I’m sitting in a cabin on the crest of a ridge high in the coastal mountains of Northern California’s Mendocino County. The land is densely wooded with a fairyland mixture of oak, madrone, manzanita, redwood, pine, fir, and a practically impenetrable tangle of underbrush. It is essentially a wilderness, enormous, mostly trackless, and steep enough to defy all but the most obdurate and physically fit.

Eagles, vultures, and several kinds of hawks bank and float on the complex thermals, while beneath them, surprising flocks of band-tailed pigeons veer crazily into the treetops to feed on the abundant, bright-red madrone berries. Woodpeckers are ubiquitous, as are valley and the even rarer mountain quail. Jays squawk above them, while throughout the seasons, an ever-changing cast of songbirds nest, zip, and flit through the impossible network of leaves and branches.

Mostly safe from armed woodsmen, coast blacktail deer skillfully negotiate the steep, forested slopes, always clearly within earshot of hundreds of coyotes, which begin their high-pitched conversations at dusk. Foxes glide along, slunk low to the ground, as raccoons and opossums crouch undercover. And then come the legions of rude, snuffling wild boar, oblivious to obstacles, noses in the damp ground, plowing it for anything edible. In season, this would be the exquisite boletus and anything else digestible.

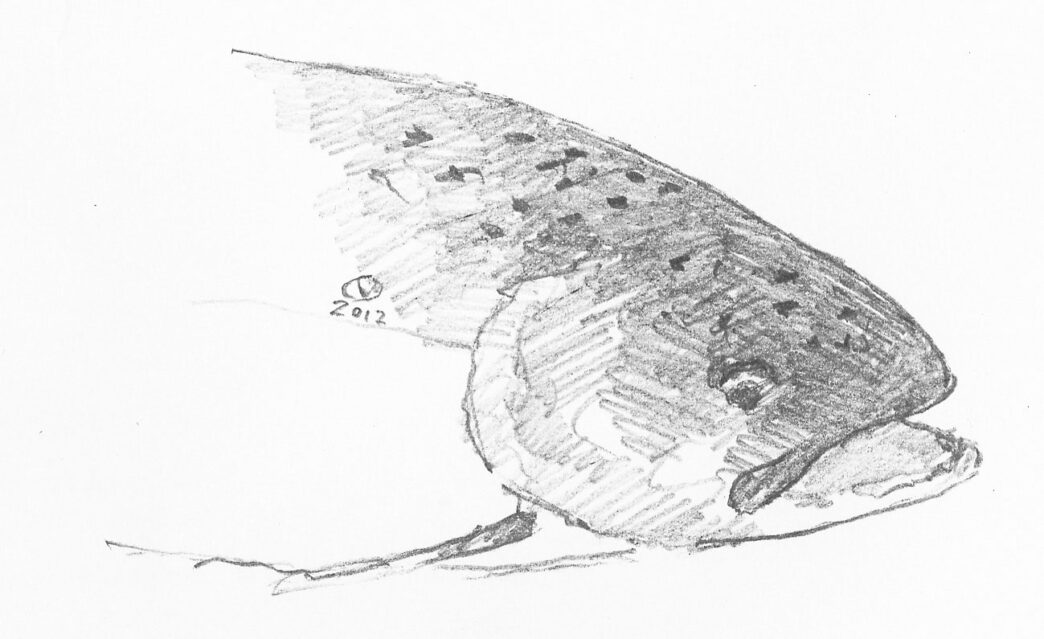

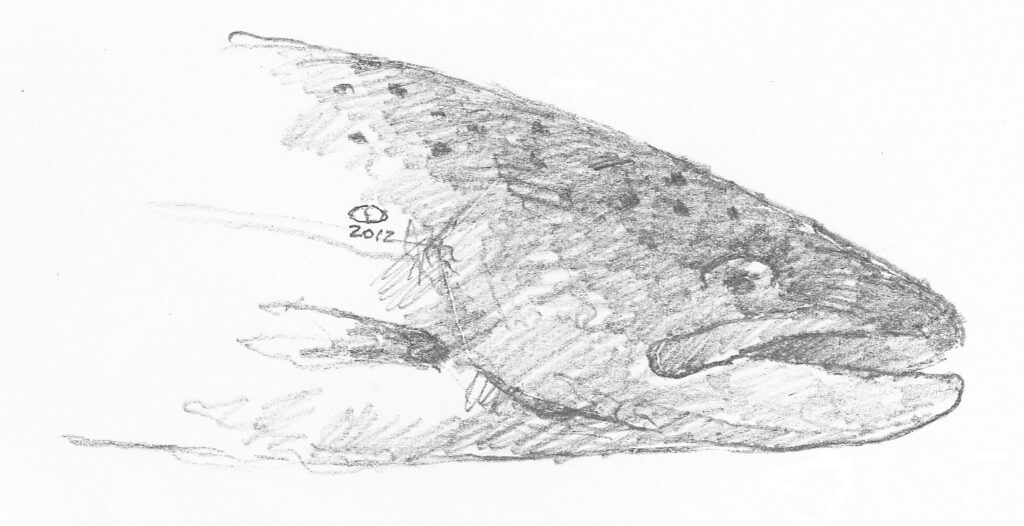

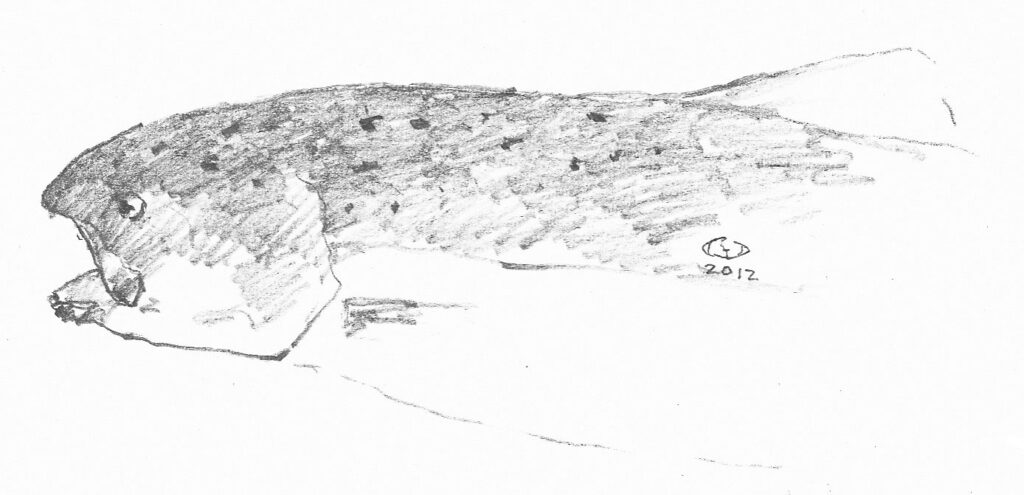

Far down in the bottom of the canyon, in a small tributary of Dry Creek that eventually finds its way to the Russian River at Healdsburg, a few wild steelhead fight their way up to an impassable falls, spawn, and then flee these headwaters, leaving their progeny in the hands of fate. This happens in January or February, and the young, born in March or April, must somehow survive until the rains of December release them on their journey to the sea.

Some miles to the west of here, over several high ridges, lie the headwaters of the Gualala, perhaps the North Coast’s most beautiful river. My family fished it starting back in the 1920s, and I cast my first line in it when I was fourteen, in 1954. As I sit writing this, my heart aches for the losses we have incurred through greed, stupidity, and ennui. The Gualala’s great run of silver salmon was relegated to extinction by one of the most vicious episodes of irresponsible clear-cut logging on the coast. Its steelhead, too, were brought to their knees through a 90 percent loss in numbers.

The exquisite Gualala notwithstanding, the epicenter of my relationship with the natural world through the acts of angling for silver salmon and steelhead was Tomales Bay and the watershed that flows into the head of it, that of Papermill Creek.

The Russian River was the most important river of my youth, but it lay sixty miles to the north of where I lived, a two-hour drive on the narrow, winding roads before freeways and in the simple, old-fashioned cars of the day. From my father’s driveway in San Anselmo, I could be parking my 1947 Plymouth at Papermill’s estuary in just under twenty minutes.

Although today the silvers are virtually gone and unlikely to ever return, due to unchecked piracy by factory ships throughout territorial waters off the entire coast of North America, rather than due to logging, as was the case up at the Gualala, in those bygone times, tens of thousands of them pushed up through Tomales Bay, crowding finally into the tidal part of the creek to await the first rains of the season, which would send them thrashing upstream to the spawning beds.

This happened starting about the end of October, and as a rule, by the middle of December, they were gone from the tidewaters and had distributed themselves throughout the system in the main stem Papermill and its tributaries, from the junction of Nicasio Creek to the base of Carson Dam, and throughout Lagunitas Creek, from Shafter’s Falls clear up to Woodacre. They populated the entirety of Olema Creek, as well. Prior to their departure, it was not unusual for me to have caught and let go many hundreds at a time when the admonition “Catch and release” would not be coined until at least 20 years later.

The stage was now set for the arrival of the steelhead: curtains closed, footlights dimmed, the hall filled with the anticipatory scratchings of the orchestra tuning up. But once in a while, there was a surprise, such as the one I got on November 9, 1958. I know this date because I wrote it on the rod that evening. It was a converted six-foot spinning rod I had just made, for which I had constructed a 22-foot shooting head I thought would be a perfect tool for the Salmon Hole, and it was. Starting at dawn, about halfway through the falling tide, lasting until dead low at about 11, I caught seven silvers, none of which I killed. It was a soft, bright, clear, windless day, and there were five other people fishing the hole. Three of these, including the game warden Al Giddings, were bait fishing from the steep bank across from me, while the other two threw spoons with spinning outfits from the beach on my side.

The tide had reached complete stillness, and I prepared to head home. It was such a sublime, almost warm midday, however, I decided to sit on the shore for a while, soaking it in and listening to the idle, if not goofy banter of the other fishermen. One of the spin guys had caught a nice eight-pound hen salmon, and throughout the tide, from across the creek, Al periodically reminded him that gentlemen shared their eggs.

Soon the tide began its slow flow upstream, and within fifteen minutes was moving pretty good. We never fished the incoming tide, at least I never had, but I thought why not try just for the hell of it—you’re here. So I positioned myself at the extreme bottom end of the pool, not wanting to pick up the lines of the bait fishermen. I had perhaps a thirty-foot window to work through before I got to them, and I did it slowly and methodically.

Just at the point where I dared not go any farther and where my fly was swinging through the low end of the tenderloin, the line tightened, and within seconds, a bright, silver fish was high in the air, two, three, four times, taking line at will and picking up all three bait outfits on its spectacular trip upstream through the hole.

The bait guys were all polite—you’d better be, in such close local quarters—and two of their lines miraculously cleared, while the third went for the rest of the ride. Finally, a chrome-bright 13-pound buck steelhead was nose to the gravel bar. I dispatched it with a stout piece of driftwood to the hurrahs of all present. My day had come to an unexpectedly dramatic conclusion, and I literally floated back across the field to the car, the great fish’s tail dragging in the grass.

Later that same season, the rains that allowed all the salmon to reach the spawning grounds subsided in the third week of December, and Papermill dropped, turning crystal clear. It was a perfect time for rough counting and observing close up and in detail the salmon’s yearly ritual, something I did for many years anytime water height and clarity permitted.

A few days before Christmas, I checked all the known holes from the Highway 1 Bridge at Point Reyes Station, down to White House Pool, through Giacomini’s field, to Railroad Point and Bivalve, where the creek becomes the bay, and I never saw a fish roll, nor did I get so much as a sniff. I was both surprised and disappointed.

Three days after Christmas, I was in my little room at home above the garage, tying some flies, when I heard my mother call out that the phone was for me. It was Bill, a high school friend I’d fished and duck hunted with for the past few years. “Guess what?” he said. “I just caught a 14-pound steelhead in the bay at the steps.”

“The steps? What the hell were you doing at the steps?”

“I went down there just because—I don’t know why—and as I was walking up the beach, a fish showed. I thought it was a striper, so I ran back up to the car and grabbed my outfit. It was rigged with a Flatfish, and I didn’t want to take the time to change, so I just started casting where I’d seen the fish, and within 10 minutes I had it on, and when I got it up to the beach, it was a steelhead.”

“The steps” was our name for a popular fishing spot along the bay for bait fishing for stripers. Someone had taken the trouble years earlier to dig out steps in the steep sixty or seventy-foot bank from the highway to the beach below. It passed through a tunnel in the windswept bay laurels. He said as the tide dropped, he saw a few other fish moving and hooked another, but lost it. As far as I knew, no one had ever thought of fishing for steelhead in this place. But there had to be a reason why those steps were carved into the hillside. I figured it was striper-related and must have something to do with the configuration of the bottom. Naturally, I would be there the next day, but my friend couldn’t, because he’d just gotten a job and had to go to it.

In late December and early January, this part of the coast experiences some of the most radical tides of the year. Highs can be 7.0 or even slightly higher, while the low can be as much as minus 1.6, creating a drop of eight and a half feet, and this was the cycle we were in. I checked the tide book and saw that low at the Golden Gate was at 2:30 in the afternoon. Adjusting for the delay north to the mouth of Tomales Bay of 20 minutes and then to the head of the bay of another hour and a half, that put the minus low at about 4:30. At this time of year, it was dark by six. I was there at 2:30.

Hanging in the area where my friend had caught his fish, I made a few desultory casts and scanned the water for any movement. The wind was blowing from the north at a very manageable 15 knots, and this allowed me to see that the current was becoming confined to the channel directly in front of me, which was about 60 feet wide. Beyond it to the west, looking at Inverness and stretching north toward Millerton Point, an increasing sheen told me the mud flats were about to become exposed.

Then, 300 yards away to the northwest, I saw something I couldn’t identify at first, some sort of splashing commotion. As I watched, it kept up until, as it drew closer, its rhythmic, violent writhing became a fish zigging and zagging across the flat, its back out of water, a rooster tail of spray behind it. When it reached the channel, a mere 100 feet below me, it vanished from sight.

Almost immediately, two more such apparitions appeared in the distance, which turned into two more fish desperately seeking the safety of the channel. Upon seeing that first fish, my mind instinctively said “striper.” As these next two approached, however, the water they were negotiating was only about four inches deep, and I could make out that they were unquestionably steelhead.

Oh, man, I thought, I’ve got at least three fish in front of me somewhere in an area smaller than a tennis court. I didn’t know precisely how deep the channel was, but based on what was then only several years’ experience with the bay, I guessed between two and three feet, at most. I was using an eight-foot fiberglass rod of dubious heritage, but what mattered was the line, a beautiful brown-and-black version of Sunset’s half-and-half line, a woven combination of Dacron and nylon designed to sink slowly in estuarine environments. In today’s terms, the outfit would probably be designated an 8. With it, I could work my fly around in a slow swing, presumably midway between the surface and the bottom. My wonderful friend Gene Thompson, founder and proprietor of the Western Sport Shop in San Rafael, had presented it to me a few months earlier. It was a most welcomed gift, because I had precious little tackle in those days, namely, one rod, one reel, and one line, altogether having cost just under fourteen dollars. My regular straight Dacron line would have sunk far too fast to fish this water.

I started in with easy 60-foot casts quartering downstream, the 27-foot head ideally suited to the task at hand. After only five or six casts and an equal number of steps downstream, there was a deliberate stop, and when I swept the rod horizontally back, as was my custom, there was an instantaneous boil and subsequent thrashing that told me the channel was even shallower than I thought, two feet deep, at the most.

It was not a difficult fight, because there were neither depth nor snags to deal with, only back and forth. Still, it was a spanking-fresh 10-pound steelhead, and while I was dealing with it, three or four more came wiggling desperately across the nearly dry flat, all of them reaching the channel.

I was using a simple fly with a red chenille body and white hair wing over it with no name, and I twisted it out of the left corner of that beautiful steelhead’s mouth and turned the fish around so it could shimmy back into the bay.

Collecting myself, I checked the leader for knots or nicks and toward the now-dry flat across from me fired another cast. It had swung only about 10 feet when it tightened and pointed right at a serious boil. This fish, too, had the expected resolve, and while I worked to get it in for a quick release, more fish could be seen fighting their way to the channel, only farther downstream, because the flat nearby was dry.

When the afternoon’s episode was said and done, I had hooked 14 fish, landed 12 of them, and saw at least 30 others enter the channel. And who knew now that darkness had fallen what the night would bring?

The following day, I arrived again at 2:30, even though the tide was an hour later. Knowing what I did, I started blind casting over what was clearly a depression—a hole, if you will—in the channel. Literally within five minutes, a fish was on, and this one took yard after yard of line in long screeches from the reel, obliging me to jog down the shore after it.

It never jumped, and it took a good 20 minutes for me to nose it up to the beach. I didn’t carry a scale or tape, and although I’ve never been a very good guesser, called it 12 pounds. Unlike all the others, which were chrome, this hen had begun to turn pink at the gills and along its lateral line, and this quality shone like mother-of-pearl in the afternoon sun.

I went back to casting, but nothing happened for the next two hours. Conditions were similar to those of the previous day, clear sky, north wind, and when the sheen over the flat began to appear, that’s when I saw the first two fish pushing across it in the familiar zigzag pattern of yesterday, and a few hundred yards behind them were several more. They disappeared into the channel 100 feet below me as before, and I eased down to greet them.

At the time, I fished every single day without exception, but never had I been in a situation where I knew beyond any shadow of a doubt that the next cast, or at the most the next two or three, would put me tight to a steelhead. It took just one, and I was holding a living rod. During the ensuing struggle, more fish were finding the channel.

I moved up the bank about 30 feet, thinking to show the fly to somebody in a calm resting mode who hadn’t been spooked by the antics of its schoolmate. One cast did it again, and the dance was repeated. To make a not very long story even shorter, I put the twelfth fish on, on the twelfth cast, and by the time it was dark, I had landed nine of them. When I fumbled my way up to the car, the Plymouth’s battery was dead. If I’d had a sledgehammer, I would have reduced it to scrap metal, but instead, I called it every single obscene name I could think of and then, exhausted, waited for a car to come by, which took at least half an hour. When headlights finally came around the corner, I put out my thumb, and the driver eased to a stop. It was an old man who didn’t have any jumper cables, so I rode with him into Point Reyes Station, where everything was closed up tighter than a frog’s behind, and that’s watertight.

In those days, hitchhiking was a viable means of transportation. The old man lived in town, so I walked to the Highway 1 Bridge, where the road from Inverness joins it, to wait for a car. The first one was going to Bolinas, so I had them drop me at the Olema corner. Within 20 minutes, along came an early 1950s Ford pickup driven by some sort of cowboy with a saddle in the bed, and he was going to Fairfax. As long as he was stopped, he rolled a cigarette, and then we rumbled off.

Every so often, his headlights flickered, and he had to shift down to make it over the Olema hill. Going down the other side, from my perspective, we were speeding, and I wondered if this guy knew the Tocaloma Bridge lay at a sharp angle to this long, downward straightaway, and also if his brakes were in better shape than his headlights. Soon, he started pumping them like mad, which caused the truck to shudder, but it slowed enough to negotiate the bridge.

Somewhere around San Geronimo or Woodacre, he slowed way down and with his elbows on the wheel, rolled and lit another smoke. Soon we were on the downside of White Hill, Fairfax not far off, when the headlights went out.

“Jesus,” I cried out, “What th. . .” and I thought, “That’s it, I won’t live long enough to vote.”

The cowboy said nothing and made no move to hit the brakes. Sheer blackness enveloped what I was certain was a careening coffin. The only light was the glow of his cigarette. In reality, the headlights were off for three, maybe four, seconds. A lifetime to me by the way, and then they flicked back on, and we were hardly over the center line. My heart was thumping around 200 beats a minute.

“Knew they would,” he said.

He was going only to Fairfax, but I asked if he could run me a few blocks farther and let me off at Smilin’ Ed Wood’s gas station right where Butterfield Road met Sir Francis Drake Boulevard.

“Sure, Sonny, glad to.”

As we pulled up, I fished around in my pocket for some change unsuccessfully. I didn’t even have a dollar bill.

“You couldn’t spare me a dime so I could call my mom, could you?” “Heck yeah, here ya go. Nice riding with ya.”

The next day, I outlined my plan to my mother. She drove a 1950 Chevrolet, and what we would do, I said, was get her dressed up warmly, then drive out to the bay with Dad’s jumper cables. We’d get the Plymouth started, then I’d drive a few miles up and down the road to charge the battery, then after that, I’d help her down the steps so she could witness the best steelhead fishing in the world.

Now, my mother never once touched a piece of fishing tackle or a firearm, nor did she ever express the slightest interest in doing so. As a girl, she’d had polio, so one leg was shorter than the other. Her idea of a walk was getting 20 feet from the kitchen to the garage. But here we were, pulled up in front of the Plymouth, which started, and after the charging ritual, I laboriously guided her bit by bit down the steps. She was bundled up in a good warm coat of mine, and we found a nice place for her to sit back by the cliff. It wasn’t such a nice day, with fog spilling over Inverness Ridge, bringing with it a very cold wind right in our faces. Undaunted, I began casting, even though the tide was still too high. Within 15 minutes, I miraculously had one on and wrangled it to the beach.

Looking over, I saw my mother huddled there like a little girl with a pained look on her face. Unhooking the fish, I carried it over to show her.

“That’s nice dear, but I really want to go home.”

I ran back and turned the fish loose, then laboriously helped her up the steps. It took 20 minutes. She pulled out onto the road, and I kept the jumper cables just in case. Back down on the beach, conditions were not pretty, and I was colder than my mother thought she was. The tide, now yet another hour later than yesterday, had a ways to go before it fell off the flat. In my youth, it took a lot to daunt me, so I cast relentlessly into the teeth of what was now rather a gale. The optimism of youth was rewarded by several grabs, which held.

I have always been fascinated by the phenomenon of fog spilling over a ridge, Inverness being my favorite of all, and I watched the beauty of it unfold. Then something inexplicable happened. Rays of light began flashing upward from the fog. The lights were very bright, with a slight yellowish cast, and then the voices started. At the time, I had never heard any of the great Masses, such as Bach’s in C Minor, but now, having heard them all, it was like that, only deafeningly louder, like a thousand voices. I became terrified, shaking, dropped the rod, and ducked my head and held my arms around myself. It grew louder and louder until it seemed to be everywhere. And the lights arched upward, too bright to look at. I suppose it lasted no more than five minutes before it began to subside and become just fog spilling over the ridge again.

I stood there for a while, trembling from more than the cold, wondering what it was that just happened. Fishing forgotten, I hurried up the steps to the car and sat there for a while, dumbfounded. When I finally calmed down, fortunately, the car started.

Clearly, the tide that had yielded such extraordinary fishing would now happen well after dark tomorrow. However, one of the characteristics of these big tides is that the interim one is much smaller. The next day, then, while the big minus would occur at 8:30 the previous night, the high of perhaps 5.0 would be at 2:30, and the low of 2.0 at 8:30 in the morning.

I had to wonder where all those fish went. Physically, they could get to the Highway 1 Bridge and somewhat beyond it, putting them out of reach. But given the low water, were they in that much of a rush? I needed to find out.

At dawn, I was pulling off at Bivalve, about a mile and a half upstream from the steps. The fog had somehow vanished, the sky was clear, the air dead calm. Here, the creek estuary became defined, and it turned sharply against the old railroad levee. An oysterman’s house, long abandoned, stood there on stilts. From the first minute I saw it, right after my sixteenth birthday, I wanted it to be my home.

I was on familiar ground now, having plumbed every part of the creek in the off-season from here to White House Pool in my eight-foot boat using a weight with a line attached to it. I knew right where the channel was and that on this mean low tide it was four feet deep.

Loving my new line for its perfect sink rate, I started at the top of the hole. Where they would be lying, if they were lying here at all, would be in a groove about 20 feet wide and a 150 feet long. The current was almost imperceptible, but enough to keep them facing into it.

After only a few casts, I was trying to hold my own with one of the brethren from a few days earlier. A beautiful buck, it was soon back in its element, confused, but safe. About an hour and a half later, six others had a peculiar experience to consider, as well.

Knowing the tide would soon be coming in, I wanted to prolong the experiment, so I scrambled up the bank, jumped in the car, and raced around toward White House Pool.

Approaching the Highway 1 Bridge, I slowed and glanced downstream, where I could see figures on the bank about 300 yards away. I knew the stretch they were fishing, a fairly deep, straight slot near where Olema Creek emptied into the slough. Several hundred yards after making the turn, I pulled off. There had been dense willows on both sides of the creek here, and a couple of the old-timers from Point Reyes Station fished it using a rowboat, completely safe from any bank fisherman. The summer before, though, all the trees were cleared, and now this great holding pool was naked for all to fish. The creek was only about 30 wide here, and after walking to the edge, I clearly recognized Giddings and two others from Inverness. In politically correct terms, they were African American fishing, which is not what it was called in the racist vernacular of the day. I knew Al’s penchant for using weightless roe, a deadly effective way to catch steelhead. The skeins of roe were preserved in Borax to toughen the outer skin, something we all did. In bigger, moving waters, the eggs were wrapped in netting to create “berries,” but Al eschewed this, preferring instead to use a unique snell on an Eagle Claw bait hook to hold the roe in place. For quiet water, this was just the thing. The previous winter, in late February, right under the bridge, he caught a spent fish that weighed 18 pounds, which would have put it over 20 had it been fresh.

The three of them were seated, rods propped in forked sticks. A silver fish was lying on the grass nearby.

“Hi Al,” I waved.

“C’mon over. There’s plenty of room. There’s a few in here, not many, and they’re not really biting, but maybe the fly could stir ’em up.”

“No, I’m checking out a few spots, but so far nothing. I’m going down to White House and if there’s nothing there, maybe I’ll come back around.” No sooner were the words out of my mouth and I thought, you dumb shit, what if there’s a pile of fish there. Then, when you don’t come back, Al and company will be on you like white on rice.

Jumping the fence past the No Trespassing sign, I waded over to the east bank below the end of the pool, positioning myself just upstream from the lowest holding water. Here, the incoming tide would be stalled for at least an hour. Within 10 minutes, a slow head-and-tail roll quickened my pulse, and to myself I uttered, “Saw you!” The line Gene had given me was so perfectly designed that the snap of my wrist straightened it out like a stretched string, the fly landing at the end of a fully extended leader, important in these close quarters, where inches could spell the difference between a wild ride and a complete skunking. My standard count in these four-foot deep waters was to 10 before starting the retrieve, but at seven, the line shot forward in a rare take on the sink, and I was involved in one of the most aerial ballets of my young life.

Fortunately, most of it took place fairly close to the steep bank by the road, where the few passing motorists couldn’t see it, and when one did go by, I released tension, pointing the rod straight at the fish, pretending to retrieve. Not wanting any visuals at all, when I thought it was ready, I knelt down in about a foot of water and hand-lined its head right up my thighs into the crotch of my Ball-Band waders, twisted the fly out and turned it around.

Just as I was getting ready to resume casting, a car pulled off the road up near the culvert, and a guy got out and started slowly toward me. Even at some distance, I recognized him and could see his dark Italian eyes searching the water. Please boys, I said to myself, no rolling just now, it wouldn’t be healthy.

Paul had graduated from Drake High two years ahead of me. The first time I ever hit the creek, he was there. And ever after that he was always there. He had a light spinning outfit and never used anything but a red-and-white Dardevle. He never stopped casting and knew every single place where the silvers might hold. He was one of the greatest fish hawks I ever saw. What he knew about steelhead I wasn’t sure, but it figured he knew plenty. Throwing fish back was not part of his DNA. and in fact, I was pretty sure that to him, the three-fish limit was merely a suggestion. He rarely spoke, preferring the nod as a greeting, but we maintained an affable, albeit distant relationship for many years. I thought it wise to commence casting, lest he think something was up. I cast perfectly, because to do otherwise would have aroused his suspicion. However, I retrieved the fly right away, so that it was only a couple of inches down, where it would be impossible to get a take. Ten minutes passed, and he stood still as a heron. It was a war of wills. The air was dead calm, and there was little traffic. All I could think was don’t roll, don’t roll. “Anything?” he finally said in a calm, conversational voice.

I chose my words carefully. “Nothing. They should be here by now, but maybe they’re a little late this year. Tried down below, but didn’t do any good.”

He didn’t say anything, but stood there in silence, then gave a cursory wave and started back. Right then there was another slow head-dorsal-tail roll, and I clearly saw the fish’s eye. The roll was soft and noiseless, and the minor disturbance was completely gone by the time Paul reached his car.

About 18 years later, I began spending winters in Marin County, doing so from 1976 through 1983. During this time, I rented a great studio in San Anselmo for 50 dollars a month and kept it year-round, not wanting to lose it. It was on the second floor of what had been the old Home Market, but which had recently been converted to shops. In the back was a small, soulful Italian restaurant called Riccardo’s, and I made good use of it.

Even though it was right downtown, it was one of those overlooked spaces that was off the radar and still cheap. My room was well-lit and had a balcony that overlooked the street. Right behind me, the cartoonist B. Kliban had a studio, too. His formal first name was Bernard, but he much preferred the nickname Hap, and we became good friends. In my view, he was the smartest, wittiest, and most original artist ever in his chosen genre. One day he said to me with a straight face, “I’d better come out with a new book pretty soon, or Gary Larson will starve.” Amen.

In his room he had literally thousands of drawings. I visited him every day, and he’d push a stack of them toward me. I’d look at them until my sides hurt so much from laughing, I had to retreat to my own, completely unfunny work. “You think these are funny?” He’d ask. And I couldn’t even get my breath enough to answer.

For about six months in 1979, I worked on a painting of Tomales Bay that was about five by six feet. Understandably enough, it would be titled Tomales Bay, and as it turned out, I think it was the best thing I’d ever done up until that time.

Hap visited my room, too, saying he longed to do what I did. One day he came by, watched me for a while, and said, “I’d like to know what it feels like to do that.” I handed him the brush and said, “Have at it. I’ll go sit by the window and read for a while.”

After about 10 minutes, he laid the brush down and stood up. “This is way too much pressure” he said, and I laughed. But I was careful to leave in the section he did because it worked. Soon after I finished the piece, Margot Kidder came up from Los Angeles to visit me. Flush from her recent role as Lois Lane in the first Superman film, she bought the painting, and it was shipped to her home in Bel Air.

Also, during that time I had developed a keen interest in cooking and soon discovered Frank Petrini’s market in Greenbrae. Its most stunning feature was the meat, poultry, fish, and shellfish counter, which looked to be 100 feet long, with dozens of butchers servicing customers as well as cutting meat in a large prep area.

On my first visit, there was Paul, working the seafood end of the counter. I greeted him like a long-lost friend, which in a sense he was, and asked if he was still hitting the creek, as he had in those early years.

“They’re not there. The salmon are gone. I try and I try and there’s nothing. A few steelhead, but as you know, that’s always been a crap shoot. But how could the salmon have all disappeared? There were so many.” His eyes were nearly black and had a certain sadness in them, his demeanor one of defeat, and as the light struck them, they were tearing up. As time passed, I saw him in this sort of casual way with some frequency for maybe 10 years, learning he never married and had no living family. Each time it was the same. “I’m sorry Paul, but they are really gone. The stripers, too.” He was a very simple person, and the creek had been it for him, and now it was a graveyard. To add injury to insult, some arrogant imbecile had convinced Fish and Game to close the creek to all fishing, as if that could do anything other than remove all who cared from the water, thereby neutering everyone who might spark some true inquiry. Under a false cloak of protectionism, society had reduced involvement to a badly produced television program.

For the next 20 years, my life was focused on developing my work in Montana, and I had the good fortune to circumnavigate the globe two dozen times in search of wild places. My heart, however, always belonged to the waters of my youth. In about the year 2000, I needed to spend some time in the Bay Area and in Marin. I had rented a house on Tomales Bay and headed to Petrini’s, which newly bore the name Molly Stone’s. It had now been truly transformed into a rich person’s store, filled with every wet dream you could imagine, complete with appropriate sticker shock.

The meat and seafood counter was still there, now proclaiming organic this and that, but no Paul. When one of the men asked if he could help me, I said I was wondering if Paul was there.

“Paul who?”

“Paul Mancini. He’s worked here for years.”

“Let me go ask Dino, he’s been around for quite a while.” “Thank you.”

Dino was a stout Italian who had to practically stand on his toes to see over the counter.

“You a friend of Paul’s?”

“Yes sir. We went to the same high school and fished together a lot when we were young.”

“I’m sorry. He passed away two years ago.” And he gave an abbreviated sign of the cross and disappeared from view.

Soon after Paul’s car was gone, I hooked a fish, landed it, and about 15 minutes later caught one more, and by the time I freed it, the tide had turned and was slowly creeping upstream. That was it for the day, because the flood and high ebb were difficult for a couple of reasons. First of all was the disorientation factor, and that plus the sheer volume of water made the whole thing problematic. That’s why I always had my paints in the trunk, and I would spend the rest of the day in a different mode, rendering cows on hillsides and lovely sloughs reflecting the sky. A little salami and bread was a nice thing, too.

As always, the next day, the tide was an hour later, low water at Bivalve about 9:30, give or take. The barometer was holding steady, skies clear, winds going to be manageable. It was just getting to fishing light when I pulled into the turnout above the oysterman’s house. I planned to make a pass through the slot, but my real target was Railroad Point, three-quarters of a mile upstream. I half expected to see Paul’s car and would have hidden mine, but there were no options in that regard. Besides, you couldn’t hide at Bivalve—anyone could watch you from two high vantage points.

It was still two hours until dead low tide, so the water had more movement than the day before. Starting at the top, I wondered if it was enough to prevent the half-and-half from delivering the fly to the very point of the steelheads’ noses. My answer came in the form of the most extraordinary take I’d ever experienced. As a rule in this kind of fishing, you get a stop, and after you set the hook is when the mayhem starts, whatever it turns out to be. In this case, however, one minute I was slowly retrieving the fly, the next the line was snapped from between my fingers and was zinging through the guides until it hit the reel. It was like a wide receiver catching a pass on the 50-yard line and then continuing on at top speed into the end zone. I have never wanted a drag on a fly reel, still don’t, believing if you can’t manage to control things with your fingers, you deserve the backlash you’re going to get. But I didn’t want my fingers anywhere near that spool at this particular moment, and by this time, the steelhead had out 200 feet of line and was down below the oysterman’s shack, making one of the highest, longest jumps I’d ever seen and breaking the leader. As a rule, broken leaders are the result of carelessness, but in this case, I cut myself some slack.

It was still early, but I was concerned that Paul, or someone else, for that matter, would arrive with the idea of checking out Railroad Point. Thinking that the atomic submarine I’d just hooked could have easily done a spook job on the groove, I decided to make just one pass through it. Right above the shack, I hooked and landed about an eight-pound hen and right below it hooked and lost another I never saw.

Reeling in quickly, I jogged over to the railroad levee, waded across the narrow gap where a short trestle had been, and walked to the hole, looking back every so often to see if another car may have parked on the bluff. None did. The sun was up, wind calm, an absolutely beautiful day. From the levee, I could look into the ideal green water with visibility of about 18 inches. Perfect.

This was one of the most interesting pools in the creek, and, along with the Salmon Hole in the middle of Giacomini’s field, the deepest. The silvers loved it, and for there to be 1,000 of them in it was routine. It basically had two holding areas in the shape of an L. Coming out of the field, one channel went straight to the bay, but it was shallow and false. The real one turned sharply east, forming a deep cut bank on its western edge. Then it ran straight into the railroad levee, creating a deep hole about 150 feet long running north, straight back toward the corner at Bivalve.

I figured if there were steelhead holding here, they’d be in the larger, deeper, lower part, but I’d keep my eyes and ears open for any signs in the upper option. With clear water, a nearly imperceptible current, no wind, and a bright sun overhead, I lengthened the leader to about 12 feet and put on a very slim sparse number six black fly.

One of the unpleasant difficulties of fishing this spot straight downstream, which is what I felt was the only viable way, was that you had to walk out on a sloping mud bank into which you sunk about twelve inches. There was a real danger of getting stuck and also of falling down, both of which I had experienced. In fact, the first time I ever fished there, I dubbed it “Goop’s Pool.”

The trick I learned was to take a stout stick with you for a third leg, as it were, and I had the perfect thing stashed behind the levee where the tide couldn’t reach it. It was about half an old oyster stake, and as I slogged my way into position, I brought it along, planting it behind me when I reached my casting position right at the water’s edge. I didn’t want to have to move to land a fish, and whatever happened this morning in this hole was going to happen without my moving my feet until I was ready to leave.

I figured the bucket here was 20 feet wide and about 80 feet long from where I stood, and at its deepest point was eight feet. There wasn’t much variation you could achieve in casting—11 to 1 o’clock was about it. For the hell of it, I split the difference on the first cast and decided on a 20 count.

As I began to move the fly, there was an odd sensation on the line, and I knew what it was. It had brushed across a fish’s back, and feeling it, the fish had moved off. I kept striping slowly until the line pulled tight and I had one. There were no histrionics, just a good solid tug of war. The sun was warm on my back, and as it penetrated the water, I could see the fish diving and thrusting. I had positioned myself appropriately for the landing and release, but after that spent some time extracting my boots from the mud, using my staff for support. I would stay put, because there was no point in doing otherwise. But I loosened my booted feet up some, not wanting to sink in any deeper than I already had. On the next few casts, the line rubbed fish every time, and on the fifth or sixth, it came up tight, and the head shake told me it was fair, not foul-hooked. After that, even though the line was touching them every time, it took 10 minutes to get another grab, which pulled out after 10 or 15 seconds.

Being obliged to remain stationary is a bit of a tough situation, because fish are so tuned to their environment. They may be fooled a few times, but they soon learn to fear and/or ignore all things suspicious. For instance, you can be out on the Gulf Stream in a school of dolphin fish, chumming them into a frenzy, then flipping them a fly. You’ll hook three or four, and pretty soon they’re still rushing at the phony, but veering off at the last minute. Or on an Atlantic salmon river in Russia, where you know there are 30 or 40 holding in a tailout, you’ll catch two, maybe three, change flies, catch two more, and that’s it. Same for a big pool on the Umpqua with dozens of visible steelhead in it. Up on Steamboat Creek one time, I sat watching a dense school of about 200 steelhead hanging in a crystal-clear pool with little current, their fins scarcely moving. I flipped in a pebble, and three fish rushed it, one of which ate it. A few minutes later, I flipped in another, and only one fish broke ranks to grab it and immediately spit it out. After that, pebble after pebble was completely ignored, other than a few aborted false rushes.

So this is rather where I was on this sublime early January day at my favorite fishing place on earth. My deities, the steelhead, were grouped before me, patiently awaiting a falling barometer and the subsequent deluge that would drive them to their spawning gravels, but for the time being, they were killing time at the train station, trying to ignore a panhandler.

The tide would soon turn, and I was stuck in the mud. Time to regroup, I thought. Using my staff, I managed to extract myself until I was back on higher ground, where I heard a serious whoosh. Looking over at the upper bank, rings were dissipating. So, bastards, lying up there too, eh?

I guessed I had maybe a half an hour before the flood started. At mean low tide I knew I could wade across the top of the hole. Bill and I had done it many times duck hunting. Even with a very slow current, casting across was difficult in terms of presentation to fish holding tight to the bank. To reach the roller, I had only to wade halfway across, then fire a cast downstream, let it sink, then work it back.

Minutes into it, the line tightened and a fish was in the air. No one was there to appreciate my grin, but the satisfaction was very sweet. It was a buck of maybe 10 pounds. Then the tide started rolling in, and I was back to my paints.

The next day, the neap low was at about 10 o’clock. Arriving at 7:30, I thought, why not check out the steps, which I did. It was quiet as a tomb, grebes and diving ducks going about their business, but not a fish in sight. No one would ever suspect the drama of only a few days ago. Not just the fishing, either. I looked up at the beautiful ridge, which was now just a ridge.

What was it that happened on that darkening afternoon? Maybe nothing, maybe I only imagined it. But I had never so much as tasted a drop of liquor at that age, and drugs were unheard of. Some enormous force in the universe had addressed me, that seemed certain. Was it a warning, meant to frighten me off? That didn’t seem right, because it was an exaltation, as if honoring heaven and earth. Now, some 50-odd years later, as the eleventh-hour fast approaches, I have come to suspect a very different motive. As Bach famously said, “Be content with your fate, as it is the only road to happiness there is.” Could that have been what was being revealed to me? Not by Bach, of course, but by the Supreme Spirit, which gave him and everything else to us, as well? Was it being foretold that throughout my journey I would sometimes minimize my calling, becoming distracted by the fool’s gold temptations of society, and that my unimpressive fishing stuff and fragile wooden sketch box, along with the pure love of using these, were the hand I was dealt and in the most real and deepest sense would be all I’d ever have? Some power beyond comprehension has protected me my whole life, and I can still see that light and hear those voices, so as long as I am granted the gift of breath, I will somehow try to reimburse the universe.

With the barometer still holding steady, my idea was to hit the Salmon Hole in the middle of Giacomini’s field. A profound holding area for silvers, it was also a sanctuary for steelhead in low-water conditions. I had a good place to hide my very recognizable car. It was a little road just west of Inverness Park. When I got out to the water, a spin guy from Inverness was already there. He wasn’t a very good fisherman, but his body took up space, and his dialog was inane. As I’d hoped, his lack of action propelled him back across the field, leaving me alone at the best hole on the creek.

The saga, if one may call it that, began at White House Pool. The popular fishing area was from there upstream to the Highway 1 Bridge. It was pretty much a story of people parking and fishing right by their cars, folding chairs being a common accoutrement. It was duffers and families mostly, drowning bait or else casting lures of one sort or another. I’d fished this reach of water with my dad and others since 1950, but not once with positive results. Then, days after my sixteenth birthday, I had headed out there in a very used car with better tackle and a new sense of curiosity and determination. Below White House Pool, the creek veered away from the road, stretching off into a meadow. I’d heard the land belonged to Giacomini and that he didn’t want people trespassing on it. I’d never seen a soul fishing down there, but overwhelmed by the youthful magnet of the unknown and little fear of chastisement, I climbed the fence.

About three-quarters of a mile into my investigation, the creek turned somewhat, revealing a beach on its west side, and on it a man was flycasting. I didn’t want to crowd him, but I had to get within about 100 feet to be in what I could identify as a nice hole literally boiling with salmon. I was using my Heddon nine-foot two-handed bamboo casting rod and Pflueger Supreme reel to throw a silver Flatfish and within 10 minutes was tight to a fish that I landed and dispatched with a length of driftwood.

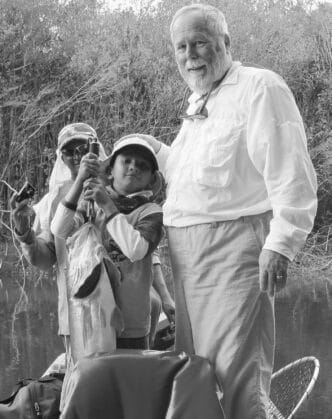

Reeling in, the man walked over to me, a large and confident presence. “That’s a nice one,” he said. “Al Giddings.” And he offered his hand. “Thanks, I’m Russ Chatham.”

“It’s a hen,” he went on, “You gonna use the roe?”

“Probably not,” I said. “I’ve bait-and-lure fished for years, but I’m trying to learn fly fishing, like you. It’s just that I don’t really have enough confidence yet.”

“Can I have it, then?”

The sinking sun glinted off his badge, and I realized he was the game warden. “I can’t seem to get a hit today.”

“Sure, I guess so.” And he knelt down and with his pen knife opened the 10-pound fish and carefully removed the two large skeins of eggs. “Steelhead’ll be coming in pretty soon, so thanks. You walk down from White House?

“Yeah.”

“Where do you live?”

“San Anselmo. But I’m out here almost every day.”

“We keep the rumor going that Giacomini doesn’t want anyone in here, even though he doesn’t care, because we like to keep this hole for the locals, but it’ll be okay if you want to park by the store over there and cross the field. It’s a hell of a lot shorter.”

In all the years I knew him, throughout hundreds of encounters, Al never asked to see my license. And when he did routinely check them at Papermill, if someone had forgotten to buy one, he never wrote a citation; instead, he simply asked them to run into town and pick one up at the Palace Market.

When I was arrested in 1959 by a new rookie warden for fishing after hours for stripers at the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge, I called Al and told him what had happened.

“Did you have fish in the boat?” “No.”

“Typical of you, then. I’ve never seen anybody throw back more fish than you. I could never write you a ticket.”

About two weeks after meeting Al that first time, I was at the Salmon Hole again, only this time with my fly rod. Al was there, along with one other man, spin fishing. Neither Al nor I could get a bite. On the other hand, it seemed like the lure guy was hooked up constantly. He landed one, two, and three, whapped them, and laid them up in the grass. He had his limit.

But then he walked back to the water and kept fishing. Soon, he hooked another, landed it, whapped it, and laid it up with the others. Al reeled in and walked over to me. In a low voice he said, “You saw what just happened?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Well, there are 10, maybe 15,000 salmon holding between the bridge and Millerton Point. The lumber mill south of Olema closed this year, and this guy was one of many who were laid off. He has four kids and needs those fish to feed his family, so I’d appreciate it if you just pretend you didn’t see anything.” In my view, Al was the truest of wardens, on the lookout for serious offenders, like jacklighters, salmon giggers, or those who took 10 times the limit of striped bass to sell on the black market.

Some cloud cover was developing, and I sensed a change in the weather. But now it was calm. It’s a straight shot from White House Pool to the Salmon Hole. Then there comes a bend and thus a groove on the far side five or six feet deep. The bend continues and then hits a steep mud bank, and the depth increases to eight feet at low tide.

Some ruddy ducks and mud hens were noodling around, but otherwise it was quiet.

I worked through the hole without a touch until I was at the low end, where I’d caught that fluke steelhead on the incoming tide. Looking downstream perhaps 150 yards, I saw motion in the water. Often it’s just a bird, but since there was nothing where I was, I climbed out and crossed the inside channel that made the Salmon Hole beach an island. Paul knew about the lower slot, and I was well aware of its holding capacity, with a depth of six feet. You could fish it from the east side, because the bottom was firm, but I was on the high bank to the west. I’d see him down there often, because he liked to be away from other fishermen. I never went down there when he was fishing, not wanting to crowd him.

Once he caught a 20-pound silver, and it’s the only time I ever heard him cry out. Miraculously, he got his hand in its gills and heaved it up onto the bank. He waved me down, and when I got there, he was just kneeling, looking at it. Neither of us said anything, and then he picked it up and headed back to the road.

I sat down, figuring just to watch for five or 10 minutes, because there was a grebe working the hole, and that could easily have been what I saw. The grebe wasn’t too fond of me and paddled away downstream. I had become a bird watcher, not my dream as a fisherman, when right before my eyes there was a slow head-dorsal-tail roll about 50 feet below me.

Without any need to move or even stand up, I draped a cast over it and began the count and then the retrieve. I guess I could have predicted the take, although I am rarely that confident. To land it, I had to slide off the bank and would have gone in over my head, were it not for a last-minute handful of pickleweed. The eight-pound hen dashed away healthily. Climbing back up, I surveyed my domain. Minutes passed with nothing of any interest happening. Then I saw the wakes. The transition from where I was to the Salmon Hole was a flat about two feet deep. It had a hard bottom, which is where you crossed to fish the lower slot from the inside of the bend. I lost no time heading back upstream to the pool itself.

Because there was no one else there, I could position myself wherever I wanted, so I chose the heart of the hole, right where Al Giddings would be standing, if he were there. In the nearly imperceptible current, I felt confident that the depths could be probed thoroughly and effectively. Three or four casts into it, I was tight to a surging presence, and 10 minutes later released a hen back into the system.

Twenty feet upstream, there was a roller, and I walked quickly above it and in one cast had it on. As I released it, another fish showed in the upper slot, and I jogged up above it, too. It took two casts until I was fast to it. Working upstream, I could see wakes deliberately heading for White House Pool. I worked back and forth through the hole, but nothing else happened until the tide started in.

That night, my father’s barometer was falling, and sometime after midnight, the rain started. I got up anyway and headed out, deciding to try a nice little groove about 200 feet below the Highway 1 Bridge. It made sense, in my mind. Somehow, I knew no one would be there, because it seemed the creek had vanished from most people’s consciousness once the salmon were gone.

As I applied my beautiful half-and-half line over this precious water, I thought of Gene and how grateful I was for his gift. I would tell him about all this, of course, and he would puff on his cigar and not say much, probably figuring I’d made most of it up.

As the rain pounded down, dripping off my hood, I kept my composure and my 10 count until the line came alive, and I was there in that most beautiful of places, my querencia, and I waltzed with my steelhead until it lay on the beach. I never kill without an apology, so when I slammed the driftwood over the hen’s head, I was kneeling and asking for forgiveness. I would give the eggs to Al. By nightfall, all the steelhead would be safely miles upstream.