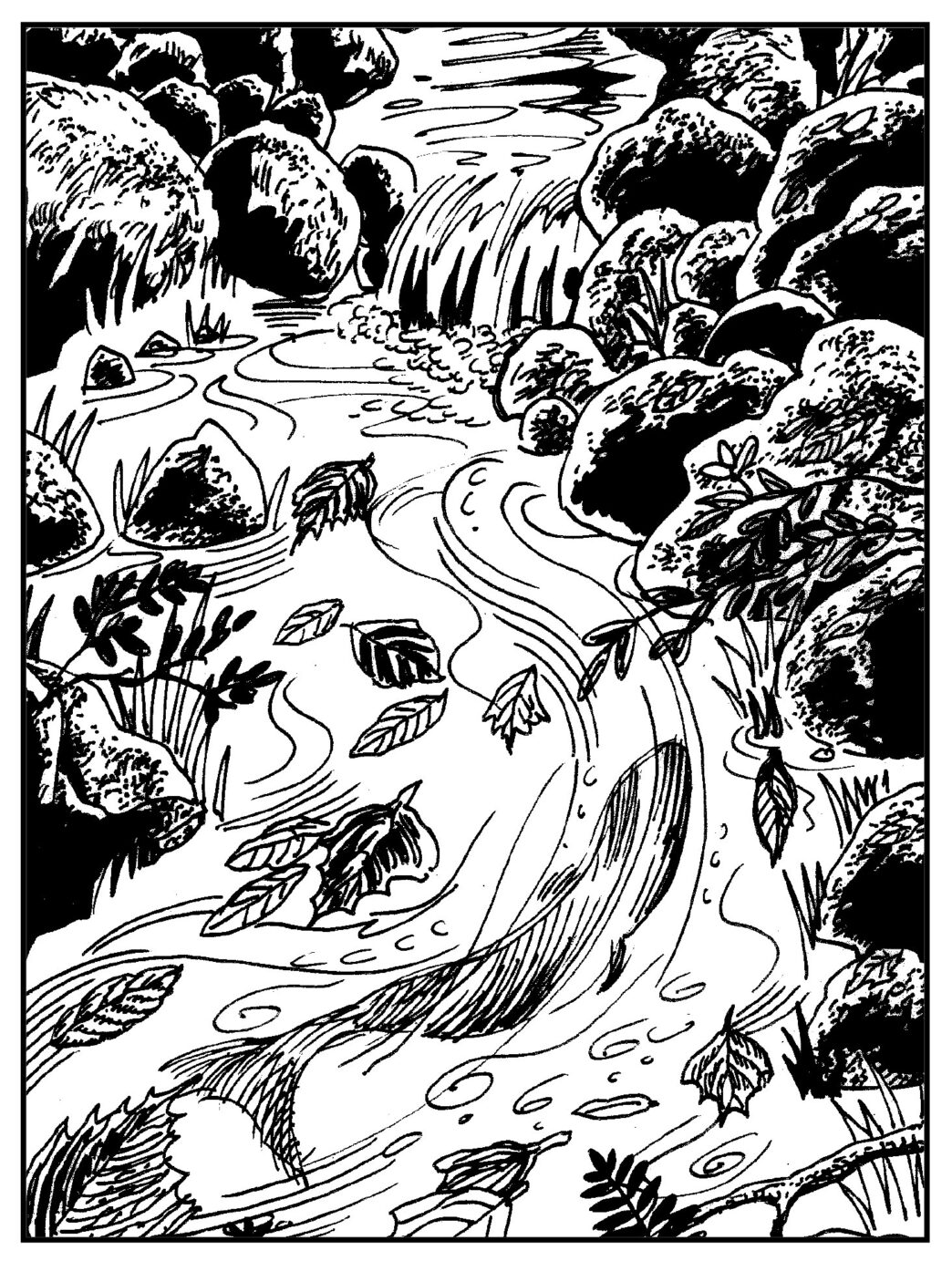

The trail traces the contours of a forested wall that plunges all but vertically through shade and thicket to the creek below. I look out over the canyon into the crowns of first rising two hundred feet from the pinched and hidden shadows hovering above the floor. The sound of the stream filters up through the trees as though a heavy wind barking at patches of sunlight. Here and there I can see the water — a dark ribbon frayed white with foam in its furious rush to weave its way out of the gorge.

Clusters of bathers head to and from plunge pools cupped beneath the roar of the falls. Wide paths descend through the trees toward laughter and playful squealing. But farther up the canyon, I find nothing obvious leading down to the creek, at best an opening through the vine maples created by a fallen fir or a sunlit outflow of jumbled basalt and scree.

Experience tells me it won’t matter, as far as the fishing goes, where I drop in — as long as I can find a way safely down to the streambed. The steep descent through brush and deadfalls and uneven footing proves only half the problem. The creek, having risen a dozen vertical feet during heavy spring rains, has carved away the soil at the base of the canyon walls, leaving behind sheer, polished bedrock between the vegetation and the retreating stream.

Scrambling down to the water’s edge, I sink into a pool of cool air, redolent with the scent of moss and maidenhair ferns, the punky smell of rotting timber jammed between truck-sized boulders. Above me, I hear voices from the trail — yet the scene here is entirely my own: private, remote, as wild as a mountain ridge.

Stringing up my rod, I’m reminded of beaches I fished when young, the riveting excitement of casting flies into what felt then like unexplored surf, the primordial tide of the sport rising unbeknownst to all but a few creative or wild-eyed anglers haunting the edges of beaches that millions and millions of Southlanders called home. What an audacious idea. Like early explorers, we knew little more than that the Earth is round, believing then that what was possible in Wyoming — or Key West, or Chesapeake Bay — was somehow also possible in these pockets of wild surf no more tameable than the sea itself. How lucky was that? Who could have imagined, just twenty-five years later, more than fifty fly fishers lined up along a stretch of San Diego’s Mission Beach for the annual One Surf Fly competition, a collection of fly casters as diverse as the California culture that has spawned so many rich and reckless ideas — some sporting, some not — over the course of the fly-fishing history of the West?

The trout, when I find some, are tucked alongside a boulder, big as a one-car garage, that has choked the stream into a heavy, deep run just before it breaks apart into a tangle of misdirected plunge pools, all of which seem to replicate perfectly the obvious holding water upstream. I miss the first few fish, either because my fly is too large or the fish too small — or because the stream really is higher than

I’m used to seeing it, and I can’t seem to get a long enough drift to give the fish time to rise and eat the fly.

I finally get one to hand, but not before I’ve switched to a smaller fly, broken another one off in a tree, and slipped from a rock and gone into the creek deep enough that it carries me a couple of heartbeats downstream. That helps focus my attention. I pull off my vest and open three different fly boxes to let the contents dry, keeping only a box of Humpies with me, the only pattern — in three different colors and four different sizes — I practically ever use on this water.

The trout are all wild, either cutthroats or rainbows. I sometimes fail to look closely enough to tell which as I free them carefully from the hook and slide them back into the creek. Of course, they all seem as lovely as tropical songbirds, their markings as sharp as colors cast through the prism of a lover’s eyes. Twice I see something that looks like a bigger fish, but both times it fails to eat for any or all of the reasons that rising trout refuse to take a fly.

I cross the stream, surprised how deep it is when I wade between the big boulders in the heaviest part of the current. My leather boots and canvas hiking shorts are not exactly high-tech wading gear, but by letting my feet slide down into the creases while leaning a knee or hip against the face of a rock, I manage to reach the other side without any more tremors inside my chest.

I understand now that this is where I should have started. I tie on a bigger Humpy, figuring at this point I’ll either move a better fish or get nothing more. I creep up close and drop the fly just inside the swing of the current. I get a long, steady drift. Then I see the trout a foot or so below the fly, rising toward the surface with that slow, deliberate lift that says As long as that bug doesn’t do anything weird, I’m going to eat it.

The distance I’ll travel to fool a twelve-inch trout has often seemed extreme. Even this close to home, it can feel like a long trip getting there. That’s probably another reason why some guys give up fishing near where they live. What do you prove with so little to show for doing so much? What’s the point, really, in getting so good — and sometimes lucky — in a skill that doesn’t seem to make a lot of difference to anyone else, that certainly doesn’t produce a tangible product that a boss will pay you a wage to produce?

By the time I bring the fish to hand, I have a pretty good idea why I was lucky enough not to get that job.