The wind stirred the collar of my jacket and blew my fly line sideways across the lake’s surface. The sun was nearly down, and it was getting positively chilly, even though the day had been fair. Along the far shore, house lights were coming on, and a fair portion of the homes were already burning Christmas lights, even though the holiday was still weeks away. My friends and I had fished all day, hoping for not just a keepersized bass, but one of those really big fish known to inhabit this modest Southern California water-supply impoundment.

It wasn’t a lake I normally fish, but having been invited by one of the homeowners, and knowing that last spring it produced two largemouths each weighing well over the 10-pound mark, I didn’t want to pass up the opportunity to fish here.

Actually, if truth were told, I didn’t expect much action, and today had lived up to my expectations. Fishing for trophy-sized bass during winter is mostly a losing proposition.

Surface temperatures were in the mid-50-degree range around midday, and a cool northwest wind had ruffled the lake all day. There were three of us, all fairly good warmwater anglers, and between us, we’d scored exactly two bass, one of two pounds, the other a tad larger, but nowhere near the three-pound mark.

At full dusk, we finally quit. The wind was getting stronger, and air temperatures were going down rapidly. Oh, it wasn’t like ice fishing, or even a winter afternoon on the Owens River in December or January, but it was certainly cold, and the wind made it even colder. So why were we there? Here’s why: we were following the trout-stocking truck. Big largemouth bass key on freshly planted trout and come to the party almost as if they had a printed stocking schedule from the Department of Fish and Game. This small city lake gets a couple of truckloads of hatchery rainbow trout each year so the local residents have something to fish for through the winter months, and there’s nothing that a really big grandma bass likes more than a belly full of dim-witted hatchery rainbows that

haven’t had the time to get used to their new, wilder surroundings (by the way, the biggest largemouths will almost always be females). The cooling water reduces the food requirements for warmwater species, but it doesn’t stop them from eating entirely, and the bigger that the bass are in spots like this, the more eagerly they receive the hatchery trout.

Years ago, I used to work with a guy who had fallen hard for conventional tackle bass angling. He had bought a bass boat, several thousand dollars worth of fancy tackle, and was putting in many weekends a year on the local pro tour. During a lunchtime bragging session, late in the winter, he told of being at one of the smaller San Diego City lakes when the state truck arrived with a load of hatchery trout.

“You should have seen the huge bass that loomed up out of the water around the launch ramp,” he said, spreading his hands to indicate monster-sized bass. “They knew when the stocking truck was coming, and they’d come up out of deep water and just wait for the trout. If you were lucky, you could catch them by throwing a big swimbait.”

One of my favorite memories of big fish coming out the depths to feed on hatchery-raised trout is of a night at Silverwood Lake some years ago. A number of us arrived a couple of hours after a late-afternoon trout plant. Silverwood’s wide launch ramp and nearby marina docks were the location for a feeding spree you often hear about, but seldom see. A bunch of the regulars were already there. These were men who delighted in fishing for big bass and bigger stripers whenever and wherever they could be found. They had a communications underground that worked better than the CIA for ferreting out the latest hot spot, and this week, Silverwood had been turning out both huge stripers and some very large largemouths.

Standard equipment was a surf-casting rod capable of throwing up to 20pound test monofilament and a facsimile rainbow trout made from soft plastic (a swimbait) that was hefty enough to attract the really big predators. I was the only one that evening equipped with a fly rod, but several of the big-fish hunters around me were also competent fly anglers. I’d fished with a couple of them in the Sierra, but they considered a fly rod and fly-rod-sized fish simply a diversion, not “real” fishing.

There are some real differences between what the conventional-tackle angler can offer the prey he or she is after and what the average fly rod and fly pattern will — or can — do. First, you can’t toss any kind of fly, with any kind of fly rod, as far as a burly surf caster can throw a leadhead swimbait, although I’ve yet to see anybody working a stocking event with a Spey rod.

You also can’t cast a fly that comes anywhere near the size of a freshly stocked rainbow trout that may be anywhere from 9 inches in length to 12 inches, or at least, you can’t cast it well. You can try, but by the time you upscale everything from hook to hackle to create a fly that’s 8 or 9 inches long, you’ve created a monster that sounds ominous when is whistles by your head, and should you fluff a cast and smack yourself in the noggin with the fly, you’ll remember it.

So no, you can’t compete with the big-lure boys and girls, but you can offer a large streamer fly and see if anything snaps it up in passing. This works sometimes, although not nearly as often as you would like. That evening, I was equipped with a 9-weight rod that will throw a fast-sinking line a decent distance, even in my clumsy hands, and with a handful of feather-and-marabou streamers that showed a fairly large silhouette to a passing fish. Their color was mostly white, with a bit of red Flashabou running down the sides and some dark peacock herl to give a suggestion of green on the back.

I fished from the shore for a while, then — ignoring the signs that stated “No Fishing from Dock” (there was no park ranger around) — I walked out on the courtesy dock on the right side of the ramp. There was still some light to the west, but the sky was growing darker, making it difficult to observe what was happening on the water. However, you didn’t really have to see. Except for the cables that hold the docks in place, there’s nothing in your way except water that is at least 30 feet deep midway out on the docks. You didn’t have to see the action, either. You could hear it.

Most of the day’s stocked trout were milling around at the waterline on the ramp. Perhaps they felt comforted by the concrete they were used to. Every so often, there would be a sound like somebody falling in the lake, and another trout would become food for a bigger fish.

Several stripers weighing as much as 20 pounds had been caught in the melee. A couple had been kept, but in general, these fishermen were already into catch-and-release angling, preferring to spend precious minutes restoring their fish to decent condition before letting them go. It’s easy with a fish that fits into your hand, but try it with something as long as your leg sometime.

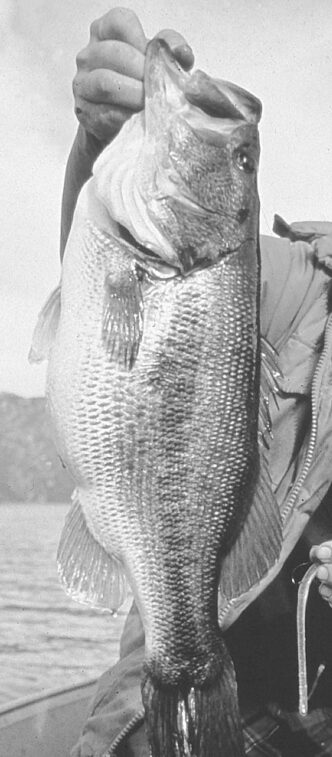

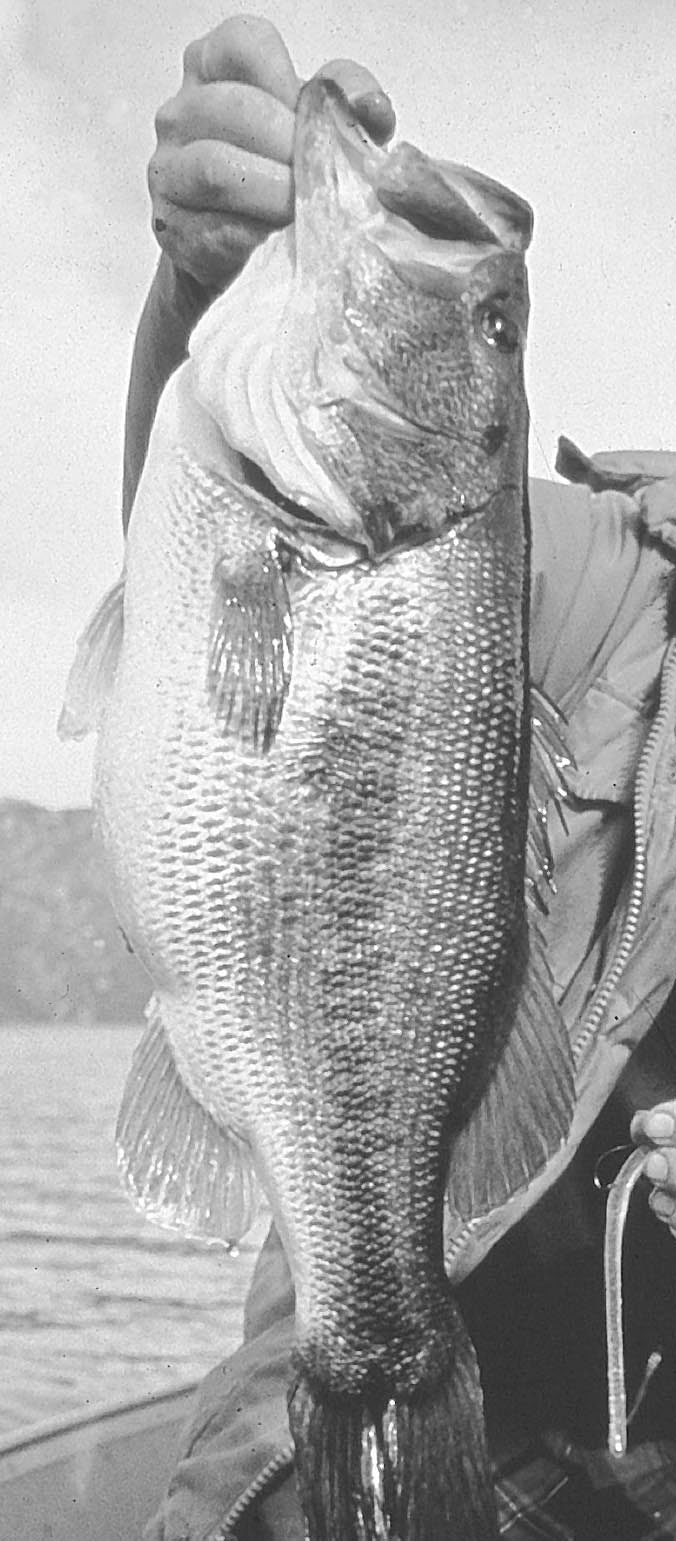

On cast number 40, or perhaps 50, something smacked my streamer, and I set the hook hard. The fish shook its head a couple of times, then headed for the cable on the opposite dock. It made two or three runs toward the cable that would allow it to wrap the leader around the steel wire and break me off, but turned away each time. In a couple of minutes, I got my first look at the fish. It was a largemouth bass big enough not to be prey for the striped bass and also big enough to consider a hatchery trout a snack.

When I got my hands on it, I lifted the fish out of the water with a grunt. The guy just inboard of me on the dock grabbed his scale, and we did a quick weigh-in in the fading light — just a hair over seven pounds. I slipped the bass back into the lake and just stood there for perhaps a minute, elated with the catch, but wanting to take in the sights and sounds. It was then that I remembered I had a small 35-millimeter camera in a case on my belt. Oh well.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that if trophy-sized striped bass and largemouths find a trout plant an attractive dining opportunity, then the fly angler hoping to put a monster-sized mount in his or her den should pay attention to when and where trout plants occur.

For the Southern California lakes that I fish, the beginning of the troutplanting season is usually the end of October, or no later than the middle of November. This weekly stocking ritual will persist all winter until perhaps the end of March, when surface temperatures begin to warm enough to switch back to stocking catfish for the summer. The various lakes that feature winter-season trout fishing might use only DFG fish, or they might contract with a private fish farmer to receive extra trout to stock. Over the years, I’ve even seen fast-growing triploid trout from both private and government sources and exotic cross-bred fish with unusual colors and sizes.

Your local newspaper will usually have stocking reports, even if they don’t do any other outdoor-sports reporting. If necessary, you can hit the DFG website, look up the stocking listings, and learn what’s going on out there.

The best plants are those made when the weather is crappy. A bit of drizzle, overcast skies, and a cold wind, while troubling to fish in, will likely enhance your rate of success. The ruffled surface of the water and the low light levels can give the bigger predators and their prey a sense of security, bringing them much closer to the top of the water column.

Equip yourself with a rod that meets the challenge. An 8-weight or 9-weight is good, and match that with a sinking line. I’ll leave the sink rate up to you, because I don’t know where you’ll be fishing.

Flies should be large, yet sleek enough that they aren’t too much of a hassle to cast. I favor patterns such as oversized versions of Lefty’s Deceiver and Bob Slamal’s White Fly. Except for the White Fly, I like prominent eyes on my streamers, and white is the basic color for this kind of fishing.

Be prepared to fish for wall-hanger bass or stripers as though you were fishing for steelhead. You may make a hundred casts before you get a fish. You may make several hundred casts and never get bitten. If suffering isn’t in your bag of fly-fishing tricks, chances are you might want to stay home and tie flies for spring.

You can fish in a crowd (which is generally what you get the day the trout are planted) or as a solitary figure the third day following the visit of the hatchery truck. Either way, you will be looked at as possibly a little crazy. That is, until you catch a bass big enough to put both your fists into its mouth. Or hook a striped bass as long as your leg.